Strait of Dover

| Dover Strait | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | North Sea–English Channel (Atlantic Ocean) |

| Coordinates | 51°00′N 1°27′E / 51.000°N 1.450°ECoordinates: 51°00′N 1°27′E / 51.000°N 1.450°E |

| Type | Strait |

| Basin countries |

France England |

| Max. width | 33.3 kilometres (20.7 mi) |

| Average depth | 30 metres (98 ft) |

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait, historically known as the Dover Narrows (French: Pas de Calais [pɑ d(ə)‿kalɛ], "Strait of Calais"; Dutch: Nauw van Calais [nʌu̯ vɑn kaːˈlɛː] or Straat van Dover), is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and North Sea, separating Great Britain from continental Europe. The shortest distance across the strait, 33.3 kilometres (20.7 miles), is from the South Foreland, northeast of Dover in the county of Kent, England, to Cap Gris Nez, a cape near to Calais in the French département of Pas-de-Calais, France. Between these points lies the most popular route for cross-channel swimmers.[1]

On a clear day, it is possible to see the opposite coastline of England from France and vice versa with the naked eye, with the most famous and obvious sight being the white cliffs of Dover from the French coastline and shoreline buildings on both coastlines, as well as lights on either coastline at night, as in Matthew Arnold's poem "Dover Beach".

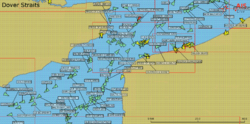

Shipping traffic

Most maritime traffic between the Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea and Baltic Sea passes through the Strait of Dover, rather than taking the longer and more dangerous route around the north of Scotland. The strait is the busiest international seaway in the world, used by over 400 commercial vessels daily. This has made traffic safety a critical issue, with HM Coastguard and its French counterpart maintaining a 24-hour watch over the strait and enforcing a strict regime of shipping lanes.[2]

In addition to the intensive east-west traffic, the strait is crossed from north to south by ferries linking Dover to Calais and Dunkerque. Until 1994 these provided the only surface-based route across it. The Channel Tunnel now provides an alternative route, crossing beneath the strait at an average depth of 45 m (150 feet) below the seabed. The town of Dover gives its name to one of the sea areas of the British Shipping Forecast.

Geological formation

The strait is believed to have been created by the erosion of a land bridge that linked the Weald in Great Britain to the Boulonnais in the Pas de Calais. The predominant geology on both the British and French sides and on the sea floor is chalk. Although somewhat resistant to erosion, erosion of both coasts has created the famous white cliffs of Dover in the UK and the Cap Blanc Nez in France. The Channel Tunnel was bored through solid chalk.

December 2002

The Rhine (as the Urstrom) flowed northwards into the North Sea as the sea level fell during the start of the first of the Pleistocene Ice Ages. The ice created a dam from Scandinavia to Scotland, and the Rhine, combined with the Thames and drainage from much of north Europe, created a vast lake behind the dam, which eventually spilled over the Weald into the English Channel. This overflow channel became the Strait of Dover about 425,000 years ago. A narrow deep channel along the middle of the strait was the bed of the Rhine in the last Ice Age. A geological deposit in East Anglia marks the old preglacial northward course of the Rhine.

A 2007 study[3][4] concluded the English Channel was formed by erosion caused by two major floods. The first was about 425,000 years ago, when an ice-dammed lake in the southern North Sea overflowed and broke the Weald-Artois chalk range in a catastrophic erosion and flood event. Afterwards, the Thames and Scheldt flowed through the gap into the English Channel, but the Meuse and Rhine still flowed northwards. In a second flood about 225,000 years ago the Meuse and Rhine were ice-dammed into a lake that broke catastrophically through a high weak barrier (perhaps chalk, or an end-moraine left by the ice sheet). Both floods cut massive flood channels in the dry bed of the English Channel, somewhat like the Channeled Scablands or the Wabash river in the USA.

The Lobourg strait, a major feature of its sea floor, runs its 6 km wide slash on a north-north-east axis. Nearer to the French coast than to the English coast, it runs along the Varne sandbank where it plunges to 68 m at its deepest, and along the latter's south-east neighbour the Ridge bank (French name "Colbart"[5]) with a maximum depth of 62 m.[6]

Marine wildlife

March 2001

The submarine relief of the strait varies between -68 m at the Lobourg strait, to 20 m at the highest banks. It presents a succession of rocky areas relatively deserted by ships wanting to spare their nets, and of sandy flats and sub-aqueous dunes. The strong currents of the Channel are slowed down around the rocky areas of the strait, with formation of counter-currents and calmer zones where many species can find shelter.[7] In these calmer zones, the water is clearer than in the rest of the strait; thus algae can grow despite the 30 m average depth and help increase diversity in the local species - some of which are infeodated to the strait.

Moreover, this is a transition zone for the species of the Atlantic ocean and those of the southern part of the North sea.

This mix of various environments promotes a wide variety of wildlife.[8]

The « ridens (fr) de Boulogne », a 10- to 20 m deep[9] rocky high-ground partially covered with sand located 15 marine miles to the west of Boulogne-sur-Mer, boasts the highest production of maerl in the strait.[9]

A 682 km2 (262 sq. mi.) area of the strait is classified as a Natura 2000 protection zone listed under the name « Ridens (fr) et dunes hydrauliques du Pas de Calais » ("ridens and sub-aqueous dunes of the Pas de Calais"). This area includes the sub-aqueous dunes of Varne, Colbart, Vergoyer and Bassurelle, the "Ridens de Boulogne", and as its a major characteristic of the Lobourg channel which provides calmer and clearer waters due to its depth reaching -68 m.[10]

The Varne Bank along with its neighbouring bank Colbart, the Vergoyer bank, the ridens (fr) de Boulogne and the French side of the Bassurelle bank, form part of a 680 km2 (262 sq. mi.)

Unusual crossings

Many crossings other than in conventional vessels have been attempted, including by pedalo, jetpack, bathtub, amphibious vehicle and more commonly by swimming. French law bans many of these while British law does not, so most such crossings originate in England.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "English Channel". The Cambridge Paperback Encyclopedia, 1999.

- ↑ See The Channel Navigation Information Service (CNIS)

- ↑ Gupta, Sanjeev; Collier, Jenny S.; Palmer-Felgate, Andy; Potter, Graeme (2007), "Catastrophic flooding origin of shelf valley systems in the English Channel", Nature, 448 (7151): 342–346, Bibcode:2007Natur.448..342G, doi:10.1038/nature06018, PMID 17637667.

- ↑ Europe cut adrift, by Philip Gibbard, pp 259-260, Nature, vol 448, 19 July 2007

- ↑ Pas de Calais - Dover Straight on sea-seek.com.

- ↑ CoastView - What happens offshore?. GEOSYNTH-Project - University of Sussex.

- ↑ Underwater video of the "ridens" (fr), rocky sandbanks in the strait of Dover.

- ↑ (French) Davoult D., Richard A., « Les Ridens, haut-fond rocheux isolé du Pas de Calais: un peuplement remarquable = The Ridens, rocky shallows in the center of the Channel : a distinguished settlement ». Cahiers de biologie marine, Ed. de la station biologique, Roscoff, France (Ref Inist/CNRS)

- 1 2 (French) Natural richesses of the sea, marine nature park of the estuaries of Picardie and the Opal sea.

- ↑ Ridens et dunes hydrauliques du Pas de Calais, Natura 2000.

External links

- Channel Navigation Information Service

- Channel Swimming & Piloting Federation

- Channel Swimming Association

- Depth Chart showing straits and former course of Rhine