Larynx

| Larynx | |

|---|---|

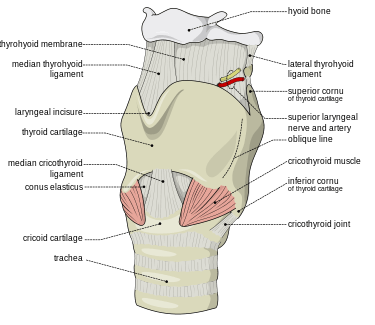

Anatomy of the larynx, anterolateral view | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | larynx[1] |

| Greek | λάρυγξ (lárynx)[1] |

| MeSH | D007830 |

| TA | A06.2.01.001 |

| FMA | 55097 |

The larynx /ˈlærɪŋks/ (plural larynges; from the Greek λάρυγξ lárynx),[1] commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the neck of tetrapods involved in breathing, sound production, and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. It manipulates pitch and volume. The larynx houses the vocal folds (vocal cords), which are essential for phonation. The vocal folds are situated just below where the tract of the pharynx splits into the trachea and the esophagus.

Structure

Cartilages

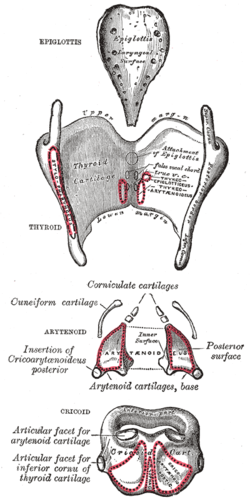

There are six cartilages, three unpaired and three paired, that support the mammalian larynx and form its skeleton.

Unpaired cartilages:

- Thyroid cartilage: This forms the Adam's apple. It is usually larger in males than in females. The thyrohyoid membrane is a ligament associated with the thyroid cartilage that connects the thyroid cartilage with the hyoid bone.

- Cricoid cartilage: A ring of hyaline cartilage that forms the inferior wall of the larynx. It is attached to the top of trachea. The median cricothyroid ligament connects the cricoid cartilage to the thyroid cartilage.

- Epiglottis: A large, spoon-shaped piece of elastic cartilage. During swallowing, the pharynx and larynx rise. Elevation of the pharynx widens it to receive food and drink; elevation of the larynx causes the epiglottis to move down and form a lid over the glottis, closing it off.

Paired cartilages:

- Arytenoid cartilages: Of the paired cartilages, the arytenoid cartilages are the most important because they influence the position and tension of the vocal folds. These are triangular pieces of mostly hyaline cartilage located at the posterosuperior border of the cricoid cartilage.

- Corniculate cartilages: Horn-shaped pieces of elastic cartilage located at the apex of each arytenoid cartilage.

- Cuneiform cartilages: Club-shaped pieces of elastic cartilage located anterior to the corniculate cartilages.

Muscles

The muscles of the larynx are divided into intrinsic and extrinsic muscles.

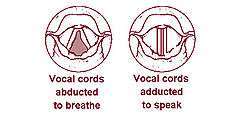

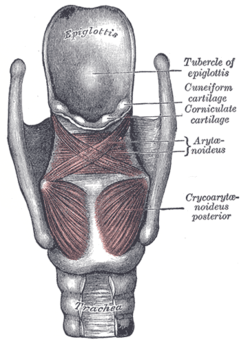

The intrinsic muscles are divided into respiratory and the phonatory muscles (the muscles of phonation). The respiratory muscles move the vocal cords apart and serve breathing. The phonatory muscles move the vocal cords together and serve the production of voice. The extrinsic, passing between the larynx and parts around; and intrinsic, confined entirely. The main respiratory muscles are the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles. The phonatory muscles are divided into adductors (lateral cricoarytenoid muscles, arytenoid muscles) and tensors (cricothyroid muscles, thyroarytenoid muscles).

Intrinsic

The intrinsic laryngeal muscles are responsible for controlling sound production.

- Cricothyroid muscle lengthen and tense the vocal folds.

- Posterior cricoarytenoid muscles abduct and externally rotate the arytenoid cartilages, resulting in abducted vocal folds.

