Superman

| Superman | |

|---|---|

|

Art by Alex Ross | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

| First appearance | Action Comics #1 (June 1938) |

| Created by |

Jerry Siegel Joe Shuster |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego |

Kal-El (birth name) Clark Kent (adopted name) |

| Species | Kryptonian |

| Place of origin | Krypton |

| Team affiliations |

Justice League Legion of Super-Heroes |

| Partnerships | |

| Abilities |

|

Superman is a fictional superhero appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, high school students living in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1933. They sold Superman to Detective Comics, the future DC Comics, in 1938. Superman debuted in Action Comics #1 (cover-dated June 1938) and subsequently appeared in various radio serials, newspaper strips, television programs, films, and video games. With this success, Superman helped to create the superhero archetype and establish its primacy within the American comic book.[1] The character is also referred to by such epithets as the Man of Steel, the Man of Tomorrow, and The Last Son of Krypton.[2]

The origin story of Superman relates that he was born Kal-El on the alien planet Krypton, before being rocketed to Earth as an infant by his scientist father Jor-El, moments before Krypton's destruction. Discovered and adopted by a Kansas farmer and his wife, the child is raised as Clark Kent and imbued with a strong moral compass. Very early on he started to display various superhuman abilities, which, upon reaching maturity, he resolved to use for the benefit of humanity through a secret "Superman" identity.

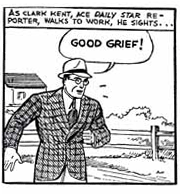

Superman resides and operates in the fictional American city of Metropolis. As Clark Kent, he is a journalist for the Daily Planet, a Metropolis newspaper. Superman's love interest is generally Lois Lane, and his archenemy is supervillain Lex Luthor. He is typically a member of the Justice League and close ally of Batman and Wonder Woman. Like other characters in the DC Universe, several alternate versions of Superman have been depicted over the years.

Superman's appearance is distinctive and iconic; he usually wears a blue costume with a red-and-yellow emblem on the chest, consisting of the letter S in a shield shape, and a red cape. This shield is used in many media to symbolize the character. Superman is widely considered an American cultural icon.[1][3][4][5] He has fascinated scholars, with cultural theorists, commentators, and critics alike exploring the character's impact and role in the United States and worldwide. The character's ownership has often been the subject of dispute, with Siegel and Shuster twice suing for the return of rights. The character has been adapted extensively and portrayed in other forms of media as well, including films, television series, and video games. Several actors have portrayed Superman in motion pictures and TV series including Kirk Alyn, George Reeves, Christopher Reeve, Tom Welling, Brandon Routh, Henry Cavill, and Tyler Hoechlin.

Creation and conception

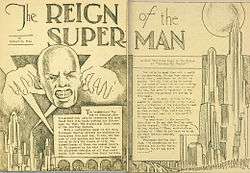

In January 1933, Cleveland high school student[6] Jerry Siegel wrote a short story, illustrated by his friend and classmate Joe Shuster, titled "The Reign of the Superman", which Siegel self-published in his fanzine, Science Fiction. The titular character is a vagrant who gains vast psychic powers from an experimental drug and uses them maliciously for profit and amusement, only to lose them and become a vagrant again, ashamed that he will be remembered only as a villain.[7] Siegel's fanzine did not sell well. Siegel and Shuster shifted to making comic strips, which they self-published in a book they called Popular Comics. The pair dreamed of becoming professional authors and believed that syndicated newspaper strips offered more lucrative and stable work than pulp magazines. The art quality standards were also lower, making them more accessible to the inexperienced Shuster.[8]

In early 1933 or in 1934,[9] Siegel developed a new character, also named Superman, but now a heroic character, which Siegel felt would be more marketable.[10] This first prototype of Superman had no fantastic abilities and wore casual clothing. Siegel and Shuster often compared this version to Slam Bradley, a comics character they created in 1936.[11][12]

Siegel shared his idea with Shuster and they decided to turn it into a comic strip. The first publisher they solicited was Humor Publishing in Chicago, after having read one of their comic books, Detective Dan.[13][14][15] A representative of Humor Publishing was due to visit Cleveland on a business trip and so Siegel and Shuster hastily put together a comic story titled "The Superman" and presented it to the publisher.[16] Although Humor showed interest, it pulled out of the comics business before any book deal could be made.[17]

Siegel believed publishers kept rejecting them because he and Shuster were young and unknown, so he looked for an established artist to replace Shuster.[18] When Siegel told Shuster what he was doing, Shuster reacted by burning their rejected Superman comic, sparing only the cover.[19][20]

Siegel solicited multiple artists[18][21] and in 1934 Russell Keaton,[21] who worked on the Buck Rogers comic strip, responded. In nine sample strips Keaton produced based on Siegel's treatment, the Superman character further evolves: In the distant future, when Earth is on the verge of exploding due to "giant cataclysms", the last surviving man sends his child back in time to the year 1935, where he is adopted by Sam and Molly Kent. The boy exhibits superhuman strength and bulletproof skin, and the Kents teach the child, whom they name Clark, to use his powers for good.[22][23] However, the newspaper syndicates rejected their work and Keaton abandoned the project.[24]

Siegel and Shuster reconciled and resumed developing Superman. The character became an alien from the planet Krypton with the now-familiar costume: tights with an "S" on the chest, over-shorts, and a cape.[25][26][27] They made Clark Kent a journalist who pretends to be timid, and introduced his colleague Lois Lane, who is attracted to the bold and mighty Superman but does not realize he and Kent are the same person.[28]

Siegel and Shuster entered the comics field professionally in 1935, producing detective and adventure stories for the New York-based comic-book publisher National Allied Publications. Although National expressed interest in Superman,[29] Siegel and Shuster wanted to sell Superman as a syndicated comic strip, but the newspaper syndicates all turned them down.[30] Max Gaines, who worked at McClure Newspaper Syndicate, suggested they show their work to Detective Comics (which had recently bought out National Allied).[31] Siegel recalled, In March 1938, Siegel and Shuster sold all rights to the character to Detective Comics, Inc.[32] for $130 (the equivalent of $2,200 when adjusted for inflation).[33][34] It was the company's policy to buy the full rights to the characters it published.[35] By this time, they had resigned themselves that Superman would never be a success, and with this deal they would at least see their character finally published.[36]

Influences

Siegel and Shuster read pulp science-fiction and adventure magazines, and many stories featured characters with extraordinary powers such as telepathy, clairvoyance, and superhuman strength. An influence was Edgar Rice Burroughs' John Carter of Mars, a human who was displaced to Mars, where the low gravity makes him stronger than the natives and allows him to leap great distances.[37] While it is widely assumed that the 1930 Philip Wylie novel Gladiator, featuring a protagonist, Hugo Danner, with similar powers, was an inspiration for Superman,[38][39] Siegel denied this.[40]

Siegel and Shuster were also avid moviegoers.[41] Shuster based Superman's stance and devil-may-care attitude on that of Douglas Fairbanks, who starred in adventure films such as The Mark of Zorro and Robin Hood.[42] The name of Superman's home city, Metropolis, was taken from the 1927 film of the same name.[41] Popeye cartoons were also an influence.[43]

The persona of Clark Kent was inspired by slapstick comedian Harold Lloyd. Lloyd wore glasses and often played gentle characters who were abused by bullies, but later in the story would snap and fight back furiously. Shuster, who also wore glasses and described himself as "mild-mannered", found Lloyd's characters relatable.[44] Kent is a journalist because Siegel often imagined himself becoming one after leaving school. The inclusion of a romantic subplot with Lois Lane was inspired by Siegel's own awkwardness with girls.[45]

The pair collected comic strips in their youth, with a favorite being Winsor McCay's fantastical Little Nemo.[41] Shuster remarked on the artists which played an important part in the development of his own style: "Alex Raymond and Burne Hogarth were my idols – also Milt Caniff, Hal Foster, and Roy Crane."[41] Shuster taught himself to draw by tracing over the art in the strips and magazines they collected.[17]

As a boy, Shuster was obsessed with fitness culture[43] and a fan of strongmen such as Siegmund Breitbart and Joseph Greenstein. He collected fitness magazines and manuals and used their photographs as visual references for his art.[17]

The visual design of Superman came from multiple influences. The tight-fitting suit and shorts were inspired by the costumes of wrestlers, boxers, and strongmen. Shuster first gave Superman laced sandals like those of strongmen and classical heroes.[46] The emblem on his chest may have been inspired by the uniforms of athletic teams. Many pulp action heroes such as swashbucklers wore capes. Superman's face was based on Johnny Weissmuller's.[17]

