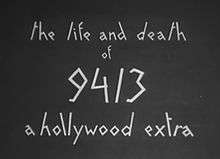

The Life and Death of 9413: a Hollywood Extra

| The Life and Death of 9413: a Hollywood Extra | |

|---|---|

The title card from The Life and Death of 9413: a Hollywood Extra | |

| Directed by | |

| Produced by | Robert Florey |

| Written by |

|

| Starring |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 11 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

Silent English intertitles |

| Budget | $97 |

The Life and Death of 9413: a Hollywood Extra is a 1928 American silent experimental short film co-written and co-directed by Robert Florey and Slavko Vorkapić. Considered a landmark of American avant-garde cinema, it tells the story of a man (Jules Raucourt) who comes to Hollywood with dreams of becoming a star, only to fail and become dehumanized, with studio executives reducing him to the role of extra and writing the number "9413" on his forehead.

The film's visual style includes abrupt cuts, rapid camera movement, extensive superimposition, dim lighting, and shapes and forms in twisted and disoriented angles. Filmed with a budget of only $97 ($1,339 in today's dollars), it includes a combination of close-ups of live actors and long shots of miniature sets, which were made from such items as cardboard, paper cubes, tin cans, cigar boxes, and toy trains. With no access to Hollywood studios or equipment, most of the filming took place in the filmmakers' residences, with walls painted black for use as a background.

The story was inspired by Florey's own experiences in Hollywood, as well as the George Gershwin composition Rhapsody in Blue. It was one of the first films shot by Gregg Toland, who later received acclaim for his work on such films as The Grapes of Wrath (1939) and Citizen Kane (1941). The film serves as a satire of the social conditions, dominant practices, and ideologies of Hollywood, as well as the film industry's perceived mistreatment of actors. Douglas Fairbanks assisted with the development of the film, and Charlie Chaplin and Joseph M. Schenck helped promote it.

Unlike most experimental films, it received a wide public exhibition, released by FBO Pictures Corporation into more than 700 theaters in North America and Europe. The film was well received by critics, both in its time period and in modern day; film historian Brian Taves said "more than any other American film, it initiated the avant-garde in this country". The entirety of the film has not survived. It has been selected for preservation by the National Film Registry, and Florey co-wrote and directed a remake, Hollywood Boulevard (1936).

Plot

Mr. Jones (Jules Raucourt), an artist and aspiring movie star, arrives in Hollywood and is immediately star-struck by the glitz and glamour of the film industry. He speaks with a film studio representative, presenting a letter of recommendation and attempting to speak on his own behalf, but the representative cuts him off and writes the number "9413" on his forehead. From this point on, 9413 speaks only in unintelligible gibberish and moves in a mechanical fashion, mindlessly following the instructions of film directors and studio representatives. He goes on a series of casting calls, but is unable to find any success, constantly being confronted with signs that read, "No Casting Today". A series of images are interspersed throughout these scenes, including shots of Hollywood, cameras filming, the word "DREAMS" written in the stars, and an endlessly repeating loop of a man walking up a stairway toward the word "SUCCESS", without ever reaching the top.

Unlike 9413, other extras around him begin to find success. A woman (Adriane Marsh) with the number "13" on her head constantly kneels and stands back up at the behest of a film director, and eventually succeeds in landing a part, greeted by a "Casting Today" sign. Another extra (Voya George) with the number "15", who unlike 9413 has expressionless and unenthusiastic facial expressions, holds paper masks in front of his face, symbolizing his performances. He is greeted with enthusiasm by the cheering masses, all of whom speak in the same gibberish as 9413. His number 15 is replaced with a star and he achieves tremendous success. 9413 admires this new movie star and attempts to mimic him, presenting his own, much more impressive-looking mask. But the star is unimpressed and disregards 9413, who sadly cradles his mask like a baby, lamenting his inability to achieve success.

Time passes and 9413 remains unable to find work in Hollywood. Despite constant phone calls to studio representatives begging for work, he is repeatedly confronted by "No Casting Today" signs. He cannot afford to buy food, and bills that he is unable to pay are constantly slipped under his door. A series of images symbolizing his mental anguish are shown, including twisted trees blowing in the wind, and a man laying on the stairway leading to "SUCCESS", still unable to reach the top. He falls to the ground, starving, exhausted, and in a state of despair over his failures. Finally, he dies, and after images are shown of the other actors laughing at him, his tombstone is revealed to read "Here Lies No. 9413, a Hollywood Extra", next to the words "No Casting Today".

