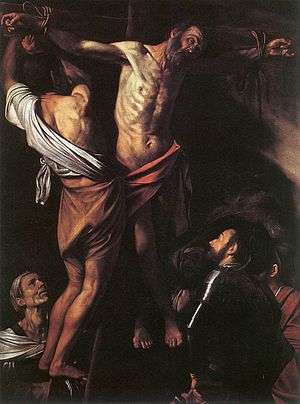

The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew (Caravaggio)

| Italian: La Crocifissione di Sant' Andrea, Spanish: La Crucifixión de San Andrés | |

| |

| Artist | Caravaggio |

|---|---|

| Year | 1607 |

| Medium | oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 202.5 cm × 152.7 cm (79.7 in × 60.1 in) |

| Location | Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio |

The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew (1607) is a painting by the Italian Baroque master Caravaggio. It is in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, which acquired it from the Arnaiz collection in Madrid in 1976, having been taken to Spain by the Spanish Viceroy of Naples in 1610.

The incident depicted, the martyrdom of Saint Andrew, was supposed to have taken place in Patras, Greece. The saint, bound to the cross with ropes, was said to have survived two days, preaching to the crowd and eventually converting them so that they demanded his release.[1] When the Roman Proconsul Aegeas[2] - depicted lower right - ordered him taken down, his men were struck by a miraculous paralysis, in answer to the saint's prayer that he be allowed to undergo martyrdom.[3]

From the 17th century Saint Andrew was shown on a diagonal cross, but Caravaggio would have been influenced by the 16th century belief that he was crucified on a normal Latin cross.

History

On 11 July 1610 Juan Alonso Pimentel de Herrera, 5th Duke of Benavente, left Naples for Spain, having served as viceroy of that city for seven years. With him he a took a painting Giovanni Pietro Bellori described as "la Crocifissione di Santo Andrea".[4][5] The painting was installed at the family palace in Valladolid, where it was appraised, in 1653,[lower-alpha 1] at 1,500 ducats, by far the highest value painting in the family collection.[6] The occasion for the appraisal came with the death of the 7th Duke of Benavente in December 1652.

The appraiser was Diego Valentín Díaz who described the work as "a large painting of a nude St Andrew when he is being put on the cross with three executioners and a woman, with an ebony frame"[lower-alpha 2] and it is attributed to "micael angel caraballo". This painting was almost certainly commissioned by the viceroy, who was especially devoted to Saint Andrew and played a role in renovating the crypt of Saint Andrew in the Amalfi Cathedral.[2]

The Valladolid painting is thought to be the same as the present work, acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1976. There are three other versions of the composition, considered to be copies: one formerly of the Back-Vega collection of Vienna,[7] another at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, and a third at the Museum of Santa Cruz, Toledo.[6] This specific version was first given to Caravaggio by Benedict Nicolson in 1974.[8]

Notes

References

- ↑ In Monumenta Germaniae Historica II, cols. 821-847, translated in M.R. James, The Apocryphal New Testament (Oxford) reprinted 1963:369.

- 1 2 Graham-Dixon, Andrew (2011). Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9780241954645.

- ↑ Langdon, Helen (2000). Caravaggio: A Life. Westview Press. ISBN 9780813337944.

- ↑ Bellori, Giovanni (1672). Le vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti moderni. Rome: Mascardi. p. 214.

- ↑ Bellori, Giovanni Pietro (2005). Hellmut Wohl, ed. Giovanni Pietro Bellori: The Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects: A New Translation and Critical Edition. Cambridge University Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780521781879. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- 1 2 Tzeutschler Lurie, Ann; Denis Mahon (January 1977). "Caravaggio's Crucifixion of Saint Andrew from Valladolid". The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art. 64 (1): 2–24. JSTOR 25152672.

- ↑ Back-Vega, Emmerich; Christa Back-Vega (March 1958). "A Lost Masterpiece by Caravaggio". The Art Bulletin. 40 (1): 65–66. doi:10.2307/3047748. JSTOR 3047748.

- ↑ Nicolson, Benedict (October 1974). "Caravaggio and the Caravaggesques: Some Recent Research". The Burlington Magazine. 116 (859): 565, 602–616, 622. JSTOR 877821.

Bibliography

- Gash, John (2004). Caravaggio. ISBN 1-904449-22-0.

External links

Media related to Crucifixion of Saint Andrew by Caravaggio at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Crucifixion of Saint Andrew by Caravaggio at Wikimedia Commons