The word "superman" was commonly used in the 1920s and 1930s to describe men of great ability, most often athletes and politicians.[47] It occasionally appeared in pulp fiction stories as well, such as "The Superman of Dr. Jukes"[48] and Doc Savage.[49] It is unclear whether Siegel and Shuster were influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of the Übermensch;[50] they never acknowledged as much.[51]

Publication history

Comic books and comic strips

Superman debuted as the cover feature of the anthology Action Comics #1 (cover-dated June 1938 and published on April 18, 1938).[52] The series was an immediate success,[53] and reader feedback showed that Superman was responsible.[54] In June 1939, Detective Comics began a sister series, Superman, dedicated exclusively to the character.[55] Action Comics eventually became dedicated to Superman stories too, and both it and Superman have been published without interruption since 1938 (ignoring changes to the titles and numbering).[56][57] A large number of other series and miniseries have been published as well.[58] Superman has also appeared as a regular or semi-regular character in a number of superhero team series, such as Justice League of America and World's Finest Comics, and in spin-off series such as Supergirl. Sales of Action Comics and Superman declined steadily from the 1950s,[59][60] but rose again starting in 1987. Superman #75 (Nov 1992) sold over 6 million copies, making it the best-selling issue of a comic book of all time,[61] thanks to a media sensation over the possibly permanent death of the character in that issue.[62] Sales declined from that point on. In February 2016, Action Comics sold just over 31,000 copies.[63] The comic books are today considered a niche aspect of the Superman franchise due to low readership.[64]

Beginning in January 1939, a Superman daily comic strip appeared in newspapers, syndicated through the McClure Syndicate. A color Sunday version was added that November. The Sunday strips had a narrative continuity separate from the daily strips, possibly because Siegel had to delegate the Sunday strips to ghostwriters.[65] By 1941, the newspaper strips had an estimated readership of 20 million.[66] Shuster drew the early strips, then passed the job to Wayne Boring.[67] From 1949 to 1956, the newspaper strips were drawn by Win Mortimer.[68] The strip ended in May 1966, but was revived from 1977 to 1983 to coincide with a series of movies released by Warner Bros.[69]

After Shuster left National, Boring also succeeded him as the principal artist on Superman comic books.[70] He redrew Superman taller and more detailed.[71] Around 1955, Curt Swan in turn succeeded Boring.[72]

Creative management

Initially, Siegel was allowed to write Superman more or less as he saw fit,[73] because nobody had anticipated the success and rapid expansion of the franchise.[74] But soon Siegel and Shuster's work was put under careful oversight for fear of trouble with censors.[75] Siegel was forced to tone down the violence and social crusading that characterized his early stories.[76] Editor Whitney Ellsworth, hired in 1940, dictated that Superman not kill.[77] Sexuality was banned, and colorfully outlandish villains such as Ultra-Humanite and Toyman were thought to be less nightmarish for young readers.[78]

Mort Weisinger was the editor on Superman comics from 1941 to 1970, his tenure briefly interrupted by military service. Siegel and his fellow writers had developed the character with little thought of building a coherent mythology, but as the number of Superman titles and the pool of writers grew, Weisinger demanded a more disciplined approach.[79] Weisinger assigned story ideas, and the logic of Superman's powers, his origin, the locales, and his relationships with his growing cast of supporting characters were carefully planned. Elements such as Bizarro, Supergirl, the Phantom Zone, alternate varieties of kryptonite, robot doppelgangers, and Krypto were introduced. The complicated universe built under Weisinger was beguiling to devoted readers but alienating to casuals.[80] Weisinger favored lighthearted stories over serious drama, and avoided sensitive subjects such as the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement because he feared his right-wing views would alienate his writing staff and readers.[81] Weisinger also introduced letters columns in 1958 to encourage feedback and build intimacy with readers.[82] Superman was the best-selling comic book character of the 1960s.[83][84]

Weisinger retired in 1970 and Julius Schwartz took over. By his own admission, Weisinger had grown out of touch with newer readers.[85] Schwartz updated Superman by removing overused plot elements such as kryptonite and robot doppelgangers and making Clark Kent a television anchor.[86] Schwartz also scaled Superman's powers down to a level closer to Siegel's original. These changes would eventually be reversed by later writers. Schwartz allowed stories with serious drama, as in "For the Man Who Has Everything" (Superman Annual #11), in which the villain Mongul torments Superman with an illusion of happy family life on a living Krypton.

Schwartz retired from DC Comics in 1986, and was succeeded by Mike Carlin as editor on Superman comics His retirement coincided with DC Comics' decision to streamline the shared continuity called the DC Universe with the companywide-crossover storyline "Crisis on Infinite Earths". Writer John Byrne rewrote the Superman mythos, again reducing Superman's powers, which writers had slowly re-strengthened, and revised many supporting characters, such as making Lex Luthor a billionaire industrialist rather than a mad scientist, and making Supergirl an artificial shapeshifting organism because DC wanted Superman to be the sole surviving Kryptonian.

Carlin was promoted to Executive Editor for the DC Universe books in 1996, a position he held until 2002. K.C. Carlson took his place as editor of the Superman comics.

The 1940s radio serial was produced by Robert Maxwell and Allen Ducovny, who were employees of Superman, Inc. and Detective Comics, respectively.[87][88] Robert Maxwell was later hired to produce the TV show starring George Reeves. DC Comics (then known as National Comics Publications) felt that the first season was too violent for what they expected to be a children's show, so they removed Maxwell and replaced him with Whitney Ellsworth, a veteran writer and editor at National Comics.[89] DC Comics had approval rights over all creative aspects of the Superboy TV series (1988-1992), from scripts to casting to shooting revisions.[90]

The first three movies starring Christopher Reeve were produced by Alexander and Ilya Salkind. When Warner Bros sold the movie rights to Superman to the Salkinds in 1974, it demanded control over the budget and the casting but left everything else to the producers' discretion.[91] These movies influenced future stories, with the Salkinds insisting Clark Kent be a newspaper journalist, in order to appeal to older fans.[92] Kent left his TV anchor job and returned to the Daily Planet. Innovations such as John Barry's crystalline set designs for Krypton and the Fortress of Solitude, Superman's chest emblem being his family crest, and screenwriter Mario Puzo's messianic themes were also adopted by the comics' writers.

Aesthetic style

In the earlier decades of Superman comics, artists were expected to conform to a certain "house style".[93] Joe Shuster defined the aesthetic style of Superman in the 1940s, and not just in the comics: he also provided character model sheets for the Fleischer & Famous animated serial of the 1940s.[94] After Shuster left National, Wayne Boring succeeded him as the principal artist on Superman comic books.[70] He redrew Superman taller and more detailed.[71] Around 1955, Curt Swan in turn succeeded Boring.[72] The 1980s saw a boom in the diversity of comic book art and now there is no single "house style" in Superman comics.[95]

Copyright battles

Ownership lawsuits

Siegel wrote most of the comic-book and daily newspaper stories until he was conscripted in 1943.[96] While Siegel was serving in Hawaii, Detective Comics introduced a child version of Superman called "Superboy", based on a concept Siegel had submitted several years before. Siegel was furious because Detective did this without having bought the character.[97] After Siegel's discharge from the Army, he and Shuster sued Detective Comics in 1947 for the rights to Superman and Superboy. The judge ruled that the March 1938 sale of Superman was binding, but that Superboy was a separate entity that rightfully belonged to Siegel. Siegel and Shuster settled out-of-court with Detective, which paid the pair $94,000 ($930,000 when adjusted for inflation) in exchange for the full rights to both Superman and Superboy.[98] Detective then fired Siegel and Shuster.[99]

In 1969, Siegel and Shuster attempted to regain rights to Superman using the renewal option in the Copyright Act of 1909, but the court ruled Siegel and Shuster had transferred the renewal rights to Detective Comics in 1938. Siegel and Shuster appealed, but the appeals court upheld this decision. Detective had re-hired Siegel as a writer in 1957, but fired him again when he filed this second lawsuit.

