The Little Shop of Horrors

| The Little Shop of Horrors | |

|---|---|

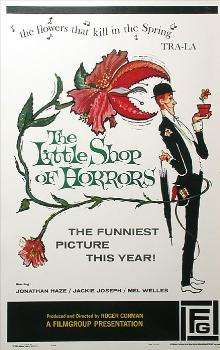

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roger Corman |

| Produced by | Roger Corman |

| Screenplay by | Charles B. Griffith |

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | Wally Campo |

| Music by | |

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | Marshall Neilan, Jr. |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Filmgroup |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 72 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $28,000[2] |

| Box office | 25,066 admissions (France)[3] |

The Little Shop of Horrors is a 1960 American black comedy horror film directed by Roger Corman. Written by Charles B. Griffith, the film is a farce about an inadequate florist's assistant who cultivates a plant that feeds on human flesh and blood. The film's concept is thought to be based on a 1932 story called "Green Thoughts", by John Collier, about a man-eating plant.[4] However, Dennis McDougal in Jack Nicholson's biography suggests that Griffith may have been influenced by Arthur C. Clarke's sci-fi short story 'The Reluctant Orchid'.[5]

The film stars Jonathan Haze, Jackie Joseph, Mel Welles, and Dick Miller, all of whom had worked for Corman on previous films. Produced under the title The Passionate People Eater,[6][7] the film employs an original style of humor, combining black comedy with farce[8] and incorporating Jewish humor and elements of spoof.[9] The Little Shop of Horrors was shot on a budget of $28,000 in two days utilizing sets that had been left standing from A Bucket of Blood.[10][11][12][13]

The film slowly gained a cult following through word of mouth when it was distributed as the B movie in a double feature with Mario Bava's Black Sunday[10][14] and eventually with The Last Woman on Earth.[10] The film's popularity increased with local television broadcasts,[15] in addition to the presence of a young Jack Nicholson, whose small role in the film has been prominently promoted on home video releases of the film.[16] The film was the basis for an Off Broadway musical, Little Shop of Horrors, which was notably made into a 1986 feature film and enjoyed a 2003 Broadway revival, all of which have attracted attention to the 1960 film.

Plot

On Los Angeles's skid row, penny-pinching Gravis Mushnick (Mel Welles) owns a florist shop which is staffed by him and his two employees, the sweet but simple Audrey Fulquard (Jackie Joseph) and clumsy Seymour Krelboyne (Jonathan Haze).[17] Although the rundown shop gets little business, there are some repeat customers; for instance, Mrs. Siddie Shiva (Leola Wendorff) shops almost daily for flower arrangements for her many relatives' funerals. Another regular customer is Burson Fouch (Dick Miller), who eats the plants he buys for lunch. When Seymour fouls up the arrangement of Dr. Farb (John Shaner), a sadistic dentist, Mushnick fires him. Hoping Mushnick will change his mind, Seymour tells him about a special plant that he crossbred from a butterwort and a Venus flytrap. Bashfully, Seymour admits that he named the plant "Audrey Jr.", a revelation that delights the real Audrey.

From the apartment he shares with his hypochondriac mother, Winifred (Myrtle Vail), Seymour fetches his odd-looking, potted plant, but Mushnick is unimpressed by its sickly, drooping look. However, when Fouch suggests that Audrey Jr.'s uniqueness might attract people from all over the world to see it, Mushnick gives Seymour one week to revive it. Seymour has already discovered that the usual kinds of plant food do not nourish his strange hybrid and that every night at sunset the plant's leaves open up. When Seymour accidentally pricks his finger on another thorny plant, Audrey Jr. opens wider, eventually causing Seymour to discover that the plant craves blood. After that, each night Seymour nurses his creation with blood from his fingers. Although he feels increasingly listless, Audrey Jr. begins to grow and the shop's revenues increase due to the curious customers who are lured in to see the plant.

The plant (voiced by writer Charles B. Griffith) develops the ability to speak and demands that Seymour feed it. Now anemic and not knowing what to feed the plant, Seymour takes a walk along a railroad track. When he carelessly throws a rock to vent his frustration, he inadvertently knocks out a man who falls on the track and is run over by a train. Miserably guilt-ridden but resourceful, Seymour collects the body parts and feeds them to Audrey Jr. Meanwhile, at a restaurant, Mushnick discovers he has no money with him, and when he returns to the shop to get some cash, he secretly observes Seymour feeding the plant. Although Mushnick intends to tell the police, he procrastinates by the next day when he sees the line of people waiting to spend money at his shop.

