Tiamat

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

|

Demigods and heroes |

| Related topics |

In Mesopotamian religion (Sumerian, Assyrian, Akkadian and Babylonian), Tiamat is a primordial goddess of the ocean, mating with Abzû (the god of fresh water) to produce younger gods. She is the symbol of the chaos of primordial creation, depicted as a woman,[1] she represents the beauty of the feminine, depicted as the glistening one.[2] It is suggested that there are two parts to the Tiamat mythos, the first in which Tiamat is a creator goddess, through a "Sacred marriage" between salt and fresh water, peacefully creating the cosmos through successive generations. In the second "Chaoskampf" Tiamat is considered the monstrous embodiment of primordial chaos.[3] Some sources identify her with images of a sea serpent or dragon.[4]

In the Enûma Elish, the Babylonian epic of creation, she gives birth to the first generation of deities; her husband, Apsu, correctly assuming they are planning to kill him and usurp his throne, later makes war upon them and is killed. Enraged, she, too, wars upon her husband's murderers, taking on the form of a massive sea dragon, she is then slain by Enki's son, the storm-god Marduk, but not before she had brought forth the monsters of the Mesopotamian pantheon, including the first dragons, whose bodies she filled with "poison instead of blood". Marduk then forms heavens and the earth from her divided body.

Tiamat was later known as Thalattē (as a variant of thalassa, the Greek word for "sea") in the Hellenistic Babylonian writer Berossus' first volume of universal history. It is thought that the name of Tiamat was dropped in secondary translations of the original religious texts (written in the East Semitic Akkadian language) because some Akkadian copyists of Enûma Elish substituted the ordinary word for "sea" for Tiamat, since the two names had become essentially the same due to association.[5]

Etymology

Thorkild Jacobsen[5] and Walter Burkert both argue for a connection with the Akkadian word for sea, tâmtu, following an early form, ti'amtum.[6]

Burkert continues by making a linguistic connection to Tethys. He finds the later form, thalatth, to be related clearly to Greek Θάλαττα (thalatta) or Θάλασσα (thalassa), "sea". The Babylonian epic Enuma Elish is named for its incipit: "When above" the heavens did not yet exist nor the earth below, Apsu the freshwater ocean was there, "the first, the begetter", and Tiamat, the saltwater sea, "she who bore them all"; they were "mixing their waters". It is thought that female deities are older than male ones in Mesopotamia and Tiamat may have begun as part of the cult of Nammu, a female principle of a watery creative force, with equally strong connections to the underworld, which predates the appearance of Ea-Enki.[7]

Harriet Crawford finds this "mixing of the waters" to be a natural feature of the middle Persian Gulf, where fresh waters from the Arabian aquifer mix and mingle with the salt waters of the sea.[8] This characteristic is especially true of the region of Bahrain, whose name in Arabic means "two seas", and which is thought to be the site of Dilmun, the original site of the Sumerian creation beliefs.[9] The difference in density of salt and fresh water drives a perceptible separation.

Tiamat also has been claimed to be cognate with Northwest Semitic tehom (תהום) (the deeps, abyss), in the Book of Genesis 1:2.[10]

Appearance

In the Enûma Elish her physical description includes a tail, a thigh, "lower parts" (which shake together), a belly, an udder, ribs, a neck, a head, a skull, eyes, nostrils, a mouth, and lips. She has insides (possibly "entrails"), a heart, arteries, and blood.

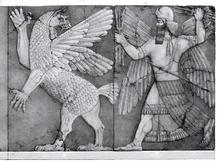

Tiamat is usually described as a sea serpent or dragon, however assyriologist Alexander Heidel disagreed with this identification and argued that "dragon form can not be imputed to Tiamat with certainty". Other scholars have disregarded Heidel's argument: Joseph Fontenrose in particular found it "not convincing" and concluded that "there is reason to believe that Tiamat was sometimes, not necessarily always, conceived as a dragoness".[11] The Enûma Elish states that Tiamat gave birth to dragons and serpents among a more general list of monsters including scorpion men and merpeople, but does not identify her form as that of a dragon; however, other sources containing the same myth do refer to her as such.[12]

The depiction of Tiamat as a multi-headed dragon was popularized in the 1970s as a fixture of the Dungeons & Dragons roleplaying game inspired by earlier sources associating Tiamat with later mythological characters such as Lotan.[13]

Mythology

Abzu (or Apsû) fathered upon Tiamat the elder deities Lahmu and Lahamu (masc. the "hairy"), a title given to the gatekeepers at Enki's Abzu/E'engurra-temple in Eridu. Lahmu and Lahamu, in turn, were the parents of the 'ends' of the heavens (Anshar, from an = heaven, shár = horizon, end) and the earth (Kishar); Anshar and Kishar were considered to meet at the horizon, becoming, thereby, the parents of Anu (Heaven) and Ki (Earth).