In 1975, Siegel and a number of other comic book writers and artists launched a public campaign for better compensation and treatment of comic creators. Warner Brothers agreed to give Siegel and Shuster a yearly stipend, full medical benefits, and credit their names in all future Superman productions in exchange for never contesting ownership of Superman. Siegel and Shuster upheld this bargain.[17]

Shuster died in 1992. DC Comics offered Shuster's heirs a stipend in exchange for never challenging ownership of Superman, which they accepted for some years.[98]

Siegel died in 1996. His heirs attempted to take the rights to Superman using the termination provision of the Copyright Act of 1976. DC Comics negotiated an agreement wherein it would pay the Siegel heirs several million dollars and a yearly stipend of $500,000 in exchange for permanently granting DC the rights to Superman. DC Comics also agreed to insert the line "By Special Arrangement with the Jerry Siegel Family" in all future Superman productions.[100] The Siegels accepted DC's offer in an October 2001 letter.[98]

Copyright lawyer and movie producer Marc Toberoff then struck a deal with the heirs of both Siegel and Shuster to help them get the rights to Superman in exchange for signing the rights over to his production company, Pacific Pictures. Both groups accepted. The Siegel heirs called off their deal with DC Comics and in 2004 sued DC for the rights to Superman and Superboy. In 2008, the judge ruled in favor of the Siegels. DC Comics appealed the decision, and the appeals court ruled in favored of DC, arguing that the October 2001 letter was binding. In 2003, the Shuster heirs served a termination notice for Shuster's grant of his half of the copyright to Superman. DC Comics sued the Shuster heirs in 2010, and the court ruled in DC's favor on the grounds that the 1992 agreement with the Shuster heirs barred them from terminating the grant.[98]

Superman is due to enter the public domain in 2033.[98] However, this would only apply to the character as he is depicted in Action Comics #1 (1938). Later developments, such as his power of "heat vision" (introduced in 1949), may persist under copyright until the works they were introduced in enter the public domain themselves.[101]

Copyright infringement lawsuits

Superman's success quickly spawned a wave of imitations, and Detective Comics defended its copyright vigorously.[102] Will Eisner created a character called Wonder Man in 1939, but a lawsuit from Detective Comics forced its cancellation after just one issue.[103] Fawcett Comics introduced Captain Marvel in 1940 and for some years that character outsold Superman, but after protracted legal battles Fawcett was forced to cease publishing Captain Marvel in 1953.

Fictional character biography

In Action Comics #1 (April 1938), Superman is born on an alien world to a technologically advanced species that resembles humans. When his world is on the verge of destruction, his father, a scientist, places his infant son alone in a spaceship that takes him to Earth. The earliest newspaper strips name the planet "Krypton", the baby "Kal-L", and his biological parents "Jor-L" and "Lora";[104] their names become "Jor-el", and "Lara" in a 1942 spinoff novel by George Lowther.[105] The ship lands in the American countryside, where the baby is adopted by the Kents. In the original stories, they adopt him from an orphanage.[106] The Kents name the boy Clark and raise him in a farming community. A 1947 episode of the radio serial places the then-unnamed community in Iowa.[107] It is named Smallville in Superboy #2 (June 1949). New Adventures of Superboy #22 (Oct. 1981) places it in Maryland. The 1978 Superman movie and most stories since place it in Kansas.[108]

The Kents teach Clark he must conceal his otherworldly origins and use his fantastic powers to do good. Clark creates the costumed identity of Superman so as to protect his personal privacy and the safety of his loved ones. As Clark Kent, he wears eyeglasses to disguise his face and wears his Superman costume underneath his clothes so that he can change at a moment's notice. To complete this disguise, Clark avoids violent confrontation, preferring to slip away and change into Superman when danger arises, and suffers occasional ridicule for his apparent cowardice.

Writers developed Superman's powers gradually. Since the beginning, he has had superhuman strength and a nigh-invulnerable body. In the earliest comics, Superman travels by running and leaping. In the radio serial that began in 1940, Superman has the ability to fly.[109] Fleischer Studios also depicted Superman flying in a theatrical animated series they produced that same decade, because this required fewer frames of animation,[110] and their animation tests of Superman leaping looked "silly" anyway.[111] X-ray vision is introduced in Action Comics #11 (April 1939) and heat vision in Superman #59 (Aug. 1949). Originally, Superman's powers were common on Krypton, but in later stories they are activated by the light of Earth's yellow sun, and can be deactivated by red sunlight similar to that of Krypton's sun.

Siegel understood that Superman's invulnerability diminished his appeal as an action hero, and so wrote a story introducing "K-metal", whose radiation harms Superman. This draft was never published since the story had Superman reveal his secret identity to Lois,[112] but the writers of the radio serial took inspiration and introduced the green mineral kryptonite in a 1943 episode.[113] It first appeared in comics in the story "Superman Returns To Krypton!", credited to writer Bill Finger, in Superman #61 (Dec. 1949).[114]

Clark works as a newspaper journalist. In the earliest stories, he is employed by George Taylor of The Daily Star, but the second episode of the radio serial changed this to Perry White of The Daily Planet.[115] Action Comics #1 introduced Clark's colleague Lois Lane. Clark is romantically attracted to her, but she rejects the mild-mannered Clark and is infatuated with the bold and mighty Superman. This love triangle was conceived in 1934 and is present in most Superman stories. Jerry Siegel objected to any proposal that Lois discover that Clark is Superman because he felt that, as implausible as Clark's disguise is, the love triangle was too important to the book's appeal.[116] For decades in comic stories, Lois suspects Clark is Superman and tries to prove it, but Superman always outwits her; the first such story was Superman #17 (1942).[117][118]

In Action Comics #662 (Feb. 1991) in a story by writer Roger Stern and artist Bob McLeod, Lois definitively learns of Clark's dual identity,[119] a status quo that would exist for two decades and was reflected in a 1995 episode of the TV series Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman.[120] Both in that series and in the 1996 comic book special Superman: The Wedding Album, Clark and Lois marry.[121] The couple's biological child, Jonathan Samuel Kent, was born in Convergence: Superman #2 (July 2015).

The first story in which Superman dies was published in Superman #188 (April 1966) in which he is killed by kryptonite radiation, but is revived in the same issue by one of his android doppelgangers. In the 1990s The Death and Return of Superman story arc, after a deadly battle with Doomsday, Superman died in Superman #75 (Jan. 1993). He was later revived by the Eradicator. In Superman #52 (May 2016) Superman is killed by kryptonite poisoning, and this time he was not resurrected but replaced by the Superman of a previous continuity.

In 2011, DC Comics rebooted its continuity and relaunched its entire line of comic books under the rubric The New 52, with a new version of Superman as the protagonist of the Superman books. In this new version of events, Clark's parents are now dead at the hands of a drunk driver when he was a teenager, and he is not married to Lois.[122] In Superman vol. 2, #43 (October 2015) Superman's identity is exposed to the world.[120][123][124] The pre-New 52 version of Superman was re-introduced in the comic book series Superman: Lois and Clark [125] and for a time Earth had two superheroes each called Superman. The older, more mature Superman remained on Earth after the younger Superman died in Superman vol. 3, #52 (May 25, 2016).

In June 2016, DC Comics once again relaunched its comic book titles with DC Rebirth. The publisher re-established the pre-New 52 Superman as the protagonist of the new comic books, with Lois Lane as his wife once more. He and Lois also conceive a biological son, Jonathan Samuel Kent, who eventually becomes Superboy.[126]

Personality

In the original Siegel and Shuster stories, Superman's personality is rough and aggressive. The character often attacks and terrorizes wife beaters, profiteers, lynch mobs, and gangsters in a rough manner and with a looser moral code than audiences today might be used to.[127] Although not as ruthless as the early Batman, Superman in the comics of the 1930s is unconcerned about the harm his strength may cause. He tosses villainous characters in such a manner that fatalities would presumably occur, although these are seldom shown explicitly on the page. This came to an end in late 1940 when new editor Whitney Ellsworth instituted a code of conduct for his characters to follow, banning Superman from ever killing.[128] The character was softened and given a sense of humanitarianism. Ellsworth's code, however, is not to be confused with "the Comics Code", which was created in 1954 by the Comics Code Authority and ultimately abandoned by every major comic book publisher by the early 21st century.[129]

In his first appearances, Superman was considered a vigilante by the authorities, being fired upon by the National Guard as he razed a slum so that the government would create better housing conditions for the poor. By 1942, however, Superman was working side-by-side with the police.[130][131] Today, Superman is commonly seen as a brave and kind-hearted hero with a strong sense of justice, morality, and righteousness. He adheres to an unwavering moral code instilled in him by his adoptive parents.[132] His commitment to operating within the law has been an example to many citizens and other heroes but has stirred resentment and criticism among others, who refer to him as the "big blue boy scout." Superman can be rather rigid in this trait, causing tensions in the superhero community.[133] This was most notable with Wonder Woman, one of his closest friends, after she killed Maxwell Lord.[133] Booster Gold had an initial icy relationship with the Man of Steel but grew to respect him.[134]

