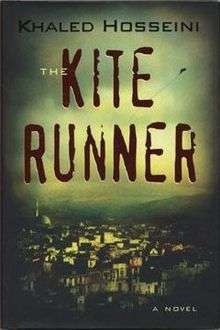

The Kite Runner

First edition cover (US hardback) | |

| Author | Khaled Hosseini |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Honi Werner |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | |

| Publisher | Riverhead Books |

Publication date | May 29, 2003 |

| Pages | 372 |

| ISBN | 1-57322-245-3 |

| OCLC | 51615359 |

| 813/.6 21 | |

| LC Class | PS3608.O832 K58 2003 |

The Kite Runner is the first novel by Afghan-American author Khaled Hosseini.[1] Published in 2003 by Riverhead Books, it tells the story of Amir, a young boy from the Wazir Akbar Khan district of Kabul, whose closest friend is Hassan, his father's young Hazara servant. The story is set against a backdrop of tumultuous events, from the fall of Afghanistan's monarchy through the Soviet military intervention, the exodus of refugees to Pakistan and the United States, and the rise of the Taliban regime.

Hosseini has commented that he considers The Kite Runner to be a father–son story, emphasizing the familial aspects of the narrative, an element that he continued to use in his later works.[2] Themes of guilt and redemption feature prominently in the novel,[3] with a pivotal scene depicting an act of violence against Hassan that Amir fails to prevent. The latter half of the book centers on Amir's attempts to atone for this transgression by rescuing Hassan's son over two decades later.

The Kite Runner became a bestseller after being printed in paperback and was popularized in book clubs. It was a number one New York Times bestseller for over two years,[4] with over seven million copies sold in the United States.[5] Reviews were generally positive, though parts of the plot drew significant controversy in Afghanistan. A number of adaptations were created following publication, including a 2007 film of the same name, several stage performances, and a graphic novel.

Composition and publication

Khaled Hosseini worked as a medical internist at Kaiser Hospital in Mountain View, California for several years before publishing The Kite Runner.[3][6][7] In 1999, Hosseini learned through a news report that the Taliban had banned kite flying in Afghanistan,[8] a restriction he found particularly cruel.[9] The news "struck a personal chord" for him, as he had grown up with the sport while living in Afghanistan. He was motivated to write a 25-page short story about two boys who fly kites in Kabul.[8] Hosseini submitted copies to Esquire and The New Yorker, both of which rejected it.[9] He rediscovered the manuscript in his garage in March 2001 and began to expand it to novel format at the suggestion of a friend.[8][9] According to Hosseini, the narrative became "much darker" than he originally intended.[8] His editor, Cindy Spiegel, "helped him rework the last third of his manuscript", something she describes as relatively common for a first novel.[9]

As with Hosseini's subsequent novels, The Kite Runner covers a multigenerational period and focuses on the relationship between parents and their children.[2] The latter was unintentional; Hosseini developed an interest in the theme while in the process of writing.[2] He later divulged that he frequently came up with pieces of the plot by drawing pictures of it.[7] For example, he did not decide to make Amir and Hassan brothers until after he had "doodled it".[7]

Like Amir, the protagonist of the novel, Hosseini was born in Afghanistan and left the country as a youth, not returning until 2003.[10] Thus, he was frequently questioned about the extent of the autobiographical aspects of the book.[9] In response, he said, "When I say some of it is me, then people look unsatisfied. The parallels are pretty obvious, but ... I left a few things ambiguous because I wanted to drive the book clubs crazy."[9] Having left the country around the time of the Soviet invasion, he felt a certain amount of survivor's guilt: "Whenever I read stories about Afghanistan my reaction was always tinged with guilt. A lot of my childhood friends had a very hard time. Some of our cousins died. One died in a fuel truck trying to escape Afghanistan [an incident that Hosseini fictionalises in The Kite Runner]. Talk about guilt. He was one of the kids I grew up with flying kites. His father was shot."[2][11] Regardless, he maintains that the plot is fictional.[8] Later, when writing his second novel, A Thousand Splendid Suns (then titled Dreaming in Titanic City), Hosseini remarked that he was happy that the main characters were women as it "should put the end to the autobiographical question once and for all".[9]

