Third Fitna

| Third Fitna | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Fitnas | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| pro-Qays Umayyads | pro-Yaman Umayyads |

anti-Umayyad forces:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

Walid II † Marwan II Abu al-Ward Nasr ibn Sayyar |

Yazid III Sulayman ibn Hisham Yazid ibn Khalid al-Qasri |

Abdallah ibn Mu'awiya al-Dahhak ibn Qays al-Shaybani † Hafs ibn al-Walid ibn Yusuf al-Hadrami Abu Muslim | ||||||

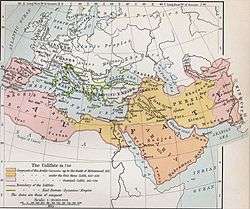

The Third Fitna (Arabic: الفتنة الثاﻟﺜـة; al-Fitna al-thālitha), was a series of civil wars and uprisings against the Umayyad Caliphate beginning with the overthrow of Caliph al-Walid II in 744 and ending with the victory of Marwan II over the various rebels and rivals for the caliphate in 747. However, Umayyad authority under Marwan II was never fully restored, and the civil war flowed into the Abbasid Revolution (746–750) which culminated in the overthrow of the Umayyads and the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate in 749/50. Thus a clear chronological delimitation of this conflict is not possible.[1]

Usurpation of Yazid III

The civil war began with the overthrow of al-Walid II (743–744), the son of Yazid II (r. 720–724). Al-Walid had been designated by his father as the successor of his brother Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (r. 724–743), and although his accession had initially been well received due to Hisham's unpopularity and his decision to increase army pay, the mood quickly changed. Al-Walid is reported to have been more interested in earthly pleasures than in religion, a reputation that may be confirmed by the decoration of the so-called "desert palaces" (including Qusayr Amra and Khirbat al-Mafjar) that have been attributed to him.[2] His accession was resented by some members of the Umayyad family itself, and this hostility deepened when al-Walid designated his two underage sons as his heirs and flogged and imprisoned his cousin, Sulayman ibn Hisham.[3] Further opposition arose through his persecution of the Qadariyya sect,[4] and through his implication in the ever-present rivalry between the northern (Qaysi and Mudari) and southern (Kalbi and Yemeni) Arab tribes. Like his father, al-Walid was seen as pro-Qays, especially following his appointment of Yusuf ibn Umar al-Thaqafi as governor of Iraq, and the torture and death of Yusuf's Yemeni predecessor, Khalid al-Qasri. It must be noted though that adherence was not clear cut, and men from both sides of the divide joined the other.[5]

In April 744, Yazid III, a son of al-Walid I (r. 705–715), entered Damascus. His supporters, bolstered by many Kalbis from the surrounding region, seized the town and proclaimed him caliph. Al-Walid II, who was at one of his desert palaces, fled to al-Bakhra near Palmyra. He mustered a small force of local Kalbis and Qaysis from Hims, but when Yazid III's far larger army under Abd al-Aziz ibn al-Hajjaj ibn Abd al-Malik arrived, most of his adherents fled. Al-Walid II was killed, and his severed head sent to Damascus.[6] A pro-Qaysi uprising in Hims followed, under the Sufyanid Abu Muhammad al-Sufyani, but its march on Damascus was decisively defeated by the released Sulayman ibn Hisham. Abu Muhammad was thrown into prison in Damascus along with al-Walid II's sons.[7]