Having lost his home world of Krypton, Superman is very protective of Earth,[135] and especially of Clark Kent's family and friends. This same loss, combined with the pressure of using his powers responsibly, has caused Superman to feel lonely on Earth, despite having his friends and parents. Previous encounters with people he thought to be fellow Kryptonians, Power Girl[136] (who is, in fact from the Krypton of the Earth-Two universe) and Mon-El,[137] have led to disappointment. The arrival of Supergirl, who has been confirmed to be not only from Krypton but also his cousin, has relieved this loneliness somewhat.[138] Superman's Fortress of Solitude acts as a place of solace for him in times of loneliness and despair.[139]

In Superman/Batman #3 (Dec. 2003), Batman, under writer Jeph Loeb, observes, "It is a remarkable dichotomy. In many ways, Clark is the most human of us all. Then ... he shoots fire from the skies, and it is difficult not to think of him as a god. And how fortunate we all are that it does not occur to 'him'." In writer Geoff Johns' Infinite Crisis #1 (Dec. 2005), part of the 2005–2006 "Infinite Crisis" crossover storyline, Batman admonishes him for identifying with humanity too much and failing to provide the strong leadership that superhumans need.

Age and birthday

Superman's age has varied through his history in comics. His age was originally left undefined, with real-time references to specific years sometimes given to past events in Golden Age and early Silver Age comics. In comics published between the early 1970s and early 1990s, his age was usually cited as 29 years old.[140] However, during "The Death of Superman" storyline, Clark's age was given as 34 years old (in a fictional promotional newspaper published), while 1994's "Zero Hour" timeline established his age as 35.

Action Comics #149 (Oct. 1950) gives October as Superman's birthdate. Comics of the 1960s through 1980s describe Superman's birthday as February 29.[141] Clark Kent, meanwhile, would celebrate his birthday on June 18, the date the Kents first found Clark; June 18 is also the birthdate of Superman voice actor Bud Collyer.[142] Following the 1980s editorial-revamp DC called Crisis on Infinite Earths, Kent's birthday is given as February 29.[143] Superman: Secret Origin #1 (Nov. 2009) depicts Kent celebrating his birthday on December 1.

Other versions

The details Superman's story vary across his large body of fiction published since 1938. Versions of Superman depicted on television and in movies are typically not part of the same narrative continuity presented in the comics, and even in the comic books there are many different depictions of the character, a few of which differ radically from the "classic" version (e.g., the graphic novel Superman: Red Son depicts a Communist Superman who rules the Soviet Union). DC Comics has on some occasions published crossover stories where different depictions of Superman interact with each other using the plot device of parallel universes. For instance, in the 1960s, the Superman of "Earth-One" would occasionally star in stories alongside the Superman of "Earth-Two", the latter of whom resembled Superman as he was portrayed in the 1940s. DC Comics has not developed a consistent and universal system to classify all versions of the character.

Powers and abilities

As an influential archetype of the superhero genre, Superman possesses extraordinary powers, with the character traditionally described as "Faster than a speeding bullet. More powerful than a locomotive. Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound ... It's Superman!",[144] a phrase coined by Jay Morton and first used in the Superman radio serials and Max Fleischer animated shorts of the 1940s[145] as well as the TV series of the 1950s. For most of his existence, Superman's famous arsenal of powers has included flight, super-strength, invulnerability to non-magical attacks, super-speed, vision powers (including x-ray, heat-emitting, telescopic, infra-red, and microscopic vision), super-hearing, super-intelligence, and super-breath, which enables him to blow out air at freezing temperatures, as well as exert the propulsive force of high-speed winds.[146]

As originally conceived and presented in his early stories, Superman's powers were relatively limited, consisting of superhuman strength that allowed him to lift a car over his head, run at amazing speeds and leap one-eighth of a mile, as well as an incredibly dense body structure that could be pierced by nothing less than an exploding artillery shell.[146] Siegel and Shuster compared his strength and leaping abilities to an ant and a grasshopper.[147] When making the Superman cartoons in the early 1940s, the Fleischer Brothers found it difficult to keep animating him leaping and requested to DC to change his ability to flying; this was an especially convenient concept for short films, which would have otherwise had to waste precious running time moving earthbound Clark Kent from place to place.[148] Writers gradually increased his powers to larger extents during the Silver Age, in which Superman could fly to other worlds and galaxies and even across universes with relative ease.[146] He would often fly across the solar system to stop meteors from hitting the Earth or sometimes just to clear his head. Writers found it increasingly difficult to write Superman stories in which the character was believably challenged,[149] so DC made a series of attempts to rein the character in. The most significant attempt, John Byrne's 1986 rewrite, established several hard limits on his abilities: He barely survives a nuclear blast, and his space flights are limited by how long he can hold his breath.[150] Superman's power levels have again increased since then, with Superman eventually possessing enough strength to hurl mountains, withstand nuclear blasts with ease, fly into the sun unharmed, and survive in the vacuum of outer space without oxygen.

The source of Superman's powers has changed subtly over the course of his history. It was originally stated that Superman's abilities derived from his Kryptonian heritage, which made him eons more evolved than humans.[128] This was soon amended, with the source for the powers now based upon the establishment of Krypton's gravity as having been stronger than that of the Earth. This situation mirrors that of Edgar Rice Burroughs' John Carter. As Superman's powers increased, the implication that all Kryptonians had possessed the same abilities became problematic for writers, making it doubtful that a race of such beings could have been wiped out by something as trifling as an exploding planet. In part to counter this, the Superman writers established that Kryptonians, whose native star Rao had been red, possessed superpowers only under the light of a yellow sun.[151]

Superman is most vulnerable to green Kryptonite, mineral debris from Krypton transformed into radioactive material by the forces that destroyed the planet. Exposure to green Kryptonite radiation nullifies Superman's powers and immobilizes him with pain and nausea; prolonged exposure will eventually kill him. The only substance on Earth that can protect him from Kryptonite is lead, which blocks the radiation. Lead is also the only known substance that Superman cannot see through with his x-ray vision. Kryptonite was introduced in 1943 as a plot device to allow the radio-serial voice actor, Bud Collyer, to take some time off.[152] Although green Kryptonite is the most commonly seen form, writers have introduced other forms over the years: such as red, gold, blue, white, and black, each with its own effect.[153]

Supporting characters

Clark Kent, Superman's secret identity, was based partly on Harold Lloyd and named after Clark Gable and Kent Taylor.[154][155] Creators have discussed the idea of whether Superman pretends to be Clark Kent or vice versa, and at differing times in the publication either approach has been adopted.[156][157] Although typically a newspaper reporter, during the 1970s the character left the Daily Planet for a time to work for television,[157] whilst the 1980s revamp by John Byrne saw the character become somewhat more aggressive.[150] This aggressiveness has since faded with subsequent creators restoring the mild mannerisms traditional to the character.

Allies

Superman's large cast of supporting characters includes Lois Lane, the character most commonly associated with Superman, being portrayed at different times as his colleague, competitor, love interest and wife. Other main supporting characters include Daily Planet coworkers such as photographer Jimmy Olsen and editor Perry White, Clark Kent's adoptive parents Jonathan and Martha Kent, childhood sweetheart Lana Lang and best friend Pete Ross, associates like Professor Hamilton and John Henry Irons who often provide scientific advice and tech support, and former college love interest Lori Lemaris (a mermaid). Stories making reference to the possibility of Superman siring children have been featured both in and out of mainstream continuity.

Incarnations of Supergirl, Krypto the Superdog, and Superboy have also been major characters in the mythos, as well as the Justice League of America (of which Superman is usually a member and often its leader). A feature shared by several supporting characters is alliterative names, especially with the initials "LL", including Lex Luthor, Lois Lane, Linda Lee, Lana Lang, Lori Lemaris, and Lucy Lane,[158] alliteration being common in early comics.

Team-ups with fellow comics icon Batman are common, inspiring many stories over the years. When paired, they are often referred to as the "World's Finest" in a nod to the name of the comic book series that features many team-up stories. In 2003, DC began to publish a new series featuring the two characters titled Superman/Batman or Batman/Superman. Following DC Comic's The New 52 line-wide relaunch, Superman established a romantic relationship with Wonder Woman. A comic book series titled Superman/Wonder Woman debuted in 2013, which explores their relationship and shared adventures.