Riverhead Books published The Kite Runner, ordering an initial printing of 50,000 copies in hardback.[9][12] It was released on May 29, 2003, and the paperback edition was released a year later.[9][13] Hosseini took a year-long absence from practicing medicine to promote the book, signing copies, speaking at various events, and raising funds for Afghan causes.[9] Originally published in English, The Kite Runner was later translated into 42 languages for publication in 38 countries.[14] In 2013, Riverhead released the 10th anniversary edition with a new gold-rimmed cover and a foreword by Hosseini.[15] That same year, on May 21, Khaled Hosseini published another book called And the Mountains Echoed.

Following The Kite Runner's success, Hosseini continued to work as a physician for another year and a half before becoming a full-time writer.[16] "Medicine was an arranged marriage, writing is my mistress," he explains, employing a quote from Chekhov.[7]

Plot summary

Part I

Amir, a well-to-do Pashtun boy, and Hassan, a Hazara who is the son of Ali, Amir's father's servant, spend their days kite fighting in the hitherto peaceful city of Kabul. Hassan is a successful "kite runner" for Amir; he knows where the kite will land without watching it. Amir's father, a wealthy merchant Amir affectionately refers to as Baba, loves both boys, but is often critical of Amir, considering him weak and lacking in courage. Amir finds a kinder fatherly figure in Rahim Khan, Baba's closest friend, who understands him and supports his interest in writing.

Assef, an older boy with a sadistic taste for violence, mocks Amir for socializing with a Hazara, which is, according to Assef, an inferior race whose members belong only in Hazarajat. One day, he prepares to attack Amir with brass knuckles, but Hassan defends Amir, threatening to shoot out Assef's eye with his slingshot. Assef backs off but swears to get revenge.

One triumphant day, Amir wins the local kite fighting tournament and finally earns Baba's praise. Hassan runs for the last cut kite, a great trophy, saying to Amir, "For you, a thousand times over." However, after finding the kite, Hassan encounters Assef in an alleyway. Hassan refuses to give up the kite, and Assef beats him severely and rapes him. Amir witnesses the act but is too scared to intervene. He knows that if he fails to bring home the kite, Baba would be less proud of him. He feels incredibly guilty but knows his cowardice would destroy any hopes for Baba's affections, so he keeps quiet about the incident. Afterwards, Amir keeps distant from Hassan; his feelings of guilt prevent him from interacting with the boy.

Amir begins to believe that life would be easier if Hassan were not around, so he plants a watch and some money under Hassan's mattress in hopes that Baba will make him leave; Hassan falsely confesses when confronted by Baba. Although Baba believes "there is no act more wretched than stealing", he forgives him. To Baba's sorrow, Hassan and Ali leave anyway. Amir is freed of the daily reminder of his cowardice and betrayal, but he still lives in their shadow.

Part II

In 1979, five years later, the Soviet Union militarily intervenes in Afghanistan. Amir and Baba escape to Peshawar, Pakistan, and then to Fremont, California, where they settle in a run-down apartment. Baba begins work at a gas station. After graduating from high school, Amir takes classes at San Jose State University to develop his writing skills. Every Sunday, Baba and Amir make extra money selling used goods at a flea market in San Jose. There, Amir meets fellow refugee Soraya Taheri and her family. Baba is diagnosed with terminal cancer but is still capable of granting Amir one last favor: he asks Soraya's father's permission for Amir to marry her. He agrees and the two marry. Shortly thereafter Baba dies. Amir and Soraya settle down in a happy marriage, but to their sorrow they learn that they cannot have children.

Amir embarks on a successful career as a novelist. Fifteen years after his wedding, Amir receives a call from his father's best friend (and his childhood father figure) Rahim Khan, who is dying, asking him to come see him in Peshawar. He enigmatically tells Amir, "There is a way to be good again." Now enticed, Amir goes.

