Tablet weaving

Tablet Weaving (often card weaving in the United States) is a weaving technique where tablets or cards are used to create the shed through which the weft is passed. As the materials and tools are relatively cheap and easy to obtain, tablet weaving is popular with hobbyist weavers. Currently most tablet weavers produce narrow work such as belts, straps, or garment trims.

History

Tablet weaving is often erroneously believed to date back to pharaonic Egypt. This theory was advanced early in the twentieth century based on an elaborate ancient Egyptian belt of uncertain provenance often called the Girdle of Ramses because it bore an inked cartouche of Ramesses III. Arnold van Gennep and G. Jéquier published a book in 1916, Le tissage aux cartons et son utilisation décorative dans l'Égypte ancienne, predicated on the assumption that the ancient Egyptians were familiar with tablet weaving. Scholars argued spiritedly about the production method of the belt for decades. Many popular books on tablet weaving promoted the Egyptian origin theory until, in an appendix to his magisterial work on tablet weaving, Peter Collingwood proved by structural analysis that the linen belt couldn't have been woven on tablets. [1]

Tablet weaving does go back at least to the eighth century BCE in early Iron age Europe[2] where it is found in areas employing the warp-weighted loom.[3] Historically the technique served several purposes: to create starting and/or selvedge bands for larger textiles such as those produced on the warp-weighted loom; to weave decorative bands onto existing textiles;[4] and to create freestanding narrow work.

Early examples have been found at Hochdorf, Germany,[5] and Apremont, Haute-Saône, France,[6] as well as in Italy, Greece, and Austria.[2] Elaborate tablet-woven bands are found in many high status Iron Age and medieval graves of Europe as well as in the Roman period in the Near East. They are presumed to have been standard trim for garments among various European peoples, including the Vikings.[7] Many museum examples exist of such bands used on ecclesiastical textiles or as the foundation for elaborate belts in the European Middle Ages. In the seventeenth century tablet weaving was also used to produce some monumental silk hangings in Ethiopia.[8]

Tools for tablet weaving

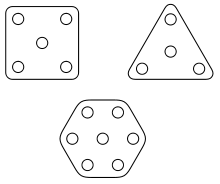

The tablets used in weaving are typically shaped as regular polygons, with holes near each vertex and possibly at the center, as well. The number of holes in the tablets used is a limiting factor on the complexity of the pattern woven. The corners of the tablets are typically rounded to prevent catching as they are rotated during weaving.

In the past, weavers made tablets from bark, wood, bone,[9] horn, stone, leather,[1] metal[10] or a variety of other materials. Modern cards are frequently made from cardboard. Some weavers even drill holes in a set of playing cards. This is an easy way to get customized tablets or large numbers of inexpensive tablets.

The tablets are usually marked with colors or stripes so that their facings and orientations can be easily noticed.

Procedure

The fundamental principle is to turn the tablets to lift selected sets of threads in the warp. The tablets may be turned in one direction continually as a pack, turned individually to create patterns, or turned some number of times "forward" and the same number "back". Twisting the tablets in only one direction can create a ribbon that curls in the direction of the twist, though there are ways to thread the tablets that mitigate this issue.

Traditionally, one end of the warp was tucked into, or wrapped around the weaver's belt, and the other is looped over a toe, or tied to a pole or furniture. Some traditional weavers weave between two poles, and wrap the weft around the poles. Commercial "tablet weaving looms" adapt this idea, and are convenient because they make it easy to put the work down.

Some modern weavers thread each card individually, but this is time consuming. The traditional threading method is to put all the threads through the holes of an entire deck. Then, starting at the pair of cards farthest from the bobbins, the threads are pulled from between each pair of cards out to the length of the warp, and hooked or tied on each end. If the cards remain "paired", so that alternate cards twist in opposite directions, continuous turning does not twist the ribbon. Some weavers in some patterns flip alternate cards, "unpairing" them. This makes it easier to turn individual cards.

A shuttle about twice as wide as the ribbon is placed in the shed to beat the previous weft, then carry the next weft into the shed. Shuttles made for tablet weaving have sharp edges to beat down the weft. The best shuttles have plates to cover the bobbin, and keep it from catching the warp. Simple flat wooden or plastic shuttles work well for weaving with large yarns, but weaving with finer threads goes more quickly with a tablet-weaving shuttle.

Patterns are made by placing different-colored yarns in different holes, then turning individual cards until the desired colors of the weft are on top. After that, a simple pattern, like a stripe, small diamond or check, can be repeated just by turning the deck of tablets.

Tablet weaving is especially freeing, because any pattern can be created by turning individual tablets. This is in contrast to normal looms, in which the complexity of the pattern is limited by the number of shafts available to lift threads, and the threading of the heddles.

Tablet weaving can also be used to weave tubes or double weave. The tablets are made to have four levels in the warp, and then two sheds are beat and wefted, one in the top pair of warps, and the other in the bottom pair, before turning the deck. Since groups of tablets can be turned separately, the length, width and joining of the tubes can be controlled by the weaver.

See also

References

- 1 2 Collingwood, P. 1982. The Techniques of Tablet Weaving (London: Faber and Faber)

- 1 2 Gleba, Margarita (2008). Textile Production in Pre-Roman Italy. Oxford: Ancient Textiles Series, Vol. 4, Oxbow Books. p. 138-139. ISBN 978-1-84217-330-5.

- ↑ Priest-Dorman, Carolyn. ""Scutulis Dividere Gallia": Weaving on Tablets in Western Europe". DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Textile Society of America Proceedings, 1998. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ Ræder Knudsen, L. 1998. "An Iron Age Cloak with Tablet-woven Borders: a New Interpretation of the Method of Production." In Textiles in European Archaeology: Report from the 6th NESAT Symposium, pp. 79-84.

- ↑ Ræder Knudsen, L. 1994. "Analysis and Reconstruction of Two Tablet Woven Bands from the Celtic Burial Hochdorf." In North European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles 5, pp. 53 - 60.

- ↑ Barber, E.J.W. 1992. Prehistoric Textiles Princeton University Press.

- ↑ e.g. Rasmussen, L., and Lönborg, B. 1993. "Dragtrester i grav ACQ, Köstrup." Fynske Minder (Odense bys Museer), pp. 175-182.

- ↑ Gervers, Michael. "The tablet-woven hangings of Tigre, Ethiopia: from history to symmetry" (PDF). Treasury of Ethiopian Images. The Burlington Magazine, 2004.

- ↑ MacGregor, Arthur 1985. Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn: The Technology of Skeletal Materials since the Roman Period. (London: Croom Helm)

- ↑ Götze, A., 1908. "Brettchenweberei im Altertum," Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, Vol. 40.