When Seymour later arrives that morning suffering a toothache, Mushnick sends Seymour to Dr. Farb, who tries to remove several of his teeth without anesthetic to get even with Seymour for ruining Farb's flowers. Grabbing a sharp tool, Seymour fights back and accidentally stabs and kills Farb. Seymour is horrified that he has now murdered twice and after posing as a dentist to avoid the suspicion of Farb's masochistic patient Wilbur Force (Jack Nicholson), Seymour feeds Farb's body to Audrey Jr. The unexplained disappearance of the two men attract the attention of the police and Mushnick finds himself questioned by Sergeant Joe Fink (Wally Campo) and his assistant Officer Frank Stoolie (Jack Warford) (take-offs of Dragnet characters Joe Friday and Frank Smith,[12]). Although Mushnick acts suspiciously nervous, Fink and Stoolie conclude that he knows nothing. Audrey Jr., which has grown several feet tall, is beginning to bud, as is the relationship between Seymour and Audrey (whom Seymour invites on a date).

When a representative of the Society of Silent Flower Observers of Southern California comes to the shop to check out the plant, she announces that Seymour will soon receive a trophy from them and that she will return when the plant's buds open. While Seymour is on a date with Audrey, Mushnick stays at the shop to see that Audrey Jr. eats no one else. After trading barbs with the plant when Audrey awakens and requests to be fed, Mushnick finds himself at the mercy of a robber (Charles B. Griffith) that pretended to be a customer the previous day who believes that the huge crowd he had observed attending the shop indicated the presence of a large amount of money. To save his own life, Mushnick tricks the robber into thinking that the money is inside the plant, which then crushes and eats him. Not only does the monstrous plant's growth increase with this latest meal, but its intelligence and abilities do as well. It intimidates Mr. Mushnick, who is now more terrified than ever, but not so much that he will pass up on the money the plant is bringing in as an attraction. After he is forced to damage his relationship with Audrey to keep her from discovering the plant's nature, an angry Seymour confronts the plant asserting he will no longer do its bidding just because it orders him. The plant then employs hypnosis on the feckless lad and commands him to bring it more food. He wanders the night streets aimlessly until pursued by a rather aggressively persistent street walker, Leonora Clyde (Meri Welles), intent on making a score. Believing him harmless, she flirts with him to no avail until he inadvertently knocks her out with a rock and carries her back to feed Audrey Jr.

Still lacking clues about the mysterious disappearances of the two men, Fink and Stoolie attend a special sunset celebration at the shop during which Seymour is to be presented with the trophy and Audrey Jr.'s buds are expected to open. As the attendees look on, four buds open and inside each flower is the face of one of the plant's victims. As the crowd breaks out in shock and fright, Fink and Stoolie realize Seymour is their culprit who flees from the shop with the police in hot pursuit. Managing to lose them in a junk yard filled with sinks and toilets with the help of Mushnick who followed along, Seymour eventually makes his way back to Mushnick's shop. Audrey Jr. demands, "Feed me!" Seymour curses the plant for ruining his life. He grabs a kitchen knife and climbs into Audrey Jr.'s maw, saying, "I'll feed you like you never been fed before!"

Later that evening, Audrey, Winifred, Mushnick, Fink, and Stoolie return to the shop where they discover that Audrey Jr. has begun to wither and die. As Winifred laments over how her son used to be such a good boy, one final bud opens to reveal the face of Seymour, which pitifully moans, "I didn't mean it!" before drooping over—apparently ending the life of Audrey, Jr.