After his death, 9413's spirit leaves his body and is pulled by a platform into the sky. As he gets higher, he grows angel wings and ascends into heaven, a place with glittering crystal towers and bright blinking lights. A hand removes the "9413" from his forehead, and he smiles happily before flying further into heaven.

Production

Conception

Robert Florey and Slavko Vorkapić, who met after Florey attended one of Vorkapić's American Society of Cinematographers lectures,[1] are credited as co-writers and co-directors of The Life and Death of 9413: a Hollywood Extra.[2] Accounts differ as to the level of involvement the two men had in the creation of the film, but most identify Florey as primarily responsible.[3] Film historian Brian Taves has claimed Vorkapić was not involved in the writing or direction of the film, and that his contribution was limited to set design and miniature lighting, but that Florey nevertheless insisted on sharing equal credit with him for his role in bringing the film to fruition.[3][4] Some early journalistic stories about the film uphold this viewpoint, including a 1928 article about Florey in Hollywood Magazine.[3] Taves further claims that while Vorkapić did nothing to promote the film when it was first released, he later exaggerated his role in the production of the film when it became so esteemed.[3][5] Paul Ivano, who did camerawork on the film, echoed these sentiments, saying: "Vorkapić tries to get credit, but he didn't do much."[6] For his part, Vorkapić himself has said the initial idea was Florey's, and that they discussed it and drafted a rough one-page synopsis together. But Vorkapić said "all the effects were devised, designed, photographed, and added by me", and that "at least 90 percent of the editing and montage" was his work.[1] He claims to have directed most of the opening and ending sequences himself, while he credits Florey with filming the casting scene and shots of laughing extras, and said the rise of Voya George's character to stardom was filmed jointly.[1]

Within a few years of his first arrival in Hollywood, Florey conceived the idea of making a film about the common actor's dreams of becoming a star, and subsequent failure to achieve his hopes.[7] Florey's work as a publicist and journalist covering the film industry gave him familiarity with the struggles of aspiring actors and their disappointment at failing to achieve their dreams, which informed the writing of A Hollywood Extra.[8] But the final inspiration for the film came after Florey attended a performance of the George Gershwin composition Rhapsody in Blue.[8][9][10] Florey had been working in Hollywood for only a few months when he heard the music, and it inspired him to incorporate the rhythm of the blues into a film.[10] He would later describe the film as a "continuity in musical rhythm of the adventures of my extra in Hollywood, the movements and attitudes of which appeared to synchronize themselves with Gershwin's notes".[8] Although most avant-garde films of the time emphasized moods rather than emotion, he wanted his script to merge both abstraction and narrative in equal parts.[11] Florey wrote the script in precise detail, describing each shot in proportion to the length of film it would take to shoot it, which was necessary due to the high cost of film stock.[8]

Development

Florey owned no camera at the time, and his efforts to obtain one were unsuccessful until he met Vorkapić.[10][12] Florey said of their discussion: "I say to Slav, 'Slav, I have an idea but not much money. You have a camera and are a clever painter. Let's make the picture in collaboration and we split the benefit.'"[12] Vorkapić himself claimed to have said: "Florey, you get me 100 dollars and I'll make you a picture in my own kitchen."[1] Vorkapić allowed Florey to borrow a small box camera that he had purchased with the proceeds from the sale of one of his oil paintings.[10][13] It was a DeVry camera with one lens, a type that Florey said was sold as a "toy".[12] Florey also had trouble obtaining film, as he found it cost-prohibitive to purchase negative and positive film from film laboratories.[10] However, Florey knew that "film ends", scraps of leftover unexposed film stock, were often discarded after shooting on big budget Hollywood films, so he attempted to persuade filmmakers to give them to him.[9][10] Camera work had just been completed on The Gaucho, a film starring Douglas Fairbanks, and he was able to obtain more than 1,000 feet of film from the production in 10- and 20-foot strips.[10] Florey then spliced the film ends together by hand, a process he found time-consuming and frustrating, but one that resulted in the equivalent of a full reel of negative film.[10] Fairbanks, who had previously hired Florey to handle his European public relations, provided financial assistance for the production of A Hollywood Extra.[9] He also gave Florey access to his editing rooms and helped provide him with film ends.[9][14]