- Lateral cricoarytenoid muscles adduct and internally rotate the arytenoid cartilages, increase medial compression.

- Transverse arytenoid muscle adduct the arytenoid cartilages, resulting in adducted vocal folds.[2]

- Oblique arytenoid muscles narrow the laryngeal inlet by constricting the distance between the arytenoid cartilages.

- Thyroarytenoid muscles - sphincter of vestibule, narrowing the laryngeal inlet, shortening the vocal folds, and lowering voice pitch. The internal thyroarytenoid is the portion of the thyroarytenoid that vibrates to produce sound.

Notably, the only muscle capable of separating the vocal cords for normal breathing is the posterior cricoarytenoid. If this muscle is incapacitated on both sides, the inability to pull the vocal folds apart (abduct) will cause difficulty breathing. Bilateral injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve would cause this condition. It is also worth noting that all muscles are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus except the cricothyroid muscle, which is innervated by the external laryngeal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (a branch of the vagus).

Additionally, intrinsic laryngeal muscles present a constitutive Ca2+-buffering profile that predicts their better ability to handle calcium changes in comparison to other muscles.[3] This profile is in agreement with their function as very fast muscles with a well-developed capacity for prolonged work. Studies suggests that mechanisms involved in the prompt sequestering of Ca2+ (sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-reuptake proteins, plasma membrane pumps, and cytosolic Ca2+-buffering proteins) are particularly elevated in laryngeal muscles, indicating their importance for the myofiber function and protection against disease, such as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.[4] Furthermore, differential levels of Orai1 in rat intrinsic laryngeal muscles and extraocular muscles over the limb muscle suggests a role for store operated calcium entry channels in those muscles functional properties and signaling mechanisms.

Extrinsic

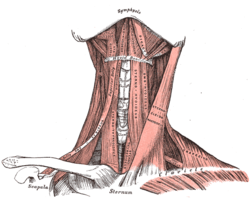

The extrinsic laryngeal muscles support and position the larynx within the trachea.

- Sternothyroid muscles depress the larynx.

- Omohyoid muscles depress the larynx.

- Sternohyoid muscles depress the larynx.

- Inferior constrictor muscles

- Thyrohyoid muscles elevates the larynx.

- Digastric elevates the larynx.

- Stylohyoid elevates the larynx.

- Mylohyoid elevates the larynx.

- Geniohyoid elevates the larynx.

- Hyoglossus elevates the larynx.

- Genioglossus elevates the larynx

Innervation

The larynx is innervated by branches of the vagus nerve on each side. Sensory innervation to the glottis and laryngeal vestibule is by the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve innervates the cricothyroid muscle. Motor innervation to all other muscles of the larynx and sensory innervation to the subglottis is by the recurrent laryngeal nerve. While the sensory input described above is (general) visceral sensation (diffuse, poorly localized), the vocal fold also receives general somatic sensory innervation (proprioceptive and touch) by the superior laryngeal nerve.

Injury to the external laryngeal nerve causes weakened phonation because the vocal folds cannot be tightened. Injury to one of the recurrent laryngeal nerves produces hoarseness, if both are damaged the voice may or may not be preserved, but breathing becomes difficult.

Development

In adult humans, the larynx is found in the anterior neck at the level of the C3–C6 vertebrae. It connects the inferior part of the pharynx (hypopharynx) with the trachea. The laryngeal skeleton consists of six cartilages: three single (epiglottic, thyroid and cricoid) and three paired (arytenoid, corniculate, and cuneiform). The hyoid bone is not part of the larynx, though the larynx is suspended from the hyoid. The larynx extends vertically from the tip of the epiglottis to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage. Its interior can be divided in supraglottis, glottis and subglottis.

In newborn infants, the larynx is initially at the level of the C2–C3 vertebrae, and is further forward and higher relative to its position in the adult body.[5] The larynx descends as the child grows.[6][7]

Function

Sound generation

Sound is generated in the larynx, and that is where pitch and volume are manipulated. The strength of expiration from the lungs also contributes to loudness.

