Space stations and habitats in fiction

The concepts of space stations and habitats are common in modern culture. While space stations have become reality, there are as yet no true space habitats. Writers, filmmakers, and other artists have produced vivid renditions of the idea of a space station or habitat, and these iterations can be categorized by some of the basic scientific concepts from which they are derived.

Space stations

Space stations in science fiction can employ both existing and speculative technologies. One of the earliest images was the rotating wheel space station (such as the Stanford torus), the inertia and centripetal force of which would theoretically simulate the effects of gravity. Stations using artificial gravity are still purely speculative.

Space stations allow characters a relatively constrained setting, serving either as plot site or as safe refuge to which one can retreat. Since they are literary devices, there is no scientific imperative for their evolution to have followed the logical succession of scientific progress as it exists in reality; they may contain any artifact or device demanded by the plot, and can be provided by design or mere happenstance.

Space stations are often used as headquarters for organizations, which are thus linked to, but independent of, their place of formation, as research facilities in which experiments too dangerous for planetary settings can be carried out, and as the relics of lost civilizations, left behind when other things are removed.

Space stations rotating for pseudogravity

- The film (and novel) 2001: A Space Odyssey is set in part on Space Station V, built as an 1,836-foot (560 m) partially completed double ring, revolving to produce one-sixth gravity. This station model is one of the most familiar designs from science fiction films.

- Various stations in the 1996 Japanese anime Cowboy Bebop used torus space stations, although a number of the space colonies ignore physics and gravity laws behaving as Earth would. The ship Bebop itself also had an artificial gravity segment that slowly rotated as a cylinder inside of the fuselage, separate from the flight deck and hangar.

- The 2003 Japanese anime Planetes has one of its main sets in the ISPV-7 (Seven), the 7th orbital station around the Earth while the 9th is under construction by the year 2075. It depicts accurately the zero-gravity zone around the axis, the microgravity service ring and the 1-g gravity external ring. The elevators have g-force indicators and harnesses for the passengers. Handles and grips are ubiquitous out of the 1-g area. The space station ISPV-7 serves as the base for the recovery ship DS-12 "Toybox".

- Space Station One is the home of the Space Family Robinson. It is mobile, capable of planetary descent, and large enough for the family, with hydroponic gardens and two small shuttle crafts ("Spacemobiles"). Their ship functions as a habitat while attempting to return to earth.

- Venus Equilateral Relay Station, from the 1940s Venus Equilateral series by George O. Smith, is a communications hub set in Venus' L4 point.

- The 1979 James Bond film Moonraker features a space station used as a base to launch attacks on Earth.

- The television series Babylon 5 is set on a space station of that name in the years 2258–2262.

- One book of the Outlanders series is set on a station called Parallax Red, supposedly launched by the United States, located at one of the Lagrangian points.

- In the Command & Conquer series, the GDI faction has most of their command staff on a space station named Philadelphia.

- Mystery in Space and Strange Adventures, the two most popular science fiction comic books of the 1950s, often depicted wheel-shaped space stations on their covers and in their stories.

- In the Sonic the Hedgehog series, the Space Colony Ark is a near-Earth colonization ship, on which a secret research program has given birth to the Ultimate Lifeform, Shadow the Hedgehog.

Space stations using artificial gravity

- The Star Trek franchise features several space station designs that all use artificial gravity. UFP Deep Space Station K7, Earth Station McKinley, and the Federation Spacedocks are examples, as is Jupiter Station, a research and development facility, and Deep Space Nine (aka DS9 or Terok Nor), which most of the series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine is based upon.

- The Death Star and the Death Star II from the Star Wars series are mobile space stations designed to destroy entire planets. They are capable of travelling interstellar distances, and are the size of moons or small planets. Artificial gravity, not rotation, is used to counter weightlessness.

- In the space role-playing game EVE Online, most actions besides mining, travelling and combat take place in space stations orbiting moons and/or planets.

- Many episodes of Doctor Who take place on space stations, including StationFive / the Gamestation and Platform One, built five billion years in the future to witness Earth's destruction in the episode "The End of the World".

- The Disney movie Zenon: Girl of the 21st Century and its two sequels are set on a space station in the 2050s.