Tiamat was the "shining" personification of salt water who roared and smote in the chaos of original creation. She and Apsu filled the cosmic abyss with the primeval waters. She is "Ummu-Hubur who formed all things".

In the myth recorded on cuneiform tablets, the deity Enki (later Ea) believed correctly that Apsu was planning to murder the younger deities, upset with the chaos they created, and so captured him and held him prisoner beneath his temple the E-Abzu. This angered Kingu, their son, who reported the event to Tiamat, whereupon she fashioned eleven monsters to battle the deities in order to avenge Apsu's death. These were her own offspring: Bašmu (“Venomous Snake”), Ušumgallu (“Great Dragon”), Mušmaḫḫū (“Exalted Serpent”), Mušḫuššu (“Furious Snake”), Laḫmu (the “Hairy One”), Ugallu (the “Big Weather-Beast”), Uridimmu (“Mad Lion”), Girtablullû (“Scorpion-Man"), Umū dabrūtu (“Violent Storms"), Kulullû (“Fish-Man") and Kusarikku (“Bull-Man”).

Tiamat possessed the Tablet of Destinies and in the primordial battle she gave them to Kingu, the deity she had chosen as her lover and the leader of her host, and who was also one of her children. The deities gathered in terror, but Anu, (replaced later, first by Enlil and, in the late version that has survived after the First Dynasty of Babylon, by Marduk, the son of Ea), first extracting a promise that he would be revered as "king of the gods", overcame her, armed with the arrows of the winds, a net, a club, and an invincible spear.

- And the lord stood upon Tiamat's hinder parts,

- And with his merciless club he smashed her skull.

- He cut through the channels of her blood,

- And he made the North wind bear it away into secret places.

Slicing Tiamat in half, he made from her ribs the vault of heaven and earth. Her weeping eyes became the source of the Tigris and the Euphrates, her tail became the Milky Way. With the approval of the elder deities, he took from Kingu the Tablet of Destinies, installing himself as the head of the Babylonian pantheon. Kingu was captured and later was slain: his red blood mixed with the red clay of the Earth would make the body of humankind, created to act as the servant of the younger Igigi deities.

The principal theme of the epic is the justified elevation of Marduk to command over all the deities. "It has long been realized that the Marduk epic, for all its local coloring and probable elaboration by the Babylonian theologians, reflects in substance older Sumerian material," American Assyriologist E. A. Speiser remarked in 1942[14] adding "The exact Sumerian prototype, however, has not turned up so far." Without corroboration in surviving texts, this surmise that the Babylonian version of the story is based upon a modified version of an older epic, in which Enlil, not Marduk, was the god who slew Tiamat,[15] is more recently dismissed as "distinctly improbable",[16] in fact, Marduk has no precise Sumerian prototype. It is generally accepted amongst modern Assyriologists that the Enûma Elish - the Babylonian creation epic to which this mythological strand is attributed - has been written as political and religious propaganda rather than reflecting a Sumerian tradition; the dating of the epic is not completely clear, but judging from the mythological topics covered and the cuneiform versions discovered thus far, it is likely to date it to the 15th century BCE.

Interpretations

The Tiamat myth is one of the earliest recorded versions of the Chaoskampf, the battle between a culture hero and a chthonic or aquatic monster, serpent or dragon.[17] Chaoskampf motifs in other mythologies linked directly or indirectly to the Tiamat myth include the Hittite Illuyanka myth, and in Greek tradition Apollo's killing of the Python as a necessary action to take over the Delphic Oracle.[18]

According to some analyses there are two parts to the Tiamat myth, the first in which Tiamat is creator goddess, through a "sacred marriage" between salt and fresh water, peacefully creating the cosmos through successive generations. In the second "Chaoskampf" Tiamat is considered the monstrous embodiment of primordial chaos.[3]

Robert Graves[19] considered Tiamat's death by Marduk as evidence for his hypothesis of an ancient shift in power from a matriarchal society to a patriarchy. Grave's ideas were later developed into the Great Goddess theory by Marija Gimbutas, Merlin Stone and others. The theory suggests Tiamat and other ancient monster figures were presented as former supreme deities of peaceful, woman-centered religions that were turned into monsters when violent. Their defeat at the hands of a male hero corresponded to the manner in which male-dominated religions overthrew ancient society. This theory is rejected by academia and modern authors such as Lotte Motz, Cynthia Eller and others.[20][21]

As Omoroca

Fragments of Chaldean History, Berossus: From Alexander Polyhistor:

"Berossus, in the first book of his history of Babylonia, informs us that he lived in the age of Alexander the son of Philip. And he mentions that there were written accounts, preserved at Babylon with the greatest care, comprehending a period of above fifteen myriads of years: and that these writings contained histories of the heaven and of the sea; of the birth of mankind; and of the kings, and of the memorable actions which they had achieved.