Enemies

The villains Superman faced in the earliest stories were ordinary humans, such as gangsters, corrupt politicians, and violent husbands, but they soon grew more outlandish. The mad scientist Ultra-Humanite, introduced in Action Comics #13 (June 1939), was Superman's first recurring villain. The hero's best-known nemesis, Lex Luthor, was introduced in Action Comics #23 (April 1940) and has been envisioned over the years as both a recluse with advanced weaponry to a power-mad billionaire.[159] In 1944, the magical imp Mister Mxyzptlk, Superman's first recurring super-powered adversary, was introduced.[160] Superman's first alien villain, Brainiac, debuted in Action Comics #242 (July 1958). The monstrous Doomsday, introduced in Superman: The Man of Steel #17-18 (Nov.-Dec. 1992), was the first villain to evidently kill Superman in physical combat. Other adversaries include the odd Superman-doppelgänger Bizarro, and the Kryptonian criminal General Zod.[161]

Cultural impact

Superman has come to be seen as an American cultural icon.[162][163] Superman is often thought of as the first superhero. This point is debated by historians: Doctor Occult, an earlier creation of Siegel and Shuster, appeared in comic books two years before, and in newspaper comics there was the Phantom and Mandrake the Magician. But it was Superman that started the 20th century's craze for costumed adventurers.

His adventures and popularity have established the character as an inspiring force within the public eye, with the character serving as inspiration for musicians, comedians and writers alike. Kryptonite, Brainiac and Bizarro have become synonymous in popular vernacular with Achilles' heel, extreme intelligence[164] and reversed logic[165] respectively. Similarly, the phrase "I'm not Superman" or "you're not Superman" is an idiom used to suggest a lack of omnipotence.[166][167][168]

Merchandising

Superman became popular very quickly, with an additional title, Superman Quarterly, rapidly added. In 1940 the character was represented in the annual Macy's parade for the first time.[169] In fact Superman had become popular to the extent that in 1942, with sales of the character's three titles standing at a combined total of over 1.5 million, Time was reporting that "the Navy Department (had) ruled that Superman comic books should be included among essential supplies destined for the Marine garrison at Midway Islands."[170] The character was soon licensed by companies keen to cash in on this success through merchandising. The earliest paraphernalia appeared in 1939, a button proclaiming membership in the Supermen of America club. By 1940 the amount of merchandise available increased dramatically, with jigsaw puzzles, paper dolls, bubble gum and trading cards available, as well as wooden or metal figures. The popularity of such merchandise increased when Superman was licensed to appear in other media, and Les Daniels has written that this represents "the start of the process that media moguls of later decades would describe as 'synergy.'"[171] By the release of Superman Returns, Warner Bros. had arranged a cross promotion with Burger King,[172] and licensed many other products for sale.

Superman's appeal to licensees rests upon the character's continuing popularity, cross market appeal and the status of the "S" shield, the stylized magenta and gold "S" emblem Superman wears on his chest, as a fashion symbol.[173][174] The "S" shield by itself is often used in media to symbolize the Superman character.[175][176]

In other media

The character of Superman has appeared in various media aside from comic books, including radio and television series, several films, and video games. The first adaptation was a daily newspaper comic strip, launched on January 16, 1939, and running through May 1966; Siegel and Shuster used the first strips to establish Superman's background, adding details such as the planet Krypton and Superman's father, Jor-El, concepts not yet established in the comic books.[128] A radio show, The Adventures of Superman, premiered February 12, 1940, and featured the voice of Bud Collyer as Superman. It ran through 1951. Collyer was also cast as the voice of Superman in Paramount Pictures' 17 Superman animated cartoons produced by Fleischer Studios and then Famous Studios for theatrical release in 1941–1943. Early episodes each had a budget of $50,000[177] ($805,800 when adjusted for inflation), which was exceptional for the time.[178] The first live-action film was a 15-part serial released in 1948.

In 1948, the movie serial Superman made Kirk Alyn the first actor to portray the hero onscreen. The first feature film, Superman and the Mole Men, starring George Reeves, was released in 1951, and was intended to promote the first television series Adventures of Superman, which aired from 1952 to 1958. National had creative control over the show.[179] Television series featuring Superman and Superboy would also debut in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. In 1966 came the Broadway musical It's a Bird...It's a Plane...It's Superman, remade for television in 1975. Also in 1966, Superman starred in the first of several animated television series The New Adventures of Superman.

Superman returned to movie theaters in 1978 with director Richard Donner's Superman, starring Christopher Reeve, which spawned three sequels and was the most successful Superman feature film.[180] DC Comics has had little creative control over these in movies: When Warner Bros. sold the movie rights to Superman to the Salkinds in 1974, it demanded control over the budget and the casting but left everything else to the producers' discretion.[181]

In 2006, Bryan Singer directed the feature Superman Returns, starring Brandon Routh. In 2013, director Zack Snyder rebooted the film franchise with Man of Steel, starring Henry Cavill. Snyder also directed its 2016 sequel, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, which featured Superman alongside Batman and Wonder Woman for the first time in a live-action movie. Cavill will reprise his role as Superman in the 2017 film Justice League. Tyler Hoechlin is set to play Superman in the second season of the Supergirl TV series.[182]

Musical references, parodies, and homages

Superman has also featured as an inspiration for musicians, with songs by numerous artists from several generations celebrating the character. Donovan's Billboard Hot 100 topping single "Sunshine Superman" utilized the character in both the title and the lyric, declaring "Superman and Green Lantern ain't got nothing on me."[183] Folk singer/songwriter Jim Croce sung about the character in a list of warnings in the chorus of his song "You Don't Mess Around with Jim", introducing the phrase "you don't tug on Superman's cape" into popular lexicon.[184] Other tracks to reference the character include Genesis' "Land of Confusion",[185] the video to which featured a Spitting Image puppet of Ronald Reagan dressed as Superman,[186] "(Wish I Could Fly Like) Superman" by The Kinks on their 1979 album Low Budget and "Superman" by The Clique, a track later covered by R.E.M. on its 1986 album Lifes Rich Pageant. This cover is referenced by Grant Morrison in Animal Man, in which Superman meets the character, and the track comes on Animal Man's Walkman immediately after.[187] Crash Test Dummies' "Superman's Song", from the 1991 album The Ghosts That Haunt Me explores the isolation and commitment inherent in Superman's life.[188] Five for Fighting released "Superman (It's Not Easy)" in 2000, which is from Superman's point of view, although Superman is never mentioned by name.[189] From 1988 to 1993, American composer Michael Daugherty composed "Metropolis Symphony", a five-movement orchestral work inspired by Superman comics.[190][191]

Parodies of Superman did not take long to appear, with Mighty Mouse introduced in "The Mouse of Tomorrow" animated short in 1942.[192] While the character swiftly took on a life of its own, moving beyond parody, other animated characters soon took their turn to parody the character. In 1943, Bugs Bunny was featured in a short, Super-Rabbit, which sees the character gaining powers through eating fortified carrots. This short ends with Bugs stepping into a phone booth to change into a real "Superman" and emerging as a U.S. Marine. In 1956 Daffy Duck assumes the mantle of "Cluck Trent" in the short "Stupor Duck", a role later reprised in various issues of the Looney Tunes comic book.[193] In the United Kingdom Monty Python created the character Bicycle Repairman, who fixes bicycles on a world full of Supermen, for a sketch in series of their BBC show.[194] Also on the BBC was the sitcom My Hero, which presented Thermoman as a slightly dense Superman pastiche, attempting to save the world and pursue romantic aspirations.[195] In the United States, Saturday Night Live has often parodied the figure, with Margot Kidder reprising her role as Lois Lane in a 1979 episode. The manga and anime series Dr. Slump featured the character Suppaman; a short, fat, pompous man who changes into a thinly veiled Superman-like alter-ego by eating a sour-tasting umeboshi. Jerry Seinfeld, a noted Superman fan, filled his series Seinfeld with references to the character and in 1997 asked for Superman to co-star with him in a commercial for American Express. The commercial aired during the 1998 NFL Playoffs and Super Bowl, Superman animated in the style of artist Curt Swan, again at the request of Seinfeld.[196] In January 2013, Superman was featured in ScrewAttack's web series Death Battle, where he fought a hypothetical battle with the character Son Goku and won. A rematch was staged in July 2015, with Superman winning again. Superman was voiced during the battle simulations by the voice actor ItsJustSomeRandomGuy.[197]

Superman has also been used as reference point for writers, with Steven T. Seagle's graphic novel Superman: It's a Bird exploring Seagle's feelings on his own mortality as he struggles to develop a story for a Superman tale.[198] Brad Fraser used the character as a reference point for his play Poor Super Man, with The Independent noting the central character, a gay man who has lost many friends to AIDS as someone who "identifies all the more keenly with Superman's alien-amid-deceptive-lookalikes status."[199] Superman's image was also used in an AIDS awareness campaign by French organization AIDES. Superman was depicted as emaciated and breathing from an oxygen tank, demonstrating that no-one is beyond the reach of the disease, and it can destroy the lives of everyone.[200]

Superman is also mentioned in several films, including Joel Schumacher's Batman & Robin, in which Batman states, "That's why Superman works alone ..." in reference to the many troubles caused by his partner Robin, and also in Sam Raimi's Spider-Man, in which Aunt May gives her nephew Peter Parker a word of advice not to strain himself too much because, "You're not Superman, you know", among many others.

