Tambov Rebellion

| Tambov Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russian Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Probably 20,000 regular and 20,000 militiamen [1] 14,000 (August 1920) [2] |

5,000 (November 1920) [3] 50,000 [6] - 100,000 [7] (March 1921) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

50,000 civilian internees in fields[4] 240,000 dead.[8] | |||||||

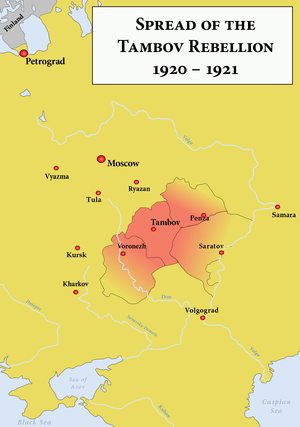

The Tambov Rebellion (Historically referred to in the Soviet Union as Antonovshchina), which occurred between 1920 and 1921, was one of the largest and best-organized peasant rebellions challenging the Bolshevik regime during the Russian Civil War.[9][10] The uprising took place in the territories of the modern Tambov Oblast and part of the Voronezh Oblast, less than 300 miles southeast of Moscow.

In Soviet historiography, the rebellion was referred to as the "Antonov's mutiny", or Antonovschina, named so after Alexander Antonov, a former official of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, a Chief of staff of the rebels. The movement was later portrayed by the Soviets as anarchical banditry, similar to other anti-Soviet movements that opposed them during this period.

Background

The rebellion was caused by the forced confiscation of grain by the Bolshevik authorities, a policy known in Russian as "prodrazvyorstka". In 1920, the requisitions were increased from 18 million to 27 million poods in the region. This caused the peasants to reduce their grain production since they knew that anything they did not consume themselves would be immediately confiscated. Filling the state quotas meant death for many by starvation.[10]

The revolt began on 19 August 1920 in a small town of Khitrovo, where a military requisitioning detachment of the Red Army appropriated everything they could and "beat up elderly men of seventy in full view of the public".[10]

A distinctive feature of this rebellion, among the many of these times, was that it was led by a political organization, the Union of Working Peasants (Soyuz Trudovogo Krestyanstva). A Congress of Tambov rebels abolished Soviet power and created the Constituent Assembly that called for universal suffrage and land reform. A major tenet proposed by them was returning all land to the peasants.[9]

On 2 February 1921, the Soviet leadership announced the end of the "prodrazvyorstka", and issued a special decree directed at peasants from the region implementing the "prodnalog" policy. The new policy was essentially a tax on grain and other foodstuffs. This was done prior to the 10th Congress of the Bolsheviks, when the measure was officially adopted. The announcement began circulating in the Tambov area on 9 February 1921. The Tambov uprising and unrest elsewhere were significant reasons that the "prodnalog" policy was implemented and the "prodrazvyorstka" was abandoned.

Timeline

Alexander Antonov, a radical member of the Left Socialist Revolutionaries, had sided with the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution in 1917, but he became disenchanted with them after they implemented a policy of grain requisition in 1918. Antonov became a popular hero to the people of the Tambov region of central Russia where he started his campaigns.

In October 1920 the peasant army numbered over 50,000 fighters; numerous deserters from the Red Army joined it. The rebel militia proved highly effective and even infiltrated the Tambov Cheka.[10] Alexander Schlichter, Chairman of the Tambov Gubernia Executive Committee, contacted Vladimir Lenin, who ordered Red Army reinforcements to the area.[11] In January 1921 peasant revolts spread to Samara, Saratov, Tsaritsyn, Astrakhan and Siberia. In February, the peasant army reached its peak, numbering up to 70,000 and successfully defending the area against Bolshevik expeditions.

The seriousness of the uprising caused the establishment of the "Plenipotentiary Commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Bolshevik Party for the Liquidation of Banditry in the Gubernia of Tambov". With the end of the Polish–Soviet War (in March 1921) and the defeat of General Wrangel in 1920, the Red Army could divert its regular troops into the area - deploying in total over 100,000 Red Army soldiers, alongside special Cheka detachments.[10]

The Red Army, under the command of Mikhail Tukhachevsky, used heavy artillery and armoured trains and also engaged in the summary execution of civilians. Tukhachevsky and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko signed an order, dated 12 June 1921, which stipulated:

"The forests where the bandits are hiding are to be cleared by the use of poison gas. This must be carefully calculated, so that the layer of gas penetrates the forests and kills everyone hiding there."[10]

The Bolshevik forces used chemical weapons "from end of June 1921 until apparently the fall of 1921", by direct order from the leadership of Red Army and from the Communist Party.[12] Publications in local Communist newspapers openly glorified liquidations of "bandits" with the poison gas.[12]

Seven concentration camps were set up. At least 50,000 people were interned, mostly women, children, and the elderly - some of them sent to the camps as hostages. Each month 15 to 20 percent of inmates in the camps died.[10]

The Bolsheviks gradually quelled the uprising in the course of 1921. Antonov was killed in 1922 during an attempt to arrest him. Sennikov estimated the total losses among the population of Tambov region in 1920 to 1922 resulting from the war, executions, and imprisonment in concentration camps as approximately 240,000.[13]

Recovery of documents

Some documents relating to the rebellion were found by the local ethnographer Boris Sennikov in 1982 while he was engaged in clearing sand from the altar of the Winter Church of the Kazan monastery [14] During the 1920s, the monastery had been requisitioned for use as the local Cheka headquarters and the church had served as the archive of the Tambov Military Commissariat.