During his brief reign, Yazid showed himself an exemplary ruler, modelling himself on the pious Umar II (r. 717–720). He was favourably disposed to the Qadariyya, and consciously tried to disassociate himself from the frequent criticism of autocratic rule levelled at his Umayyad predecessors. Thus he promised to refrain from abuses of his power—mostly concerning widespread resentment at heavy taxation, the enrichment of the Umayyads and their adherents, the preference given to Syria over other parts of the Caliphate, and the long absence of soldiers on distant campaigns—and insisted that not only was he chosen by the community in an assembly (shura), rather than appointed, but that the community had the right to depose him if he failed in his duties or if they found someone more fit to lead them.[8] At the same time, his reign saw the renewed ascendancy of the Yemenis, with Yusuf ibn Umar dismissed and imprisoned after trying, without success, to raise the Qaysis of Iraq into revolt. Yusuf's successor in Iraq and the East was the Kalbi Mansur ibn Jumhur, but he was soon replaced by the son of Umar II, Abdallah ibn Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz. During his brief tenure, Mansur tried to dismiss the governor of Khurasan, Nasr ibn Sayyar, but the latter managed to maintain his post.[9] Yazid died in September 744 after a reign of barely six months. Apparently due to the advice of the Qadariyya, he had appointed his brother, Ibrahim, as his successor, but he did not enjoy much support and was immediately faced with the revolt of Marwan II (r. 744–750), the grandson of Marwan I (r. 684–685) and governor of Upper Mesopotamia.[9]

Rise of Marwan II

Marwan, who had for several years supervised the campaigns against the Byzantine Empire and the Khazars on the Caliphate's northwestern frontiers, had reportedly considered claiming the caliphate already at the death of al-Walid II, but a Kalbi rebellion in his rear had forced him to turn back. Yazid III appointed him to Upper Mesopotamia, and Marwan installed himself in the Qays-dominated city of Harran.[10]

Syria

Following Yazid's death, Marwan marched into Syria, at first claiming that he came as the champion of al-Walid II's imprisoned sons. The local Qaysis of the northern districts of Qinnasrin and Hims flocking to his banner, until at some point on the road leading from Baalbek to Damascus, Marwan was confronted by Sulayman ibn Hisham. Likewise an experienced commander, Sulayman was at the head of his Dhakwaniyya private army and the Kalbis of southern Syria, but Marwan emerged victorious, with Sulayman fleeing to Damascus.[11] Marwan obliged the captives from Sulayman's army to pledge allegiance to al-Walid II's sons, whereupon they were killed by Yazid ibn Khalid al-Qasri on Sulayman's orders, along with Yusuf al-Thaqafi. Sulayman and his adherents, including the caliph-designate Ibrahim, then fled to Palmyra.[11]

Marwan was thus able to enter Damascus peacefully in December 944, and was declared caliph. Marwan avoided reprisals and followed a conciliatory policy, allowing the Syrian districts (ajnad) to choose their own governors. After a short while, Sulayman ibn Hisham and Ibrahim likewise gave up their resistance and came to Damascus to submit.[12] Marwan's hold on power seemed secure, but he then chose to move his capital from Damascus to the military centre of Harran. As Gerald Hawting writes, "[f]or the first time a caliph seemed to have abandoned Syria altogether", and this act only served to fuel mistrust and resentment by the defeated Kalbis against Marwan.[13] As a result, in summer 745 the Kalbis of Palestine rose in revolt under the local governor, Thabit ibn Nu'aym—the same man who had led the Kalbi mutiny against Marwan earlier in the year. The revolt soon spread across Syria, event to ostensibly loyal Qaysi areas like Hims. Marwan was thus obliged to return to Syria and reduce the uprising city by city. After forcing Hims to surrender, Marwan relieved Damascus from its siege by Yazid ibn Khalid al-Qasri, who was killed. He then rescued Tiberias, which was being besieged by Thabit ibn Nu'aym, and proceeded to defeat, capture and execute both Thabit and his sons. Following Marwan's attack on the Kalbi stronghold of Palmyra, the Kalbi leader Abrash al-Kalbi also made terms.[14]

With Syria apparently back in his grip, Marwan ordered the members of the Umayyad dynasty to gather around him and named his two sons as his heirs. Marwan then focused his attention on Iraq, where an army under Yazid ibn Hubayra was already trying to gain control of the province for him. Marwan assembled a new army to send to Ibn Hubayra's aid, but at Rusafa it mutinied, and accepted Sulayman ibn Hisham as its leader. The rebel army took Qinnasrin, and once again many Syrians dissatisfied with Marwan joined them, but Marwan brought the bulk of his forces from Iraq and defeated the rebels near Qinnasrin. Sulayman ibn Hisham was able to escape again to Palmyra, and thence fled to Kufa, but most of his surviving troops withdrew to Hims under the command of his brother Sa'id, where they were soon besieged by Marwan's forces. The siege lasted through the winter of 745–746, but in the end Hims surrendered.[15] Enraged at the repeated Syrian revolts despite his earlier leniency, Marwan now, in the summer of 746, moved to prevent any further resistance by tearing down the walls of most important Syrian towns, including Damascus and possibly even Jerusalem.[15]

