Red pulp

| Red pulp | |

|---|---|

Transverse section of a portion of the spleen. (Spleen pulp labeled at lower right.) | |

Spleen | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pulpa splenica |

| FMA | 15844 |

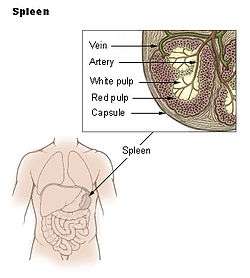

The red pulp of the spleen is composed of connective tissue known as the cords of Billroth and many splenic sinuses that are engorged with blood, giving it a red color.[1][2] Its primary function is to filter the blood of antigens, microorganisms, and defective or worn-out red blood cells.[3]

The spleen is made of red pulp and white pulp, separated by the marginal zone; 76-79% of a normal spleen is red pulp.[4] Unlike white pulp, which mainly contains lymphocytes such as T cells, red pulp is made up of several different types of blood cells, including platelets, granulocytes, red blood cells, and plasma.[1]

Sinusoids

The splenic sinuses of the spleen, also known as sinusoids, are wide vessels that drain into trabecular veins. Gaps in the endothelium lining the sinusoids mechanically filter blood cells as they enter the spleen. Worn-out or abnormal red cells attempting to squeeze through the narrow intercellular spaces become badly damaged, and are subsequently devoured by macrophages in the red pulp.[5] In addition to aged red blood cells, the sinusoids also filter out particles that could clutter up the bloodstream, such as nuclear remnants, platelets, or denatured hemoglobin.

Cells found in red pulp

Red pulp consists of a dense network of fine reticular fiber, continuous with those of the splenic trabeculae, to which are applied flat, branching cells. The meshes of the reticulum are filled with blood:

- White corpuscles are found to be in larger proportion than they are in ordinary blood.

- Large rounded cells, termed splenic cells, are also seen; these are capable of ameboid movement, and often contain pigment and red-blood corpuscles in their interior.

- The cells of the reticulum each possess a round or oval nucleus, and like the splenic cells, they may contain pigment granules in their cytoplasm; they do not stain deeply with carmine, and in this respect differ from the cells of the Malpighian corpuscles.

- In the young spleen, macrophages may also be found, each containing numerous nuclei or one compound nucleus.

- Nucleated red-blood corpuscles have also been found in the spleen of young animals.

Diseases

In lymphoid leukemia, the white pulp of the spleen hypertrophies and the red pulp shrinks.[4] In some cases the white pulp can swell to 50% of the total volume of the spleen.[6] In myeloid leukemia, the white pulp atrophies and the red pulp expands.[4]

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- 1 2 Luiz Carlos Junqueira and José Carneiro (2005). Basic histology: text & atlas. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 274–277. ISBN 0-07-144091-7.

- ↑ Michael Schuenke, Erik Schulte, Udo Schumacher, Lawrence M. Ross, Edward D. Lamperti (2006). Atlas of anatomy: neck and internal organs. Thieme. p. 219. ISBN 1-58890-360-5.

- ↑ Victor P. Eroschenko, Mariano S. H. di Fiore (2008). Di Fiore's atlas of histology with functional correlations. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 208. ISBN 0-7817-7057-2.

- 1 2 3 Carl Pochedly, Richard H. Sills, Allen D. Schwartz (1989). Disorders of the spleen: pathophysiology and management. Informa Health Care. pp. 7–15. ISBN 0-8247-7933-9.

- ↑ Cormack, David H. (2001). Essential histology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 169–170. ISBN 0-7817-1668-3.

- ↑ Jan Klein, Václav Hořejší (1997). Immunology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 30. ISBN 0-632-05468-9.

External links

- Anatomy Atlases - Microscopic Anatomy, plate 09.175 - "Spleen: Red Pulp"