Cast

- Jonathan Haze as Seymour Krelboyne

- Jackie Joseph as Audrey Fulquard

- Mel Welles as Gravis Mushnick

- Dick Miller as Burson Fouch

- Myrtle Vail as Winifred Krelboyne

- Tammy Windsor as Shirley

- Toby Michaels as Shirley's friend

- Leola Wendorff as Mrs. Siddie Shiva

- Lynn Storey as Mrs. Hortense Fishtwanger

- Wally Campo as Sergeant Joe Fink

- Jack Warford as Officer Frank Stoolie

- Meri Welles as Leonora Clyde (credited as Merri Welles)

- John Shaner as Dr. Phoebus Farb

- Jack Nicholson as Wilbur Force

- Dodie Drake as Waitress

- Charles B. Griffith as Voice of Audrey Junior, Kloy, drunk dental patient, screaming patient, flower shop robber

Development

The Little Shop of Horrors was developed when director Roger Corman was given temporary access to sets that had been left standing from a previous film. Corman decided to use the sets in a film made in the last two days before the sets were torn down.[6][7][10][11][12]

Corman initially planned to develop a story involving a private investigator. In the initial version of the story, the character that eventually became Audrey would have been referred to as "Oriole Plove". Actress Nancy Kulp was a leading candidate for the part.[10] The characters that eventually became Seymour and Winifred Krelboyne were named "Irish Eye" and "Iris Eye."[10] Actor Mel Welles was scheduled to play a character named "Draco Cardala", Jonathan Haze was scheduled to play "Archie Aroma," and Jack Nicholson would have played a character named "Jocko".[10]

Charles B. Griffith wanted to write a horror-themed comedy film. According to Mel Welles, Corman was not impressed by the box office performance of A Bucket of Blood, and had to be persuaded to direct another comedy.[7]

Corman later claimed he was interested because of A Bucket of Blood and said the development process was similar to that of the earlier film, when he and Griffith were inspired by visiting various coffee houses. Corman:

We tried a similar approach for The Little Shop of Horrors, dropping in and out of various downtown dives. We ended up at a place where Sally Kellerman (before she became a star) was working as a waitress, and as Chuck and I vied with each other, trying to top each other’s sardonic or subversive ideas, appealing to Sally as a referee, she sat down at the table with us, and the three of us worked out the rest of the story together.[18]

The first screenplay Griffith wrote was Cardula, a Dracula-themed story involving a vampire music critic.[14] After Corman rejected the idea, Griffith says he wrote a screenplay titled Gluttony,[14] in which the protagonist was "a salad chef in a restaurant who would wind up cooking customers and stuff like that, you know? We couldn’t do that though because of the code at the time. So I said, “How about a man-eating plant?”, and Roger said, “Okay.” By that time, we were both drunk."[8]

Jackie Joseph later recalled "at first they told me it was a detective movie; then, while I was flying back [to make the movie], I think they wrote a whole new movie, more in the horror genre. I think over a weekend they rewrote it."[19]

The screenplay was written under the title The Passionate People Eater.[6][7][10] Welles stated, "The reason that The Little Shop of Horrors worked is because it was a love project. It was our love project."[7]

Production

The film was partially cast with stock actors that Corman had used in previous films. Writer Charles B. Griffith portrays several small roles. Griffith's father appeared as a dental patient, and his grandmother, Myrtle Vail appeared as Seymour's hypochondriac mother.[6][14] Dick Miller, who had starred as the protagonist of A Bucket of Blood was offered the role of Seymour, but turned it down, instead taking the smaller role of Burson Fouch.[7][10] The cast rehearsed for three weeks before filming began.[14] Principal photography of The Little Shop of Horrors was shot in two days and one night.[20]

It had been rumored that the film's shooting schedule was based on a bet that Corman could not complete a film within that time. However, this claim has been denied by Mel Welles.[14] According to Joseph, Corman shot the film quickly in order to beat changing industry rules that would have prevented producers from "buying out" an actor's performance in perpetuity. On January 1, 1960, new rules were to go into effect requiring producers to pay all actors residuals for all future releases of their work. This meant that Corman's B-movie business model would be permanently changed and he would not be able to produce low-budget movies in the same way. Before these rules went into effect, Corman decided to shoot one last film and scheduled it to happen the last week in December 1959.[21]

Interiors were shot with three cameras in wide, lingering master shots in single takes.[6][10] Welles states that Corman "had two camera crews on the set—that's why the picture, from a cinematic standpoint, is really not very well done. The two camera crews were pointed in opposite directions so that we got both angles, and then other shots were 'picked up' to use in between, to make it flow. It was a pretty fixed set and it was done sort of like a sitcom is done today, so it wasn't very difficult."[14]