Part III

From Rahim Khan, Amir learns that Ali was killed by a land mine and that Hassan and his wife were killed after Hassan refused to allow the Taliban to confiscate Baba and Amir's house in Kabul. Rahim Khan further reveals that Ali, being sterile, was not Hassan's biological father. Hassan was actually Baba's son and Amir's half-brother. Finally, he tells Amir that the reason he called Amir to Pakistan was to rescue Sohrab, Hassan's son, from an orphanage in Kabul.

Amir, accompanied by Farid, an Afghan taxi driver and veteran of the war with the Soviets, searches for Sohrab. They learn that a Taliban official comes to the orphanage often, brings cash, and usually takes a girl away with him. Occasionally he chooses a boy, recently Sohrab. The director tells Amir how to find the official, and Farid secures an appointment at his home by claiming to have "personal business" with him.

Amir meets the man, who reveals himself as Assef. Sohrab is being kept at Assef's house. Assef agrees to relinquish him if Amir can beat him in a fight. Assef then badly beats Amir, breaking several bones, until Sohrab uses a slingshot to fire a brass ball into Assef's left eye. Sohrab helps Amir out of the house, where he passes out and wakes up in a hospital.

Amir tells Sohrab of his plans to take him back to America and possibly adopt him. However, American authorities demand evidence of Sohrab's orphan status. Amir tells Sohrab that he may have to go back to the orphanage for a little while as they encounter a problem in the adoption process, and Sohrab, terrified about returning to the orphanage, attempts suicide. Amir eventually manages to take him back to the United States. After his adoption, Sohrab refuses to interact with Amir or Soraya until the former reminisces about Hassan and kites and shows off some of Hassan's tricks. In the end, Sohrab only gives a lopsided smile, but Amir takes it with all his heart as he runs the kite for Sohrab, saying, "For you, a thousand times over."

Characters

- Amir is the narrator of the novel. Khaled Hosseini acknowledged that the character is "an unlikable coward who failed to come to the aid of his best friend" for much of the duration of the story; consequently, Hosseini chose to create sympathy for Amir through circumstances rather than the personality he was given until the last third of the book.[17] Born into a Pashtun family in 1963, his mother died giving birth. As a child, he enjoys storytelling and is encouraged by Rahim Khan to become an author. At age 18, he and his father flee to America following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, where he pursues his dream of being a writer.

- Hassan is Amir's closest childhood friend. He is described as having a China doll face, green eyes, and a harelip. Hosseini regards him as a flat character in terms of development; he is "a lovely guy and you root for him and you love him but he's not complicated".[16] The reader eventually discovers that Hassan is actually the son of Baba and Sanaubar, although Hassan never discovers this during his lifetime. Moreover, it would make Hassan a Pashtun according to tribal law and not Hazara as he's actually the son of Baba, and ironic for Assef to bully him as both Assef and Hassan are half Pashtuns. Hassan is later killed by the Taliban for refusal to abandon Amir's property.

- Assef is the son of a Pashtun father and a German mother, and believes that Pashtuns are superior to Hazaras, despite himself not being full Pashtun. As a teenager, he is a neighborhood bully and is described as a "sociopath" by Amir. He rapes Hassan as a means of getting revenge against Amir. As an adult, he joins the Taliban and sexually abuses Hassan's son, Sohrab.

- Baba is Amir's father and a wealthy businessman who aids the community by creating businesses for others and building a new orphanage. He is the biological father of Hassan, a fact he hides from both of his children, and seems to favor him over Amir. Similar to Hosseini's father,[11] Baba does not endorse the religiosity demanded by the clerics in the religion classes attended by Amir in school. In his later years, after fleeing to America, he works at a gas station. He dies from cancer in 1987, shortly after Amir and Soraya's wedding.

- Ali is Baba's servant, a Hazara believed to be Hassan's father. In his youth, Baba's father adopted him after his parents were killed by a drunk driver. Before the events of the novel, Ali had been struck with polio, rendering his right leg useless. Because of this, Ali is constantly tormented by children in the town. He is later killed by a land mine in Hazarajat.

