The Cartel

| The Cartel | |

|---|---|

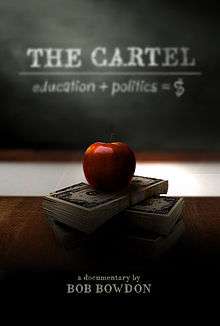

Official poster | |

| Directed by | Bob Bowdon |

| Produced by | Jen Wekelo |

| Written by | Bob Bowdon |

| Edited by |

Morgan Beatty Vinny Randazzo Dave Wittlin Sam Wolfson |

Production company |

Bowdon Media with the Moving Picture Institute |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The Cartel is a 2009 American documentary film by New Jersey-based television producer, reporter and news anchor Bob Bowdon, that covers the failures of public education in the United States by focusing on New Jersey, which has the highest level of per-student education spending in the U.S.[1] According to The Internet Movie Database (IMDb), the film asks: "How has the richest and most innovative society on earth suddenly lost the ability to teach its children at a level that other modern countries consider 'basic'?"[2] The film regards teachers' unions as the cause of the problems (they are "the cartel" of the title), due to, among other things, the obstacles they put in place to firing bad teachers, through tenure. It also makes the case for school vouchers and charter schools,[3] suggesting that the increased competition will revitalize the school system, leading to improved efficiency and performance in all schools, both district and charter.

The film debuted at the Hoboken International Film Festival on May 30, 2009 and was awarded "Best of the Festival (Audience Award)".[4] It opened in New York City and Los Angeles on April 16, 2010, Houston on April 23 and in Denver, Minneapolis, Boston, Washington D.C., St. Louis, San Francisco, Philadelphia and Chicago on April 30.

The Cartel is Bowdon's first film; he left Bloomberg Television to focus on the project, and spent two years on it.[3] The film's post production was aided by the Moving Picture Institute.

Film content

Bowdon interviewed "school administrators, teachers, parents, students and education advocates" for the film.[3] Among the interviews are State Education Commissioner Lucille Davy, Clint Bolick (former president of Alliance for School Choice), Gerard Robinson (president of Black Alliance for Educational Options), and Chester Finn (president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute).[1]

Administrative waste

The film highlights the problem of waste and corruption in the New Jersey public school system that Bowdon claims is rampant in districts throughout the country. He chooses the New Jersey area as it serves as an example of what can happen when problems are addressed by allocating more budget money to a problem rather than attempting to find and correct the problem directly. The alleged administrative inefficiency present in New Jersey is highlighted by Bowden's comparison of the state's educational system to that of another state that Bowden explains is chosen because it is nearby and similarly populated, Maryland. On average, Maryland has one school district for 35,000 students, whereas New Jersey has 15 school districts for the same number of students.

During 2008 budget crisis, while many other departments were "on the chopping block" (proposed budget had 4B in cuts), the teacher's union successfully lobbied for a 5% increase in education spending.

Construction costs and related corruption also represent a major cost according to Bowden. The New Jersey School Construction Corporation (SCC), now known as the New Jersey Schools Development Authority (NJSDA), which was responsible for the managing of construction of schools and educational infrastructure in the state allegedly didn't have any set budget, and was not monitored effectively by any other body; as a result, it is alleged that the organization "lost" between $500 million and $1 billion without a trace to poor accounting.

Bowden points out Malcolm X Shabazz High School, which he describes as one of the many under-performing schools in the state, which spent 6 million dollars on constructing a brand new "state of the art" football field,[5] rather than spending the same money to improve academics.

Inability to remove poor-performing teachers

Another major problem with the public school system according to Bowden is the difficulty with firing tenured teachers, seemingly no matter how bad they are. Rules originally put in place by the teacher's unions to protect teachers, he argues, have come to hinder fairness and accountability and actually hurt good teachers by keeping bad ones in place. He cites as one example an illiterate high school teacher in California who taught for seventeen years, relying upon the help of "student aides" to do the necessary in-class reading and writing for him.[6]

During her interview, the head of the New Jersey Education Association (NJEA) Joyce Powell responded to criticisms of the tenure process: when presented with a statistic that only 0.03% of tenured teachers are removed from the classroom, she suggested that this was true because 99.97% are "doing a good job," saying "I think 99.97% should be celebrated."[7]

Performance of charter schools

As a counterpoint to all of these types of problems, Bowden suggests that the increased prevalence of charter schools which compete for students and government funding with public schools will have the effect of improving quality and efficiency across the board. Students at charter schools have been shown to frequently perform better than their counterparts in the same areas; some assume that this is the case because they admit better-performing students to begin with, but many, like the North Star Academy Charter School, select students by random lottery, often with incoming students who perform slightly lower than the district average. North Star, as an example, spends 25% less per student, even without the large economies of scale of the large district.

8th graders of the Robert Treat Academy Charter School achieved far higher proficiency rates than students in the Newark District school on the 2007 GEPA at a far lower cost per student: 88.4% to 49.9% in language arts; 93.0% to 35.3% in math; with $10,994 versus $17,237 of spending per student, respectively.

Bowden also notes examples of charters that don't outperform district schools in their same area, like the Hope Academy, which scored far lower in language arts and math proficiency (27.8 to 21.4% in language arts, 19.6 to 14.3% in math), but says that parents will often still prefer charters, simply to get their children out of dangerous situations that exist in the public schools. One Hope Academy student describes his old school as being "just like" the school in the film Lean on Me, "before Joe Clark came in."

