Spencer repeating rifle

| Spencer Repeating Rifle | |

|---|---|

|

Spencer repeating Rifle | |

| Type | Manually cocked Lever Action Rifle |

| Place of origin |

|

| Service history | |

| Used by |

United States Army United States Navy Confederate States of America Japan Empire of Brazil |

| Wars |

American Civil War Indian Wars Boshin War Paraguayan War Franco-Prussian War |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Christopher Spencer |

| Designed | 1860 |

| Manufacturer | Spencer company, Burnside Rifle Co,[1] Winchester |

| Produced | 1860–1869 |

| Number built | 200,000 approx. |

| Specifications | |

| Length |

47 inches (1,200 mm) rifle with 30 inch barrel 39.25 inches (997 mm) carbine with 22 inch barrel[2] |

| Barrel length |

30 inches (760 mm) 22 inches (560 mm)[3] 20 inches (510 mm)[4] |

|

| |

| Cartridge | .56-56 Spencer rimfire |

| Caliber | .52 inches (13 mm) |

| Action | Manually cocked hammer, lever action |

| Rate of fire | 14 or 20 rounds per minute[5] |

| Muzzle velocity | 931 to 1,033 ft/s (284 to 315 m/s) |

| Effective firing range | 500 yards[6] |

| Feed system | 7 round tube magazine |

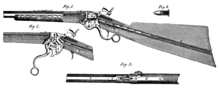

The Spencer repeating rifle was a manually operated lever-action, seven shot repeating rifle produced in the United States by three manufacturers between 1860 and 1869. Designed by Christopher Spencer, it was fed with cartridges from a tube magazine in the rifle's buttstock.

The Spencer repeating rifle was adopted by the Union Army, especially by the cavalry, during the American Civil War, but did not replace the standard issue muzzle-loading rifled muskets in use at the time. The Spencer carbine was a shorter and lighter version.

Overview

The design for a magazine-fed, lever-operated rifle chambered for the .56-56 Spencer rimfire cartridge was completed by Christopher Spencer in 1860. Called the Spencer Repeating Rifle, it was fired by cocking a lever to extract a used case and feed a new cartridge from a tube in the buttstock. Like most firearms of the time, the hammer had to be manually cocked in a separate action before the weapon could be fired. The weapon used copper rimfire cartridges based on the 1854 Smith & Wesson patent stored in a seven-round tube magazine. A spring in the tube enabled the rounds to be fired one after another. When empty, the spring had to be released and removed before dropping in fresh cartridges, then replaced before resuming firing. Rounds could be loaded individually or from a device called the Blakeslee Cartridge Box, which contained up to thirteen (also six and ten) tubes with seven cartridges each, which could be emptied into the magazine tube in the buttstock.[7]

Unlike later cartridge designations, the .56-56 Spencer's first number referred to the diameter of the case just ahead of the rim, the second number the case diameter at the mouth; the actual bullet diameter was .52 inches. Cartridges were loaded with 45 grains (2.9 g) of black powder, and were also available as .56-52, .56-50, and a wildcat .56-46, a necked down version of the original .56-56. Cartridge length was limited by the action size to about 1.75 inches; later calibers used a smaller diameter, lighter bullet and larger powder charge to increase power and range over the original .56-56 cartridge, which was almost as powerful as the .58 caliber rifled musket of the time but underpowered by the standards of other early cartridges such as the .50–70 and .45-70.

History

At first, the view by the Department of War Ordnance Department was that soldiers would waste ammunition by firing too rapidly with repeating rifles, and thus denied a government contract for all such weapons. (They did, however, encourage the use of carbine breechloaders that loaded one shot at a time. Such carbines were shorter than a rifle and well suited for cavalry.)[8]More accurately, they feared that the armies logistics train would be unable to provide enough ammunition for the soldiers in the field, as they already had grave difficulty bringing up enough ammunition to sustain armies of tens of thousands of men over distances of hundreds of miles. A weapon able to fire several times as fast would require a vastly expanded logistics train and place great strain on the already overburdened railroads and tens of thousands of more mules, wagons, and wagon train guard detachments. The fact that several Springfield rifle-muskets could be purchased for the cost of a single Spencer carbine also influenced thinking.[9] However, just after the Battle of Gettysburg, Spencer was able to gain an audience with President Abraham Lincoln, who invited him to a shooting match and demonstration of the weapon on the lawn of the White House. Lincoln was impressed with the weapon, and ordered Gen. James Wolfe Ripley to adopt it for production, after which Ripley disobeyed him and stuck with the single-shot rifles.[1][10]

The Spencer repeating rifle was first adopted by the United States Navy, and subsequently adopted by the United States Army, and used during the American Civil War, where it was a popular weapon.[11] The Confederates occasionally captured some of these weapons and ammunition, but, as they were unable to manufacture the cartridges because of shortages of copper, their ability to take advantage of the weapons was limited.

