Tax increment financing

Tax increment financing (TIF) is a public financing method that is used as a subsidy for redevelopment, infrastructure, and other community-improvement projects in many countries, including the United States. Similar or related value capture strategies are used around the world. Through the use of TIF, municipalities typically divert future property tax revenue increases from a defined area or district toward an economic development project or public improvement project in the community."The first TIF was used in California in 1952.[1] By 2004, all 50 American States had authorized the use of TIF.[1]:7[2] The first TIF in Canada was used in 2007.[3] As the use of TIFs increases elsewhere, in California, where they were first conceived, in 2011 Governor Jerry Brown enacted legislation which led to elimination of California’s nearly 400 redevelopment agencies that implemented TIFs, in response to California's Fiscal 2010 Emergency Proclamation thereby stopping the diversion of property tax revenues from public funding. The RDAs are appealing this decision.[4] TIF subsidies are not appropriated directly from a city's budget, but the city incurs loss through foregone tax revenue.[5]

Use and common downsides

Tax increment financing (TIF) subsidies, which are used for both publicly subsidized economic development and municipal projects,[5]:2 have provided the means for cities and counties to gain approval of redevelopment of blighted properties or public projects such as city halls, parks, libraries etc. The definition of blight has taken on a broad inclusion of nearly every type of land including farmland, which has given rise to much of the criticism. "[5]:2

To provide the needed subsidy, the urban renewal district, or TIF district, is essentially always drawn around hundreds or thousands of acres of additional real estate (beyond the project site) to provide the needed borrowing capacity for the project or projects. The borrowing capacity is established by committing all normal yearly future real estate tax increases from every parcel in the TIF district (for 20–25 years, or more) along with the anticipated new tax revenue eventually coming from the project or projects themselves. If the projects are public improvements paying no real estate taxes, all of the repayment will come from the adjacent properties within the TIF district.

Although questioned, it is often presumed that even public improvements trigger gains in taxes above what occurs, or would have occurred in the district without the investment. In many jurisdictions yearly property tax increases are restricted and cannot exceed what would otherwise have occurred.

The completion of a public or private project can at times result in an increase in the value of surrounding real estate, which generates additional tax revenue. Sales-tax revenue may also increase, and jobs may be added, although these factors and their multipliers usually do not influence the structure of TIF.

The routine yearly increases district-wide, along with any increase in site value from the public and private investment, generate an increase in tax revenues. This is the "tax increment." Tax increment financing dedicates tax increments within a certain defined district to finance the debt that is issued to pay for the project. TIF was designed to channel funding toward improvements in distressed, underdeveloped, or underutilized parts of a jurisdiction where development might otherwise not occur. TIF creates funding for public or private projects by borrowing against the future increase in these property-tax revenues.[6]

History

Although the TIF method has been discontinued in the state it began in, California, thousands of TIF districts still currently operate nationwide in the US, from small and mid-sized cities, to the State of California which will be paying off debt on old TIFs for years to come. As of 2008, California had over four hundred TIF districts with an aggregate of over $10 billion per year in revenues, over $28 billion of long-term debt, and over $674 billion of assessed land valuation.[7] TIF began in California in 1952, but the state has currently discontinued the use of them due to lawsuits.[8][9]

With the exception of Arizona, every state and the District of Columbia has enabled legislation for tax increment financing.[10] Some states, such as Illinois, have used TIF for decades, but others have only recently embraced TIF.[11] The state of Maine has a program named TIF; however, this title refers to a process very different than in most states.[12]

Since the 1970s, the following factors have led local governments (cities, townships, etc.) to consider tax increment financing: lobbying by developers, a reduction in federal funding for redevelopment-related activities (including spending increases), restrictions on municipal bonds (which are tax-exempt bonds), the transfer of urban policy to local governments, State-imposed caps on municipal property tax collections, and State-imposed limits on the amounts and types of city expenditures. Considering these factors, many local governments have chosen TIF as a way to strengthen their tax bases, attract private investment, and increase economic activity.