- Rahim Khan is Baba's loyal friend and business partner, as well as a mentor to Amir. Rahim persuades Amir to come to Pakistan to inform him that Hassan is his half brother and that he should rescue Sohrab.

- Soraya is a young Afghan woman whom Amir meets and marries in America. Hosseini originally scripted the character as an American woman, but he later agreed to rewrite her as an Afghan immigrant after his editor did not find her background believable for her role in the story.[18] The change contributed towards an extensive revision of Part III.[18] In the final draft, Soraya lives with her parents, Afghan general Taheri and his wife, and wants to become an English teacher. Before meeting Amir, she ran away with an Afghan boyfriend in Virginia, which, according to Afghan tradition, made her unsuitable for marriage. Because Amir also had his own regrets, he loves and marries her anyway.

- Sohrab is the son of Hassan. After his parents are killed and he is sent to an orphanage, Assef buys and abuses the child. Amir saves and later adopts him. After being brought to the United States, he slowly adapts to his new life. Sohrab greatly resembles a young version of his father Hassan.

- Sanaubar is Ali's wife and the mother of Hassan. Shortly after Hassan's birth, she runs away from home and joins a group of traveling dancers. She later returns to Hassan in his adulthood. To make up for her neglect, she provides a grandmother figure for Sohrab, Hassan's son.

- Farid is a taxi driver who is initially abrasive toward Amir, but later befriends him. Two of Farid's seven children were killed by a land mine, a disaster which mutilated three fingers on his left hand and also took some of his toes. After spending a night with Farid's brother's impoverished family, Amir hides a bundle of money under the mattress to help them.

Themes

Because its themes of friendship, betrayal, guilt, redemption and the uneasy love between fathers and sons are universal themes, and not specifically Afghan, the book has been able to reach across cultural, racial, religious and gender gaps to resonate with readers of varying backgrounds.— Khaled Hosseini, 2005[3]

Khaled Hosseini identifies a number of themes that appear in The Kite Runner, but reviewers have focused on guilt and redemption.[9][11][19] As a child, Amir fails to save Hassan in an act of cowardice and afterwards suffers from an all-consuming guilt. Even after leaving the country, moving to America, marrying, and becoming a successful writer, he is unable to forget the incident. Hassan is "the all-sacrificing Christ-figure, the one who, even in death, calls Amir to redemption".[19] Following Hassan's death at the hands of the Taliban, Amir begins to redeem himself through the rescue of Hassan's son, Sohrab.[20] Hosseini draws parallels during the search for Sohrab to create an impression of poetic justice; for example, Amir sustains a split lip after being severely beaten, similar to Hassan's harelip.[20] Despite this, some critics questioned whether the protagonist had fully redeemed himself.[21]

Amir's motivation for the childhood betrayal is rooted in his insecurities regarding his relationship with his father.[22] The relationship between parents and their children features prominently in the novel, and in an interview, Hosseini elaborated:

Both [The Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns] are multigenerational, and so the relationship between parent and child, with all of its manifest complexities and contradictions, is a prominent theme. I did not intend this, but I am keenly interested, it appears, in the way parents and children love, disappoint, and in the end honor each other. In one way, the two novels are corollaries: The Kite Runner was a father-son story, and A Thousand Splendid Suns can be seen as a mother-daughter story.[2]

When adapting The Kite Runner for the theatre, Director Eric Rose stated that he was drawn into the narrative by the "themes of betraying your best friend for the love of your father", which he compared to Shakespearean literature.[23] Throughout the story, Amir craves his father's affection;[22] his father, in turn, loves Amir but favors Hassan,[20] going as far as to pay for plastic surgery to repair the latter's cleft lip.[24]

