Survivorship bias

Survivorship bias, or survival bias, is the logical error of concentrating on the people or things that "survived" some process and inadvertently overlooking those that did not because of their lack of visibility. This can lead to false conclusions in several different ways. The survivors may be actual people, as in a medical study, or could be companies or research subjects or applicants for a job, or anything that must make it past some selection process to be considered further.

Survivorship bias can lead to overly optimistic beliefs because failures are ignored, such as when companies that no longer exist are excluded from analyses of financial performance. It can also lead to the false belief that the successes in a group have some special property, rather than just coincidence. For example, if three of the five students with the best college grades went to the same high school, that can lead one to believe that the high school must offer an excellent education. This could be true, but the question cannot be answered without looking at the grades of all the other students from that high school, not just the ones who "survived" the top-five selection process.

Survivorship bias is a type of selection bias.

Examples

In finance and economics

In finance, survivorship bias is the tendency for failed companies to be excluded from performance studies because they no longer exist. It often causes the results of studies to skew higher because only companies which were successful enough to survive until the end of the period are included. For example, a mutual fund company's selection of funds today will include only those that are successful now. Many losing funds are closed and merged into other funds to hide poor performance. In theory, 90% of extant funds could truthfully claim to have performance in the first quartile of their peers, if the peer group includes funds that have closed.

In 1996, Elton, Gruber, and Blake showed that survivorship bias is larger in the small-fund sector than in large mutual funds (presumably because small funds have a high probability of folding).[1] They estimate the size of the bias across the U.S. mutual fund industry as 0.9% per annum, where the bias is defined and measured as:

- "Bias is defined as average α for surviving funds minus average α for all funds"

- (Where α is the risk-adjusted return over the S&P 500. This is the standard measure of mutual fund out-performance).

Additionally, in quantitative backtesting of market performance or other characteristics, survivorship bias is the use of a current index membership set rather than using the actual constituent changes over time. Consider a backtest to 1990 to find the average performance (total return) of S&P 500 members who have paid dividends within the previous year. To use the current 500 members only and create a historical equity line of the total return of the companies that met the criteria, would be adding survivorship bias to the results. S&P maintains an index of healthy companies, removing companies that no longer meet their criteria as a representative of the large-cap U.S. stock market. Companies that had healthy growth on their way to inclusion in the S&P 500, would be counted as if they were in the index during that growth period, when they were not. Instead there may have been another company in the index that was losing market capitalization and was destined for the S&P 600 Small-cap Index, that was later removed and would not be counted in the results. Using the actual membership of the index, applying entry and exit dates to gain the appropriate return during inclusion in the index, would allow for a bias-free output.

Michael Shermer in the Scientific American[2] and Larry Smith of the University of Waterloo[3] have described how advice about commercial success distorts perceptions of it, by ignoring all the businesses and college dropouts that failed.[4] Journalist and author David McRaney observes that the "advice business is a monopoly run by survivors. When something becomes a non-survivor, it is either completely eliminated, or whatever voice it has is muted to zero".[5] Financial writer Nassim Taleb called the survivorship bias "silent evidence" in his book The Black Swan.

In media, movies, television, music, literature, and art

While difficult to quantify objectively, a common opinion is that music was better in the past. However, while listeners are exposed to a much greater quantity (and thus, presumably, subjective quality) of contemporary music, only the "best" music from one generation survives to be frequently replayed for the next generation, and this process becomes more selective with each generation. While quality of media is a subjective measure from person to person, popularity results from a population's average evaluation of the merits of the media. The more time that a particular piece of art or literature survives as relevant and popular in the general population, the more reliable the measure of quality becomes, because it must pass evaluations by changing and differing generations. All of the art or literature from the past that was not of sufficient quality is "lost" to time, and becomes hidden or invisible to the contemporary listener, reader, or viewer. The net effect is that, in general, a contemporary listener, reader, or viewer is only exposed to those works of past art that have met the highest standards of several preceding generations, while contemporary works or arts have not yet been similarly vetted and the listener, reader, or viewer will thus be exposed to a much higher percentage of poor or mediocre quality works.

In manufacturing and goods production

A commonly held opinion in many populations is that machinery, equipment, and goods manufactured in previous generations often is better built and lasts longer than similar contemporary items. (This perception is reflected in the common expression "They don't make 'em [them] like they used to") Again, because of the selective pressures of time and use, it is inevitable that only those items which were built to last will have survived into the present day. Therefore, most of the old machinery still seen functioning well in the present day must necessarily have been built to a standard of quality necessary to survive. All of the machinery, equipment, and goods that have failed over the intervening years are no longer visible to the general population as they have been junked, scrapped, recycled, or otherwise disposed of.