Manipulation of the larynx is used to generate a source sound with a particular fundamental frequency, or pitch. This source sound is altered as it travels through the vocal tract, configured differently based on the position of the tongue, lips, mouth, and pharynx. The process of altering a source sound as it passes through the filter of the vocal tract creates the many different vowel and consonant sounds of the world's languages as well as tone, certain realizations of stress and other types of linguistic prosody. The larynx also has a similar function to the lungs in creating pressure differences required for sound production; a constricted larynx can be raised or lowered affecting the volume of the oral cavity as necessary in glottalic consonants.

The vocal folds can be held close together (by adducting the arytenoid cartilages) so that they vibrate (see phonation). The muscles attached to the arytenoid cartilages control the degree of opening. Vocal fold length and tension can be controlled by rocking the thyroid cartilage forward and backward on the cricoid cartilage (either directly by contracting the cricothyroids or indirectly by changing the vertical position of the larynx), by manipulating the tension of the muscles within the vocal folds, and by moving the arytenoids forward or backward. This causes the pitch produced during phonation to rise or fall. In most males the vocal folds are longer and with a greater mass than most females' vocal folds, producing a lower pitch.

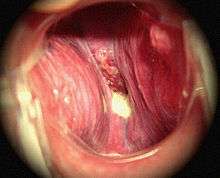

The vocal apparatus consists of two pairs of mucosal folds. These folds are false vocal folds (vestibular folds) and true vocal folds (folds). The false vocal folds are covered by respiratory epithelium, while the true vocal folds are covered by stratified squamous epithelium. The false vocal folds are not responsible for sound production, but rather for resonance. The exceptions to this are found in Tibetan Chant and Kargyraa, a style of Tuvan throat singing. Both make use of the false vocal folds to create an undertone. These false vocal folds do not contain muscle, while the true vocal folds do have skeletal muscle.

Other

The most important role of the larynx is its protecting function; the prevention of foreign objects from entering the lungs by coughing and other reflexive actions. A cough is initiated by a deep inhalation through the vocal folds, followed by the elevation of the larynx and the tight adduction (closing) of the vocal folds. The forced expiration that follows, assisted by tissue recoil and the muscles of expiration, blows the vocal folds apart, and the high pressure expels the irritating object out of the throat. Throat clearing is less violent than coughing, but is a similar increased respiratory effort countered by the tightening of the laryngeal musculature. Both coughing and throat clearing are predictable and necessary actions because they clear the respiratory passageway, but both place the vocal folds under significant strain.[8]

Another important role of the larynx is abdominal fixation, a kind of Valsalva maneuver in which the lungs are filled with air in order to stiffen the thorax so that forces applied for lifting can be translated down to the legs. This is achieved by a deep inhalation followed by the adduction of the vocal folds. Grunting while lifting heavy objects is the result of some air escaping through the adducted vocal folds ready for phonation.[8]

Abduction of the vocal folds is important during physical exertion. The vocal folds are separated by about 8 mm (0.31 in) during normal respiration, but this width is doubled during forced respiration.[8]

During swallowing, the backward motion of the tongue forces the epiglottis over the glottis' opening to prevent swallowed material from entering the larynx which leads to the lungs; the larynx is also pulled upwards to assist this process. Stimulation of the larynx by ingested matter produces a strong cough reflex to protect the lungs.

In addition, intrinsic laryngeal muscles (ILM) are spared from muscle wasting disorders, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, may facilitate the development of novel strategies for the prevention and treatment of muscle wasting in a variety of clinical scenarios. ILM have a calcium regulation system profile suggestive of a better ability to handle calcium changes in comparison to other muscles, and this may provide a mechanistic insight for their unique pathophysiological properties [9]

Clinical significance

Disorders

There are several things that can cause a larynx to not function properly.[10] Some symptoms are hoarseness, loss of voice, pain in the throat or ears, and breathing difficulties. Larynx transplant is a rare procedure. The world's first successful operation took place in 1998 at the Cleveland Clinic,[11] and the second took place in October 2010 at the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento.[12]

- Acute laryngitis is the sudden inflammation and swelling of the larynx. It is caused by the common cold or by excessive shouting. It is not serious. Chronic laryngitis is caused by smoking, dust, frequent yelling, or prolonged exposure to polluted air. It is much more serious than acute laryngitis.

