Tactical nuclear weapon

A tactical nuclear weapon (or TNW) also known as non-strategic nuclear weapon[1] refers to a nuclear weapon which is designed to be used on a battlefield in military situations, mostly with friendly forces in proximity and perhaps even on contested friendly territory. This is opposed to strategic nuclear weapons which are designed to be mostly targeted in the enemy interior away from the war front against military bases, cities, towns, arms industries, and other hardened or larger-area targets to damage the enemy's ability to wage war. Tactical nuclear weapons were a large part of the peak nuclear weapons stockpile levels during the Cold War.

Types

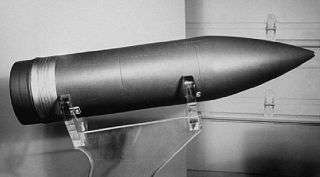

Tactical nuclear weapons include not only gravity bombs and short-range missiles, but also artillery shells, land mines, depth charges, and torpedoes which are equipped with nuclear warheads. Also in this category are nuclear armed ground-based or shipborne surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and air-to-air missiles.

Small, two-man portable, or truck-portable, tactical weapons (sometimes misleadingly referred to as suitcase nukes), such as the Special Atomic Demolition Munition and the Davy Crockett recoilless rifle (recoilless smoothbore gun), have been developed, although the difficulty of combining sufficient yield with portability could limit their military utility. In wartime, such explosives could be used for demolishing "choke-points" to enemy offensives, such as at tunnels, narrow mountain passes, and long viaducts.

Other new tactical weapons undergoing research include earth penetrating weapons which are designed to target enemy-held caves or deep-underground bunkers.

There is no precise definition of the "tactical" category, neither considering range nor yield of the nuclear weapon.[2][3] The yield of tactical nuclear weapons is generally lower than that of strategic nuclear weapons, but larger ones are still very powerful, and some variable-yield warheads serve in both roles, for example the W89 200 kiloton (1/5Mt) warhead armed both the tactical Sea Lance anti-submarine rocket propelled depth charge and the strategic bomber launched SRAM II stand off missile. Modern tactical nuclear warheads have yields up to the tens of kilotons, or potentially hundreds, several times that of the weapons used in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Some tactical nuclear weapons have specific features meant to enhance their battlefield characteristics, such as variable yield which allow their explosive power to be varied over a wide range for different situations, or enhanced radiation weapons (the so-called "neutron bombs") which are meant to maximize ionizing radiation exposure while minimizing blast effects.

Strategic missiles and bombers are assigned preplanned targets including enemy airfields, radars, and surface to air defenses, not only counterforce strikes on hardened or wide area bomber, submarine, and missile bases. This strategic mission is to eliminate the enemy nation's national defenses to enable following bombers and missiles to more realistically threaten the enemy nation's strategic forces, command, and economy rather than targeting mobile military assets in near real time using tactical weapons optimized for time sensitive strike mission often in close proximity to friendly forces.[4]

Risk of escalating a conflict

Use of tactical nuclear weapons against similarly-armed opponents carries a significant danger of quickly escalating the conflict beyond anticipated boundaries, from the tactical to the strategic.[5][6][7][8][9][10] The existence and deployment of small, low-yield tactical nuclear warheads could be a dangerous encouragement to forward-basing and pre-emptive nuclear warfare,[11][12] as nuclear weapons with destructive yields of 10 tons of TNT (e.g., the W54 warhead design) might be used more willingly at times of crisis than warheads with yields of 100 kilotons.

For example, firing a low-yield nuclear artillery shell similar to the W48 (with a yield equivalent to 72 tons of TNT) at the enemy invites retaliation. It may provoke the enemy into responding with several nuclear artillery shells similar to the W79, which had a 1 kiloton yield. The response to these 1 kiloton nuclear artillery shells may be to retaliate by firing a tactical nuclear missile similar to a French Pluton (15 kiloton yield), Russian OTR-21 Tochka (100 kiloton yield) or the American MGM-52 Lance, fitted with a W70 variable yield warhead ranging between 1 and 100 kilotons. By using tactical nuclear weapons there is a high risk of escalating the conflict until it reaches a tipping point which provokes the use of strategic nuclear weapons such as ICBMs. Additionally, the tactical nuclear weapons most likely to be used first (i.e., the smallest, low-yield weapons such as nuclear artillery dating from the 1960s) have usually been under less stringent political control at times of military combat crises than strategic weapons.[13] Early Permissive Action Links could be as simple as a mechanical combination lock.[14] If a relatively junior officer in control of a small tactical nuclear weapon (e.g., the M29 Davy Crockett) were in imminent danger of being overwhelmed by enemy forces, he could request permission to fire it and due to decentralised control of warhead authorization, his request might quickly be granted during a crisis.