He wrote of Omoroca:

"There was a time in which there existed nothing but darkness and an abyss of waters, wherein resided most hideous beings, which were produced of a two-fold principle. There appeared men, some of whom were furnished with two wings, others with four, and with two faces. They had one body but two heads: the one that of a man, the other of a woman: and likewise in their several organs both male and female.

Other human figures were to be seen with the legs and horns of goats: some had horses' feet: while others united the hind quarters of a horse with the body of a man, resembling in shape the hippocentaurs. Bulls likewise were bred there with the heads of men; and dogs with fourfold bodies, terminated in their extremities with the tails of fishes: horses also with the heads of dogs: men too and other animals, with the heads and bodies of horses and the tails of fishes.

In short, there were creatures in which were combined the limbs of every species of animals. In addition to these, fishes, reptiles, serpents, with other monstrous animals, which assumed each other's shape and countenance. Of all which were preserved delineations in the temple of Belus at Babylon.

The person, who presided over them, was a woman named Omoroca; which in the Chaldæan language is Thalatth; in Greek Thalassa, the sea; but which might equally be interpreted the Moon. All things being in this situation, Belus came, and cut the woman asunder: and of one half of her he formed the earth, and of the other half the heavens; and at the same time destroyed the animals within her."

All this (he says) was an allegorical description of nature. For, the whole universe consisting of moisture, and animals being continually generated therein, the deity above-mentioned took off his own head: upon which the other gods mixed the blood, as it gushed out, with the earth; and from thence were formed men. On this account it is that they are rational, and partake of divine knowledge.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Luzacs Semitic Text and Translation Series (PDF) (Vol XII ed.). p. 150-line 122.

- ↑ Luzacs Semitic Text and Translation Series (PDF) (Vol XII ed.). p. 124-line 36.

- 1 2 Dalley, Stephanie (1987). Myths from Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. p. 329.

- ↑ Such as Jacobsen, Thorkild (1968). "The Battle between Marduk and Tiamat". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 88 (1): 104–108. doi:10.2307/597902. JSTOR 597902.

- 1 2 Jacobsen 1968:105.

- ↑ Burkert, Walter. The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influences on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age 1993, p 92f.

- ↑ Steinkeller, Piotr. "On Rulers, Priests and Sacred Marriage: tracing the evolution of early Sumerian kingship" in Wanatabe, K. (ed.), Priests and Officials in the Ancient Near East (Heidelberg 1999) pp.103–38

- ↑ Crawford, Harriet E. W. (1998), Dilmun and its Gulf Neighbours (Cambridge University Press).

- ↑ Crawford, Harriet; Killick, Robert and Moon, Jane, eds.. (1997). The Dilmun Temple at Saar: Bahrain and Its Archaeological Inheritance (Saar Excavation Reports / London-Bahrain Archaeological Expedition: Kegan Paul)

- ↑ Yahuda, A., The Language of the Pentateuch in its Relation to Egyptian (Oxford, 1933)

- ↑ Fontenrose, Joseph (1980). Python: a study of Delphic myth and its origins. University of California Press. pp. 153–154. ISBN 0-520-04091-0.

- ↑ King, Leonard William (1902). The Seven Tablets of Creation (Vol. II: Supplementary Texts). p. 117.

- ↑ Four ways of Creation: "Tiamat & Lotan." Retrieved on August 23, 2010

- ↑ Speiser, "An Intrusive Hurro-Hittite Myth", Journal of the American Oriental Society 62.2 (June 1942:98–102) p. 100.

- ↑ Expressed, for example, in E. O. James, The Worship of the Skygod: A Comparative Study in Semitic and Indo-European Religion (London: University of London, Jordan Lectures in Comparative religion) 1963:24, 27f.

- ↑ As by W. G. Lambert, reviewing James 1963 in Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 27.1 (1964), pp. 157–158.

- ↑ e.g. Thorkild Jacobsen in "The Battle between Marduk and Tiamat", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 88.1 (January–March 1968), pp 104–108.

- ↑ MArtkheel

- ↑ Graves, The Greek Myths, rev. ed. 1960:§4.5.

- ↑ The Faces of the Goddess, Lotte Motz, Oxford University Press (1997), ISBN 978-0-19-508967-7

- ↑ The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why An Invented Past Will Not Give Women a Future, Cynthia Eller, Beacon Press (2000), ISBN 978-0-8070-6792-5.

- ↑ "Fragments of Chaldean History, Berossus:From Alexander Polyhistor.". Retrieved 24 May 2012.