Critical reception

General

In the first two years following its publication, over 70,000 hardback copies of The Kite Runner were sold along with 1,250,000 paperback copies.[3] Though the book sold well in hardback, "Kite Runner's popularity didn't really begin to soar until [2004] when the paperback edition came out, which is when book clubs began picking it up."[9] It started appearing on best seller lists in September 2004 and became a number one New York Times best seller in March 2005,[3] maintaining its place on the list for two years.[4] By the publication of Khaled Hosseini's third novel in 2013, over seven million copies had been sold in the United States.[5] The book received the South African Boeke Prize in 2004. It was voted the Reading Group Book of the Year for 2006 and 2007 and headed a list of 60 titles submitted by entrants to the Penguin/Orange Reading Group prize (UK).[26][27]

Critically, the book was well-received, albeit controversial. Erika Milvy from Salon praised it as "beautifully written, startling and heart wrenching".[28] Tony Sims from Wired Magazine wrote that the book "reveals the beauty and agony of a tormented nation as it tells the story of an improbable friendship between two boys from opposite ends of society, and of the troubled but enduring relationship between a father and a son".[29] Amelia Hill of The Guardian opinionated, "The Kite Runner is the shattering first novel by Khaled Hosseini" that "is simultaneously devastating and inspiring."[22] A similarly favorable review was printed in Publishers Weekly.[13] Marketing director Melissa Mytinger remarked, "It's simply an excellent story. Much of it based in a world we don't know, a world we're barely beginning to know. Well-written, published at the 'right time' by an author who is both charming and thoughtful in his personal appearances for the book."[3] Indian-American actor Aasif Mandvi agreed that the book was "amazing storytelling. ... It's about human beings. It's about redemption, and redemption is a powerful theme."[9] First Lady Laura Bush commended the story as "really great".[25] Said Tayeb Jawad, the 19th Afghan ambassador to the United States, publicly endorsed The Kite Runner, saying that the book would help the American public to better understand Afghan society and culture.[9]

Edward Hower from The New York Times analyzed the portrayal of Afghanistan before and after the Taliban:

Hosseini's depiction of pre-revolutionary Afghanistan is rich in warmth and humor but also tense with the friction between the nation's different ethnic groups. Amir's father, or Baba, personifies all that is reckless, courageous and arrogant in his dominant Pashtun tribe ... The novel's canvas turns dark when Hosseini describes the suffering of his country under the tyranny of the Taliban, whom Amir encounters when he finally returns home, hoping to help Hassan and his family. The final third of the book is full of haunting images: a man, desperate to feed his children, trying to sell his artificial leg in the market; an adulterous couple stoned to death in a stadium during the halftime of a football match; a rouged young boy forced into prostitution, dancing the sort of steps once performed by an organ grinder's monkey.[24]

Meghan O'Rouke, Slate Magazine's culture critic and advisory editor, ultimately found The Kite Runner mediocre, writing, "This is a novel simultaneously striving to deliver a large-scale informative portrait and to stage a small-scale redemptive drama, but its therapeutic allegory of recovery can only undermine its realist ambitions. People experience their lives against the backdrop of their culture, and while Hosseini wisely steers clear of merely exoticizing Afghanistan as a monolithically foreign place, he does so much work to make his novel emotionally accessible to the American reader that there is almost no room, in the end, for us to consider for long what might differentiate Afghans and Americans."[25] Sarah Smith from The Guardian thought the novel started out well but began to falter towards the end. She felt that Hosseini was too focused on fully redeeming the protagonist in Part III and in doing so created too many unrealistic coincidences that allowed Amir the opportunity to undo his past wrongs.[20]

Controversies

The Kite Runner has been accused of 'hindering' Western understanding of the Talibans by portraying its members as representatives of various social and doctrinal evils that the Talibans and their supporters do not consider typical and which they feel portray Talibans in an unfavourable light. Examples of this would be: Assef's pedophilia, Nazism, drug abuse, and sadism, and the fact that he is an executioner.[30] The American Library Association reported that The Kite Runner was one of its most-challenged books of 2008, with multiple attempts to remove it from libraries due to "offensive language, sexually explicit, and unsuited to age group."[31] Afghan American readers were particularly hostile towards the depiction of Pashtuns as oppressors and Hazaras as the oppressed.[11] Hosseini responded in an interview, "They never say I am speaking about things that are untrue. Their beef is, 'Why do you have to talk about these things and embarrass us? Don't you love your country?'"[11]