Egypt and Iraq

Opposition to Marwan and his Qaysis was also evident in Egypt, where the governor Hafs ibn al-Walid ibn Yusuf al-Hadrami, a member of the local Arab settler community, tried to use the turmoil of the civil war to restore its traditional dominance in Egyptian affairs: the Syrians were forcibly expelled from the capital Fustat, and Hafs set about recruiting a force of 30,000 men, named Hafsiya after him, from among the native non-Arab converts ("maqamisa" and "mawali"). Marwan sent Hasan ibn Atahiya to replace him and ordered the Hafsiya disbanded, but the latter refused to accept the order to disband and mutinied, besieging the new governor in his residence until he and his sahib al-shurta both were forced to leave Egypt. Hafs, though unwilling, was restored by the mutinous troops as governor. In the next year, 745, when Marwan dispatched a new governor, Hawthara ibn Suhayl al-Bahili, at the head of a large Syrian army. Despite his supporters' eagerness to resist, Hafs proved willing to surrender his position. Hawthara took Fustat without opposition, but immediately launched a purge, to which Hafs and several Hafsiya leaders fell victim.[16]

In the meantime, in Iraq, Marwan's rebellion coincided with an Alid uprising in Kufa, headed by Abdallah ibn Mu'awiya, in October 744. The uprising was soon suppressed by Yazid III's governor, Abdallah ibn Umar, and his Syrian troops, but Ibn Mu'awiya had managed to escape to Jibal. There volunteers opposed to the Umayyad regime continued to flock to his banner, and he managed to extend his control over large parts of Persia, including most of Jibal, Ahwaz, Fars and Kerman. He established his residence first at Isfahan and then at Istakhr.[15][17] Marwan II appointed a supporter of his own, the Qaysi Nadr ibn Sa'id al-Harashi, as governor of Iraq, but Abdallah ibn Umar retained the loyalty of the Kalbi majority of the Syrian troops, and for several months the two rival governors and their troops confronted and skirmished at each other around al-Hira.[18] This conflict was abruptly ended with the Kharijite revolt which had begun among the Banu Rabi'ah tribes in Upper Mesopotamia. Although "northerners", the Rabi'a, and especially the Banu Shayban, were enemies of the Mudar and Qays and opposed Marwan II's takeover.[19]

The revolt was initially led by Sa'id ibn Bahdal, but he died soon of the plague, and was succeeded by al-Dahhak ibn Qays al-Shaybani. In early 745 they invaded Iraq and defeated both rival Umayyad governors, who had joined forces, in April/May 745. Nadr fled back to Syria to join Marwan, but Ibn Umar and his followers withdrew to Wasit. In August 745 however Ibn Umar and his supporters surrendered and even embraced Kharijism and Dahhak—who was not even of the Quraysh tribe of Muhammad—as their caliph. Ibn Umar was appointed as Dahhak's governor for Wasit, eastern Iraq, and western Persia, while Dahhak governed western Iraq from Kufa.[19][20] Taking advantage of the Syrian revolt against Marwan, Dahhak returned to Upper Mesopotamia—probably in spring 746—and while Marwan was occupied by the siege of Hims, he seized Mosul. More men flocked to his banner, whether out of opposition to Marwan, like Sulayman ibn Hisham and the remnant of his Dhakwaniyya, or because he offered high wages to his followers, and his army is said to have reached 120,000 men. Marwan sent his son Abdallah to oppose Dahhak, but the Kharijite leader managed to blockade him in Nisibis. Once Hims had fallen, however, Marwan himself campaigned against Dahhak, and in a battle at al-Ghazz in Kafartuta in August/September 746, Dahhak was killed and the Kharijites had to abandon Upper Mesopotamia.[19][20] The Kharijites now selected Abu Dulaf as their leader, and on the advice of Sulayman ibn Hisham they withdrew to the eastern bank of the Tigris. As Marwan was able to withdraw more troops to face the Kharijites, however, they were forced to abandon even this position and withdraw further east. Marwan then sent his general Yazid ibn Hubayra to establish control over Iraq, which he accomplished this by the summer of 747: after defeating the Kharijite governor of Kufa and taking the city, Ibn Hyubayra marched on Wasit, where he took Abdallah ibn Umar prisoner.[21]

