Square root of 3

| Binary | 1.10111011011001111010… |

| Decimal | 1.7320508075688772935… |

| Hexadecimal | 1.BB67AE8584CAA73B… |

| Continued fraction | |

The square root of 3 is the positive real number that, when multiplied by itself, gives the number 3. It is more precisely called the principal square root of 3, to distinguish it from the negative number with the same property. It is denoted by

The square root of 3 is an irrational number. It is also known as Theodorus' constant, named after Theodorus of Cyrene, who proved its irrationality.

The first sixty digits of its decimal expansion are:

As of December 2013, its numerical value in decimal has been computed to at least ten billion digits.[1]

The fraction 97/56 (1.732142857…) for the square root of three can be used as an approximation. Despite having a denominator of only 56, it differs from the correct value by less than 1/10,000 (approximately 9.2×10−5). The rounded value of 1.732 is correct to within 0.01% of the actual value. The traditional mnemonic device for remembering this rounded value is George Washington's year of birth, 1732.

Archimedes reported (1351/780)2

> 3 > (265/153)2

,[2] accurate to 1/608400 (six decimal places) and 2/23409 (four decimal places), respectively.

It can be expressed as the continued fraction [1; 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, …] (sequence A040001 in the OEIS), expanded on the right.

It can also be expressed by generalized continued fractions such as

which is [1; 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, …] evaluated at every second term.

The following nested square expressions converge to :

Proof of irrationality

This irrationality proof for the square root of 3 uses Fermat's method of infinite descent:

Suppose that √3 is rational, and express it in lowest possible terms (i.e., as a fully reduced fraction) as m/n for natural numbers m and n.

Therefore, multiplying by 1 will give an equal expression:

where q is the largest integer smaller than √3. Note that both the numerator and the denominator have been multiplied by a number smaller than 1.

Through this, and by multiplying out both the numerator and the denominator, we get:

It follows that m can be replaced with √3n:

Then, √3 can also be replaced with m/n in the denominator:

The square of √3 can be replaced by 3. As m/n is multiplied by n, their product equals m:

Then √3 can be expressed in lower terms than m/n (since the first step reduced the sizes of both the numerator and the denominator, and subsequent steps did not change them) as 3n − mq/m − nq, which is a contradiction to the hypothesis that m/n was in lowest terms.[3]

An alternate proof of this is, assuming √3 = m/n with m/n being a fully reduced fraction:

Multiplying by n both terms, and then squaring both gives

Since the left side is divisible by 3, so is the right side, requiring that m be divisible by 3. Then, m can be expressed as 3k:

Therefore, dividing both terms by 3 gives:

Since the right side is divisible by 3, so is the left side and hence so is n. Thus, as both n and m are divisible by 3, they have a common factor and m/n is not a fully reduced fraction, contradicting the original premise.

Geometry and trigonometry

The square root of 3 can be found as the leg length of an equilateral triangle that encompasses a circle with a diameter of 1.

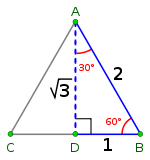

If an equilateral triangle with sides of length 1 is cut into two equal halves, by bisecting an internal angle across to make a right angle with one side, the right angle triangle's hypotenuse is length one and the sides are of length 1/2 and √3/2. From this the trigonometric function tangent of 60 degrees equals √3, and the sine of 60° and the cosine of 30° both equal √3/2.

The square root of 3 also appears in algebraic expressions for various other trigonometric constants, including[4] the sines of 3°, 12°, 15°, 21°, 24°, 33°, 39°, 48°, 51°, 57°, 66°, 69°, 75°, 78°, 84°, and 87°.

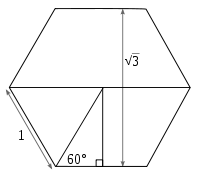

It is the distance between parallel sides of a regular hexagon with sides of length 1. On the complex plane, this distance is expressed as i√3 mentioned below.

It is the length of the space diagonal of a unit cube.

The vesica piscis has a major axis to minor axis ratio equal to 1:√3, this can be shown by constructing two equilateral triangles within it.

Square root of −3

Multiplication of √3 by the imaginary unit gives a square root of −3, an imaginary number. More exactly,

It is an Eisenstein integer. Namely, it is expressed as the difference between two non-real cubic roots of 1 (which are Eisenstein integers).

Other uses

Power engineering

In power engineering, the voltage between two phases in a three-phase system equals √3 times the line to neutral voltage. This is because any two phases are 120° apart, and two points on a circle 120 degrees apart are separated by √3 times the radius (see geometry examples above).

See also

Notes

- ↑ Lukasz Komsta. "Computations | Łukasz Komsta". komsta.net. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ↑ Knorr, Wilbur R. (1976), "Archimedes and the measurement of the circle: a new interpretation", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 15 (2): 115–140, doi:10.1007/bf00348496, JSTOR 41133444, MR 0497462.

- ↑ Grant, M.; Perella, M. (July 1999). "Descending to the irrational". Mathematical Gazette. 83 (497): 263–267. doi:10.2307/3619054.

- ↑ Julian D. A. Wiseman Sin and Cos in Surds

References

- S., D.; Jones, M. F. (1968). "22900D approximations to the square roots of the primes less than 100". Mathematics of Computation. 22 (101): 234–235. doi:10.2307/2004806. JSTOR 2004806.

- Uhler, H. S. (1951). "Approximations exceeding 1300 decimals for √3, 1/√3, sin(π/3) and distribution of digits in them". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 37 (7): 443–447. PMC 1063398

. PMID 16578382.

. PMID 16578382. - Wells, D. (1997). The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers (Revised ed.). London: Penguin Group. p. 23.

External links

- Theodorus' Constant at MathWorld

- Kevin Brown

- E. B. Davis