Though survivorship bias may explain a significant portion of the common perception that older manufacturing processes were more rigorous, there are other processes that may explain that perception (see: Planned obsolescence, Overengineering). Still, it is difficult to directly compare and determine whether manufacturing has become overall better or worse. Manufactured goods are constantly changing, the same items are rarely built for more than a single generation, and even the raw materials change from one era to the next. Capabilities and processes in materials science, technology, manufacturing, and testing have all advanced immensely since the 20th century, undoubtedly raising the potential for similar increases in durability, but pressures on production costs and time have also increased, resulting in manufacturing shortcuts that often result in less durable products. Overall, the contemporary consumer probably has access to and experiences a much wider variety of product durability than past generations. Again, bias arises from the fact that historical goods of poor quality are no longer visible, and only the best produced items of the past survive to today.

In architecture and construction

Just as new buildings are being built everyday and older structures are constantly torn down, the story of most civil and urban architecture involves a process of constant renewal, renovation, and revolution. Only the most (subjectively, but popularly-determined) beautiful, most useful, and most structurally sound buildings survive from one generation to the next. This creates another selection effect where the ugliest and weakest buildings of history have long been eradicated from existence and thus the public view, and so it leaves the visible impression, seemingly correct but factually flawed, that all buildings in the past were both more beautiful and better built.

In highly competitive careers

Whether it be movie stars, or athletes, or musicians, or CEOs of multi-billion dollar corporations who dropped out of school, popular media often tells the story of the determined individual who pursues their dreams and beats the odds. There is much less focus on the many people that may be similarly skilled and determined but fail to ever find success because of factors beyond their control or other (seemingly) random events.[6] This creates a false public perception that anyone can achieve great things if they have the ability and make the effort. The overwhelming majority of failures are not visible to the public eye, and only those who survive the selective pressures of their competitive environment are seen regularly.

In the military

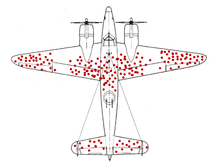

During World War II, the statistician Abraham Wald took survivorship bias into his calculations when considering how to minimize bomber losses to enemy fire. Researchers from the Center for Naval Analyses had conducted a study of the damage done to aircraft that had returned from missions, and had recommended that armor be added to the areas that showed the most damage. Wald noted that the study only considered the aircraft that had survived their missions—the bombers that had been shot down were not present for the damage assessment. The holes in the returning aircraft, then, represented areas where a bomber could take damage and still return home safely. Wald proposed that the Navy instead reinforce the areas where the returning aircraft were unscathed, since those were the areas that, if hit, would cause the plane to be lost.[7][8]

In cats

In a study performed in 1987 it was reported that cats who fall from less than six stories, and are still alive, have greater injuries than cats who fall from higher than six stories.[9][10] It has been proposed that this might happen because cats reach terminal velocity after righting themselves at about five stories, and after this point they relax, leading to less severe injuries in cats who have fallen from six or more stories.[11]

Another possible explanation for this phenomenon would be survivorship bias. Cats that die in falls are less likely to be brought to a veterinarian than injured cats, and thus many of the cats killed in falls from higher buildings are not reported in studies of the subject.[12]

As a general experimental flaw

Survivorship bias (or survivor bias) is a statistical artifact in applications outside finance, where studies on the remaining population are fallaciously compared with the historic average despite the survivors having unusual properties. Mostly, the unusual property in question is a track record of success (like the successful funds).

For example, the parapsychology researcher Joseph Banks Rhine believed he had identified the few individuals from hundreds of potential subjects who had powers of ESP. His calculations were based on the improbability of these few subjects guessing the Zener cards shown to a partner by chance.

A major criticism which surfaced against his calculations was the possibility of unconscious survivorship bias in subject selections. He was accused of failing to take into account the large effective size of his sample (all the people he rejected as not being "strong telepaths" because they failed at an earlier testing stage). Had he done this he might have seen that, from the large sample, one or two individuals would probably achieve the track record of success he had found purely by chance.

Writing about the Rhine case in Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science, Martin Gardner explained that he did not think the experimenters had made such obvious mistakes out of statistical naïveté, but as a result of subtly disregarding some poor subjects. He said that, without trickery of any kind, there would always be some people who had improbable success, if a large enough sample were taken. To illustrate this, he speculates about what would happen if one hundred professors of psychology read Rhine's work and decided to make their own tests; he said that survivor bias would winnow out the typical failed experiments, but encourage the lucky successes to continue testing. He thought that the common null hypothesis (of no result) would not be reported, but:

- "Eventually, one experimenter remains whose subject has made high scores for six or seven successive sessions. Neither experimenter nor subject is aware of the other ninety-nine projects, and so both have a strong delusion that ESP is operating."