Marwan's capture of Iraq left Abdallah ibn Mu'awiya as the only major leader opposing the Umayyad caliph, and his domain in western Persia became a refuge for the defeated Kharijites of Iraq, and every other opponent of Marwan, including members of the Umayyad family—notably Sulayman ibn Hisham—and even a few Abbasids. Nevertheless, in a short time Ibn Mu'awiya's forces suffered a decisive defeat by one of Ibn Hubayra's generals. Ibn Mu'awiya fled to Khurasan, where the leader of the Abbasid Revolution, Abu Muslim, had him executed, while Sulayman ibn Hisham and Mansur ibn Jumhur fled to India, where they remained until they died.[22]

Khurasan and the Abbasid Revolution

Khurasan, the northeasternmost province of the Caliphate, had not escaped the turmoils of the civil war. Yazid III's accession posed a threat to the longtime governor, Nasr ibn Sayyar, as the numerous Yemenis in Khurasan sought to replace him with their champion, Juday al-Kirmani. Nasr tried to secure his own position by deposing al-Kirmani from his leadership of the Azd tribe, as well as by trying to win over Azd and Rabi'ah leaders. This led to a general uprising by these tribes under al-Kirmani. It is indicative of the lingering intertribal antagonism of the late Umayyad world that the rebellion was launched in the name of revenge for the Muhallabids, an Azdi family that had been purged after rebelling in 720, an act which had since become a symbol of Yemeni resentment of the Umayyads and their northern Arab-dominated regime.[23][24][25] Nasr imprisoned al-Kirmani in the provincial capital, Merv, but he managed to escape in summer 744. Despite Nasr's eventual re-confirmation as governor by Yazid, the rebellion spread among the Arabs of Khurasan, so that Nasr was forced to turn to the exiled rebel al-Harith ibn Surayj. Al-Kirmani had played a major role in the latter's defeat years ago, and Ibn Surayj's northern Arab (Tamimi) origin made him a natural enemy of the Yemenis. Ibn Surayj however had other designs; gathering a following of many of the Tamimis and the disaffected Arabs of the province, he launched an attack on Merv in March 746. After it failed, he made common cause with al-Kirmani.[26][27][28]

With Marwan II still trying to consolidate his own position in Syria and Mesopotamia, and western Persia controlled by the Kharijites under Ibn Mu'awiya, Nasr was bereft of any hopes of reinforcement. The allied armies of Ibn Surayj and al-Kirmani drove him out of Merv towards the end of the year, and he retreated to the Qaysi stronghold of Nishapur.[29][30][31] Within days al-Kirmani and Ibn Surayj fell out among themselves and clashed, resulting in the latter's death. Al-Kirmani then destroyed the Tamimi quarters in Merv, a shocking act, as dwellings were traditionally considered exempt from warfare in Arab culture. As a result, the Mudari tribes, hitherto ambivalent towards Nasr, now came over to him. Backed by them, especially the Qaysis of Nishapur, Nasr now resolved to take back the capital. During summer 747, Nasr's and al-Kirmani's armies confronted each other before the walls of Marv, occupying two fortified camps and skirmishing with each other for several months. The fighting stopped only when news came of the start of the Hashimiyya uprising under Abu Muslim. Negotiations commenced, but were almost broken off when a member of Nasr's entourage, an embittered son of Ibn Surayj, attacked and killed al-Kirmani. The two sides were able to tentatively settle their differences, and Nasr re-occupied his seat in Marv.[29][32][33]

