Peganum harmala

| Peganum harmala | |

|---|---|

| |

| Harmal (Peganum harmala) flower | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Nitrariaceae |

| Genus: | Peganum |

| Species: | P. harmala |

| Binomial name | |

| Peganum harmala L.[1] | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Peganum harmala, commonly called esfand,[3] wild rue,[1] Syrian rue,[1] African rue,[1] harmel,[1] or aspand[4] (among other similar pronunciations and spellings), is a plant of the family Nitrariaceae. Its common English-language name came about because of a resemblance to rue (which is not related). The plant's seeds are especially noteworthy because they have seen continual use for thousands of years in the rites of many cultures.[5] The plant has remained a popular tool in both folk medicine and spiritual practices for so long that some historians believe the plant may be the ancient "soma"[6] (a medicinal aid that is mentioned in a variety of ancient Indo Iranian texts but whose exact identity has been lost to history).

It is a perennial plant which can grow to about 0.8 m tall,[7] but normally it is about 0.3 m tall.[8] The roots of the plant can reach a depth of up to 6.1 m, if the soil where it is growing is very dry.[8] It blossoms between June and August in the Northern Hemisphere.[9] The flowers are white and are about 2.5–3.8 cm in diameter.[9] The round seed capsules measure about 1–1.5 cm in diameter,[10] have three chambers and carry more than 50 seeds.[9]

Peganum harmala is of Asian Origin and grows in the Middle East and in part of South Asia mainly in India and Pakistan. It was first planted in the United States in 1928 in New Mexico by a farmer wanting to manufacture the dye "Iranian red" from its seeds.[8] Since then, it has spread invasively to Arizona, California, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Texas and Washington.[11] "Because it is so drought tolerant, African rue can displace the native saltbushes and grasses growing in the salt-desert shrub lands of the Western U.S."[8]

Traditional use

In Turkey, dried capsules from this plant are strung and hung in homes or vehicles to protect against "the evil eye".[5][12] It is widely used for protection against Djinn in Morocco (see Légey "Essai de Folklore marocain", 1926).

In Iran, and some countries in the Arab world such as, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Jordan , dried capsules mixed with other ingredients are placed onto red hot charcoal, where they explode with little popping noises in a way similar to American popcorn. When they burst a fragrant smoke is released. This smoke is wafted around the head of those afflicted by or exposed to the gaze of strangers while a specific prayer is recited. This tradition is still followed by members of many religions, including Christians, Muslims, and some Jews. Several versions of the prayer accompanying the ritual, the name of an ancient Zoroastrian Persian king, called Naqshaband, is used. He is said to have first learned the prayer from five protective female spirits, called Yazds.[5][12]

In Yemen, the Jewish custom of old was to bleach wheaten flour on Passover, in order to produce a clean and white unleavened bread. This was done by spreading whole wheat kernels upon a floor, and then spreading stratified layers of African rue (Peganum harmala) leaves upon the wheat kernels; a layer of wheat followed by a layer of Wild rue, which process was repeated until all wheat had been covered over with the astringent leaves of this plant. The wheat was left in this state for a few days, until the outer kernels of the wheat were bleached by the astringent vapors emitted by the Wild rue. Afterwards, the wheat was taken up and sifted, to rid them of the residue of leaves. They were then ground into flour, which left a clean and white batch of flour.[13]

Peganum harmala has been used to treat pain and to treat skin inflammations, including skin cancers.[14][15][16]

Peganum harmala has been used as an emmenagogue and abortifacient agent.[17][18]

The "root is applied to kill lice" and when burned, the seeds kill insects and inhibit the reproduction of the Tribolium castaneum beetle.[19]

It is also used as an anthelmintic (to expel parasitic worms). Reportedly, the ancient Greeks used the powdered seeds to get rid of tapeworms and to treat recurring fevers (possibly malaria).[20]

A red dye, "Turkey red",[21] from the seeds (but usually obtained from madder) is often used in western Asia to dye carpets. It is also used to dye wool. When the seeds are extracted with water, a yellow fluorescent dye is obtained.[22] If they are extracted with alcohol, a red dye is obtained.[22] The stems, roots and seeds can be used to make inks, stains and tattoos.[23]

Some scholars identify harmal with the entheogenic haoma of pre-Zoroastrian Persian religions.[6]

Research into other potential uses

Several scientific laboratories have studied possible uses for Peganum harmala through studies in laboratory animals (in vivo) and in cells (in vitro).