The film was shot by Gregg Toland, credited simply as "Gregg",[15] who was simultaneously working as an assistant to cinematographer George Barnes at the Samuel Goldwyn Studio.[9] It was one of the first films for Toland,[16] who later received acclaim for his cinematography on such films as The Grapes of Wrath (1939) and Citizen Kane (1941).[13][17][18] The Life and Death of 9413: a Hollywood Extra cost $97 ($1,339 today) to make,[9][19][20] which was covered entirely by Florey.[21] The budget was composed of $55 ($759 today) for development and printing, $25 ($345 today) for negatives, $14 ($193 today) for transportation, and $3 ($41 today) for store props, most of which cost five or ten cents individually.[22] From the development costs, the salary expenses for everyone involved in the film totaled $3.[1] Toland had use of a Mitchell camera during filming, which allowed for some shots that would have been impossible with the DeVry carema, including about 300 feet of closeups.[23] Additional camerawork was done by Paul Ivano,[24] and Taves has in fact argued that Ivano was primarily responsible for much of the film's camerawork, with Toland handling primarily the close-ups.[3] The film was shot on 35 mm film,[2] over a period of three weeks in late 1927,[12] filmed mostly on weekends.[2] No subtitles are used in the film. Only two captions are used, each with one word – "DREAMS" and "SUCCESS" – but they are created not through subtitles, but by reflecting moving light through cardboard cutouts, creating words among the shadows.[24]

Casting

The role of extra 9413 was played by Jules Raucourt, credited in the film simply as "Raucourt". Although Raucourt started his career as a leading man of silent action films, he ironically became a film extra himself after cinema transitioned into the sound era.[25][26][27] Raucourt later wrote a novel using the title of the film.[6] The role of Extra #13 was played by Adriane Marsh, herself a film extra,[25][26] who never again obtained a named role in cinema.[26] Extra #15, who then becomes a movie star, was portrayed by Voya George, a personal friend of Vorkapić,[25][26] who went on to a career in European films.[1] Robert Florey also himself appears in the film as a casting director,[6][13] although only his disembodied mouth and hand are visible, shaking his finger at the protagonist.[6] Slavko Vorkapić also had a brief role in the film as the man constantly walking up the stairs toward the words "SUCCESS".[1]

Filming

The filmmakers had no access to a studio,[20] so shooting took place in rooms at their homes, with the walls painted black for use as a background.[20] Herman G. Weinberg, a writer for Movie Makers, and Jack Spears of Films in Review, said it was filmed mostly at Florey's residence,[20][28] while film historian David E. James claimed it was filmed in Vorkapić's kitchen.[2] In an interview, Florey claimed the filming took place both in his kitchen and in Vorkapić's living room.[1] Some scenes were also filmed in Toland's garage.[28][29] The film is shot in three basic types of compositions: miniature sets, close-ups of live actors, and newsreel-like scenes of Hollywood and film studios. The film's visual motif includes abrupt cuts, rapid camera movement, extensive superimposition, dim lighting, and shapes and forms in twisted and disoriented angles. In this way, it shares some similarities with German Expressionism,[24][30][31] particularly the film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).[31][32] The opening credits, in particular, are angular and expressionistic.[2] A single 400-watt lamp was used as lighting in the film;[19][24] they originally planned to use two lamps, but one of them burned out before filming began.[1] During close-up shots, the actors would hold the light bulb in their hands so their faces would be lit. When an actor changed position, he or she would switch the bulb from one hand to another.[20][23] As a result, the faces of the actors are often kept in partial shadow, keeping their features obscured.[24] Toland also used small reflectors that he borrowed from film studios, which included a light bulb hung inside a mirror shaped like a cone.[1] The film's acting is heavily abstract and stylized, with the actors mouthing gibberish instead of speaking actual words.[13][31] A record of Rhapsody in Blue was played constantly during filming, so that the actors would, in Florey's words, become "saturated" with the rhythm of the "blues". This was a source of aggravation for Florey's neighbors and landlord.[6]