At the time of shooting, Jack Nicholson had appeared in two films, and had worked with Roger Corman as the lead in The Cry Baby Killer. According to Nicholson, "I went in to the shoot knowing I had to be very quirky because Roger originally hadn't wanted me. In other words, I couldn't play it straight. So I just did a lot of weird shit that I thought would make it funny."[6] According to Dick Miller, all of the dialogue between his character and Mel Welles was ad-libbed.[14] During a scene in which writer Charles B. Griffith played a robber, Griffith remembers that "When [Welles] and I forgot my lines, I improvised a little, but then I was the writer. I was allowed to."[6] However, Welles states that "Absolutely none of it was ad-libbed [...] every word in Little Shop was written by Chuck Griffith, and I did ninety-eight pages of dialogue in two days."[14]

According to Nicholson, "we never did shoot the end of the scene. This movie was pre-lit. You'd go in, plug in the lights, roll the camera, and shoot. We did the take outside the office and went inside the office, plugged in, lit and rolled. Jonathan Haze was up on my chest pulling my teeth out. And in the take, he leaned back and hit the rented dental machinery with the back of his leg and it started to tip over. Roger didn't even call cut. He leapt onto the set, grabbed the tilting machine, and said 'Next set, that's a wrap.'"[6] By 9 am of the first day, Corman was informed by the production manager that he was behind schedule.[10]

Exteriors were shot by Griffith and Welles over two successive weekends with $279 worth of rented equipment.[7][10] Griffith and Welles paid a group of children five cents apiece to run out of a subway tunnel.[14] They were also able to persuade winos to appear as extras for ten cents apiece.[7][14] "The winos would get together, two or three of them, and buy pints of wine for themselves! We also had a couple of the winos act as ramrods—sort of like production assistants—and put them in charge of the other wino extras."[14] Griffith and Welles also persuaded a funeral home to donate a hearse and coffin—with a real corpse inside—for the film shoot.[14] Griffith and Welles were able to use the nearby Southern Pacific Transportation Company yard for an entire evening using two bottles of scotch as persuasion.[7] The scene in which a character portrayed by Robert Coogan is run over by a train was accomplished by persuading the railroad crew to back the locomotive away from the actor. The shot was later printed in reverse.[7] Griffith and Welles spent a total of $1,100 on fifteen minutes worth of exteriors.[7][14]

The film's musical score, written by cellist Fred Katz, was originally written for A Bucket of Blood. According to Mark Thomas McGee, author of Roger Corman: The Best of the Cheap Acts, each time Katz was called upon to write music for Corman, Katz sold the same score as if it were new music.[22] The score was used in a total of seven films, including The Wasp Woman and Creature from the Haunted Sea.[23] Katz explained that his music for the film was created by a music editor piecing together selections from other soundtracks that he had produced for Corman.[24]

Howard R. Cohen learned from Charles B. Griffith that when the film was being edited, "there was a point where two scenes would not cut together. It was just a visual jolt, and it didn't work. And they needed something to bridge that moment. They found in the editing room a nice shot of the moon, and they cut it in, and it worked. Twenty years go by. I'm at the studio one day. Chuck comes running up to me, says, 'You've got to see this!' It was a magazine article—eight pages on the symbolism of the moon in Little Shop of Horrors."[7] According to Corman, the total budget for the production was $30,000.[13] Other sources estimate the budget to be between $22,000 and $100,000.[7][10][12]

Release and reception

Release history

Corman had initial trouble finding distribution for the film, as some distributors, including American International Pictures, felt that the film would be interpreted as anti-Semitic, citing the characters of Gravis Mushnick and Siddie Shiva.[7][10][14][25] Welles, who is Jewish, stated that he gave his character a Turkish Jewish accent and mannerisms, and that he saw the humor of the film as playful, and felt there was no intent to defame any ethnic group.[7] The film was finally released by Corman's own production company, The Filmgroup Inc., nine months after it had been completed.[14]

The film was screened out of competition at the 1960 Cannes Film Festival.[6][12] Positive word-of-mouth for the film was spread when it was released as part of a double feature preceded by Mario Bava's Black Sunday.[14] Little Shop of Horrors was re-released the following year in a double feature with The Last Woman on Earth.[10]