Fertility

In large quantities, it can reduce spermatogenesis and male fertility in rats.[24]

Antiprotozoal

Peganum harmala has been shown to have antibacterial and anti-protozoal activity,[25] including antibacterial activity against drug-resistant bacteria.[26]

One of the compounds found in P. harmala, vasicine (peganine), has been found to kill Leishmania donovani, a protozoan parasite that can cause potentially fatal visceral leishmaniasis.[27]

Another alkaloid, harmine, found in P. harmala, has appreciable efficacy in destroying intracellular parasites in the vesicular forms.[28]

A small study in sheep infected with the protozoal Theileria hirci found Peganum harmala extract to be an effective treatment.[29]

Anticancer

Seed extracts also show effectiveness against various tumor cell lines, both in vitro and in vivo.[15]

"The beta-carboline alkaloids present in medicinal plants, such as Peganum harmala and Eurycoma longifolia, have recently drawn attention due to their antitumor activities. Further mechanistic studies indicate that beta-carboline derivatives inhibit DNA topoisomerases and interfere with DNA synthesis."[30]

Peganum harmala has antioxidant and antimutagenic properties.[31] Both the plant and the extract harmine exhibit cytotoxicity with regards to HL60 and K562 leukemia cell lines.[32]

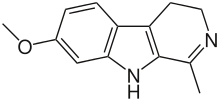

Alkaloids

Some alkaloids of harmal seeds are monoamine oxidase A inhibitors (MAOIs):[33]

- The coatings of the seeds are said to contain large amounts of harmine.[7]

- Total harmala alkaloids were at least 5.9% of dried weight, in one study.[34]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peganum harmala. |

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Peganum harmala information from NPGS/GRIN". Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ↑ "The Plant List: A Working List of all Plant Species".

- ↑ Mahmoud Omidsalar Esfand: a common weed found in Persia, Central Asia, and the adjacent areas. Encyclopedia Iranica Vol. VIII, Fasc. 6, pp. 583-584. Originally published: 15 December 1998. Online version last updated 19 January 2012

- ↑ "againsttheevileye". Lucky Mojo dot com.

- 1 2 3 "Herb Dictionary: apsand seed". Aunty Flo dot com herb-dictionary.

- 1 2 Karel van der Torn, ed., "Haoma," Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. (New York: E.J. Brill, 1995), 730.

- 1 2 "Peganum genus". www.cdfa.ca.gov. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- 1 2 3 4 Davison, Jay; Wargo, Mike (2001). Recognition and Control of African Rue in Nevada (PDF). University of Nevada, Reno. OCLC 50788872.

- 1 2 3 "Erowid Syrian Rue Vaults: Smoking Rue Extract / Harmala". www.erowid.org. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- ↑ "Lycaeum > Leda > Peganum harmala". leda.lycaeum.org. Archived from the original on 19 February 2007. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- ↑ "PLANTS Profile for Peganum harmala (harmal peganum) / USDA PLANTS". USDA. 2008-01-17. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- 1 2 "Esphand Against the Evil Eye in Zoroastrian Magic". Lucky Mojo dot com.

- ↑ Yiḥyah Salaḥ, Questions & Responsa Pe'ulath Ṣadiq, vol. I, responsum # 171, Jerusalem 1979; ibid., vol. III, responsum # 13 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Farouk L, Laroubi A, Aboufatima R, Benharref A, Chait A (February 2008). "Evaluation of the analgesic effect of alkaloid extract of Peganum harmala L.: possible mechanisms involved". J Ethnopharmacol. 115 (3): 449–54. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.014. PMID 18054186.

- 1 2 Lamchouri F, Settaf A, Cherrah Y, et al. (1999). "Antitumour principles from Peganum harmala seeds". Therapie. 54 (6): 753–8. PMID 10709452.

- ↑ Jinous Asgarpanah (2012). "Chemistry, pharmacology and medicinal properties of Peganum harmala L". African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 6 (22). doi:10.5897/AJPP11.876.

- ↑ Monsef, Hamid Reza; Ali Ghobadi; Mehrdad Iranshahi; Mohammad Abdollahi (19 February 2004). "Antinociceptive effects of Peganum harmala L. alkaloid extract on mouse formalin test" (PDF). J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 7 (1): 65–9. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- 1 2 3 http://www.thenook.org/archives/tek/06332ott.html[]

- ↑ Jbilou R, Amri H, Bouayad N, Ghailani N, Ennabili A, Sayah F (March 2008). "Insecticidal effects of extracts of seven plant species on larval development, alpha-amylase activity and offspring production of Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) (Insecta: Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae)". Bioresour. Technol. 99 (5): 959–64. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.03.017. PMID 17493805.

