Sumerian religion

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

|

Demigods and heroes |

| Related topics |

The Sumerian religion influenced Mesopotamian mythology as a whole, surviving in the mythologies and religions of the Hurrians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and other culture groups.

Worship

Written Cuneiform

Sumerian myths were passed down through the oral tradition until the invention of writing. Early Sumerian cuneiform was used primarily as a record-keeping tool; it was not until the late early dynastic period that religious writings first became prevalent as temple praise hymns[1] and as a form of "incantation" called the nam-šub (prefix + "to cast").[2]

Architecture

In the Sumerian city-states, temple complexes originally were small, elevated one-room structures. In the early dynastic period, temples developed raised terraces and multiple rooms. Toward the end of the Sumerian civilization, Ziggurats became the preferred temple structure for Mesopotamian religious centers.[3] Temples served as cultural, religious, and political headquarters until approximately 2500 BCE, with the rise of military kings known as Lu-gals (“man” + “big”)[2] after which time the political and military leadership was often housed in separate "palace" complexes. Sumer was located in Mesopotamia. This is in the fertile crescent and between the Tigris and Euphrates river.

The Priesthood

Until the advent of the lugals, Sumerian city states were under a virtually theocratic government controlled by various En or Ensí, who served as the high priests of the cults of the city gods. (Their female equivalents were known as Nin.) Priests were responsible for continuing the cultural and religious traditions of their city-state, and were viewed as mediators between humans and the cosmic and terrestrial forces. The priesthood resided full-time in temple complexes, and administered matters of state including the large irrigation processes necessary for the civilization’s survival.

Ceremony

During the Third Dynasty of Ur, the Sumerian city-state of Lagash was said to have had 62 "lamentation priests" who were accompanied by 180 vocalists and instrumentalists.

Cosmology

The Sumerians envisioned the universe as a closed dome surrounded by a primordial saltwater sea.[4] Underneath the terrestrial earth, which formed the base of the dome, existed an underworld and a freshwater ocean called the Apsû. The deity of the dome-shaped firmament was named An; the earth was named Ki. First the underground world was believed to be an extension of the goddess Ki, but later developed into the concept of Kigal. The primordial saltwater sea was named Nammu, who became known as Tiamat during and after the Sumerian Renaissance.

Creation story

According to Sumerian mythology, the gods originally created humans as servants for themselves, but freed them when they became too much to handle.

The primordial union of An and Ki produced Enlil, who became leader of the Sumerian pantheon. After the other deities banished Enlil from Dilmun (the “home of the deities”) for raping the air goddess Ninlil; she had a child, Nanna, god of the moon. Nanna and Ningal gave birth to Inanna, the goddess of war and fertility, and to Utu, god of the sun.[5]

Deities

_01.jpg)

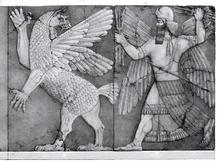

The Sumerians originally practiced a polytheistic religion, with anthropomorphic deities representing cosmic and terrestrial forces in their world. During the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE, Sumerian deities became more anthropocentric and were "...nature gods transformed into city gods." Deities such as Enki and Inanna were viewed as having been assigned their rank, power, and knowledge from An, the heavenly deity, or Enlil, head of the Sumerian pantheon.

This cosmological shift may have been caused by the growing influence of the neighboring Akkadian religion, or as a result of increased warfare between the Sumerian city-states; the assignment of certain powers to deities may have mirrored the appointment of the Lugals, who were given power and authority by the city-state and its priesthood.[6]

Earliest deities

The earliest historical records of Sumer do not go back much further than c. 2900 BC, although it is generally agreed that Sumerian civilization started between c. 4500 and 4000 BC.[7] The earliest Sumerian literature of the 3rd millennium BC identifies four primary deities; Anu, Enlil, Ninhursag and Enki. The highest order of these earliest gods were described occasionally behaving mischievously towards each other, but were generally involved in co-operative creative ordering.[8]

Lists of large numbers of Sumerian deities have been found. Their order of importance and the relationships between the deities has been examined during the study of cuneiform tablets.[9]

Pantheon

The majority of Sumerian deities belonged to a classification called the Anunna (“[offspring] of An”), whereas seven deities, including Enlil and Inanna, belonged to a group of “underworld judges" known as the Anunnaki (“[offspring] of An” + Ki; alternatively, "those from heaven (An) who came to earth (Ki)"]). During the Third Dynasty of Ur, the Sumerian pantheon was said to include sixty times sixty (3600) deities.[10]

The main Sumerian deities are:

- Anu: god of heaven, the firmament

- Enlil: god of the air (from Lil = Air); patron deity of Nippur

- Enki: god of freshwater, male fertility, and knowledge; patron deity of Eridu

- Ereshkigal: goddess of the underworld, Kigal or Irkalla

- Inanna: goddess of warfare, female fertility, and sexual love; patron deity of Uruk