Scenes of Hollywood cityscapes, as well as shots of heaven at the end of the film, were achieved through the creation of miniature sets that were filmed in long shots to give the appearance that they were large and expansive.[33][34] A total of 45 sets were built in total, none larger than about two square feet, with the most expensive costing $1.67. It took days to prepare these sets. Florey cut cardboard from laundered shirts and shaped them into squares while Vorkapić painted them impressionistically to resemble buildings.[29] The elevated trains in the cityscape scenes were actually toy trains Florey purchased and mounted on pasteboard runaways. He would pull them along the track on a string with one hand while he shot the scene with the other.[33] Movement on the miniature sets was simulated by moving lamps and casting shadows.[34] To make the miniature sets look more realistic and to conceal defects, prisms and kaleidoscopes were placed in front of the camera lens and moved during filming, and cylinder lens systems were used and rotated during shooting to magnify the image to the desired diameter. Florey said this was useful in "giving the scenes the rhythms which we thought they required".[35]

Skyscrapers in the sets were oblong cubes that were shot from an angle that exaggerated their height. To create the effect of sunlight glimmering off the buildings, one person would stand on one side of the cubes with a mirror, and another would stand on the opposite side with a light bulb and swing it back and forth, so the mirror could catch reflections of the swinging light and throw it back onto the skyscrapers.[33] To create a sense of hysteria and excitement surrounding an opening night performance, a skyscraper was photographed with the camera swinging quickly up and down from side to side.[33] While scenes from miniature sets were composed of long shots, scenes were actors were shot entirely in close-ups,[34] which make up about 300 feet of the final film reel.[29] Rather than attempting to put the actor into the miniature backgrounds through trick photography, the scenes were cut rapidly and successively, so the viewer first sees the actor and then the set, creating the impression they are in the same place.[34] Sets involving actors were minimalistic, with some consisting of only a few elements like a table, telephone, two chairs, and a cigar.[9]

A film studio set was created by photographing several reel spools with strips of film dangling against a background of blinking lights. The casting office was created by silhouetting strips of cardboard against a white background.[33] To portray the mental anguish of the protagonist, strips of paper were cut into the shape of twisted trees, which were silhouetted against a background of moving shadows and set in motion with an electric fan.[33] To create a scene near the end of the film, when the protagonist starts becoming delirious, the camera moves through a maze of different sized cubes, with geometric designs inside them, all placed on a flat, shiny service.[33] The heaven setting was also a miniature set created from paper cubes, tin cans, cigar boxes, toy trains, and a motorized Erector Set.[28][33][36] No still photos were taken for the film, but illustrations showing prism and kaleidoscope effects have been made by enlarging frames of negative. The paper prints were considerably softer than the movie print in order to avoid graininess.[35] The final film was edited to a one-reel length of 1,200 feet of film strip,[2][23] featuring about 150 scenes.[6] Florey said it featured the same number of angles as full-length feature films of the time.[1] Although the film was carefully edited to be synchronized with Rhapsody in Blue, much of the original lyrical quality has been lost in shortened and modified versions of the film.[23][28]

Themes and interpretations

The film serves as a satire of the social conditions, dominant practices, and ideologies of Hollywood, as well as the film industry's perceived mistreatment of actors.[2][37] Filmmaking was becoming more expensive and requiring larger technical resources, particularly with the rise of sound production, making it increasingly difficult for amateur filmmakers to enter the profession. This deepened a divide between amateurs and Hollywood professionals, and as a result, a growing number of amateurs started lampooning Hollywood in their films, including A Hollywood Extra.[37] The subject of the film is an extra who starts his Hollywood career with hopes and dreams, but ultimately finds himself used and discarded by the industry, and his artistic ambitions destroyed.[10] At the start of the film, the protagonist has a name (Mr. Jones) and a letter of recommendation outlining his talents, but his abilities are ignored and he is reduced to a number, symbolizing his dehumanization.[2][38]

The movie star served as an illustration of hero worship in American culture, and the painted masks he dons represent his performances.[39] Actors and spectators alike are portrayed as unintelligent automatons, their mouths yapping senselessly as they respond to Hollywood films and to hand signals from film directors.[10][30] One scene repeatedly loops the same shot of a man climbing a flight of stairs with the word "SUCCESS" atop it, representing the actors' vain attempts to find fulfillment and advancement in his career. Film historians William Moritz and David E. James have compared this to a similar scene involving a washerwoman in the Dadaist post-Cubist film Ballet Mécanique (1924).[13][30] Other segments in the A Hollywood Extra are also frequently repeated, like views of the city lights, and shots of "Hollywood" and "No Casting" signs. This further exemplifies the protagonist's constant struggle to succeed in Hollywood.[40]