Notable early instances of use included the Battle of Hoover's Gap (where Col. John T. Wilder's "Lightning Brigade" of mounted infantry effectively demonstrated the firepower of repeaters), and the Gettysburg Campaign, where two regiments of the Michigan Brigade (under Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer) carried them at the Battle of Hanover and at East Cavalry Field.[12] As the war progressed, Spencers were carried by a number of Union cavalry and mounted infantry regiments and provided the Union army with a firepower advantage over their Confederate adversaries. At the Battle of Nashville, 9,000 mounted infantrymen armed with the Spencer, under the command of Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson, chief of cavalry for the Military Division of the Mississippi, rode around Gen. Hood's left flank and attacked from the rear. President Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth was armed with a Spencer carbine at the time he was captured and killed.[13]

The Spencer showed itself to be very reliable under combat conditions, with a sustainable rate-of-fire in excess of 20 rounds per minute. Compared to standard muzzle-loaders, with a rate of fire of 2–3 rounds per minute, this represented a significant tactical advantage.[14] However, effective tactics had yet to be developed to take advantage of the higher rate of fire. Similarly, the supply chain was not equipped to carry the extra ammunition. Detractors would also complain that the amount of smoke produced was such that it was hard to see the enemy, unsurprising, since even the smoke produced by muzzleloaders would quickly blind whole regiments, and even divisions as if they were standing in thick fog, especially on still days.[15]

One of the advantages of the Spencer was that its ammunition was waterproof and hardy, and could stand the constant jostling of long storage on the march, such as Wilson's Raid. The story goes that every round of paper and linen Sharps ammunition carried in the supply wagons was found useless after long storage in supply wagons. Spencer ammunition had no such problem.[16]

In the late 1860s, the Spencer company was sold to the Fogerty Rifle Company and ultimately to Winchester.[17] Many Spencer carbines were later sold as surplus to France where they were used during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870.[18]

Even though the Spencer company went out of business in 1869, ammunition was manufactured in the United States into the 1920s. Later, many rifles and carbines were converted to centerfire, which could fire cartridges made from the centerfire .50-70 brass. Production ammunition can still be obtained on the specialty market.[19]

See also

- M1819 Hall rifle

- Cimarron Firearms

- Henry rifle

- Sharps rifle

- Volcanic rifle

- List of individual weapons of the U.S. Armed Forces

Notes

- 1 2 Walter, John (2006). The Rifle Story. Greenhill Books. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-85367-690-1.

- ↑ http://www.romanorifle.com/html/spencer.html

- ↑ The M-1863 version

- ↑ The M-1865 version

- ↑ Walter, John (2006). The Rifle Story. Greenhill Books. pp. 256, 70–71. ISBN 978-1-85367-690-1.

The fire-rate of the Spencer was usually reckoned as fourteen shots per minute. The Spencer rifle with a Blakeslee quickloader could easily fire twenty aimed shots a minute

- ↑ "The Spencer Repeater and other breechloading rifles of the Civil War". Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ "Blakeslee Cartridge Box". National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ↑ Philip Leigh "Lee's Lost Dispatch and Other Civil War Controversies" (Yardley, Penna.: Westholme Publishing, 2015), 25-36

- ↑ Davis, Burke (1982). The civil war: strange & fascinating facts (1st ed.). New York, NY: Fairfax Press. p. 135. ISBN 0517371510.

- ↑ Washington Times, February 2, 2016

- ↑ "Spencer Carbine". CivilWar@Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ↑ Rummel III, George, Cavalry of the Roads to Gettysburg: Kilpatrick at Hanover and Hunterstown, White Mane Publishing Company, 2000, ISBN 1-57249-174-4.

- ↑ Steers, Edward (12 September 2010). The Trial: The Assassination of President Lincoln and the Trial of the Conspirators. University Press of Kentucky. p. 93. ISBN 0-8131-2724-6.

- ↑ "The Spencer Repeater". aotc.net Army of the Cumberland. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ↑ "More on Spencer's Seven Shot Repeater". Hackman-Adams. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ↑ Pritchard, Russ A. (1 August 2003). Civil War Weapons and Equipment. Globe Pequot Press. pp. 49–41. ISBN 978-1-58574-493-0.

- ↑ Houze, Herb (28 February 2011). Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. pp. 69–70. ISBN 1-4402-2725-X.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer (21 November 2012). Almanac of American Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 1028. ISBN 978-1-59884-530-3.

- ↑ Flatnes, Oyvind (30 November 2013). From Musket to Metallic Cartridge: A Practical History of Black Powder Firearms. Crowood Press, Limited. p. 410. ISBN 978-1-84797-594-2.

Further reading

- Chris Kyle and William Doyle, "American Gun: A History of the U.S. in Ten Firearms".

- Earl J. Coates and Dean S. Thomas, An Introduction to Civil War Small Arms.

- Ian V. Hogg, Weapons of the Civil War.

- Barnes, Cartridges of the World.

- Philip Leigh Lee's Lost Dispatch and Other Civil War Controversies, (Yardley, Penna.:, Westholme Publishing, 2015), 214

- Marcot, Roy A. Spencer Repeating Firearms 1995.

- Sherman, William T. Memoirs Volume 2 - contains an account of the success of the Spencer on combat (pp. 187–8) and reflections on the role of the repeating rifle in warfare (pp. 394–5).

External links

- The patent drawing for the Spencer action

- Description and photos of Spencer rifle, serial number 3981

- Production information on the Spencer carbine

- The Spencer repeater and other breechloaders used in the Civil War