- In Stargate Atlantis, a "Stargate bridge" links the Milky Way and Pegasus galaxies. Because of differences between the Milky Way and Pegasus Stargates, there is a space station linking the two "gates" midway between the galaxies.

Other space stations

- The 1986 film SpaceCamp features a space station called "Daedalus". Its design is reminiscent of early proposals for Space Station Freedom.

Habitats

Spherical habitats

Dyson spheres

- A Dyson sphere constructed around the inner solar system is the distant future home of advanced humans and Morlocks in Stephen Baxter's novel The Time Ships, a sequel to H.G. Wells' The Time Machine.

- A Dyson sphere is encountered in "Relics", episode 4 of season 6 of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

Bernal spheres

The Bernal sphere is a rotating sphere housing tens of thousands of people.

- Space Colony ARK, a Bernal sphere colony in the Sonic the Hedgehog video games; in Sonic Adventure 2, it was incorrectly called a "Bernoulli sphere".

- Gagarin Station is a Bernal sphere colony in the Mass Effect video games.

- Oracle is a Bernal sphere colony ship in the MMORPG Phantasy Star Online 2 (2014); it is accompanied by its Arks escort colony ships.

- The terraria in Kim Stanley Robinson's novel 2312 are similar to a Bernal sphere, consisting of hollowed-out asteroids with attached motors. They are used for a variety of purposes, including residential, agricultural and conservational.

Toroidal or annular habitats

Tori

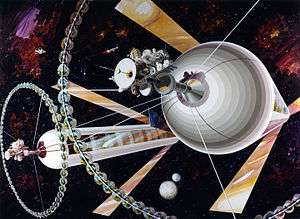

A rotating torus sometimes quite large in diameter makes possible extensive artificial worlds.

- One of the earliest portrayals of a torus station is shown in 1957 Soviet film Road to the Stars by Pavel Klushantsev.

- Earth-orbiting Space Station V invented by Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick and depicted in Kubrick's 1968 movie 2001: A Space Odyssey.

- The short film L5: First City in Space is set on a Stanford torus at L5.

- The novels of the Gaea Trilogy by John Varley are set on an unusual organic satellite of Saturn that is shaped as a Stanford Torus.

- In the anime series Mobile Suit Gundam Wing, most of the many space colonies in Earth orbit are based on the Stanford torus. The anime series Mobile Suit Gundam 00 also depicts Stanford tori-type space stations. The Laplace Residence in Gundam Unicorn is also an example of a Stanford torus.

- In the anime series Planetes, the main action also takes place in a Stanford torus-type space station around Earth.

- Hideo Kojima's PlayStation 2 video game Zone of the Enders is set aboard a Stanford torus-type space station orbiting Jupiter called Antillia Colony.

- The video game Startopia is set aboard a series of Stanford tori.

- The video game Mass Effect features the Citadel, resembling a small Stanford torus with multiple arms attached. Arcturus Station, the Alliance capital, is also a Stanford torus, although it is never seen in-game.

- Saturnalia and A Lion on Tharthee by Grant Callin features SpaceHome, a group of toroid space stations connected in a pinwheel fashion.

- James P. Hogan wrote several novels that included a Stanford torus, including The Two Faces of Tomorrow, Endgame Enigma, and Voyage From Yesteryear.

- FreeMarket Station, in the FreeMarket RPG, is a large Stanford Torus in stationary position near Saturn and home to over 85,000 transhuman individuals. Similar but smaller structures in this setting include Liberty (Earth L5) and Garuda (Mars).

- The titular space station in Elysium, the 2013 science fiction film written and directed by Neill Blomkamp, strongly resembles a Stanford torus. However, it has an open atmosphere which make it more akin to a Bishop Ring. The lack of enclosure allowed the immigrant shuttles to land on Elysium.

- The X game series has the planet encompassing Earth Torus which serves as a high orbital space dock for Terrans.

- In the 2004 Battlestar Galactica TV series there is often a ship within the fleet that resembles a Stanford torus with a long cylindrical center.

- In C. J. Cherryh's Alliance-Union universe most stations are described as rotating tori. The inside cover art for Downbelow Station shows the internal divisions of Pell station, a torus.

