The Blair Witch Project

| The Blair Witch Project | |

|---|---|

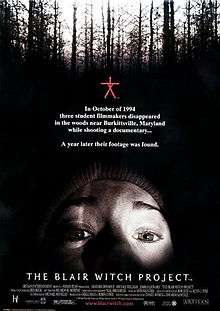

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Starring | |

| Music by | Antonio Cora |

| Cinematography | Neal Fredericks |

| Edited by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Artisan Entertainment |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 81 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $60,000[2] |

| Box office | $248.6 million[2] |

The Blair Witch Project is a 1999 American found footage psychological horror film written, directed and edited by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez. The film tells the fictional story of three student filmmakers (Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams and Joshua Leonard) who hike in the Black Hills near Burkittsville, Maryland in 1994 to film a documentary about a local legend known as the Blair Witch. The three disappear, but their video and sound equipment (along with most of the footage they shot) is discovered a year later; the "recovered footage" is the film the viewer is watching.[3]

While the film received unexpected acclaim from critics, audience reception was polarized.[4] It became a resounding box office success–grossing over US$248 million worldwide,[5] making it one of the most successful independent films of all time. The DVD was released on October 26, 1999 and, in 2010, a Blu-ray edition was released.

A sequel was released on October 27, 2000 titled Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2. Another sequel was planned for the following year, but did not materialize. On September 2, 2009, it was announced that Sánchez and Myrick were pitching the third film.[6] A trilogy of video games based on the films was released in 2000. The Blair Witch franchise has since expanded to include various novels, dossiers, comic books and additional merchandise.

On July 22, 2016, an official trailer for a sequel to the film, directed by Adam Wingard and entitled Blair Witch, was released at San Diego Comic-Con. The film, produced by Lionsgate, was released on September 16, 2016.[7] Blair Witch is a direct sequel to The Blair Witch Project, and does not acknowledge the events of Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2. However, Wingard has said that although Blair Witch does not reference any of the events that transpired in Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, the film does not necessarily discredit the existence of Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2.[8]

Fictional legend

The backstory for the movie is a legend fabricated by Sánchez and Myrick which is detailed in The Curse of the Blair Witch, a mockumentary broadcast on the SciFi Channel in 1999 prior to the release of The Blair Witch Project.[9] Sánchez and Myrick also maintain a website which adds further details to the legend.[10]

The legend describes the killings and disappearances of some of the residents of Blair, Maryland (a fictitious town on the site of Burkittsville, Maryland) from the 18th to 20th centuries. Residents blamed these occurrences on the ghost of Elly Kedward, a Blair resident accused of practicing witchcraft in 1785 and sentenced to death by exposure. The Curse of the Blair Witch presents the legend as real, complete with manufactured newspaper articles, newsreels, television news reports, and staged interviews.[9]

Plot

In October 1994, film students Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams, and Joshua Leonard set out to produce a documentary about the fabled Blair Witch. They travel to Burkittsville, Maryland, formerly Blair, and interview residents about the legend. Locals tell them of Rustin Parr, a hermit who lived in the woods, who kidnapped eight children in the 1940s. He would take the children down to his basement in pairs and make one of them stand in the corner while he killed the other one. After turning himself in to the police, Parr claimed that the spirit of Elly Kedward, a woman executed for witchcraft in the 18th century, had forced him to commit the murders. The students then interview Mary Brown, a Burkittsville resident deemed insane by the public. She claims to have encountered the Blair Witch in person, describing her as a hairy half-human, half-animal beast.

On their second day, the students explore the woods in north Burkittsville to research the legend. Along the way, they meet two fishermen, one of whom warns them that the woods are haunted and recalls that in 1888, a young girl named Robin Weaver went missing, and when she returned three days later, she talked about "an old woman whose feet never touched the ground." His companion is, however, skeptical of the story. The students then hike to Coffin Rock, where five men were found ritualistically murdered in the 19th century, their bodies later disappearing. The group then camps for the night.