Because Corman did not believe that The Little Shop of Horrors had much financial prospect after its initial theatrical run, he did not bother to copyright it, resulting in the film falling into the public domain.[10][26][27] Because of this, the film is widely available in copies of varying quality. The film was originally screened theatrically in the widescreen aspect ratio of 1.85:1, but has largely only been seen in open matte at an aspect ratio of 1.33:1 since its original theatrical release.[28]

Critical and audience reception

The film's critical reception was largely favorable, with modern review aggregate Rotten Tomatoes giving the film a "Tomatometer" score of 91%.[29] Variety wrote, "The acting is pleasantly preposterous. [...] Horticulturalists and vegetarians will love it."[30]

Jack Nicholson, recounting the reaction to a screening of the film, states that the audience "laughed so hard I could barely hear the dialogue. I didn't quite register it right. It was as if I had forgotten it was a comedy since the shoot. I got all embarrassed because I'd never really had such a positive response before."[6]

Legacy

The film's popularity slowly grew with local television broadcasts throughout the 1960s and 1970s.[15]

Interest in the film was rekindled when a stage musical called Little Shop of Horrors was produced in 1982.[7] It was based on the original film and was itself adapted to cinema as Little Shop of Horrors, in 1986.[31] A short-lived animated television series inspired by the musical film, Little Shop, premiered in 1991.[32]

The film was colorized twice, the first time in 1987.[33] This version was poorly received. The film was colorized again by Legend Films, who released their color version as well as a restored black-and-white version of the film on DVD in 2006.[34][35] Legend Films' colorized version was well received,[36][37] and was also given a theatrical premiere at the Coney Island Museum on May 27, 2006.[38] The DVD included an audio commentary track by comedian Michael J. Nelson of Mystery Science Theater 3000 fame.[16][36] A DivX file of Legend's colorized version with the commentary embedded is also available as part of Nelson's RiffTrax On Demand service.[39] On January 28, 2009, a newly recorded commentary by Nelson, Kevin Murphy and Bill Corbett was released by RiffTrax in MP3 and DivX formats.[40] Legend's colorized version is also available from Amazon Video on Demand, without Nelson's commentary.[41]

In November 2006, the film was issued by Buena Vista Home Entertainment in a double feature with The Cry Baby Killer (billed as a Jack Nicholson double feature) as part of the Roger Corman Classics series. However, the DVD contained only the 1987 colorized version of The Little Shop of Horrors, and not the original black-and-white version.[42]

It was announced on April 15, 2009 that Declan O'Brien would helm a studio remake of the film.[43] "It won't be a musical" he told Bloody Disgusting in reference to the Frank Oz film from 1986. "I don't want to reveal too much, but it's me. It'll be dark."[44] When speaking with Shock 'Till You Drop, he revealed "I have a take on it you're not going to expect. I'm taking it in a different direction, let's put it that way."[45]

See also

References

- ↑ "The Little Shop of Horrors (A)". British Board of Film Classification. March 1, 1973. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ↑ Fred Olen Ray, The New Poverty Row: Independent Filmmakers as Distributors, McFarland, 1991, p 28-29

- ↑ Box office information for Roger Corman films in France at Box Office Story

- ↑ Fowler, Christopher. "Forgotten authors No. 34: John Collier". The Independent, May 24, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2010

- ↑ McDougal, Dennis (2008). Five Easy Decades: How Jack Nicholson Became the Biggest Movie Star in Modern Times. John Wiley & Sons. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-471-72246-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Corman, Roger; Jerome, Jim. How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime. Da Capo Press. pp. 61–62; 67–70. ISBN 0-306-80874-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Gray, Beverly (2004). Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers. Thunder's Mouth Press. pp. 62–65, 67–69. ISBN 1-56025-555-2.

- 1 2 Graham, Aaron W. "Little Shop of Genres: An interview with Charles B. Griffith". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ Weaver, James B.; Tamborini, Ronald C., eds. (1996). Horror Films: Current Research on Audience Preferences and Reactions. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Ray, Fred Olen (1991). The New Poverty Row: Independent Filmmakers As Distributors. McFarland & Company. pp. 28–30. ISBN 0-89950-628-3.