Urban regeneration best practices

In a 2015 literature review on best practices in urban regeneration, with cities across the United States seeking ways to reverse trends of unemployment, declining population and disinvestment in their core downtown areas, as developers continue to expand into suburban areas. Re-investment in downtown core areas include mixed-use development and new or improved transit systems. With successful revitalization comes gentrification with higher property values and taxes, and the exodus of lower income earners.[13][14]

"Successful city revitalization can’t be achieved by megaprojects alone — signature buildings, stadiums or other such concentrated development efforts. Instead, "it must be multifaceted and encompass improvements to the cities’ physical environments, their economic bases, and the social and economic conditions of their residents."— Mallach and Date 2013

Unintended consequences of TIF subsidies

TIF districts have attracted much criticism. Some question whether TIF districts actually serve their resident populations. An organization called Municipal Officials for Redevelopment Reform (MORR) holds regular conferences on redevelopment abuse.[15]

Here are further claims made by TIF opponents:

- as investment in an area increases, it is not uncommon for real estate values to rise and for gentrification to occur.

- Although generally sold to legislatures as a tool to redevelop blighted areas, some districts are drawn up where development would happen anyway, such as ideal development areas at the edges of cities. California has passed legislation designed to curb this abuse.[16][17]

- The designation of urban areas as "blighted,"[18] essential to most TIF implementation, can allow governmental condemnation of property through eminent domain laws. The famous Kelo v. City of New London United States Supreme Court case, where homes were condemned for a private development, arose over actions within a TIF district.

- The TIF process arguably leads to favoritism for politically connected developers, implementing attorneys, economic development officials, and others involved in the processes.

- In some cases, school districts within communities using TIF are experiencing larger increases in state aid than districts not in such communities. This may be creating an incentive for governments to "over-TIF," consequently taking on riskier development projects. Local governments are under no obligation to recognize when TIF designation would adversely affect a school district's financial condition, and consequently the quality of some schools can be compromised.

- Normal inflationary increases in property values can be captured with districts in poorly written TIFs, representing money that would have gone into the public coffers even without the financed improvements.

- Districts can be drawn excessively large thus capturing revenue from areas that would have appreciated in value regardless of TIF designation.

- Approval of districts can sometimes capture one entity's future taxes without its official input, i.e. a school districts taxes will be frozen on action of a city.

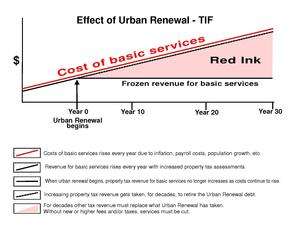

- Capturing the full tax increment and directing it to repay the development bonds ignores the fact that the incremental increase in property value likely requires an increase in the provision of public services, which will now have to be funded from elsewhere (often from subsidies from less economically thriving areas). For example, the use of tax increment financing to create a large residential development means that public services from schools to public safety will need to be expanded, yet if the full tax increment is captured to repay the development bonds, other money will have to be used.[19][20]

Examples

Chicago

The city of Chicago, in Cook County, Illinois, has a significant number of TIF districts and has become a prime location for examining the benefits and disadvantages of TIF districts. The city runs 131 districts with tax receipts totaling upwards of $500 million for 2006.[21] Lori Healey, appointed commissioner of the city's Planning and Development department in 2005 was instrumental in the process of approving TIF districts as first deputy commissioner.

The Chicago Reader, a Chicago alternative newspaper published weekly, has published articles regarding tax increment financing districts in and around Chicago. Written by staff writer Ben Joravsky, the articles are critical of tax increment financing districts as implemented in Chicago.[22]

Cook County Clerk David Orr, in order to bring transparency to Chicago and Cook County tax increment financing districts, began to feature information regarding Chicago area districts on his office's website.[23] The information featured includes City of Chicago TIF revenue by year, maps of Chicago and Cook County suburban municipalities' TIF districts.