In 1933, the local government decided to burn documents that could compromise the Soviet regime. However, during the process, the fire grew out of control and had to be extinguished by water and, crucially, sand. All documents in the archive were believed to be destroyed; as the church altar was not used by the archive, the surviving documents, covered by a layer of sand, had never been found. In 1982, the local archive changed its address and the church became abandoned. When Sennikov found the documents, the Tambov department of KGB opened a criminal case against him. Later, the case was closed, but Sennikov lost his job.

In 2004, the publishing house Posev published the Sennikov archive as part of The Tambov Rebellion and the Liquidation of Russian Peasantry[12] along with documents relating to the Governorate Military Commissariat (including those dealing with Konstantin Mamontov's 1919 anti-Bolshevik raid, and those describing the Great Purge of the 1930s). The documents also included Red Army orders issued during the rebellion, correspondence, reports of the use of chemical weapons against the peasant rebels, and documents of the Union of the Working Peasants.

In popular culture

- Some scenes of the rebellion are depicted in movie Once Upon a Time There Lived a Simple Woman by Andrei Smirnov.

- Apricot Jam and Other Stories (2010) by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. In a short story about Marshal Georgy Zhukov's futile attempts at writing his memoirs, the retired Marshal reminisces about being a young officer fighting against the Union of Working Peasants. He recalls Mikhail Tukhachevsky's arrival to take command of the campaign and his first address to his men. He announced that total war and scorched earth tactics are to be used against civilians who assist or even sympathize with the Union. Zhukov proudly recalls how Tukhachevsky's tactics were adopted and succeeded in breaking the uprising. In the process, however, they virtually depopulated the surrounding countryside.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Hosking, 1993: 78; Mayer, 2000: 392

- ↑ Powell, 2007: 219; Werth, 1998: 131

- 1 2 Powell, 2007: 219; Werth, 1998: 132

- 1 2 3 Werth, 1998: 139

- ↑ Waller, 2012: 194

- ↑ Figes, 1998: 811; Mayer, 2000: 392

- ↑ Waller, 2012: 115; Werth, 1998: 132, 138

- ↑ Sennikov, B.V. (2004). Tambov rebellion and liquidation of peasants in Russia. Moscow: Posev. In Russian. ISBN 5-85824-152-2

- 1 2 Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine Oxford University Press New York (1986) ISBN 0-19-504054-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stéphane Courtois, The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Harvard University Press, 1999, hardcover, 858 pages, ISBN 0-674-07608-7.

- ↑ Lenin to Kornev 19 October, 1920. Accessed 21 December 2008.

- 1 2 3 Publisher: Posev, 2004, ISBN 5-85824-152-2 B.V.Sennikov. Tambov rebellion and liquidation of peasants in Russia Full text in Russian

- ↑ Sennikov, Boris V. (2004). Тамбовское восстание 1918-1921 гг. и раскрестьянивание России 1929-1933гг.: "Тамбовская Вандея" [The Tambov uprising of 1918 to 1921 and the de-peasantisation of Russia of 1929 to 1933: "The Tambov Vendee"]. Серия "Библиотечка россиеведения" (in Russian). Moscow: Посев. ISBN 5-85824-152-2. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

Во всяком случае, по самым осторожным подсчетам, потери населения Тамбовской губернии в 1920-1922 гг. составили около 240 тыс. человек. [In any case, according to the most careful reckoning, the losses of the residents of the Tambov Governorate in the years 1920 to 1922 amounted to approximately 240 thousand persons.]

- ↑ An illustrated article about Tambov revolt from Gulag website (Russian).

Further reading

- Seth Singleton, "The Tambov Revolt (1920-1921)," Slavic Review, vol. 25, no. 3 (Sept. 1966), pp. 497–512. In JSTOR

External links

- Tukhachvsky role in the Tambov revolt, including the text of commands given to the red army concerning the use of war gases, taking and executing hostages, deporting of peasant families to Concentration camps. (In Russian)

- Programme of Union of Toiling Peasants

- (in Russian) Antonovshchina: a wealth of historical documents, including the documents from the rebel side

- Great site with lots of bibliography for further research (English)

Coordinates: 52°43′N 41°25′E / 52.717°N 41.417°E