- Nammu was the primeval sea (Engur), who gave birth to An (heaven) and Ki (earth) and the first deities; eventually became known as the goddess Tiamat

- Ninhursag: goddess of the earth[11]

- Nanna: god of the moon; one of the patron deities of Ur[12]

- Ningal: wife of Nanna[13]

- Ninlil: an air goddess and wife of Enlil; one of the matron deities of Nippur; she was believed to reside in the same temple as Enlil[14]

- Ninurta: god of war, agriculture, one of the Sumerian wind gods; patron deity of Girsu, and one of the patron deities of Lagash

- Utu: god of the sun at the E-babbar temple[15] of Sippar

Legacy

Akkadians

The Sumerians had an ongoing linguistic and cultural exchange with the Semitic Akkadian peoples in northern Mesopotamia for generations prior to the usurpation of their territories by Sargon of Akkad in 2340 BCE. Sumerian mythology and religious practices were rapidly integrated into Arabian culture,[16] presumably blending with the original Akkadian belief systems that have been mostly lost to history. Sumerian deities developed Akkadian counterparts. Some remained virtually the same until later Babylonian and Assyrian rule. The Sumerian god An, for example, developed the Akkadian counterpart Anu; the Sumerian god Enki became Ea; and the Sumerian gods Ninurta and Enlil remained very much the same in the Akkadian pantheon.

Babylonians

The Amorite, Babylonians gained dominance over southern Mesopotamia by the mid-17th century BCE. During the Old Babylonian Period, the Sumerian and Akkadian languages were retained for religious purposes; the majority of Sumerian mythological literature known to historians today comes from the Old Babylonian Period,[1] either in the form of transcribed Sumerian texts (most notably the Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh) or in the form of Sumerian and Akkadian influences within Babylonian mythological literature (most notably the Enûma Eliš). The Sumerian-Akkadian pantheon was altered, most notably with the introduction of a new supreme deity, Marduk. The Sumerian goddess Inanna also developed the counterpart Ishtar during the Old Babylonian Period.

Hurrians

The Hurrians adopted the Akkadian god Anu into their pantheon sometime no later than 1200 BCE. Other Sumerian and Akkadian deities adapted into the Hurrian pantheon include Ayas, the Hurrian counterpart to Ea; Shaushka, the Hurrian counterpart to Ishtar; and the goddess Ninlil,[17] whose mythos had been drastically expanded by the Babylonians.

Parallels

Some stories in Sumerian religion appear similar to stories in other Middle-Eastern religions. For example, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, the biblical account of Noah and the flood myth resembles some aspects of the Sumerian deluge myth. The Judaic underworld Sheol is very similar in description with the Sumerian and Babylonian Kigal, ruled by the goddess Ereshkigal and in the Babylonian religion, with their introduced consort, the death god Nergal. Sumerian scholar Samuel Noah Kramer noted similarities between many Sumerian and Akkadian "proverbs" and the later Hebrew proverbs, many of which are featured in the Book of Proverbs.[18]

See also

- Ancient Near Eastern religion

- Ancient Semitic religion

- Babylonian religion

- Mes

- Mesopotamian mythology

- Sumerian literature

References

- 1 2 "Sumerian Literature". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- 1 2 "The Sumerian Lexicon" (PDF). John A. Halloran. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ↑ "Inside a Sumerian Temple". The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship at Brigham Young University. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ "The Firmament and the Water Above" (PDF). Westminster Theological Journal 53 (1991), 232-233. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ↑ "Enlil and Ninlil". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat, (1998). "Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia ", 178-179.

- ↑ Bertman, Stephen (2003). Handbook to life in ancient Mesopotamia. Facts on File. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8160-4346-0.

- ↑ The Sources of the Old Testament: A Guide to the Religious Thought of the Old Testament in Context. Continuum International Publishing Group. 18 May 2004. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-567-08463-7. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ God in Translation: Deities in Cross-cultural Discourse in the Biblical World. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. 2010. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-0-8028-6433-8. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat, (1998). "Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia", 182.

- ↑ "Gilgamec, Enkidu and the nether world". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ↑ "A balbale to Suen (Nanna A)". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ↑ "A balbale to Nanna (Nanna B)". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ↑ "An adab to Ninlil (Ninlil A)". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ↑ "A hymn to Utu (Utu B)". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ↑ "Mesopotamia: the Sumerians". Washington State University. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ "Hurrian Mythology REF 1.2". Christopher B. Siren. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ↑ Samuel Noah Kramer, (1952). "From the Tablets of Sumer", 133-135.

External links

- Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses, on Oracc

- Sumerian Hymns from Cuneiform Texts in the British Museum at Project Gutenberg (Transcription of book from 1908)