The film's abrupt cuts, artificial scenery, extreme close-ups, and twisted angles all metaphorically amplify the dark and somber narrative.[30] Shots of film producers and critics in A Hollywood Extra are shot from low angles with dark backdrops, giving the characters a powerful and foreboding ambiance. Gregg Toland would make use of similar camera techniques in his later work on Citizen Kane.[13] Due to the lighting, close-ups of the actors' faces are often shadowed, shrouding some of their features and depriving the characters of wholeness.[24] The all-black backdrops in these close-ups also derive the film of a real-world presence.[30] During a scene in which the protagonist await phone calls to learn about casting decisions, the image of a telephone is superimposed directly onto the actor's forehead, symbolizing his growing obsession with finding work.[13] His failure to achieve success mocks him even after his death, as the words "No Casting Today" appear next to his gravestone.[30] His death is symbolized by a pair of scissors cutting a film strip.[12][30]

While the film portrays the reality of the protagonist's experience in an expressionistic style, the glamour of Hollywood is portrayed more objectively. In reversing these conventional expectations, however, the film invites the viewer to interpret this version of Hollywood as merely "the material of dreams" and "an unreal paradise of cruelty and failure", according to Taves.[41] Scenes on the streets of Hollywood are filmed with a wildly moving camera from tilted angles, and edited into rapid juxtapositions, to reflect the false and excessive nature of the Hollywood film industry.[24] The protagonist's ascension to heaven at the end of the film serves simultaneously as a fitting conclusion to the story, and as a satire of Hollywood's desire for traditional happy endings.[12][28][42] As he ascends, heaven is located in the opposite direction from Hollywood, another jab at the industry.[12] James wrote that the vision of heaven as an escape from the film industry's brutality "figures the avant-garde's recurrent utopian aspirations".[43]

The film also touches upon Hollywood's perceived mistreatment of women. While the male actors wear masks, which symbolize their ability to act, the female Extra #13 does not wear any and is instead expected to simply stand obediently and listen to the male filmmakers. Her only role is to be an object for men to look upon.[36] The fact that she is able to achieve success by filling this simple role, contrasted against the protagonist's inability to succeed despite his hard work, reveals how differently the film industry views the roles of male and female actors.[36]

Release

Although most commonly known by its proper title, The Life and Death of 9413: a Hollywood Extra has also been released and advertised under different titles at various times, including Hollywood Extra 9413, and $97, a reference to the film's low budget.[44] Other titles include The Rhapsody of Hollywood,[14][45][46] a name suggested by comic actor and filmmaker Charlie Chaplin,[14][47] and The Suicide of a Hollywood Extra,[45] a misnomer created by the distributor, FBO Pictures Corporation.[47] While many experimental films from the period were simply screened in the filmmakers' homes for private audiences of families and friends, A Hollywood Extra received a wide public exhibition.[48] Upon its release, Florey described the film this way:[39]

| “ | It is not much. Just about a man who is a fine actor in Iowa or somewhere and who comes to Hollywood and expects to conquer it overnight. ... The would-be idol goes to the studios. ... The casting director, he is merely a hand that rejects or selects. ... And the rest just tells how he loses out all around. | ” |

Sources differ on when and where the film premiered. According to film critic Daniel Eagan, Florey premiered the film in a movie club in Los Angeles,[45] while film writer Anthony Slide wrote that it opened at New York City's Cameo Theatre on June 17, 1928.[39] However, David E. James said the film had its true premiere at Charlie Chaplin's villa in Beverly Hills, California.[18] Chaplin, who by this time was disenchanted with many aspects of Hollywood filmmaking,[45] was so impressed with the film that he watched it five times,[18][23] and then screened it for guests at his home. This audience included elites from the film industry,[18][23][45] including Douglas Fairbanks, John Considine, Harry d'Arrast, D. W. Griffith, Jesse L. Lasky, Ernst Lubitsch, Lewis Milestone, Mary Pickford, Joseph M. Schenck, Norma Talmadge, Josef von Sternberg, and King Vidor.[49][50] The screening was accompanied by a record of Rhapsody in Blue, as well as Chaplin himself playing the organ.[49] Florey was so fearful of a negative reaction due to the film's satire of Hollywood that he removed his name from the credits and hid in the projection room during the screening. While the audience originally expected it to be one of Chaplin's gags,[5][49] they were very impressed with the film,[23][45][49] and Schenck arranged for it to be shown on a United Artists Theater on Broadway starting on March 21, 1928.[18][28][51] A special musical score, based on Rhapsody in Blue, was prepared by Hugo Riesenfeld for the showing, which was played by a live orchestra,[49][51] and made heavy use of the saxophone.[49] With a presentation usually reserved for bigger budget films, it played twice nightly along with the Gloria Swanson film Sadie Thompson, and was billed as "the first of the impressionistic photoplays to be made in America".[51]