- Presbylarynx is a condition in which age-related atrophy of the soft tissues of the larynx results in weak voice and restricted vocal range and stamina. Bowing of the anterior portion of the vocal folds is found on laryngoscopy.

- Ulcers may be caused by the prolonged presence of an endotracheal tube.

- Polyps and nodules are small bumps on the vocal folds caused by prolonged exposure to cigarette smoke and vocal misuse, respectively.

- Two related types of cancer of the larynx, namely squamous cell carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma, are strongly associated with repeated exposure to cigarette smoke and alcohol.

- Vocal cord paresis is weakness of one or both vocal folds that can greatly impact daily life.

- Idiopathic laryngeal spasm.

- Laryngopharyngeal reflux is a condition in which acid from the stomach irritates and burns the larynx. Similar damage can occur with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).[13][14]

- Laryngomalacia is a very common condition of infancy, in which the soft, immature cartilage of the upper larynx collapses inward during inhalation, causing airway obstruction.

- Laryngeal perichondritis, the inflammation of the perichondrium of laryngeal cartilages, causing airway obstruction.

- Laryngeal paralysis is a condition seen in some mammals (including dogs) in which the larynx no longer opens as wide as required for the passage of air, and impedes respiration. In mild cases it can lead to exaggerated or "raspy" breathing or panting, and in serious cases can pose a considerable need for treatment.

- Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, intrinsic laryngeal muscles (ILM) are spared from the lack of dystrophin and may serve as a useful model to study the mechanisms of muscle sparing in dystrophinopathy.[4] Dystrophic ILM presented a significant increase in the expression of calcium-binding proteins. The increase of calcium-binding proteins in dystrophic ILM may permit better maintenance of calcium homeostasis, with the consequent absence of myonecrosis. The results further support the concept that abnormal calcium buffering is involved in dystrophinopathies [15]

Other animals

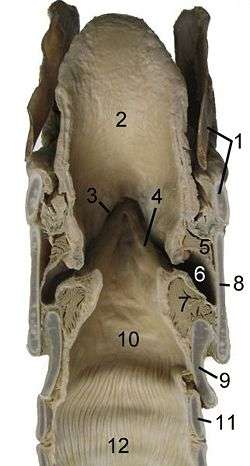

(frontal section, posterior view)

1 hyoid bone; 2 epiglottis; 3 vestibular fold; 4 vocal fold; 5 ventricularis muscle; 6 ventricle of larynx; 7 vocalis muscle; 8 Thyroid Cartilage; 9 Cricoid Cartilage; 10 infraglottic cavity; 11 first tracheal cartilage; 12 trachea

Pioneering work on the structure and evolution of the larynx was carried out in the 1920s by the British comparative anatomist Victor Negus, culminating in his monumental work The Mechanism of the Larynx (1929). Negus, however, pointed out that the descent of the larynx reflected the reshaping and descent of the human tongue into the pharynx. This process is not complete until age six to eight years. Some researchers, such as Philip Lieberman, Dennis Klatt, Brant de Boer and Kenneth Stevens using computer-modeling techniques have suggested that the species-specific human tongue allows the vocal tract (the airway above the larynx) to assume the shapes necessary to produce speech sounds that enhance the robustness of human speech. Sounds such as the vowels of the words see and do, [i] and [u], (in phonetic notation) have been shown to be less subject to confusion in classic studies such as the 1950 Peterson and Barney investigation of the possibilities for computerized speech recognition.[16]

In contrast, though other species have low larynges, their tongues remain anchored in their mouths and their vocal tracts cannot produce the range of speech sounds of humans. The ability to lower the larynx transiently in some species extends the length of their vocal tract, which as Fitch showed creates the acoustic illusion that they are larger. Research at Haskins Laboratories in the 1960s showed that speech allows humans to achieve a vocal communication rate that exceeds the fusion frequency of the auditory system by fusing sounds together into syllables and words. The additional speech sounds that the human tongue enables us to produce, particularly [i], allow humans to unconsciously infer the length of the vocal tract of the person who is talking, a critical element in recovering the phonemes that make up a word.[16]