The next day they move deeper into the woods despite being uncertain of their location. They eventually locate what appears to be an old cemetery with seven small cairns. They set up camp nearby and then return to the cemetery after dark. Josh accidentally disturbs a cairn and Heather hastily repairs it. Later that night, they hear the sound of twigs snapping from all directions but assume the noises are from animals or locals.

On day three, they attempt to hike back to the car, but are unable to find it before dark, much to their frustrations, and again set camp. That night, they again hear twigs snapping but fail to find the source of the noises.

On the fourth day they find three cairns have been built around their tent during the night, which unnerves them. As they continue, Heather realizes her map is missing, and Mike later reveals he kicked it into a creek the previous day out of frustration, which prompts Heather and Josh to attack him in a rage. They realize they are now lost and decide simply to head south. They eventually reach a section where they discover a multitude of humanoid stick figures suspended from trees, which further unnerves them. That night they hear sounds again, but this time includes the sounds of children laughing among other strange noises. When an unknown force shakes the tent, they flee in a panic and hide in the woods until dawn.

Upon returning to their tent, they find that their possessions have been rifled through, and Josh's equipment is covered with a translucent slime. As they continue, they begin to show signs of mentally giving up, and it is made worse when they come across a log on a river identical to one they crossed earlier. They realize they have walked in a circle, despite having traveled south all day, and once again make camp, completely demoralized at having wasted an entire day. Josh suffers a mental breakdown while holding the camera, taunting Heather for their circumstances and her constant recording of the events.

On the sixth morning, Heather and Mike awaken to find that Josh has disappeared. After trying in vain to find him, they slowly move on. That night, they hear Josh's agonized screams in the darkness but are unable to locate him. Mike and Heather theorize that Josh's screams are a fabrication by the witch in order to draw them out of their tent.

During their next day in the woods, Heather discovers a bundle of sticks tied with a piece of fabric from Josh's shirt outside her tent. As she searches through it she finds blood-soaked scraps of Josh's shirt as well as teeth, hair, and what appears to be a piece of Josh's tongue. Although distraught by the discovery, she chooses not to tell Mike. That night, Heather records herself apologizing to her family, as well as to the families of Mike and Josh, taking full responsibility for their current predicament. She then breaks down and hyperventilates, realizing that something terrible is hunting them, and will ultimately take them.

Afterward, they again hear Josh's agonized cries for help and follow them to a derelict, abandoned house containing runic symbols and children's bloody hand-prints on the walls. Mike races upstairs in an attempt to find Josh while Heather follows. Both are still filming all their actions. Mike then says he hears Josh in the basement. He runs downstairs while a hysterical Heather struggles to keep up. Upon reaching the basement, something attacks Mike, and causes him to drop the camera and go silent. Heather enters the basement screaming. Her camera captures Mike facing a corner. Something then attacks Heather, causing her to drop her camera and go silent as well. The footage then ends.

Cast

- Heather Donahue as a fictionalized version of herself.

- Michael C. Williams as a fictionalized version of himself.

- Joshua Leonard as a fictionalized version of himself.

Production

Development

The Blair Witch Project was developed during 1993[11] by the filmmakers. Myrick and Sanchez came across the idea for the film after realizing that they found documentaries on paranormal phenomena scarier than traditional horror films. The two decided to create a film that combined the styles of both.[12] The script began with a 35-page outline, with the dialogue to be improvised.[11] Accordingly, the directors advertised in Backstage magazine for actors with strong improvisational abilities.[13] There was a very informal improvisational audition process to narrow the pool of 2,000 actors.[14][15] In developing the mythology behind the movie, the filmmakers used many inspirations. Several character names are near-anagrams; Elly Kedward (The Blair Witch) is Edward Kelley, a 16th-century mystic. Rustin Parr, the fictional 1940s child-murderer, began as an anagram for Rasputin.[16] In talks with investors, they presented an eight-minute documentary along with newspapers and news footage.[17] This documentary, originally called The Blair Witch Project: The Story of Black Hills Disappearances was produced by Haxan Films.