- ↑ Panda H (2000). Herbs Cultivation and Medicinal Uses. Delhi: National Institute Of Industrial Research. p. 435. ISBN 81-86623-46-9.

- ↑ Mabberley, D.J. (2008). Mabberley's Plant-book: A Portable Dictionary of Plants, Their Classifications, and Uses. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521820714.

- 1 2 "Mordants". www.fortlewis.edu. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 2014-10-28.

- ↑ "Aluka — Entry for Peganum harmala Linn. [family ZYGOPHYLLACEAE]". www.aluka.org. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ El-Dwairi QA, Banihani SM (June 2007). "Histo-functional effects of Peganum harmala on male rat's spermatogenesis and fertility". Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 28 (3): 305–10. PMID 17627267.

- ↑ Al-Shamma A, Drake S, Flynn DL, et al. (1981). "Antimicrobial agents from higher plants. Antimicrobial agents from Peganum harmala seeds". J. Nat. Prod. 44 (6): 745–7. doi:10.1021/np50018a025. PMID 7334386.

- ↑ Arshad N, Zitterl-Eglseer K, Hasnain S, Hess M (November 2008). "Effect of Peganum harmala or its beta-carboline alkaloids on certain antibiotic resistant strains of bacteria and protozoa from poultry". Phytother Res. 22 (11): 1533–8. doi:10.1002/ptr.2528. PMID 18814210.

- ↑ Misra P, Khaliq T, Dixit A, et al. (November 2008). "Antileishmanial activity mediated by apoptosis and structure-based target study of peganine hydrochloride dihydrate: an approach for rational drug design". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62 (5): 998–1002. doi:10.1093/jac/dkn319. PMID 18694906.

- ↑ Lala S, Pramanick S, Mukhopadhyay S, Bandyopadhyay S, Basu MK (April 2004). "Harmine: evaluation of its antileishmanial properties in various vesicular delivery systems". J Drug Target. 12 (3): 165–75. doi:10.1080/10611860410001712696. PMID 15203896.

- ↑ Derakhshanfar A, Mirzaei M (March 2008). "Effect of Peganum harmala (wild rue) extract on experimental ovine malignant theileriosis: pathological and parasitological findings". Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 75 (1): 67–72. doi:10.4102/ojvr.v75i1.90. PMID 18575066.

- ↑ Li Y, Liang F, Jiang W, et al. (August 2007). "DH334, a beta-carboline anti-cancer drug, inhibits the CDK activity of budding yeast". Cancer Biol. Ther. 6 (8): 1193–9. doi:10.4161/cbt.6.8.4382. PMID 17622795.

- ↑ Moura DJ, Richter MF, Boeira JM, Pêgas Henriques JA, Saffi J (July 2007). "Antioxidant properties of beta-carboline alkaloids are related to their antimutagenic and antigenotoxic activities". Mutagenesis. 22 (4): 293–302. doi:10.1093/mutage/gem016. PMID 17545209.

- ↑ Jahaniani F, Ebrahimi SA, Rahbar-Roshandel N, Mahmoudian M (July 2005). "Xanthomicrol is the main cytotoxic component of Dracocephalum kotschyii and a potential anti-cancer agent". Phytochemistry. 66 (13): 1581–92. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.04.035. PMID 15949825.

- ↑ Massaro, Edward J. (2002). Handbook of Neurotoxicology. Humana Press. p. 237. ISBN 0-89603-796-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hemmateenejad B, Abbaspour A, Maghami H, Miri R, Panjehshahin MR (August 2006). "Partial least squares-based multivariate spectral calibration method for simultaneous determination of beta-carboline derivatives in Peganum harmala seed extracts". Anal. Chim. Acta. 575 (2): 290–9. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2006.05.093. PMID 17723604.

- 1 2 3 4 Pulpati H, Biradar YS, Rajani M (2008). "High-performance thin-layer chromatography densitometric method for the quantification of harmine, harmaline, vasicine, and vasicinone in Peganum harmala". J AOAC Int. 91 (5): 1179–85. PMID 18980138.

- 1 2 3 4 Herraiz T, González D, Ancín-Azpilicueta C, Arán VJ, Guillén H (March 2010). "beta-Carboline alkaloids in Peganum harmala and inhibition of human monoamine oxidase (MAO)". Food Chem. Toxicol. 48 (3): 839–45. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2009.12.019. PMID 20036304.