The film generated more controversy through the 30-second rape scene, with threats made against the child actors, who originated from Afghanistan.[28] Zakria Ebrahimi, the 12-year-old actor who portrayed Amir, had to be removed from school after his Hazara classmates threatened to kill him,[32] and Paramount Pictures was eventually forced to relocate three of the children to the United Arab Emirates.[28] Afghanistan's Ministry of Culture banned the film from distribution in cinemas or DVD stores, citing the possibility that the movie's ethnically charged rape scene could incite racial violence within Afghanistan.[33]

Adaptations

Film

.jpg)

Four years after its publication, The Kite Runner was adapted as a motion picture starring Khalid Abdalla as Amir, Homayoun Ershadi as Baba, and Ahmad Khan Mahmoodzada as Hassan. It was initially scheduled to premiere in November 2007, but the release date was pushed back six weeks to evacuate the Afghan child stars from the country after they received death threats.[34] Directed by Marc Forster and with a screenplay by David Benioff, the movie won numerous awards and was nominated for an Academy Award, the BAFTA Film Award, and the Critics Choice Award in 2008.[35] While reviews were generally positive, with Entertainment Weekly deeming the final product "pretty good",[36] the depiction of ethnic tensions and the controversial rape scene drew outrage in Afghanistan.[34] Hangama Anwari, the child rights commissioner for the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, commented, "They should not play around with the lives and security of people. The Hazara people will take it as an insult."[34]

Hosseini was surprised by the extent of the controversy caused by the rape scene and vocalized that Afghan actors would not have been cast had studios known that their lives would be threatened.[28] He believed that the scene was necessary to "maintain the integrity" of the story, as a physical assault by itself would not have affected the audience as much.[28]

Other

The novel was first adapted to the stage in March 2007 by Bay Area playwright Matthew Spangler where it was performed at San Jose State University.[37] Two years later, David Ira Goldstein, artistic director of Arizona Theater Company, organized for it to be performed at San Jose Repertory Theatre. The play was produced at Arizona Theatre Company in 2009, Actor's Theatre of Louisville and Cleveland Play House in 2010, and The New Repertory Theatre of Watertown, Massachusetts in 2012. The theatre adaption premiered in Canada as a co-production between Theatre Calgary and the Citadel Theatre in January 2013. In April 2013, the play premiered in Europe at the Nottingham Playhouse, with Ben Turner acting in the lead role.[38]

Hosseini was approached by Piemme, his Italian publisher, about converting The Kite Runner to a graphic novel in 2011. Having been "a fan of comic books since childhood", he was open to the idea, believing that The Kite Runner was a good candidate to be presented in a visual format.[29] Fabio Celoni provided the illustrations for the project and regularly updated Hosseini on his progress before its release in September of that year.[29] The latter was pleased with the final product and said, "I believe Fabio Celoni's work vividly brings to life not only the mountains, the bazaars, the city of Kabul and its kite-dotted skies, but also the many struggles, conflicts, and emotional highs and lows of Amir's journey."[29]

See also

- 16 Days in Afghanistan

- A Thousand Splendid Suns (Hosseini's second novel)