The film was heavily publicized,[52] which many of the media reports emphasizing its low budget of $97.[49] It achieved enough fame to become picked up for distribution by FBO Pictures Corporation,[31][45][51] which eventually became RKO Pictures through a merger.[45][51] The company released the film to more than 700 theaters in North America and Europe.[31][49] In North America, it was shown not only in New York and Hollywood, but also in the Philadelphia, Cleveland, Montreal, and Washington, D.C. areas.[51] It played in Philadelphia along with Prem Sanyas (1925), but it generated more praise than the main attraction film and earned $32 in a single week.[53] A Hollywood Extra became one of the first widely-seen American avant-garde films, not only in the United States but also throughout the Soviet Union and Europe,[43][54] including England, France, Germany, and Italy.[54] The French rights for the film, along with Florey's The Love of Zero (1928), were sold for $390.[53]

Though the film was made in opposition to classical style, it was embraced by those within the Hollywood industry,[43][55] and ultimately helped Florey, Vorkapić, and Toland get more prestigious assignments within the film industry.[18][55] Vorapich was offered a special effects position at Paramount Pictures shortly after A Hollywood Extra was released.[18] Paramount wanted to hire Florey for the position, but after Josef von Sternberg clarified that Vorkapić was most responsible for A Hollywood Extra's special effects, they made the offer to him.[49] Film production designer William Cameron Menzies was anxious to work with Florey after watching A Hollywood Extra, so the two co-authored The Love of Zero, with Florey directing and Menzies designing the sets.[4][56]

Reception

To the extent that The Life and Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra dramatizes the condition of human life enthralled by and ruined by the entertainment industry, the all-pervading, massively powerful imagery of capital itself, it is the prototypical 20th century avant-garde film.

David E. James, film historian[57]

The film was well received by critics, both in its time period and in modern day.[43][54] One reviewer said it ranked in cinema "where Gertrude Stein ranks in poetry",[43] while another praised Florey as "the Eugene O'Neill of the cinema".[5] A 1929 edition of Movie Makers, the official publication of the Amateur Cinema League, called it a triumph of amateur experimentation and imaginative use of limited resources.[37] In a separate Movie Makers article, Herman G. Weinberg called the scenery "a fantastically beautiful vision of a dream metropolis, done in the expressionistic manner, but done with a fine eye for the camera and the context of the piece".[33] C. Adolph Glassgold, contributing editor for the journal The Arts, called it "a truly tremendous picture" and said Florey could become "the eventual leader of cinematic art". He added: "It has movement, tempo, form, intensity of feeling, highly dramatic moments; in short, it is a real motion picture."[46] In a Film Mercury review, Anabel Lane predicted Florey would "one day hold a position of one of the bigger film directors", and said of the film: "If this production had been made in Europe and heralded as a hit, it would ... have been called a masterpiece."[5] One reviewer from Variety even speculated as to whether A Hollywood Extra was "an unannounced foreign-made short" given how similar in style it was to European art films.[43][54] Film director Henry King praised the film as "way ahead of its time" and "a stroke of genius", declaring: "It was the most original thought I ever saw".[23]