Casting

According to Heather Donahue, auditions for the film were held at Musical Theater Works in New York City, and ads were placed in the weekly Backstage for an open audition.[18] The advertisement noted an "entirely improvised feature film" shot in a "wooded location."[18] Donahue described the audition as Myrick and Sanchez posing her the question: "You've served seven years of a nine year sentence. Why should we let you out on parole?" to which Donahue was required to improvise a response.[18]

Joshua Leonard, also in response to audition calls through Back Stage, claimed he was cast in the film due to his knowledge of how to run a camera, as there was not an omniscient camera filming the scenes.[19]

Filming

Filming began in October 1997 and lasted eight days.[13][20] Most of the movie was filmed in Seneca Creek State Park in Montgomery County, Maryland, although a few scenes were filmed in the real town of Burkittsville.[21] Some of the townspeople interviewed in the film were not actors, and some were planted actors, unknown to the main cast. The final scenes were filmed at the historic Griggs House in Granite, Maryland. Donahue had never operated a camera before and spent two days in a "crash course." Donahue said she modeled her character after a director she once worked with, citing the character's self assuredness when everything went as planned, and confusion during crisis.[22]

During filming, the actors were given clues as to their next location through messages given in milk crates found with Global Positioning Satellite systems. They were given individual instructions that they would use to help improvise the action of the day.[13] Teeth were obtained from a Maryland dentist for use as human remains in the movie.[13] Influenced by producer Gregg Hale's memories of his military training, in which "enemy soldiers" would hunt a trainee through wild terrain for three days, the directors moved the characters a long way during the day, harassing them by night and depriving them of food.[17]

Almost 19 hours of usable footage was recorded which had to be edited down to 90 minutes.[15] The editing in post production took more than eight months. Originally it was hoped that the movie would make it on to cable television, and the filmmakers did not anticipate wide release.[11] The initial investment by the three filmmakers was about US$35,000. Artisan acquired the film for US$1.1 million but spent US$25 million to market it. The actors signed a "small" agreement to receive some of the profits from the film's release.[13]

A list of production budget figures have circulated over the years, appearing as low as $20,000. In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, Sánchez revealed that when principal photography first wrapped, approximately $20,000 to $25,000 had been spent.[23] Other figures list a final budget ranging between $500,000 and $750,000.[24]

Promotion

The Blair Witch Project is thought to be the first widely released movie marketed primarily by internet. The movie's official website featured fake police reports and "newsreel-style" interviews. These augmented the movie's found footage device to spark debates across the internet over whether the movie was a real-life documentary or a work of fiction.[25][26] During screenings of the movie, the filmmakers made advertising efforts to promulgate the events in the film as factual, including the distribution of flyers at festivals such as the Sundance Film Festival, asking viewers to come forward with any information about the "missing" students.[27][28][29] The campaign tactic was that viewers were being told, through missing persons posters, that the filmmakers were missing while researching in the woods for the mythical Blair Witch.[30] The IMDb page also listed the actors as "missing, presumed dead" in the first year of the film's availability.[29][31] The film's website contained materials of actors posing as police and investigators giving testimony about their casework, and shared childhood photos of the actors to add a sense of realism.[32]

USA Today has opined that the movie was the first movie to go "viral" despite having been produced before many of the technologies that facilitate such phenomena existed.[33]

Reception

Box office

The Blair Witch Project was shown at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival and had a limited release on July 14, before going wide on July 30, 1999 after months of publicity, including a campaign by the studio to use the Internet and suggest that the movie was a record of real events. The distribution strategy for The Blair Witch Project was created and implemented by Artisan studio executive Steven Rothenberg.[34][35]

The Blair Witch Project grossed $248.6 million worldwide.[36] After reshoots, a new sound mix, experiments with different endings and other changes made by the studio, the film's final budget ended up between $500,000 and $750,000.[24]