He concludes:

- "The experimenter writes an enthusiastic paper, sends it to Rhine who publishes it in his magazine, and the readers are greatly impressed".

If enough scientists study a phenomenon, some will find statistically significant results by chance, and these are the experiments submitted for publication. Additionally, papers showing positive results may be more appealing to editors.[13] This problem is known as positive results bias, a type of publication bias. To combat this, some editors now call for the submission of "negative" scientific findings, where "nothing happened".

Survivorship bias is one of the issues discussed in the provocative 2005 paper "Why Most Published Research Findings Are False".[13]

In business law

Survivorship bias can raise truth-in-advertising problems when the success rate advertised for a product or service is measured with respect to a population whose makeup differs from that of the target audience whom the company offering that product or service targets with advertising claiming that success rate. These problems become especially significant when

- the advertisement either fails to disclose the existence of relevant differences between the two populations or describes them in insufficient detail;

- these differences result from the company's deliberate "pre-screening" of prospective customers to ensure that only customers with traits increasing their likelihood of success are allowed to purchase the product or service, especially when the company's selection procedures or evaluation standards are kept secret; and

- the company offering the product or service charges a fee, especially one that is non-refundable or not disclosed in the advertisement, for the privilege of attempting to become a customer.

For example, the advertisements of online dating service eHarmony.com pass this test because they fail the first two prongs but not the third: They claim a success rate significantly higher than that of competing services while generally not disclosing that the rate is calculated with respect to a viewership subset who possess traits that increase their likelihood of finding and maintaining relationships and lack traits that pose obstacles to their doing so (1), and the company deliberately selects for these traits by administering a lengthy pre-screening process designed to reject prospective customers who lack the former traits or possess the latter ones (2), but the company does not charge a fee for administration of its pre-screening test, with the effect that its prospective customers face no "downside risk" other than losing the time and expending the effort involved in completing the pre-screening process (negating 3).[14]

Similarly, many investors believe that chance is the main reason that most successful fund managers have the track records they do.

See also

- Attrition bias

- Cherry picking (fallacy)

- Econometrics

- Fooled by Randomness by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Meta-analysis

- Multiple comparisons problem

- Selection bias

- Selection principle

- Texas sharpshooter fallacy

References

- ↑ Elton; Gruber; Blake (1996). "Survivorship Bias and Mutual Fund Performance". Review of Financial Studies. 9 (4): 1097–1120. doi:10.1093/rfs/9.4.1097. In this paper the researchers eliminate survivorship bias by following the returns on all funds extant at the end of 1976. They show that other researchers have drawn spurious conclusions by failing to include the bias in regressions on fund performance.

- ↑ Michael Shermer (2014-08-19). "How the Survivor Bias Distorts Reality". Scientific American.

- ↑ Carmine Gallo (2012-12-07). "High-Tech Dropouts Misinterpret Steve Jobs' Advice". Forbes.

- ↑ Robert J Zimmer (2013-03-01). "The Myth of the Successful College Dropout: Why It Could Make Millions of Young Americans Poorer". The Atlantic.

- ↑ Karen E. Klein. "How Survivorship Bias Tricks Entrepreneurs". Bloomberg.

- ↑ Karen E. Klein (2014-08-11). "How Survivorship Bias Tricks Entrepreneurs". Bloomberg Business.

- ↑ Mangel, Marc; Samaniego, Francisco (June 1984). "Abraham Wald's work on aircraft survivability". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 79 (386): 259–267. doi:10.2307/2288257. JSTOR 2288257. Reprint on author's web site

- ↑ Wald, Abraham. (1943). A Method of Estimating Plane Vulnerability Based on Damage of Survivors. Statistical Research Group, Columbia University. CRC 432 — reprint from July 1980. Center for Naval Analyses.

- ↑ Whitney, WO; Mehlhaff, CJ (1987). "High-rise syndrome in cats". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 191 (11): 1399–403. PMID 3692980.

- ↑ Highrise Syndrome in Cats

- ↑ Falling Cats

- ↑ "Do cats always land unharmed on their feet, no matter how far they fall?". The Straight Dope. July 19, 1996. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- 1 2 Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2005). "Why Most Published Research Findings Are False". PLoS Med. 2 (8): e124. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. PMC 1182327

. PMID 16060722.

. PMID 16060722. - ↑ Farhi, Paul (May 13, 2007). "They Met Online, but Definitely Didn't Click". Washington Post.