- 1 2 "Fun Facts". A Bucket of Blood (Media notes). MGM Home Entertainment. 2000. UPC:027616852847.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Peary, Danny (1981). Cult Movies. New York: Delacorte Press. pp. 203–205. ISBN 0-440-01626-6.

- 1 2 Simpson, MJ (September 23, 1995). "Interview with Roger Corman". Retrieved 2007-10-24.

I shot Little Shop of Horrors in two days and a night for about $30,000, and the picture has lasted all these years.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Weaver, Tom (1999). Return of the B Science Fiction and Horror Movie Makers: Writers, Producers, Directors, Actors, Moguls and Makeup. McFarland & Company. pp. 387–390.

- 1 2 Hogan, David J. (1997). Dark Romance: Sexuality in the Horror Film. McFarland & Company. p. 224. ISBN 0-7864-0474-4.

- 1 2 Pearce, Joel (June 16, 2006). "Review of The Little Shop of Horrors'". DVD Verdict. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ "IMDb". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- ↑ Roger Corman, "Wild Imagination: Charles B. Griffith 1930-2007", LA Weekly 17 October 2007 accessed 20 April 2014

- ↑ Tom Weaveer, Jackie Joseph interview, B Monster accessed 18 April 2014

- ↑ Anderson, Porter (January 4, 2001). "Roger Corman: Attack of the independent filmmaker". CNN. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ Weaver, Tom. "Interview with Jackie Joseph". The Astounding B Monster. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ Ray, Fred Olen (1991). The New Poverty Row: Independent Filmmakers As Distributors. McFarland & Company. p. 40. ISBN 0-89950-628-3.

- ↑ "Fred Katz filmography". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ↑ Larson, R. D., A talk with Fred Katz by Randall D. Larson, Originally published in CinemaScore #11/12, 1983

- ↑ Halligan, Benjamin (2003). Michael Reeves. Manchester University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-7190-6351-5.

- ↑ Fishman, Stephen (2010), The Public Domain: How to Find & Use Copyright-Free Writings, Music, Art & More (5th ed.), Nolo (retrieved via Google Books), ISBN 1-4133-1205-5, retrieved 2010-10-31

- ↑ David, Pierce (June 2007). "Forgotten Faces: Why Some of Our Cinema Heritage Is Part of the Public Domain". Film History: An International Journal. 19 (2): 125–43. doi:10.2979/FIL.2007.19.2.125. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 25165419. OCLC 15122313.

- ↑ Dante, Joe. Notes from Joe: Aspect Ratios in THE LITTLE SHOP OF HORROR. Trailers From Hell. 2011.

- ↑ "The Little Shop of Horrors reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ↑ Staff (December 31, 1960). "The Little Shop of Horrors". Variety. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ↑ "Little Shop of Horrors (1986)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ "Little Shop (1991)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ "ASIN: B0009LD2N2". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ "'Little Shop of Horrors' Now in Color". Legend Films. PR Newswire. May 11, 2006. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ "ASIN: B000FAOCFE". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- 1 2 Gibron, Bill (May 21, 2006). "The Little Shop of Horrors: In Color (with Mike Nelson Commentary)". DVD Talk. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ "The Little Shop of Horrors". DVD Beaver. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ "Coney Island USA Events Calendar". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ "Little Shop of Horrors VOD". RiffTrax. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ "The Little Shop of Horrors – Three Riffer Edition!". RiffTrax. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ "ASIN: B001L2BIU2". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ "ASIN: B000HA4WQQ". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ Bartyzel, Monika. "Non-Musical Remake of 'Little Shop of Horrors' Coming!". Cinematical. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- ↑ "Wrong Turn 3 Opens His 'Little Shop of Horrors'". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- ↑ Rotten, Ryan. "Little Shop of Horrors Re-Opening for Business". Shock 'Till You Drop. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Little Shop of Horrors. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Little Shop of Horrors |

- The Little Shop of Horrors at the Internet Movie Database

- The Little Shop of Horrors is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The Little Shop of Horrors at AllMovie

- The Little Shop of Horrors at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Little Shop of Horrors on YouTube

- The Little Shop of Horrors at Legend Films

- Joe Dante on The Little Shop of Horrors at Trailers From Hell

- The Little shop of Horrors Movie Review