Critical response

The film received wide acclaim from critics, although audience reception was polarized and divided.[4] Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an approval rating of 86%, based on 155 reviews, with an average rating of 7.7/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Full of creepy campfire scares, mock-doc The Blair Witch Project keeps audiences in the dark about its titular villain -- thus proving that imagination can be as scary as anything onscreen."[37] On Metacritic the film has a score of 81 out of 100, based on 33 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[38]

The film's "found footage" format received near-universal praise by critics and, though not the first in the found footage device, the film has been declared a milestone in film history due to its critical and box office success. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun Times gave the film a total of 4 stars, calling it "an extraordinarily effective horror film".[39] It was listed on Filmcritic.com as the 50th best movie ending of all time.[40]

Film critic Michael Dodd has argued that the film is an embodiment of horror "modernizing its ability to be all-encompassing in expressing the fears of American society", acknowledging its status as the archetypal modern found footage feature, he noted that "In an age where anyone can film whatever they like, horror needn’t be a cinematic expression of what terrifies the cinema-goer, it can simply be the medium through which terrors captured by the average American can be showcased".[41] During 2008, Entertainment Weekly named The Blair Witch Project one of "the 100 best films from 1983 to 2008", ranking it at #99.[42] In 2006, Chicago Film Critics Association listed it as one of the "Top 100 Scariest Movies", ranking it #12.[43]

Because the filming was done by the actors using hand-held cameras, much of the footage is shaky, especially the final sequence in which a character is running down a set of stairs with the camera. Some audience members experienced motion sickness and even vomited as a result.[44]

Awards and honors

The Blair Witch Project was nominated for, and won, the following awards.

| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Film Critics Award[45] | Best Screenplay | Daniel Myrick | Nominated |

| Eduardo Sánchez | Nominated | ||

| Independent Spirit John Cassavetes Award | Best Film | Won | |

| Golden Raspberry Award | Worst Picture | Robin Cowie | Nominated |

| Gregg Hale | Nominated | ||

| Worst Actress | Heather Donahue | Won | |

| Stinkers Bad Movie Awards[46] | Worst Picture | Robin Cowie | Nominated |

| Gregg Hale | Nominated | ||

| Worst Actress | Heather Donahue | Nominated | |

| Biggest Disappointment | Won | ||

| Worst Screen Debut | Heather, Michael, Josh, the Stick People and the world's longest running batteries | Nominated | |

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2001: AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – Nominated[47]

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- The Blair Witch – Nominated Villain[48]

Cinematic and literary allusions

In the movie, the Blair Witch is, according to legend, the ghost of Elly Kedward, a woman banished from the Blair Township (latter-day Burkittsville) for witchcraft in 1785. The directors incorporated that part of the legend, along with allusions to the Salem Witch Trials and The Crucible, to play on the themes of injustice done on those who were called witches.[14] They were influenced by The Shining, Alien, The Omen and Benjamin Christensen's 1922 silent documentary Häxan, after which the producers named their production company, Haxan Films. Jaws was an influence as well, presumably because the witch was hidden from the viewer for the entirety of the film, forcing suspense from the unknown.[11]

Soundtrack

None of the songs featured on Josh's Blair Witch Mix actually appear in the movie. However, "The Cellar" is played during the credits and the DVD menu. This collection of mostly goth rock and industrial tracks is supposedly from a mix tape made by ill-fated film student Joshua Leonard. In the story, the tape was found in his car after his disappearance. Some of the songs featured on the soundtrack were released after 1994, after the events of the movie supposedly have taken place. Several of them feature dialogue from the movie as well.

- "Gloomy Sunday" – Lydia Lunch

- "The Order of Death" – Public Image Ltd.