Bishop rings

The Bishop ring design is a ring 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) in radius and 500 kilometres (310 mi) thick, capable of supporting populations into the tens of billions. It requires mastery of carbon nanotubes.[1]

- Bishop Rings are a common type of habitat in the universe of the Orion's Arm world-building project, where the width of individual rings can vary from as little as 100 kilometres (62 mi) to as much as 500 kilometres (310 mi).

Other rings

- The titular 'Halos' of the Halo video game series.

- Orbitals from the Culture series by Iain M. Banks. Banks was engaged in the social implications of space colonisation, basing the politics of the Orbitals on his conclusion that the hostility and scale of space would be inherently demand socialism within an Orbital but anarchism in its interactions with other settlements.[2]

- The Ringworld from Larry Niven's Known Space universe.

Cylindrical habitats

O'Neill cylinders

O'Neill's Island Three design, commonly called an O'Neill cylinder, consists of a pair of counter-rotating cylinders, each 3.2 kilometres (2.0 mi) in radius and 32 kilometres (20 mi) long, housing a population of up to 10 million.

- In the SF-artwork book Mechanismo: An Illustrated Manual of Science Fiction Hardware (1978), edited by Harry Harrison, an illustration of Island Three is shown with technical notes.

- Jerry Pournelle and John F. Carr edited an anthology of SF stories set in O'Neill cylinders or other types of space colonies, published in 1979 as The Endless Frontier volumes 1 and 2.

- In the various Gundam anime series, O'Neill cylinders are common – especially in the Universal Century, where nine billion human beings live in these colonies. The Gundam series space colony design is usually portrayed with a rotational speed much faster than the original O'Neill design. This is in part for visual effect. All Gundam series involve space, and most are about conflicts between Earth and humans living in space colonies.

- Vonda McIntyre's Starfarers series of novels is set on the Starfarer, a classic O'Neill double-cylinder space colony adapted to make faster-than-light interstellar jumps.

- Alexis A. Gilliland's Rosinante novels feature a "dragon scale mosaic mirror", consisting of a large number of small mobile mirrors mounted on a cone around each habitat. These provide illumination, generate power, and defend the habitat. The array is much larger than the mirrors of O'Neill's design, but does not rotate with the habitat and so does not need as much structural strength.

- An O'Neill cylinder similar to those found in the Gundam series provides the setting for a stage in the game Tekken 5. The arena consists of a glass platform mounted near the axis at one end of the habitat, with the rotating cylinder providing the backdrop. The stage is called "The Final Frontier", and the exterior can be seen in a cutscene. The view through the window would suggest that the facility is much nearer to the earth than the typical scenario. The same cylinder is also featured in Tekken 6, in a stage called "Fallen Colony", where the habitat has crashed down to Earth.

- Hideo Kojima's adventure game Policenauts takes place in an O'Neill space colony located at the L5 Lagrange Point. These structures can also be seen in shooting games like Axelay (stage 2), Zone of the Enders, Super Earth Defense Force (stage 4), R-Type Final (stage 1), Thunder Force IV (Ruin stage), GG Aleste (stage 1), and Vanquish.

- The Neyel, a race in the Star Trek novel The Sundered (by Andy Mangels and Michael A. Martin), were originally Earth humans who lived on Vanguard, an O'Neill-type habitat constructed inside an asteroid. (The name 'Neyel' is itself derived from O'Neill.)

- The conclusion of Interstellar reveals that an O'Neill Cylinder has been built above Earth, with Earth's population migrating to it.

- The Galactic Whirlpool, a Star Trek novel written by David Gerrold, focused on an O'Neill-style space station that had been retro-fitted as a generational interstellar ship.

- Gene Wolfe's series The Book of the Long Sun take place on a generation ship, essentially a massive O'Neill cylinder, where the inhabitants have long forgotten that they are on a ship or journey. The series is followed by The Book of the Short Sun and is also linked to Wolfe's master work, The Book of the New Sun.

- In the Italian comic book Nathan Never, Earth has spawned a number of space colonies in the form of O'Neill cylinders.