The Neighborhood Capital Budget Group of Chicago, Illinois, a non-profit organization, advocated for area resident participation in capital programs. The group also researched and analyzed the expansion of Chicago's TIF districts.[24]

In April 2009, the "TIF Sunshine Ordinance" introduced by Alderman Scott Waguespack and Alderman Manuel Flores (then 1st Ward Alderman) passed City Council. The ordinance made all TIF Redevelopment Agreements and attachments available on the City’s website in a searchable electronic format. The proposal intended to improve the overall transparency of TIF Agreements, thereby facilitating significantly increased public accountability.[25]

According to an article published in the Journal of Property Tax Assessment & Administration in 2009, the increase in the use of TIF in Chicago resulted in a "substantial portion of Chicago's property tax base and the land area" being subsumed by these levy zones — "26 percent of the city’s land area and almost a quarter of the total value of commercial property is in TIF districts" by 2007. The study notes the difficulties in establishing how effective TIF are.[1]

Albuquerque

Currently, the 2nd largest TIF project in America is located in Albuquerque, New Mexico: the $500 million Mesa del Sol development. Mesa del Sol is controversial in that the proposed development would be built upon a "green field" that presently generates little tax revenue and any increase in tax revenue would be diverted into a tax increment financing fund. This "increment" thus would leave governmental bodies without funding from the developed area that is necessary for the governmental bodies' operation.

Detroit

In July 2014, Detroit's Downtown Development Authority announced TIF financing for the new Red Wings hockey stadium. The total project cost, including additional private investments in retail and housing, is estimated at $650 million, of which $250 million will be financed using TIF capture to repay 30-year tax exempt bonds purchased by the Michigan Strategic Fund, the state's economic development arm.

California

In an article published in 1998 the Public Policy Institute of California, Michael Dardia challenged the governing redevelopment agencies' (RDAs) assumption "that redevelopment pays for itself through tax increment financing. The claim is that RDAs "receive any increase in property tax revenues (above a 2 percent inflation factor) in project areas because their investment in area improvements is responsible for increasing property values."[26]:ii Dardia argued that property tax revenues channeled to tax increment financing results in revenues lost to "other local jurisdictions—the county, schools, and special districts"[26] and if the RDAs "are not largely responsible for the increase in property values, those jurisdictions are, in effect, subsidizing redevelopment, with no say in how the revenues are used."[26]

"In fiscal year 1994–1995—the most recent year for which figures are available—redevelopment agencies (RDAs) received 8 percent of the property tax revenues collected in the state of California, amounting to $1.5 billion. These are revenues that, absent the RDAs, would have gone to other public agencies such as the state and counties."— Michael Dardia 1998

By December 6, 2010 Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger issued a fiscal emergency[27] which was reaffirmed by Governor Jerry Brown in December 2011 to underscore "the need for immediate legislative action to address California’s massive budget deficit." Governor Brown enacted measures to stabilize school funding by reducing or eliminating the diversion of property taxes from the public sector including, school districts, to RDAs. New legislation including Assembly Bill 26 and Assembly Bill 27 were passed, which led to the elimination of California’s nearly 400 redevelopment agencies thereby stopping the diversion of property tax revenues from public funding. The RDAs are appealing this decision.[4]

Alameda, California

In 2009, SunCal Companies, an Irvine, California-based developer, introduced a ballot initiative that embodied a redevelopment plan for the former Naval Air Station Alameda and a financial plan based in part on roughly $200 million worth of tax increment financing to pay for public amenities. SunCal structured the initiative so that the provision of public amenities was contingent on receiving tax increment financing, and on the creation of a community facilities (Mello-Roos) district, which would levy a special (extra) tax on property owners within the development.[28] Since Alameda City Council did not extend the Exclusive Negotiation Agreement with Suncal, this project will not move forward. In California, Community Redevelopment Law governs the use of tax increment financing by public agencies.[29]

Iowa

In 2002 economists at Department of Economics Iowa State University, claimed that "existing taxpayers, its householders, wage earners, and retirees are aggressively subsidizing business growth and population" TIF designated zones in Iowa.[30]

Wisconsin

TIFs were established in Wisconsin in 1975. In 2001 critics argued that TIF supported developers to develop in green spaces citing a 2000 1,000 Friends of Wisconsin report which stated that 45% of tax incremental financing districts were used to develop open space land.[31][32]