- "Draining Faces" – Skinny Puppy

- "Kingdom's Coming" – Bauhaus

- "Don't Go to Sleep Without Me" – The Creatures

- "God Is God" – Laibach

- "Beware" – The Afghan Whigs

- "Laughing Pain" – Front Line Assembly

- "Haunted" – Type O Negative

- "She's Unreal" – Meat Beat Manifesto

- "Movement of Fear" – Tones on Tail

- "The Cellar" – Antonio Cora

Media tie-ins

Books

In September 1999, D.A. Stern compiled The Blair Witch Project: A Dossier. Perpetuating the film's "true story" angle, the dossier consisted of fabricated police reports, pictures, interviews, and newspaper articles presenting the movie's premise as fact, as well as further elaboration on the Elly Kedward and Rustin Parr legends (an additional "dossier" was created for Blair Witch 2). Stern wrote the 2000 novel Blair Witch: The Secret Confessions of Rustin Parr and in 2004, revisited the franchise with the novel Blair Witch: Graveyard Shift, featuring all original characters and plot.

In May 1999, a Photonovel adaptation of The Blair Witch Project was written by Claire Forbes and was released by Fotonovel Publications.

The Blair Witch Files

A series of eight young adult books entitled The Blair Witch Files were released by Random subsidiary Bantam from 2000 to 2001. The books center on Cade Merill, a fictional cousin of Heather Donahue, who investigates phenomena related to the Blair Witch in attempt to discover what really happened to Heather, Mike, and Josh.[49]

- The Blair Witch Files 1 – The Witch's Daughter

- The Blair Witch Files 2 – The Dark Room

- The Blair Witch Files 3 – The Drowning Ghost

- The Blair Witch Files 4 – Blood Nightmare

- The Blair Witch Files 5 – The Death Card

- The Blair Witch Files 6 – The Prisoner

- The Blair Witch Files 7 – The Night Shifters

- The Blair Witch Files 8 – The Obsession

Comic books

In August 1999, Oni Press released a one-shot comic promoting the film, simply titled The Blair Witch Project. Written by Jen Van Meter and drawn by Bernie Mireault, Guy Davis, and Tommy Lee Edwards, the comic featured three short stories elaborating on the mythology of the Blair Witch. In mid-2000, the same group worked on a four-issue series called The Blair Witch Chronicles.

In October 2000, coinciding with the release of Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, Image Comics released a one-shot called Blair Witch: Dark Testaments, drawn by Charlie Adlard and written by Ian Edginton.

Video games

In 2000, Gathering of Developers released a trilogy of computer games based on the film, which greatly expanded on the myths first suggested in the film. The graphics engine and characters were all derived from the producer's earlier game Nocturne.[50] Each game, developed by a different team, focused on different aspects of the Blair Witch mythology: Rustin Parr, Coffin Rock, and Elly Kedward, respectively.

The trilogy received mixed reviews from critics, with most criticism being directed towards the very linear gameplay, clumsy controls and camera angles, and short length. The first volume, Rustin Parr, received the most praise, ranging from moderate to positive, with critics commending its storyline, graphics and atmosphere; some reviewers even claimed that the game was scarier than the movie.[51] The following volumes were less well-received, with PC Gamer saying that Volume 2's only saving grace was its cheap price[52] and calling Volume 3 "amazingly mediocre".[53]

Documentary

The Woods Movie (2015) is a feature-length documentary exploring the production of The Blair Witch Project.[54] For this documentary, director Russ Gomm interviewed the original film's producer, Gregg Hale, and directors, Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick.[55]

Home media

The Blair Witch Project was released on DVD on October 26, 1999, with VHS and laserdisc versions released around the same time. The DVD included a number of special features, including "The Curse of the Blair Witch" and "The Blair Witch Legacy" featurettes, newly discovered footage, director and producer commentary, production notes, cast & crew bios, and trailers.