Literary analysis

Superman has been interpreted and discussed in many forms in the years since his debut. The character's status as the first costumed superhero has allowed him to be used in many studies discussing the genre, Umberto Eco noting that "he can be seen as the representative of all his similars".[201] Writing in Time in 1971, Gerald Clarke stated: "Superman's enormous popularity might be looked upon as signalling the beginning of the end for the Horatio Alger myth of the self-made man." Clarke viewed the comics characters as having to continuously update in order to maintain relevance, and thus representing the mood of the nation. He regarded Superman's character in the early seventies as a comment on the modern world, which he saw as a place in which "only the man with superpowers can survive and prosper."[202] Andrew Arnold, writing in the early 21st century, has noted Superman's partial role in exploring assimilation, the character's alien status allowing the reader to explore attempts to fit in on a somewhat superficial level.

A.C. Grayling, writing in The Spectator, traces Superman's stances through the decades, from his 1930s campaign against crime being relevant to a nation under the influence of Al Capone, through the 1940s and World War II, a period in which Superman helped sell war bonds,[203] and into the 1950s, where Superman explored the new technological threats. Grayling notes the period after the Cold War as being one where "matters become merely personal: the task of pitting his brawn against the brains of Lex Luthor and Brainiac appeared to be independent of bigger questions", and discusses events post 9/11, stating that as a nation "caught between the terrifying George W. Bush and the terrorist Osama bin Laden, America is in earnest need of a Saviour for everything from the minor inconveniences to the major horrors of world catastrophe. And here he is, the down-home clean-cut boy in the blue tights and red cape".[204]

An influence on early Superman stories is the context of the Great Depression. The left-leaning perspective of creators Shuster and Siegel is reflected in early storylines. Superman took on the role of social activist, fighting crooked businessmen and politicians and demolishing run-down tenements.[127] Comics scholar Roger Sabin sees this as a reflection of "the liberal idealism of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal", with Shuster and Siegel initially portraying Superman as champion to a variety of social causes.[50][205] In later Superman radio programs the character continued to take on such issues, tackling a version of the Ku Klux Klan in a 1946 broadcast, as well as combating anti-semitism and veteran discrimination.[206][207][208]

Scott Bukatman has discussed Superman, and the superhero in general, noting the ways in which they humanize large urban areas through their use of the space, especially in Superman's ability to soar over the large skyscrapers of Metropolis. He writes that the character "represented, in 1938, a kind of Corbusierian ideal. Superman has X-ray vision: walls become permeable, transparent. Through his benign, controlled authority, Superman renders the city open, modernist and democratic; he furthers a sense that Le Corbusier described in 1925, namely, that 'Everything is known to us'."[209]

Jules Feiffer has argued that Superman's real innovation lay in the creation of the Clark Kent persona, noting that what "made Superman extraordinary was his point of origin: Clark Kent." Feiffer develops the theme to establish Superman's popularity in simple wish fulfillment,[210] a point Siegel and Shuster themselves supported, Siegel commenting that "If you're interested in what made Superman what it is, here's one of the keys to what made it universally acceptable. Joe and I had certain inhibitions ... which led to wish-fulfillment which we expressed through our interest in science fiction and our comic strip. That's where the dual-identity concept came from" and Shuster supporting that as being "why so many people could relate to it".[211]

Ian Gordon suggests that the many incarnations of Superman across media use nostalgia to link the character to an ideology of the American Way. He defines this ideology as a means of associating individualism, consumerism, and democracy and as something that took shape around WWII and underpinned the war effort. Superman he notes was very much part of that effort.[212]

Superman's immigrant status is a key aspect of his appeal.[213][214][215] Aldo Regalado saw the character as pushing the boundaries of acceptance in America. The extraterrestrial origin was seen by Regalado as challenging the notion that Anglo-Saxon ancestry was the source of all might.[216] Gary Engle saw the "myth of Superman [asserting] with total confidence and a childlike innocence the value of the immigrant in American culture." He argues that Superman allowed the superhero genre to take over from the Western as the expression of immigrant sensibilities. Through the use of a dual identity, Superman allowed immigrants to identify with both their cultures. Clark Kent represents the assimilated individual, allowing Superman to express the immigrants cultural heritage for the greater good.[214] David Jenemann has offered a contrasting view. He argues that Superman's early stories portray a threat: "the possibility that the exile would overwhelm the country."[217] David Rooney, a theater critic for The New York Times, in his evaluation of the play, Year Zero, considers Superman to be the "quintessential immigrant story ... (b)orn on an alien planet, he grows stronger on Earth but maintains a secret identity tied to a homeland that continues to exert a powerful hold on him even as his every contact with those origins does him harm."[218]

Some see Judaic themes in Superman. Simcha Weinstein notes that Superman's story has some parallels to that of Moses. For example, Moses as a baby was sent away by his parents in a reed basket to escape death and adopted by a foreign culture. Weinstein also posits that Superman's Kryptonian name, "Kal-El", resembles the Hebrew words קל-אל, which can be taken to mean "voice of God".[219] Larry Tye suggests that this "Voice of God" is an allusion to Moses' role as a prophet.[220] The suffix "el", meaning "(of) God", is also found in the name of angels (e.g. Gabriel, Ariel), who are airborne humanoid agents of good with superhuman powers. The Nazis also thought Superman was a Jew and in 1940 Joseph Goebbels publicly denounced Superman and his creator Siegel.[221]

Superman stories have occasionally exhibited Christian themes as well. Screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz consciously made Superman an allegory for Christ in the 1978 movie starring Christopher Reeve:[222] baby Kal-El's ship resembles the Star of Bethlehem, and Jor-El's gives his son a messianic mission.

Critical reception and popularity

The character Superman and his various comic series have received various awards over the years.

- Superman placed first on IGN's Top 100 Comic Book Heroes.[223]

- Empire magazine named him the greatest comic book character.[224]

- The Reign of the Supermen is one of many storylines or works to have received a Comics Buyer's Guide Fan Award, winning the Favorite Comic Book Story category in 1993.[225]

- Superman came in at number 2 in VH1's Top Pop Culture Icons 2004.[226]

- Also in 2004, British moviegoers voted Superman the greatest superhero.[227]

- Works featuring the character have also garnered six Eisner Awards,[228][229] and three Harvey Awards,[230] either for the works themselves or the creators of the works.

- The Superman films have received a number of nominations and awards, with Christopher Reeve winning a BAFTA for his performance in Superman (1978).

- The Smallville television series has garnered Emmys for crew members and various other awards.[231][232][233]

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 Daniels 1998, p. 11

- ↑ Rhoades, Shirrel (2008). Comic Books: How the Industry Works. Peter Lang. p. 72. ISBN 0820488925.

- ↑ Holt, Douglas B. (2004). How Brands Become Icons: The Principles of Cultural Branding. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. p. 1. ISBN 1-57851-774-5.

- ↑ Koehler, Derek J.; Harvey, Nigel., eds. (2004). Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making. Blackwell. p. 519. ISBN 1-4051-0746-4.

- ↑ Dinerstein, Joel (2003). Swinging the machine: Modernity, technology, and African American culture between the wars. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 81. ISBN 1-55849-383-2.