- The anime series Sora wo Kakeru Shojo features an Island Three type space colony controlled by a narcissistic AI named Leopard as a major character.

- David J. Williams' The Burning Skies features an O'Neill cylinder attacked by terrorists.

- The miniseries L5 (2012) features an abandoned O'Neill cylinder.

- In the Warhammer 40K books, it is mentioned that before Mankind mastered artificial gravity and Warp travel, "Ohnyl Cylinders" were used as habitats and generation ships.

McKendree cylinders

The McKendree cylinder design is a scaled-up O'Neill cylinder with a radius of 460 kilometres (290 mi) and a length of 4,600 kilometres (2,900 mi), capable of supporting populations in excess of 100 billion. This design requires mastery of carbon nanotubes.[3]

- McKendree cylinders are a type of habitat in the universe of the Orion's Arm world-building project, but scaled up to the theoretical limits of carbon nanotubes: 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) in radius and 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi) long, containing 63 million square kilometres (24 million square miles) of living space—greater than the continent of Eurasia.

Other cylinders

- Robert A. Heinlein, in his 1963 novelisation Orphans of the Sky (compiling two stories published in 1941), introduced revolving cylinders to emulate gravity. In this case there were many concentric levels, at which gravity stepwise-decreased towards the centre of the structure, resulting in zero gravity at the very centre.

- In the Rama series of books by Arthur C. Clarke, gigantic alien spacecraft similar to O'Neill cylinders are explored by astronauts. Perhaps due to its design for interstellar travel, Rama lacks the mirrors and windows of an O'Neill cylinder, but does have lights arranged in three strips along its length, paralleling the placement of the windows. Note that Rendezvous with Rama was published (1973) in the period between O'Neill running the classes in which his cylinder design was produced and his publication, therefore the designs are likely entirely independent.

- The television series Babylon 5 concerned an O'Neill-style space station 8.0 kilometres (5 miles) long. While the single cylinder Babylon 5 did not feature a counter-rotating section, its predecessor Babylon 4 did. Like Rama, Babylon 5 lacks the mirrors and windows of an O'Neill cylinder, but does have a fixed central light source. Day and night are simulated as the landscape below revolves around the light source.

- In Ken Macleod's Learning the World, the 'Sunliner' Slow interstellar travel vessel But the Sky, My Lady! the Sky!, is based around an O'Neil cylinder with a central artificial 'sunline' (a miniature star strung out like an oversized tubular fluorescent bulb) that is simply activated and deactivated on a 24‑hour cycle, rather than relying on windows. On either end is a 'cone' together containing a bridge, maintenance systems, spare reaction fuel and propulsion/power grid systems.

- Peter F. Hamilton's The Night's Dawn trilogy makes several references to an O'Neill halo orbiting Earth. The books aren't specific, but imply that it is constituted of a multitude of asteroids orbiting Earth. Also the Edenist culture of the books are said to inhabit huge Habitats that are slight variation on the O'Neill cylinder, though they are a gigantic living being. These habitats have a central light tube running through the centre of the structure rather than the mirror panels proposed in the original design. His Commonwealth Saga books also describe the character Ozzie Isaacs' home, which is an O'Neill cylinder located within an asteroid.

- Orson Scott Card's novel Ender's Game concerns mostly the events taking place on Battle School, a short O'Neill cylinder, which houses the all-important Battle Room in the center of its rotation, which keeps it at null gravity.

- The Citadel space station in the video game Mass Effect resembles an O'Neill cylinder, although there are no windows and atmosphere is only kept to around seven metres. The "land" sections are made up mostly of large buildings reminiscent of a city. Its head section is a Stanford torus, housing the headquarters of political and strategic decision-making. A second station, "Jump Zero", is mentioned but not yet seen in the franchise, and is described as a Bernal Sphere.

- The French writer Bernard Werber in his novel Le papillon des étoiles described a generation ship under the form of a long rotating cylinder with central lightning tube. This ship is described to be privately constructed.

- The 2001 novel Chasm City by Alastair Reynolds features a spindle-shaped variant, with higher gravity at the center and low gravity at the points. This is mentioned to be cheaper to build than cylindrical colonies.