A Blu-ray release from Lionsgate was released on October 5, 2010.[56] Best Buy and Lionsgate had an exclusive release of the Blu-ray available on August 29, 2010.[57]

Sequels

A sequel, Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, was released in the autumn of 2000. The film was poorly received by most critics.[58] A third installment announced that same year did not materialize.[59]

In January 2015, Eduardo Sanchez revealed that he was still planning Blair Witch 3 and that he considered the film "inevitable", but added that there was nothing to officially announce at that time.[60]

On July 22, 2016, a surprise trailer of Blair Witch, directed by Adam Wingard, a sequel to the first film, was released at San Diego Comic-Con.[61] The film was originally marketed as The Woods so as to be an exclusive surprise announcement for those in attendance at the convention. The film, produced by Lionsgate, is slated for a September 16, 2016 release[7] and stars James Allen McCune as the brother of the original film's Heather Donahue.[62] In September 2016, screenwriter Simon Barrett explained that in writing the new film he only considered material that was produced with the involvement of the original film's creative team (directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez, producer Greg Hale, and production designer Ben Rock) to be "canon", and that he did not take any material produced without their direct involvement—such as the first sequel Book of Shadows or The Blair Witch Files, a series of young adult novels—into consideration when writing the new sequel.[8]

An unofficial spin-off was released in 2011 titled Doc. 33, an Italian found footage horror film directed by 22-years-old director Giacomo Gabrielli. The film starts by describing the events that occur in The Blair Witch Project; it then follows by describing a similar incident that occurred in Wirgen, Austria. The film revolves around a group of filmmakers in 1998 who investigate an orphanage in the woods where dozens of children were murdered by nuns. The nuns took part in occult practices which dubbed the Mother Superior of the orphanage "The Witch of Wirgen Woods."

See also

- List of ghost films

- Found footage (pseudo-documentary)

- The Bogus Witch Project, a direct-to-video parody.

Literature

- Schreier, Margrit (2004): Please Help Me; All I Want to Know Is: Is It Real or Not? How Recipients View the Reality Status of The Blair Witch Project. In: Poetics Today, Vol. 25, Nr. 2, pp. 305–334 (full text, qualitative content analysis on the movie´s reception)

References

- ↑ "The Blair Witch Project (15)". British Board of Film Classification. August 4, 1999. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- 1 2 "The Blair Witch Project". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Editorial: Paranormal Activity Shadows The Blair Witch". DreadCentral.

- 1 2 "The Blair Witch Project is getting a proper sequel". TechnoBuffalo. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ "The Blair Witch Project". Box Office Mojo.com. 2006-01-01. Retrieved 2006-07-28.

- ↑ Geoghegan, Kev (2009-08-11). "The legend of the Witch lives on". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- 1 2 Woerner, Meredith. "'Blair Witch' sequel surprises Comic-Con with a secret screening and trailer". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- 1 2 "Why The New Blair Witch Movie Ignores Book Of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 - CINEMABLEND". September 14, 2016.

- 1 2 "Curse of the Blair witch". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ "The Blair Witch". Archived from the original on July 7, 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Klein, Joshua (July 22, 1999). "Interview - The Blair Witch Project". avclub.com. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ↑ Bowies, Scott. "'Blair Witch Project': Still a legend 15 years later". USA Today. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Staff (January 1, 1999). "Heather Donohue – Blair Witch Project". KAOS 2000 Magazine. Retrieved July 30, 2006.

- 1 2 Aloi, Peg (July 11, 1999). "Blair Witch Project – an Interview with the Directors". Witchvox.com. Retrieved July 29, 2006.

- 1 2 Mannes, Brett (July 13, 1999). "Something wicked". Salon.com. Retrieved July 29, 2006.

- ↑ Blake, Scott (Jul 17, 2007). "An Interview With The Burkittsville 7's Ben Rock". IGN.com. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- 1 2 Conroy, Tom (July 14, 1999). "The Do-It-Yourself Witch Hunt". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2006.

- 1 2 3 Donahue, Heater. Interview with Craig Kilborn. CBS Networks. August 1999.

- ↑ Loewenstein, Melinda (March 16, 2013). "How Joshua Leonard Fell In Love With Moviemaking". Backstage. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Corliss, Richard (August 16, 1999). "Blair Witch Craft". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ↑ Kaufman, Anthony (July 14, 1999). "Season of the Witch". Village Voice. Archived from the original on March 3, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ↑ Lim, Dennis (July 14, 1999). "Heather Donahue Casts A Spell". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on December 4, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- ↑ John Young. "'The Blair Witch Project' 10 years later: Catching up with the directors of the horror sensation". Entertainment Weekly.