It has also been acclaimed by modern-day film historians and critics, and has often been included in lists of the most prominent experimental films.[43] Brian Taves called it a "landmark" of avant-garde film,[11] and said: "A Hollywood Extra was something entirely new, in both style and substance; more than any other American film, it initiated the avant-garde in this country."[58] Film historian William Moritz called it "a genuine little masterpiece",[13] and "perhaps the most famous American experimental film of the 1920s".[59] Hye Seung Chung, a film professor at Colorado State University, called the film an "early American avant-garde masterpiece" and described Florey as "one of the most undeservingly neglected B film auteurs".[60] David E. James called it the "prototypical 20th-century avant-garde film",[57] and wrote that A Hollywood Extra's successful commercial distribution indicates experimental films were acceptable among a popular audience during its time period, "rather than only an elite or mandarin audience".[18] Director and author Lewis Jacobs wrote: "Its style, broad and impressionistic, disclosed a remarkable sensitivity and resourcefulness in the use of props, painting, camera, and editing."[31]

The entirety of the original A Hollywood Extra has not survived.[25] In 1997, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[61] The film has been restored and released on two DVD collections: Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant Garde Film 1894–1941, by Image Entertainment,[62] and Avant-Garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and 1930s, by Kino International.[63] In 1996, the BFI commissioned composer David Sawer to write a score for the film. It and first performed by the Matrix Ensemble, conducted by Robert Ziegler. The work, called Hollywood Extra, is scored for eight musicians and was published by Universal Edition.[64]

Remake

The Life and Death of 9413: a Hollywood Extra was adapted into a remake called Hollywood Boulevard (1936), which was co-written and directed by Florey.[51][65][66] Like in the original film, the remake's central character is an actor seeking a job in Hollywood, who is subjected to the cruelties of the film industry and the whims of studio executives and film producers.[51][67] Hollywood Boulevard also includes some visual similarities to the original film, such as unusual angles to reflect the disordered nature of Hollywood.[51] However, the remake includes several subplots that lengthen the running time of the film and make it more attractive to mass audiences,[56][67] which Brian Taves said "tend(s) to diminish the importance of the central characterization, depriving Hollywood Boulevard of the singleness of purpose that made A Hollywood Extra so unforgettable".[67]

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Zecevic 1983, p. 11

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 James 2005, p. 39

- 1 2 3 4 5 James 2001, p. 51

- 1 2 Taves 1998, p. 116

- 1 2 3 4 Taves 1987, p. 88

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Taves 1987, p. 86

- ↑ Taves 1987, p. 80

- 1 2 3 4 Taves 1998, p. 95

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Eagan 2010, p. 141

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Weinberg 1929, p. 866

- 1 2 Taves 1998, p. 94

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Taves 1998, p. 96

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Moritz 1996, p. 216

- 1 2 3 "Projection Jottings: Film Made for $94 Impresses Chaplin". The New York Times. April 15, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ↑ Dixon 2015, p. 97

- ↑ Merritt 2000, p. 52

- ↑ Bawden 1976, p. 694

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 James 2005, p. 43

- 1 2 Watson 1929, p. 848

- 1 2 3 4 5 Weinberg 1929, p. 879

- ↑ Taves 1998, pp. 95–96

- ↑ Taves 1987, p. 83

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Taves 1998, p. 98

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Taves 1998, p. 97

- 1 2 3 4 Slide 2012, p. 48

- 1 2 3 4 James 2005, p. 42

- ↑ Wollstein 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Spears 1960, p. 216

- 1 2 3 Taves 1987, p. 84

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 James 2005, p. 40

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jacobs 2002, p. 9

- ↑ Taves 1987, p. 89

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Weinberg 1929, p. 867

- 1 2 3 4 Watson 1929, p. 887

- 1 2 Watson 1929, p. 888

- 1 2 3 Allen 1983, p. 12

- 1 2 3 Zimmerman 1995, p. 88

- ↑ Slide 2012, pp. 48–49

- 1 2 3 Slide 2012, p. 49

- ↑ James 2005, pp. 40–41

- ↑ Taves 1987, p. 91

- ↑ Jacobs 2002, p. 10

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 James 2005, p. 41

- ↑ Taves 2001, p. 103

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Eagan 2010, p. 142

- 1 2 Glassgold 1928, p. 290

- 1 2 Taves 1984, p. 19

- ↑ Posner 2001, p. 39

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Zecevic 1983, p. 12

- ↑ James 2001, p. 47

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Taves 1998, p. 99

- ↑ Moritz 1996, p. 217

- 1 2 Taves 1998, p. 117

- 1 2 3 4 Taves 1998, p. 113

- 1 2 Taves 1998, p. 93

- 1 2 Taves 1987, p. 193

- 1 2 James 2005, p. 47

- ↑ Taves 1998, p. 114

- ↑ Moritz 1996, p. 214

- ↑ Chung 2006, p. 67

- ↑ "New to the National Film Registry". Library of Congress. December 1997. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ↑ Krinsky 2005

- ↑ Erickson 2005

- ↑ "David Sawer: Hollywood Extra". Universal Edition. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ↑ Posner 2001, p. 19

- ↑ Giovacchini 2001, p. 23

- 1 2 3 Taves 1987, p. 198

Bibliography

- Allen, Richard (1983). "The Life and Death of 9413, a Hollywood Extra". Framework: The Journal of Cinema & Media. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. 21.