Non-mammals

Most tetrapod species possess a larynx, but its structure is typically simpler than that found in mammals. The cartilages surrounding the larynx are apparently a remnant of the original gill arches in fish, and are a common feature, but not all are always present. For example, the thyroid cartilage is found only in mammals. Similarly, only mammals possess a true epiglottis, although a flap of non-cartilagenous mucosa is found in a similar position in many other groups. In modern amphibians, the laryngeal skeleton is considerably reduced; frogs have only the cricoid and arytenoid cartilages, while salamanders possess only the arytenoids.[17]

Vocal folds are found only in mammals, and a few lizards. As a result, many reptiles and amphibians are essentially voiceless; frogs use ridges in the trachea to modulate sound, while birds have a separate sound-producing organ, the syrinx.[17]

History

Roman physician Galen first described the larynx, describing it as the "first and supremely most important instrument of the voice"[18]

Additional images

- Larynx.Deep dissection. Anterior view.

- Larinx.Deep dissection. Posterior view.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Larynx. |

| Look up larynx in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Larynx Etymology". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ↑ Collectively, the transverse and oblique arytenoids are known as the interarytenoids.

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4510619/

- 1 2 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mus.20697/abstract

- ↑ "GERD and aspiration in the child: diagnosis and treatment". Grand Rounds Presentation. UTMB Dept. of Otolaryngology. February 23, 2005. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ↑ Laitman & Reidenberg 2009

- ↑ Laitman, Noden & Van De Water 2006

- 1 2 3 Seikel, King & Drumright 2010, Nonspeech laryngeal function, pp. 223–225

- ↑ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.14814/phy2.12409/full

- ↑ Laitman & Reidenberg 1993

- ↑ Jensen, Brenda (January 21, 2011). "Rare transplant gives California woman a voice for the first time in a decade".

- ↑ Johnson, Avery (January 21, 2011). "Woman Finds Her Voice After Rare Transplant". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ Laitman & Reidenberg 1997

- ↑ Lipan, Reidenberg & Laitman 2006

- ↑ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mus.21154/abstract

- 1 2 Lieberman 2006

- 1 2 Romer & Parsons 1977, pp. 214–215, 336

- ↑ Hydman, Jonas (2008). Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. Stockholm. p. 8. ISBN 978-91-7409-123-6.

Sources

- Laitman, J.T.; Noden, D.M.; Van De Water, T.R. (2006). "Formation of the larynx: from homeobox genes to critical periods". In Rubin, J.S.; Sataloff, R.T.; Korovin, G.S. Diagnosis & Treatment Voice Disorders. San Diego: Plural. pp. 3–20. ISBN 9781597560078. OCLC 63279542.

- Laitman, J.T.; Reidenberg, J.S. (1993). "Specializations of the human upper respiratory and upper digestive tract as seen through comparative and developmental anatomy". Dysphagia. 8 (4): 318–325. doi:10.1007/BF01321770. PMID 8269722.

- Laitman, J.T.; Reidenberg, J.S. (1997). "The human aerodigestive tract and gastroesophageal reflux: An evolutionary perspective". Am. J. Med. 103 (Suppl 5A): 3–11. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00313-6. PMID 9422615.

- Laitman, J.T.; Reidenberg, J.S. (2009). "The evolution of the human larynx: Nature's great experiment". In Fried, M.P.; Ferlito, A. The Larynx (3rd ed.). San Diego: Plural. pp. 19–38. ISBN 1597560626. OCLC 183609898.

- Lieberman, P. (2006). Toward an Evolutionary Biology of Language. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02184-3. OCLC 62766735.

- Lipan, M.; Reidenberg, J.S; Laitman, J.T. (2006). "The anatomy of reflux: A growing health problem affecting structures of the head and neck". Anat Rec B New Anat. 289 (6): 261–270. doi:10.1002/ar.b.20120. OCLC 110307385. PMID 17109421.

- Romer, A.S.; Parsons, T.S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- Seikel, J.A.; King, D.W.; Drumright, D.G. (2010). Anatomy & Physiology for Speech, Language, and Hearing (4th ed.). Delmar, NY: Cengage Learning. ISBN 1-4283-1223-4.