For these reasons, stockpiles of tactical nuclear warheads in most countries' arsenals have been dramatically reduced c. 2010, and the smallest types have been completely eliminated.[15] Additionally, the increased sophistication of "Category F" PAL mechanisms and their associated communications infrastructure mean that centralised control of tactical nuclear warheads (by the country's most senior political leaders) can now be retained, even during combat.

Some variable yield nuclear warheads such as the B61 nuclear bomb have been produced in both tactical and strategic versions. Whereas the lowest selectable yield of a tactical B61 (Mod 3 and Mod 4) is 0.3 kilotons (300 tons),[16] modern PAL mechanisms ensure that centralised political control is maintained over each weapon, including their destructive yields.

With the introduction of the B61 Mod 12, the United States will have four hundred identical nuclear bombs whose strategic or tactical nature will be set purely by the mission and target as well as type of aircraft on which they are carried.[17]

According to several reports including by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists quote Russian sources that as a result of the acceptability of USAF use of precision munitions with little collateral damage in the Kosovo conflict in what amounted to quick mass destruction of military assets once only possible with nuclear weapons or massive bombing against fellow Slavic Serbians. Vladimir Putin, then secretary of the Security Council of Russian Federation formulated a concept of using both tactical and strategic nuclear threats and strikes to de-escalate or cause an enemy to disengage from a conventional conflict threatening what Russia considered a strategic interest. This concept was formalized when Putin took power in Russia in the following year.[18][19][20]

Treaty control

Ten NATO member countries have advanced a confidence-building plan for NATO and Russia that could lead to treaties to reduce the tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.[21]

However in the meantime, NATO is moving forwards with a plan to upgrade its tactical nuclear weapons with precision guidance that would make them equivalent to strategic weapons in effects against hardened targets, and to carry them on stealth aircraft that are much more survivable against current air defenses.[22]

Examples

- Nasr

- W33 (nuclear weapon)

- B57 nuclear bomb

- W25 (nuclear warhead)

- Category:Nuclear mines

- Blue Peacock

- M-28 & M-29 Davy Crocketts with W54 nuclear warhead

- Red Beard

- Special Atomic Demolition Munition

- W85

See also

References

- ↑ Hans M Kristensen. "Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons (page 8)" (PDF). FAS. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ Brian Alexander, Alistair Millar, ed. (2003). Tactical nuclear weapons : emergent threats in an evolving security environment. (1. ed.). Washington DC: Brassey's. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-57488-585-9. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Some weapons could be tactical or strategic at the same time, depending only on the potential enemy. For example India nuclear missile with 500 km range is tactical when evaluated by Russian side, but understandably would be considered strategic if evaluated by Pakistan.

- ↑ "Strategic Air Command Declassifies Nuclear Target List from 1950s". nsarchive.gwu.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- ↑ http://web.mit.edu/SSP/Publications/confseries/russia/session10.htm

- ↑ Patchen, Martin (April 1988). Resolving disputes between nations: coercion or conciliation?. Duke University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-8223-0819-5. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ↑ "Getting to Zero Starts Here: Tactical Nuclear Weapons | Arms Control Association". www.armscontrol.org. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- ↑ Strachan, Hew (1988-01-01). European Armies and the Conduct of War. Routledge. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-415-07863-4. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ↑ Inc., Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, (May 1975). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc. p. 25. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ↑ http://www.pugwash.org/reports/nw/situgna.htm

- ↑ "Nuclear Threat Initiative | NTI". www.nti.org. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- ↑ http://cns.miis.edu/reports/tnw_nat.htm

- ↑ http://www.atomictraveler.com/RockIsland.pdf

- ↑ "Principles of Nuclear Weapons Security and Safety". nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- ↑ "Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces [INF] Chronology". fas.org. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- ↑ "The B61 Bomb". nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- ↑ Kristensen, Hans. "B61 LEP: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes." FAS, 15 June 2011.

- ↑ "Why Russia calls a limited nuclear strike "de-escalation"". 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- ↑ Colby, Elbridge. "The Role of Nuclear Weapons in the U.S.-Russian Relationship". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- ↑ Russia's Nonstrategic Nuclear Weapons, by Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Foreign Military Studies Office, Fort Leavenworth; published in Military Review May-June 2001

- ↑ Kristensen, Hans. "10 NATO Countries Want More Transparency for Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons." Federation of American Scientists, 24 April 2011.

- ↑ Kristensen, Hans M. "Germany and B61 Nuclear Bomb Modernization." FAS, 13 November 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tactical nuclear weapons. |