References

- ↑ Noor, R.; Hosseini, Khaled (September–December 2004). "The Kite Runner". World Literature Today. 78 (3/4): 148. doi:10.2307/40158636.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "An interview with Khaled Hosseini". Book Browse. 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Guthmann, Edward (March 14, 2005). "Before 'The Kite Runner,' Khaled Hosseini had never written a novel. But with word of mouth, book sales have taken off". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- 1 2 Italie, Hillel (October 29, 2012). "'Kite Runner' author to debut new novel next year". NBC News. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- 1 2 "Siblings' Separation Haunts In 'Kite Runner' Author's Latest". NPR. May 19, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- ↑ Jain, Saudamini (May 24, 2013). "COVER STORY: the Afghan story teller Khaled Hosseini". Hindustan Times. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Miller, David (June 7, 2013). "Khaled Hosseni author of Kite Runner talks about his mistress: Writing". Loveland Magazine. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "'Kite Runner' Author On His Childhood, His Writing, And The Plight Of Afghan Refugees". Radio Free Europe. June 21, 2012. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Wilson, Craig (April 18, 2005). "'Kite Runner' catches the wind". USA Today. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ↑ Grossman, Lev (May 17, 2007). "The Kite Runner Author Returns Home". Time Magazine. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Young, Lucie (May 19, 2007). "Despair in Kabul". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ Mehta, Monica (June 6, 2003). "The Kite Runner". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- 1 2 "The Kite Runner". Publishers Weekly. May 12, 2003. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ↑ Tonkin, Boyd (February 28, 2008). "Is the Arab world ready for a literary revolution?". The Independent. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ↑ Deutsch, Lindsay (February 28, 2013). "Book Buzz: 'Kite Runner' celebrates 10th anniversary". USA Today. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- 1 2 Hoby, Hermione (May 31, 2013). "Khaled Hosseini: 'If I could go back now, I'd take The Kite Runner apart'". The Guardian. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ↑ Kakutani, Michiko (May 29, 2007). "A Woman's Lot in Kabul, Lower Than a House Cat's". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- 1 2 Wyatt, Edward (December 15, 2004). "Wrenching Tale by an Afghan Immigrant Strikes a Chord". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- 1 2 Rankin-Brown, Maria (January 7, 2008). "The Kite Runner: Is Redemption Truly Free?". Spectrum Magazine. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, Sarah (October 3, 2003). "From harelip to split lip". The Guardian. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ↑ Thompson, Harvey (March 25, 2008). "The Kite Runner: the Afghan tragedy goes unexplained". WSWS. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Hill, Amelia (September 6, 2003). "An Afghan hounded by his past". The Guardian. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ Roe, John (February 4, 2013). "The Kite Runner". Calgary Herald. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- 1 2 Hower, Edward (August 3, 2003). "The Servant". The New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- 1 2 3 O'Rourke, Meghan (July 25, 2005). "Do I really have to read 'The Kite Runner'?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ↑ Lea, Richard (7 August 2006). "Word-of-mouth success gets reading group vote". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ↑ Pauli, Michelle (August 15, 2007). "Kite Runner is reading group favourite for second year running". guardian.co.uk. London. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Milvy, Erika (December 9, 2007). "The "Kite Runner" controversy". Salon. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Sims, Tony (September 30, 2011). "GeekDad Interview: Khaled Hosseini, Author of The Kite Runner". Wired. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ Sengupta, Kim (October 24, 2008). "Butcher and Bolt, By David Loyn". The Independent Books. London. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- ↑ "Top ten most frequently challenged books of 2008, by ALA Office of Intellectual Freedom". ALA Issues and Advocacy. Archived from the original on 19 October 2009. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ↑ Soraya Sarhaddi Nelson (July 2, 2008). "'Kite Runner' Star's Family Feels Exploited By Studio". All Things Considered. National Public Radio.

- ↑ "'The Kite Runner' Film Outlawed in Afghanistan". The New York Times. January 16, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Halbfinger, David (October 4, 2007). "'The Kite Runner' Is Delayed to Protect Child Stars". The New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Hollywood Foreign Press Association 2008 Golden Globe Awards". goldenglobes.org. December 13, 2007. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ↑ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (January 9, 2008). "The Kite Runner". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ↑ "'Kite Runner' floats across SJSU stage on Friday night". Spartan Daily. February 22, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Review: The Kite Runner/Liverpool Playhouse". Liverpool Confidential. June 25, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Kite Runner |

- Official website of author Khaled Hosseini

- Khaled Hosseini discusses The Kite Runner on the BBC World Book Club

- Article on the novel at Let's Talk about Bollywood

- Excerpts: Excerpt at ereader.com Excerpt at litstudies.org Excerpt at today.com

- Book Drum illustrated profile of The Kite Runner