Denver

From 1995 through 2005 Denver tax payers were able to leverage over $5 billion in private investment by committing to over half a billion dollars of TIF subsidies. At that time new TIF subsidized projects under consideration included the "redevelopment of the old Gates Rubber Factory complex at I-25 and Broadway, and the realization of Denver’s ambitious plans for the downtown Union Station area."[5]:6 Denver's urban landscape was transformed from 1995 through 2005 through TIF-subsidized projects such as "the landmark resurrection" of the Denver Dry Goods building, the Adams Mark hotel, Denver Pavilions, and REI flagship store, Broadway Marketplace shopping area and the demolition of the old Woolworth’s building, the relocation and expansion of Elitch’s into the Six Flags Elitch Gardens Amusement park, the redevelopment of Lowry Air Force Base and the redevelopment of the old Stapleton airport – "the largest urban infill project in the nation."[5]:6

By 2005 the City Denver had already "mortgaged over $500 million in future tax revenue to pay off existing TIF subsidies to private developers" and was preparing to "increase that sum substantially with several new TIF projects in the next five years." In 2005 the "diversions of tax revenue to pay for TIF subsidies [represented] an annual cost of almost $30 million to Denver taxpayers, and [were] rising rapidly."[5]:2 By 2007 TIF tax expenditures in the form of foregone tax revenue totaled nearly "$30 million annually – equal to almost 7% of Denver’s entire annual General Fund revenues" and at that time the amount was rapidly increasing.[5]:6 In a 2005 study it was revealed through wage surveys at TIF projects "that jobs there pay substantially less than Denver average wages, and 14%-27% less even than average wages for comparable occupational categories."[5]:2

In part 1 of a three part series researchers "explained the history and mechanics of TIF, and analyzed the total cost of TIF to Denver taxpayers, including “hidden” costs from increased public service burdens that TIF projects do not pay for."[33] In "Who Profits from TIF Subsidies?" researchers "examined the types of businesses Denver attracts through TIF, and the profit rates of developers with whom Denver partners to bring TIF projects into existence, and the transparency of the TIF approval process."[34] In part three of the study researchers examined "quality and housing affordability at TIF-subsidized projects."[5]:2

Applications and administration

Cities use TIF to finance public infrastructure, land acquisition, demolition, utilities and planning costs, and other improvements including sewer expansion and repair, curb and sidewalk work, storm drainage, traffic control, street construction and expansion, street lighting, water supply, landscaping, park improvements, environmental remediation, bridge construction and repair, and parking structures.

State enabling legislation gives local governments the authority to designate tax increment financing districts. The district usually lasts 20 years, or enough time to pay back the bonds issued to fund the improvements. While arrangements vary, it is common to have a city government assuming the administrative role, making decisions about how and where the tool is applied.[35]

Most jurisdictions only allow bonds to be floated based upon a portion (usually capped at 50%) of the assumed increase in tax revenues. For example, if a $5,000,000 annual tax increment is expected in a development, which would cover the financing costs of a $50,000,000 bond, only a $25,000,000 bond would be typically allowed. If the project is moderately successful, this would mean that a good portion of the expected annual tax revenues (in this case over $2,000,000) would be dedicated to other public purposes other than paying off the bond.

Community revitalization levy (CRL) in Canada

By 2015 major Canadian cities had already implemented community revitalization levies (CRL) — the term used for TIFs in Canada.[3]

Alberta

In April 2012, it was proposed that the Alberta government change regulations so that the Community Revitalization Levy (CRL) could be applied to remediation costs "incurred by a private developer."[36]:18

"The CRL does not currently allow the levy to be used for remediation costs incurred by a private developer. While the CRL is quite a comprehensive approach that is not widely used, it is suggested that a change in regulation to allow the levy to apply to remediation costs would provide incentive to brownfield redevelopment in applicable circumstances."— 13 April 2012 Alberta Brownfield Redevelopment Working Group