- 1 2 John Young (July 9, 2009). "'The Blair Witch Project' 10 years later: Catching up with the directors of the horror sensation". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- ↑ Weinraub, Bernard (August 17, 1999). "Blair Witch Proclaimed First Internet Movie". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- ↑ Weinraub, Bernard (October 30, 2015). "Was The Blair Witch Project The Last Great Horror Film?". BBC News. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ "IMDb: The Blair Witch Project".

- ↑ "Editorial: The 12 Ballsiest Movie Publicity Stunts".

- 1 2 "The Blair Witch Project: The best viral marketing campaign of all time".

- ↑ Amelia River (July 11, 2014). "The Greatest Movie Viral Campaigns". Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ "The Blair Witch Project".

- ↑ "The Blair Witch Project Official Website: The Filmmakers".

- ↑ Bowies, Scott. "'Blair Witch Project': Still a legend 15 years later". USA Today. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ DiOrio, Carl (July 19, 2009). "Steve Rothenberg dies at age 50". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ↑ McNary, Dave (July 20, 2009). "Lionsgate's Steven Rothenberg dies". Variety Magazine. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ↑ "The Blair Witch Project". Box Office Mojo.com. January 1, 2006. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ↑ "The Blair Witch Project". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ↑ "The Blair Witch Project".

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (July 16, 1999). "The Blair Witch Project". Roger Ebert.com. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ↑ Null, Christopher (January 1, 2006). "The Top 50 Movie Endings of All Time". filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006. Retrieved July 30, 2006.

- ↑ "Safe Scares: How 9/11 caused the American Horror Remake Trend (Part One)". August 31, 2014.

- ↑ "The New Classics: Movies – EW 1000: Movies – Movies – The EW 1000 – Entertainment Weekly". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Scariest Movies Ever Made: Chicago Critics' Top 100".

- ↑ Wax, Emily (July 30, 1999). "The Dizzy Spell of 'Blair Witch Project'". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- ↑ "www.globalfilmcritics.com". www.globalfilmcritics.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ↑ "1999 22nd Hastings Bad Cinema Society Stinkers Awards". Stinkers Bad Movie Awards. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ↑ Merill, Cade (2000). "Cade Merill's The Blair Witch Files". Random House. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ↑ Smith, Jeff. 'Blair Witch Project Interview' IGN.com. April 14, 2000.

- ↑ 'Metacritic: Blair Witch Volume 1: Rustin Parr'. Metacritic.

- ↑ 'Metacritic – Blair Witch Volume 2' Metacritic.

- ↑ 'Metacritic – Blair Witch Volume 3' Metacritic.

- ↑ "Blair Witch Documentary Goes into The Woods Movie". DC. January 1, 2006. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ↑ "Finally a Doc On 'The Blair Witch Project' – Trailer For "The Woods Movie"". DC. January 1, 2006. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ↑ "The Blair Witch Project Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- ↑ "The Blair Witch Project". High Def Digest. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ↑ B., Scott (August 21, 2001). "Blair Witch Project 3 to Happen?". IGN.com. Retrieved July 30, 2006.

- ↑ "Blair Witch 3". Yahoo Movies. 2006-01-01. Archived from the original on 2006-05-09. Retrieved 2006-07-28.

- ↑ Barton, Steve (January 14, 2015). "Eduardo Sanchez Talks Blair Witch 3". dreadcentral.com. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=girSv9UH_V8 Blair Witch trailer

- ↑ Collis, Clark. "Secret Blair Witch sequel gets new trailer, September release date". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Blair Witch Project |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Blair Witch Project. |

- Official website

- The Blair Witch Project at the Internet Movie Database

- The Blair Witch Project at AllMovie

- The Blair Witch Project at Box Office Mojo

- The Blair Witch Project at Rotten Tomatoes