Perhaps the most major hindrance to the creation of charter schools, he suggests, is that the New Jersey Department of Education (NJ DOE) has the sole power to approve or deny charter school applicants, and in 2008, approved just one out of 22. They are not required to give applicants any reasons for denial, but applicants interviewed in the film allege that they were denied on seemingly trivial mistakes in their lengthy applications.

The street interviews Bowden conducted indicate that people invariably support the increased funding of schools under the understanding that increased funding will improve the quality of education in the United States; Bowden, on the other hand, argues that efficiency and quality is best achieved through competition of resources which demands that efficiency and quality be achieved in order to thrive and attract "customers". While people commonly cite the concern that charter schools will take away funding to the detriment of the public school system, Bowden argues that they will benefit as much as anyone else from the competition and perhaps, smaller classroom sizes.

The film credits include the reminder, "There are good teachers in the worst schools. There are good administrators in the worst districts. Support them! (While you fight The Cartel).

Controversy

The NJEA called The Cartel "an orchestrated attack against public schools and the New Jersey Education Association (NJEA)." Furthermore, the NJEA stated that Bowdon and his crew failed to identify their "true agenda" when interviewing Powell, instead questioning her under false pretenses of an "independent 'documentary on public education in New Jersey,' with a focus on No Child Left Behind, the state school funding law, and charter schools."[8]

Bowdon said that the NJEA invented the fact that the film had had any financial support before it was completely finished, and that his partnerships and financial support were all post production. He said that rather than addressing any of the film's substantive arguments, they focused instead on personal attacks at him. He also said, "It's more than a little ironic that the NJEA criticized me for lack of transparency through an anonymous author."

Davy said that some issues raised by The Cartel, particularly superintendents' contracts, were already addressed with new accountability regulations.[3]

Reception

Wesley Morris of The Boston Globe wrote, "as is the wont of certain TV news reporting, his approach pre-chews every detail, lest we fail to understand it. He’s smart. We’re dumb. Let the animated inserts explain the facts." He added, "it’s a testament to how fascinatingly bad things are for our public schools that 'The Cartel' is as watchable as it is."[9]

Brian MacQuarrie of the Boston Globe says that in The Cartel, "the causes and consequences of the failings of public education are chronicled in extraordinary detail."[10]

Amy Biancolli of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, "There's no history offered. Not a peep about No Child Left Behind. What's more, there's no breakdown of urban Jersey's demographics - the percentage of kids on school lunch aid, perhaps? - or any attempt to link classroom woes with urban problems. Yet even these gaps wouldn't have doomed the movie if Bowdon had sexed it up with a bit of old-fashioned cinematic salesmanship. The film plays more like a 90-minute TV special than a feature release. It's all talking heads, clanging music, substandard graphics, long scans of Web-page headlines and Bowdon's heavily cadenced voiceovers."[11]

Matt Pais of the website Metromix wrote, "Bowdon would have something if he scaled back the outrage and analyzed the causes of these practices and, ultimately, why so many children around the country aren’t being properly taught. Instead the filmmaker tries to position New Jersey as a microcosm of America and turns “The Cartel” into a local news report that goes on forever."[12]

Kyle Smith of the New York Post writes, "For parents of kids in public schools, the heartbreaking documentary "The Cartel" is a revelation," and that "few documentaries have covered such an important matter so convincingly and with such clarity. When it comes to public education, we are all New Jerseyans."[13]

The Los Angeles Times' Kevin Thomas calls the film a "brisk, incisive and mind-boggling — no other phrase will work — exposé of his native New Jersey's public education system," saying that "Bowdon moves beyond statistics to discover how the sorry condition of his state's public schools came to be."[14]

Impact

New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, who came into office in 2010, saw the movie before being elected, and said that it "helped to mold for me the final outlines of what I wanted to do if I were lucky enough to become governor." He praised that documentary, as well as Waiting for "Superman", which came out after he was already governor. In another interview, he said that the film was "extraordinarily important" in that it tells a story about what is going on in the New Jersey public school system that "needs to be told."[15]

References

- 1 2 http://www.thecartelmovie.com/cgi-local/content.cgi?g=20

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1433001/

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/2009/05/nj_educational_system_examined.html

- ↑ http://www.hobokeninternationalfilmfestival.com/

- ↑ "Malcolm X. Shabazz Athletic Facility". Yu & Associates Geotechnical, Environmental and Civil Engineering. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ Yau, Margaret. "OCEANSIDE: Teacher who beat illiteracy marks 15th anniversary of tutoring program". Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ http://www.dailyrecord.com/article/20090826/COLUMNISTS01/90825044/1100/NEWS01/A+film+about+N.J.+s+education+

- ↑ http://www.njea.org/page.aspx?a=4149

- ↑ Morris, Wesley (April 30, 2010). "The Cartel: A digestible lesson in public-school failures". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ MacQuarrie, Brian. "'The Cartel' sees teacher unions' grip as crippling". the Boston Globe. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ Biancolli, Amy (April 30, 2010). "Review: 'The Cartel' rates a failing grade". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Pais, Matt (April 29, 2010). "'The Cartel' review". Metromix New York.

- ↑ Smith, Kyle. "NJ paradox: Piles of cash, failing schools". New York Post. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ Thomas, Kevin. "Capsule Movie Reviews: 'The Cartel' examines a state falling down on the job in educating its children". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ Chris Christie Comments on The Cartel Movie -- Extended Cut on YouTube