The Calgary Municipal Land Corporation (CMLC) — an arms-length a subsidiary of the City of Calgary, established in 2007, to revisit land use in the longtime deserted chunk of land in the east downtown core along the Bow River[37] — used a CRL to develop Downtown East Village, Calgary making Calgary the first Canadian city to use the CRL.[3] The CMLC "committed approximately $CDN 357 million to East Village infrastructure and development" and claims that it "has attracted $CDN 2.4 billion of planned development that is expected to return $CDN 725 million of revenue to the CRL."[3] The designated levy zone for the Rivers District CRL is wider than the East Village, making it financially sound since it collects taxes for twenty years on its anchor building, the 58-storey Bow tower, and from developments in nearby Victoria Park (Calgary).[18]

In an interview with the Calgary Sun in February 2015, Michael Brown, CRL president and CEO said they were looking into a CRL[18] for the development of the West Village similar to that used to finance the remediation of the East Village. In August CalgaryNEXT sports complex was proposed as a potential anchor to the levy zone. Local politicians expressed concern about the funding model, which proposed that the city would front between $440 and $690 million of the projected cost, most which would only be recouped over a long period of time.[38] Mayor Naheed Nenshi commented that one of a number of challenges to the CalgaryNEXT proposal was the requirement of a community revitalization levy, along with the need for a land contribution from the City, "and significant investments in infrastructure to make the West Village a complete and vibrant community."[39] Edmonton, Alberta creating a CRL to revitalize the downtown with a massive development project including a new arena, park development and upgrades including sewers which total approximately $CDN 500 million.[3] The city hopes to "generate approximately $941 million in revenue in a medium-growth scenario."[3]

Ontario

Toronto's Mayor John Tory plans on creating a levy zone to finance a massive $CDN 2.7-billion SmartTrack surface rail line project spanning 53 kilometres.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Sherri Farris; John Horbas (2008). "Creation vs. Capture: Evaluating the True Costs of Tax Increment Financing" (PDF). Journal of Property Tax Assessment & Administration. 6 (4). Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Kevin Ward. "Tax Increment Financing: Imagining Urban Futures: Research on the circulation of the Tax Increment Financing model across North America and the UK". Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kyle Bakx (May 22, 2015). "Risky business as Canadian cities turn to neighbourhood levies: Expert warns the levies can be 'direct subsidies for the developers'". CBC News. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- 1 2 "City of Ceritos et al. v. State of California". California Courts - State of California. 25 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Tony Robinson; Chris Nevitt; Robin Kniech (2005). "Are We Getting Our Money's Worth? Tax-Increment Financing and new ideas new priorities new economy Urban Redevelopment In Denver Part III: Are We Building a Better Denver ?: Job Quality & Housing Affordability at TIF-Subsidized Projects" (PDF). Front Range Economic Strategy Center. p. 57. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ Various, (2001). Tax Increment Financing and Economic Development, Uses, Structures and Impact. Edited by Craig L. Johnson and Joyce Y. Man. State University of New York Press.

- ↑ California State Controller's Annual Report on Redevelopment Agencies, 2007-2008 (PDF)

- ↑ "Urban Renewal Dead in California," The Antiplanner, Thoreau Institute (2 January 2012).

- ↑ See California Redevelopment Association v. Ana Matosantos.

- ↑ Council of Development Finance Agencies 2008 TIF State-By-State Report accessed 2014-3-21.

- ↑ Arkansas (2000), Washington (2001), New Jersey (2002), Delaware (2003), Louisiana (2003), North Carolina (2005), and New Mexico (2006).

- ↑ Michael Havlin (25 May 2013). "Maine Voices: TIF helps communities that don't need it: State economic development support should go to towns that can't now take advantage of complex property tax schemes". Hampton, Maine: Portland Press Herald. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Urban regeneration: What recent research says about best practices". Harvard Kennedy School's Shorenstein Center and the Carnegie-Knight Initiative. Journalists Resource. January 29, 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Alan Mallach; Lavea Date (May 2013). "Regenerating America's Legacy Cities". Brachman Publication. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-55844-279-5. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Redevelopment.com website". Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ "Redevelopment: The unknown government". Coalition for Redevelopment Reform. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ "Subsidizing Redevelopment in California" (PDF). Public Policy Institute of California. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- 1 2 3 James Wilt (10 January 2013). "Blighted streets, no more". Fast Forward Weekly. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Richard Dye; David Merriman (September 1999). James H. Kuklinski, ed. "The Effects of Tax-Increment Financing on Economic Development" (PDF). American Dream Coalition. p. 47. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Richard Dye; David Merriman (2000). "The Effects of Tax-Increment Financing on Economic Development". Journal of Urban Economics. 47 (2): 306–328.