- ↑ "Superman turns 75: Man of Steel milestone puts spotlight on creators' Cleveland roots". Daily News. New York City. The Associated Press. April 17, 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

'The encouragement that he received from his English teachers and the editors at the Glenville High School newspaper and the literary magazine gave my dad a real confidence in his talents,' [Laura Siegel Larson] said over the phone from Los Angeles.

- ↑ Daniels 1998, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Ricca (2014): "What really pushed Jerry in this direction was an article about comics called “The Funny Papers” that he read in Fortune magazine. The article begins with the shocking fact that “some twenty comic-strip headliners are paid at least $1,000 a week.” The article describes in detail how syndicates such as the Chicago Tribune and even Cleveland’s Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA) worked for writers and artists to put their strips into hundreds of papers. According to the article, this “is how the strips get into Big Money.” So much so that “the headliners usually get 50 per cent of the gross income.” [...] As far as artists go, “In many cases they were not artists at all, but just fellows with a knack for sketching who thought of a good idea or a funny character that ‘made a hit’ with an editor and eventually with newspaper readers.”"

- ↑ Ricca (2014), p. 92, says, "It was the night of Sunday, June 18, 1933". Siegel says only "early 1933" In Andrae (1983). Other sources, including court records, list the year as 1934.

- ↑ In Andrae (1983), Siegel is quoted as saying: "Obviously, having him a hero would be infinitely more commercial than having him a villain. I understand that the comic strip Dr. Fu Manchu ran into all sorts of difficulties because the main character was a villain. And with the example before us of Tarzan and other action heroes of fiction who were very successful, mainly because people admired them and looked up to them, it seemed the sensible thing to do to make The Superman a hero. The first piece was a short story, and that's one thing; but creating a successful comic strip with a character you'll hope will continue for many years, it would definitely be going in the wrong direction to make him a villain."

- ↑ Daniels (1998), p. 17: "... usually [Shuster] and Siegel agreed that no special costume was in evidence, and the surviving artwork bears them out. The most important point on which [Siegel and Shuster] are clear is that this version of the hero had no superpowers."

- ↑ In Andrae (1983), Shuster is quoted as saying: "It wasn't really Superman: that was before he evolved into a costumed figure. He was simply wearing a T-shirt and pants..."

- ↑ Humor Publishing Company at the Grand Comics Database.

- ↑ Dan Dunn at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on April 14, 2012.

- ↑ Jones (2004): A Humor comic starring the character Detective Dan "...wasn't much better than what he and Joe could do — but it was in print. And its publication didn't depend on the distant and indifferent world of newspaper syndication but on what was, in Jerry's mind at least, the far more familiar world of cheap magazines. 'We can do this!' he said."

- ↑ Most sources, including Jones (2004) and Ricca (2014), agree that Siegel met with Humor Publishing in Cleveland. Tye (2012) writes that they mailed their proposal to Humor's offices in Chicago.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ricca (2014)

- 1 2 Ricca (2014), p. 99: "Jerry was convinced, just as he was in those early pulp days, that you had to align yourself with someone famous to be famous yourself."

- ↑ Tye (2012): "'When I told Joe of this, he unhappily destroyed the drawn-up pages of "THE SUPERMAN" burning them in the furnace of his apartment building,' Jerry recalled. 'At my request, he gave me as a gift the torn cover.'"

- ↑ In an interview with Andrae (1983), Shuster said he destroyed their 1933 Superman comic as a reaction to Humor Publishing's rejection letter, which contradicts Siegel's account in Siegel's unpublished memoir. Tye (2012) argues that the account from the memoir is the truth, and that Shuster lied in the interview to avoid tension.

- 1 2 Jones (2004), p. 112-113

- ↑ Trexler, Jeff (August 20, 2008). "Superman's Hidden History: The Other "First" Artist". Newsarama.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ↑ "Scans of Siegel and Keaton's collaboration". Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2015.

- ↑ Ricca (2014), p. 102: "Jerry tried to sell this version to the syndicates, but no one was interested, so Keaton gave up."

- ↑ Daniels 1998, p. 18

- ↑ Wallace, Daniel; Bryan Singer (2006). The Art of Superman Returns. Chronicle Books. p. 22. ISBN 0-8118-5344-6.

- ↑ Over the years, Siegel and Shuster made contradictory statements regarding when they developed Superman's familiar costume. They occasionally claimed to have developed it immediately in 1933, but Daniels (1998) writes: "... usually [Shuster] and Siegel agreed that no special costume was in evidence [in 1933], and the surviving artwork bears them out." The cover art for their 1933 proposal to Humor Publishing shows a shirtless, cape-less Superman. Siegel's collaboration with Russell Keaton in 1934 contains no description or illustration of Superman in costume. Tye (2012) writes that Siegel and Shuster developed the costume shortly after they resumed working together. In an interview with Andrae (1983), Siegel said:

"NEMO: When you first conceived Superman, did you have the dual-identity theme in mind? Siegel: That occurred to me in late 1934, when I decided that I'd like to do Superman as a newspaper strip. I approached Joe about it, and he was enthusiastic about the possibility. I was up late one night, and more and more ideas kept coming to me, and I kept writing out several weeks of syndicate strips for the proposed newspaper strip. When morning came, I had written several weeks of material, and I dashed over to Joe's place and showed it to him. (This was the story that appeared in Action Comics #1, June, 1938, the first published appearance of Superman.) [...] Of course, Joe had worked on that earlier version of Superman, and when I came to him with this new version of it, he was immediately sold." - ↑ Siegel's unpublished memoir, The Story Behind Superman, as well as an interview in Nemo #2 in 1983, corroborate each other that Clark Kent's timid-journalist persona and Lois Lane were developed in 1934.

- ↑ Letter quoted in Ricca (2014), p. 146

- ↑ Ricca (2014), p. 134 "They submitted and resubmitted for several years."

- ↑ Siegel, Jerry. Unpublished memoir "The Story Behind Superman #1", registered for U.S. copyright in 1978 under later version Creation of a Superhero as noted by Tye (2012), p. 309. Memoir additionally cited by Ricca (2014), p. 148, and available online at sites including "The Story Behind Superman #1". Superman-Through-the-Ages.com. p. 5 of manuscript. Archived from the original on December 20, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ↑ Action Comics #1 (June 1938) at the Grand Comics Database.

- ↑ Daniels (1998), p. 17

- ↑ Ricca (2014): "The facts are that it was Harry [Donenfeld] who signed [Siegel and Shuster], at Gaines's direction, and when McClure sold the Superman strip to the newspapers, McClure bought the rights from Harry, not the boys. It was then Donenfeld who not only now owned the property, but received the lion's share of the profits; whatever Jerry and Joe got was parsed out by him."

- ↑ Kobler (1941), p. 73: "Before payment, however, [Donenfeld's] far-seeing general manager, Jack Liebowitz, mailed them a release form, explaining, ‘It is customary for all our contributors to release all rights to us. This is the businesslike way of doing things.’"

- ↑ Kobler (1941), p. 73: "The partners, who by this time had abandoned hope that Superman would ever amount to much, mulled this over gloomily. Then Siegel shrugged, ‘Well, at least this way we'll see him in print.’ They signed the form."

- ↑ Andrae (1983): "...when I did the version in 1934, (which years later, in 1938, was published, in revised form, in Action Comics #1) the John Carter stories did influence me. Carter was able to leap great distances because the planet Mars was smaller that the planet Earth; and he had great strength. I visualized the planet Krypton as a huge planet, much larger than Earth; so whoever came to Earth from that planet would be able to leap great distances and lift great weights."

- ↑ Steranko (1970), p. 37: "Wylie's story was one of Siegel's favorites; he even reviewed it in his S-F fanzine."

- ↑ Feeley, Gregory (March 2005). "When World-views Collide: Philip Wylie in the Twenty-first Century". Science Fiction Studies. 32 (95). ISSN 0091-7729. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2006.

- ↑ Jones (2004), p. 346: Wylie threatened to sue Siegel for plagiarism in 1940, but there is no evidence that he carried through with the litigation. Siegel flatly denied any plagiarism.

- 1 2 3 4 Andrae (1983)

- ↑ Andrae (1983): "... I was inspired by the movies. In the silent films, my hero was Douglas Fairbanks Senior, who was very agile and athletic. So I think he might have been an inspiration to us, even in his attitude. He had a stance which I often used in drawing Superman. You'll see in many of his roles—including Robin Hood—that he always stood with his hands on his hips and his feet spread apart, laughing—taking nothing seriously."