- Bawden, Liz-Anne, ed. (1976). The Oxford Companion to Film. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192115413.

- Chung, Hye Seung (2006). Hollywood Asian: Philip Ahn and the Politics of Cross-Ethnic Performance. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 1592135161.

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston Dixon (2015). "The 1940s: A Black-and-White World". Black and White Cinema: A Short History. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 081357241X.

- Eagan, Daniel (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0826429777.

- Erickson, Glenn (June 29, 2005). "Avant Garde - Experimental Cinema of the 1920s & 1930s". DVD Talk. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- Glassgold, C. Adolph (1928). "9413". The Arts. New York City: The Arts Publishing Corporation.

- Giovacchini, Saverio (2001). "Modernism, Intellectual Immigrants, and the Rebirth of Hollywood". Hollywood Modernism: Film & Politics In Age Of New Deal. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 1566398630.

- Jacobs, Lewis (2002). "Experimental Cinema in America: Part One: 1921–1941". In Martin, Ann; Smoodin, Eric. Hollywood Quarterly: Film Culture in Postwar America, 1945–1957. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0520232747.

- James, David E. (2001). "Hollywood Extras: One Tradition of "Avant-Garde" Film in Los Angeles". Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1893–1941. New York City: Anthology Film Archives. ISBN 0962818178.

- James, David E. (2005). The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0520242580.

- Krinsky, Tamar (November 2005). "'Unseen Cinema' Unveiled: Seven-DVD Set of Early Avant-Garde Rarities Released Through Image Entertainment". International Documentary Association. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- Merritt, Greg (2000). Celluloid Mavericks: A History of American Independent Film Making. New York City: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1560252324.

- Moritz, William (1996). "Visual Music and Film-as-an-Art before 1950". On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900–1950. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0520088506.

- Posner, Bruce (2001). Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1893–1941. New York City: Anthology Film Archives. ISBN 0962818178.

- Slide, Anthony (2012). Hollywood Unknowns: A History of Extras, Bit Players, and Stand-Ins. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1617034746.

- Spears, Jack (April 1960). "Robert Florey". Films in Review. New York City: National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. 11.

- Taves, Brian (May 1984). "Early Years, 1900–1928". Robert Florey: The French Expressionist: A Critical Biography (Thesis). University of Southern California. Docket Cin '84 T234 3075H3.63. Archived from the original on November 13, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- Taves, Brian (1987). Robert Florey: The French Expressionist. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810819295.

- Taves, Brian (1998). "Robert Florey and the Hollywood Avant-Garde". Lovers of Cinema: The First American Film Avant-Garde, 1919–1945. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299146847.

- Taves, Brian (2001). "Robert Florey and the Hollywood Avant-Garde". Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1893–1941. New York City: Anthology Film Archives. ISBN 0962818178.

- Watson, J.S. Jr. (January 1929). "The Amateur Takes Leadership: How Experimenters, in Circumventing Production Difficulties, Have Achieved the Greatest Cinematic Advance Since 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari'". Movie Makers. 4 (1).

- Weinberg, Herman G. (January 1929). "A Paradox of the Photoplay: A Professional Turns Amateur and Wins Professional Status". Movie Makers. 4 (1).

- Wollstein, Hans J. (2010). "Jules Raucourt". The New York Times. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- Zecevic, Bozidar (1983). "Archeology of a Film Extra: Slavko Vorkapich: A Hollywood Extra". Framework: The Journal of Cinema & Media. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. 21.

- Zimmerman, Patricia R. (1995). Reel Families: A Social History of Amateur Film. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253209447.

External links

- The Life and Death of 9413: a Hollywood Extra at the Internet Movie Database

- The Life and Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra at SilentEra