Tyrolean Rebellion

| Tyrolean Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Fifth Coalition | |||||||

Homecoming of Tyrolean Militia in the War of 1809 by Franz Defregger | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 42,000 | 20,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,000 | 2,500 | ||||||

The Tyrolean Rebellion of 1809 (German: Tiroler Volksaufstand) was a rebellion of peasants in the County of Tyrol led by Andreas Hofer against the occupation of their homeland by the French and Bavarian troops within the context of the War of the Fifth Coalition against Napoleon I.

Historical background: Bavarian occupation of Tyrol since 1805

In September 1805 the Electorate of Bavaria under Prince-elector Maximilian I Joseph of Wittelsbach, that had been allied with the Habsburg Monarchy under the common federally structured Holy Roman Empire, went over to Napoleonic France: the Bavarian Minister Count Maximilian von Montgelas, realizing the French superiority while fearing the ambitions of the newly established Austrian Empire, signed a secret defence alliance at Bogenhausen. At the end of the War of the Third Coalition shortly afterwards, Bavaria found itself on the victorious side. Upon the 1805 Peace of Pressburg it not only was elevated to a kingdom, it also gained French-occupied Tyrol, which since 1363 had been held by the Austrian Habsburgs, who, heavily defeated by Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz, were forced to renounce it. The French officially handed over the Tyrolean county including the secularized Bishopric of Trent (Trentino) to Bavaria on 11 February 1806.

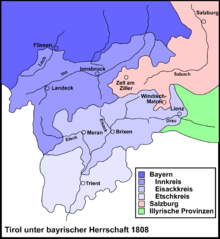

In its policies, the Bavarian government under Count Montgelas angered the Tyrolean population by raising taxes there, but at the same time barring exports, e.g. of cattle, from Tyrol into Bavaria. Furthermore, the state mingled into the affairs of the church in Tyrol, banning traditional rural holidays, the ringing of church bells, processions etc. which were a vital part of Tyrolean culture. Additionally, on May 1, 1808, the County of Tyrol was disestablished and administratively split up into the three districts of Inn, Eisack and Etsch. The new Bavarian constitution also replaced the old Tyrolean constitution that had given privileges to the population, such as not having to fight in a foreign army and outside of the Tyrolean borders. Conscription was thus introduced in Tyrol and Tyroleans called into Bavarian military service, which led to open revolt.

The war of the Fifth Coalition and outbreak and course of the rebellion

The trigger for the outbreak of the uprising was the flight to Innsbruck of young men that were due to be called into the Bavarian army by the authorities at Axams on March 12 and 13, 1809. The partisans stayed in contact with the Austrian court in Vienna by their conduit Baron Joseph Hormayr, an Innsbruck-born Hofrat and close friend of Archduke John of Austria. The Austrian Empire, citing a breach of the conditions agreed in the Peace of Pressburg guaranteeing Tyrolean constitutional autonomy, declared war on the Bavarian-French allies on April 9, 1809. Archduke John explicitly stated that Bavaria had forfeit all rights to Tyrol, which rightfully belonged with the Austrian lands, and therefore any resistance against Bavarian occupation would be legitimate.

An Austrian corps under General Johann Gabriel Chasteler de Courcelles operating from Carinthia occupied Lienz and marched against Innsbruck, but was defeated by Bavarian troops led by French Marshal François Joseph Lefebvre near Wörgl on May 13. Meanwhile, an irregular army led by the innkeeper Andreas Hofer upon the war message had gathered around Sterzing and marched north towards the Brenner Pass. In the First and Second Battle of Bergisel near Innsbruck on April 12 and May 25, the peasant troops clashed with the Bavarians, who were forced to retreat.

The Tyroleans celebrated the news that Napoleon had suffered his first defeat at the Battle of Aspern-Essling on May 22. Nevertheless, after the French again gained the upper hand at the Battle of Wagram on July 5/6, Archduke Charles of Austria signed the Armistice of Znaim whereafter the Austrian forces withdraw from Tyrol. Thus, the rebels, who had their strongholds in Southern Tyrol, were left fighting alone. They however were able to inflict several defeats to the French and Bavarians forces under Marshal Lefebvre in July, culminating in a complete French retreat after the Third Battle of Bergisel on August 12/13. Hofer now took over the administration of the unoccupied territories at Innsbruck; large parts of Tyrol enjoyed a brief period of independence.

However, in the Treaty of Schönbrunn of October 14, the peace treaty ending the War of the Fifth Coalition, Emperor Francis I of Austria officially gave up any claims to Tyrol. Napoleon ordered the re-conquest of the province the same day. A combination of French military force under the new command of General Jean-Baptiste Drouet and diplomatic de-escalation measures by the rather pro-Tyrolean and anti-Napoleonic Bavarian commander, Prince Ludwig I, was successful in decreasing the numbers of rebel troops that were ready to fight to the death. Those last loyal troops were defeated at the Fourth Battle of Bergisel on November 1, that effectively crushed the rebellion despite minor rebel victories later in November.

Aftermath and execution of Andreas Hofer

Many of the rebels were executed by the French and Bavarian forces in the following weeks. The leader Andreas Hofer fled into the mountains and hid at several places in South Tyrol. He was betrayed by a Tyrolean peasant to the French near St Martin in Passeier on 28 January 1810. Hofer was arrested and brought to Mantua, where Eugène de Beauharnais, the French viceroy of Italy, first wanted to pardon him, but was overruled by his stepfather Napoleon. The death penalty was issued on February 19 and executed the next day. Hofer's mortal remains were buried at the Innsbruck Hofkirche in 1823.

In consequence of the insurrection, Bavaria pressurised by the French on 28 February 1810 had to cede large parts of Southern Tyrol with the Trentino to Italy and the eastern Hochpustertal with Lienz to the Illyrian Provinces. Upon Napoleon's fall in 1814 and the Congress of Vienna, all parts of Tyrol were re-united under Austrian rule.

With the rise of nationalism in the 19th century, the tragic fate of the rebellion and of Andreas Hofer became a national myth especially for the German speaking Tyroleans. The song Zu Mantua in Banden deals with the death of Hofer and his vain resistance against the "foreign" occupants. It became the anthem of the Austrian State of Tyrol in 1948. Hofer's life and death was the model for the 1923 film Der Rebell by Luis Trenker.

Further reading

- Eyck, F. Gunther (1986). Loyal Rebels: Andreas Hofer and the Tyrolean Uprising of 1809. University Press of America.