- 1 2 Best, Daniel (August 3, 2012). "'Jerry and I did a comic book together...' Jerry Siegel & Joe Shuster Interviewed". 20th Century Danny Boy. Archived from the original on December 4, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ↑ Siegel: "We especially loved some of those movies in which Harold Lloyd would start off as a sort of momma's boy being pushed around, kicked around, thrown around, and then suddenly would turn into a fighting whirlwind."

Shuster: "I was kind of mild-manned and wore glasses so I really identified with it"

Anthony Wall (1981). Superman - The Comic Strip Hero (Television production). BBC. Event occurs at 00:04:50. - ↑ Andrae (1983): Siegel: “As a high school student, I thought that some day I might become a reporter, and I had crushes on several attractive girls who either didn't know I existed or didn't care I existed. [...] It occurred to me: What if I was real terrific? What if I had something special going for me, like jumping over buildings or throwing cars around or something like that? Then maybe they would notice me.”

- ↑ Andrae (1983): "I also had classical heroes and strongmen in mind, and this shows in the footwear. In the third version Superman wore sandals laced halfway up the calf. You can still see this on the cover of Action #1, though they were covered over in red to look like boots when the comic was printed."

- ↑ Ricca (2014): "What the boys did read were the magazines and papers where "superman" was a common word. Its usage was almost always preceded by "a." Most times the word was used to refer to an athlete or a politician."

- ↑ Flagg, Francis (Nov 11, 1931). "The Superman of Dr. Jukes". Wonder Stories. Gernsback.

- ↑ "His life work was one which called for the abilities of a superman, and Doc had been trained from the cradle, that he might have the strength to arise to any occasion."

-Robeson, Kenneth (September 1933). "The Lost Oasis". Doc Savage Magazine. Street & Smith. - 1 2 The Mythology of Superman (DVD). Warner Bros. 2006.

- ↑ Jacobson, Howard (March 5, 2005). "Up, Up and Oy Vey!". The Times. UK. p. 5.: "If Siegel and Shuster knew of Nietzsche's Ubermensch, they didn't say..."

- ↑ Muir, John Kenneth (July 2008). The Encyclopedia of Superheroes on Film and Television. McFarland & Co. p. 539. ISBN 978-0-7864-3755-9. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ Tye (2012): "Vendors had sold 130,000 comic books, or 64 percent of the print run. Anything over 50 percent constituted a success and guaranteed a profit. [...] Sales, meanwhile, continued to climb—to 136,000 for the second issue, 159,000 for the third, 190,000 for the fourth, and 197,000 for the fifth. Action No. 13, released on the first anniversary of the original, offered up 415,000 reasons to celebrate. National printed 725,000 copies of Action No. 16 and sold 625,000—an unheard-of success rate of 86 percent."

- ↑ Tye (2012): "...readers were asked to list in order of preference their five favorite stories. [...] 404 of 542 respondents named Superman as tops, with 59 more listing him second.

- ↑ Superman #1 (Summer 1939) at the Grand Comics Database.

- ↑ Action Comics at the Grand Comics Database.

- ↑ Superman (1939-1986 series)] and Adventures of Superman (1987 continuation of series) at the Grand Comics Database.

- ↑ "Superman"-titled comics at the Grand Comics Database.

- ↑ "Marvel and DC sales figures".

- ↑ Miller, John Jackson, ed. "Superman Annual Sales Figures". ComicChron.com.

- ↑ Tye (2012): "Superman 75, the death issue, tallied the biggest one-day sale ever for a comic book, with more than six million copies printed."

- ↑ Tye (2012): "Journalists, along with most of their readers and viewers, didn’t understand that heroes regularly perished in the comics and almost never stayed dead."

- ↑ "February 2016 Comic Book Sales Figures". Comichron. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- ↑ Tye (2012): "The remaining audience [by 2011] was dedicated to the point of fanaticism, a trend that was self-reinforcing. No longer did casual readers pick up a comic at the drugstore or grocery, both because the books increasingly required an insider’s knowledge to follow the action and because they simply weren’t being sold anymore at markets, pharmacies, or even the few newsstands that were left. [...] Comic books had gone from being a cultural emblem to a countercultural refuge."

- ↑ Tumey, Paul (April 14, 2014). "Reviews: Superman: The Golden Age Sundays 1943-1946". The Comics Journal. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

...Jerry Siegel had his hands — and typewriter — full, turning out stories for the comic books and the daily newspaper strips (which had completely separate continuities from the Sundays).

- ↑ Daniels (1998), p. 74

- ↑ Cole, Neil A. (ed.). "Wayne Boring (1905 - 1987)". SupermanSuperSite.com. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ↑ Cole, Neil A. (ed.). "Win Mortimer (1919 - 1998)". SupermanSuperSite.com. Archived from the original on June 30, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Younis, Steven, ed. "Superman Newspaper Strips". SupermanHomepage.com. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- 1 2 Eury (2006), p. 18: "In 1948 Boring succeeded Shuster as the principal superman artist, his art style epitomizing the Man of Steel's comics and merchandising look throughout the 1950s."

- 1 2 Daniels (1998), p. 74: "...Superman was drawn in a more detailed, realistic style of illustration. He also looked bigger and stronger. "Until then Superman had always seemed squat," Boring said. "He was six heads high, a bit shorter than normal. I made him taller—nine heads high—but kept his massive chest."

- 1 2 Curt Swan (1987). Drawing Superman. Essay reprinted in Eury (2006), pp. 58: "For 30 years or so, from around 1955 until a couple of years ago when I more or less retired, I was the principal artists of the Superman comic for DC Comics."

- ↑ Tye (2012): "Initially Harry [Donenfeld], Jack [Liebowitz], and the managers they hired to oversee their growing editorial empire had let Jerry [Siegel] do as he wished with the character..."

- ↑ Tye (2012): "Neither Harry [Donenfeld] nor Jack [Liebowitz] had planned for a separate Superman comic book, or for that to be ongoing. Having Superman's story play out across different venues presented a challenge for Jerry [Siegel] and the writers who came after him: Each installment needed to seem original yet part of a whole, stylistically and narratively. Their solution, at the beginning, was to wing it..."

- ↑ Daniels (1998), p. 42: "...the publisher was anxious to avoid any repetition of the censorship problems associated with his early pulp magazines (such as the lurid Spicy Detective)."

- ↑ Tye (2012): "Once Superman became big business, however, plots had to be sent to New York for vetting. Not only did editors tell Jerry to cut out the guns and knives and cut back on social crusading, they started calling the shots on minute details of script and drawing."

- ↑ Daniels (1998), p. 42: "It was left to Ellsworth to impose tight editorial controls on Jerry Siegel. Henceforth, Superman would be forbidden to use his powers to kill anyone, even a villain."

- ↑ Tye (2012): "No hint of sex. No alienating parents or teachers. Evil geniuses like the Ultra-Humanite were too otherworldly to give kids nightmares."

[...]

"The Prankster, the Toyman, the Puzzler, and J. Wilbur Wolngham, a W. C. Fields lookalike, used tricks and gags instead of a bow and arrows in their bids to conquer Superman. For editors wary of controversy, 1940s villains like those were a way to avoid the sharp edges of the real world." - ↑ Tye (2012): "Before Mort came along, Superman’s world was ad hoc and seat-of-the-pants, with Jerry and other writers adding elements as they went along without any planning or anyone worrying whether it all hung together. That worked fine when all the books centered around Superman and all the writing was done by a small stable. Now the pool of writers had grown and there were eight different comic books with hundreds of Superman stories a year to worry about."

- ↑ Tye (2012): "But Weisinger’s innovations were taking a quiet toll on the story. Superman’s world had become so complicated that readers needed a map or even an encyclopedia to keep track of everyone and everything. (There would eventually be encyclopedias, two in fact, but the first did not appear until 1978.) All the plot complications were beguiling to devoted readers, who loved the challenge of keeping current, but to more casual fans they could be exhausting."

- ↑ Tye (2012): "Weisinger stories steered clear of the Vietnam War, the sexual revolution, the black power movement, and other issues that red the 1960s. There was none of what Mort would have called “touchy-feely” either, much as readers might have liked to know how Clark felt about his split personality, or whether Superman and Lois engaged in the battles between the sexes that were a hallmark of the era. Mort wanted his comics to be a haven for young readers, and he knew his right-leaning politics wouldn’t sit well with his leftist writers and many of his Superman fans."

- ↑ Daniels (1998), p. 102: "One of the ways the editor kept in touch with his young audience was through a letters colum, "Metropolis Mailbag," introduced in 1958."