- ↑ "City of Chicago TIF Revenue Totals by Year 1986-2013" (PDF). Cook County Clerk's Office. Retrieved 2014-08-19.

- ↑ "articles by Reader staff writer Ben Joravsky on Chicago's TIF (tax increment financing) districts". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ "TIFs 101: A taxpayer's primer for understanding TIFs". Cook County Clerk's Office. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ "Research". Neighborhood Capital Budget Group of Chicago, Illinois. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ "Research". 32ND WARD SERVICE OFFICE. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- 1 2 3 Michael Dardia (January 1998), "Subsidizing Redevelopment in California" (PDF), Public Policy Institute of California, retrieved 28 August 2015

- ↑ "Fiscal Emergency Proclamation by the Governor of the State of California". Governor of the State of California. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Alameda Point Development Initiative Election Report Executive Summary Part I" (PDF). City of Alameda. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ "California Community Redevelopment Law". Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ David Swenson & Liesl Eathington (2002). "* David Swenson and Liesl Eathington, "Do Tax Increment Finance Districts in Iowa Spur Regional Economic and Demographic Growth?" (2002)." (PDF). Department of Economics Iowa State University. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ David E. Wood, Mary Beth Hughes (April 2001), "From Stumps to Dumps: Wisconsin's Anti-Environmental Subsidies" (PDF), Center on Wisconsin Strategy, University of Wisconsin–Madison, retrieved 28 August 2015

- ↑ Matthew Mayrl (2005). Refocusing Wisconsin’s TIF System On Urban Redevelopment: Three Reforms (PDF). Center on Wisconsin Strategy, University of Wisconsin–Madison) titled (Report).

- ↑ Tony Robinson; Chris Nevitt; Robin Kniech (2005). "Are We Getting Our Money's Worth? Tax-Increment Financing and new ideas new priorities new economy Urban Redevelopment In Denver Part I: What Do TIF Subsidies Cost Denver?". Front Range Economic Strategy Center.

- ↑ Tony Robinson; Chris Nevitt; Robin Kniech (2005). "Are We Getting Our Money's Worth? Tax-Increment Financing and new ideas new priorities new economy Urban Redevelopment In Denver Part II: Who Profits from TIF Subsidies?". Front Range Economic Strategy Center.

- ↑ "Growth Within Bounds: Report of the Commission on Local Governance for the 21st Century" (PDF). State of California. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ Alberta Brownfield Redevelopment Working Group (13 April 2012). "Alberta Brownfield Redevelopment: practical approaches to achieve productive community used" (PDF). Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development (ESRD). Alberta Brownfield Redevelopment Working Group. p. 48. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ↑ Barb Livingstone (14 August 2015). "Calgary's urban influencer series: Michael Brown". CREB. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Johnson, George (2015-08-19). "Let King begin the courtship". Calgary Herald. p. C1.

- ↑ "Statement from Mayor Naheed Nenshi regarding the "CalgaryNext"". Office of the Mayor, City of Calgary. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

External links

- Scott, Brendan S., 2013 "Factors that Influence the Size of Tax Increment Financing Districts in Texas" Applied Research Project, Texas State University.

- An abstract of Weber's Equity and Entrepreneurialism: The Impact of Tax Increment Financing on School Finance (2003).

- An abstract of Weber, et al.'s "Does Tax Increment Financing Raise Urban Industrial Property Values?" (2003).

- Kenneth Hubbell, Peter J. (June 1997), "Tax Increment Financing in the State of Missouri MSCDC Economic Report" (PDF), Eaton Center for Economic Information, University of Missouri-Kansas City (9703)