.jpg)

The exact origins and nature of the Hashimiyya movement are debated among scholars, but by the 740s this movement, which supported the overthrow of the Umayyads and their replacement by a "chosen one from the family of Muhammad", had spread widely among the Arabs of Khurasan. In 746 or 747, Abu Muslim was sent to Khurasan by the Abbasid imam, Ibrahim, to assume the leadership of the sect there, possibly in order to bring it more under Abbasid control. In a short time Abu Muslim established his control of the Khurasani Hashimiyya, and in summer 747, at the Yemeni village of Sikadanj, the black banners were unfourled, the prayer read in the name of the Abbasid imam, and the Abbasid Revolution begun.[34] Abu Muslim soon took advantage of the barely mended Mudari–Yemeni hostility, by persuading al-Kirmani's son and successor Ali that Nasr had been involved in his father's murder. As a result, both Ali al-Kirmani and Nasr separately appealed for aid against each other to Abu Muslim, who now held the balance of power. The latter eventually chose to support the Yemenis, and on 14 February 748, Abu Muslim's army occupied Marv.[35][36] Nasr ibn Sayyar once again fled to Nishapur, while Abu Muslim sent the Hashimiyya forces under Qahtaba ibn Shabib al-Ta'i to pursue him. Nasr was forced to abandon Nishapur too after his son Tamim was defeated at Tus, and retreat to the region of Qumis, on the western borderlands of Khurasan. At this point, the long-awaited reinforcements from the Caliph arrived, but their general and Nasr failed to coordinate their movements, and Qahtaba was able to defeat the caliphal army at Gurgan in August 748 and capture Rayy.[37][38] Following the capture of Nishapur, Abu Muslim consolidated his position in Khurasan by murdering Ali ibn Juday al-Kirmani and his brother.[37]

In March 749, Qahtaba defeated another, bigger, caliphal army near Isfahan, while his son al-Hasan ibn Qahtaba led the siege of Nihawand, where the remnants of the caliphal armies and Nasr ibn Sayyar's followers made their last stand. The surrender of Nihawand opened the way to Iraq.[37][39] Qahtaba led his troops towards Kufa, but on the way they were confronted by Marwan II's governor Yazid ibn Hubayra. After a surprise night attack in which Qahtaba was killed on 27 August 749, Ibn Hubayra was forced to withdraw to Wasit, and al-Hasan ibn Qahtaba led his army into Kufa on 2 September.[39][40] As imam Ibrahim had been imprisoned and executed by Marwan II, he was succeeded by his brother, Abu'l-Abbas, whom the army leaders proclaimed as caliph on 28 November.[41] In January 750, at the Battle of the Greater Zab, the Abbasid army decisively defeated the Umayyad army led by Marwan II in person. Pursued by the Abbasids, Marwan was forced to flee to Syria and then Egypt, where he was finally captured and executed in August 750.[42]

References

- ↑ Hawting 2000, p. 90.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, p. 92.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, p. 93.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, p. 94.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 94–95.

- 1 2 Hawting 2000, p. 96.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 96–97.

- 1 2 Hawting 2000, p. 97.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, p. 98.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 97, 98–99.

- 1 2 3 Hawting 2000, p. 99.

- ↑ Kennedy 1998, pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Zetterstéen 1987, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 99–100.

- 1 2 3 Hawting 2000, p. 100.

- 1 2 Veccia Vaglieri 1991, p. 90.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, p. 101.

- ↑ Shaban 1979, p. 134.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 76, 107.

- ↑ Sharon 1990, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Shaban 1979, pp. 134–136.

- ↑ Sharon 1990, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 107–108.

- 1 2 Hawting 2000, p. 108.

- ↑ Shaban 1979, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Sharon 1990, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Shaban 1979, p. 137.

- ↑ Sharon 1990, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 109–115.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 108–109, 115.

- ↑ Shaban 1979, pp. 159–160.

- 1 2 3 Hawting 2000, p. 116.

- ↑ Shaban 1979, pp. 160–161.

- 1 2 Shaban 1979, p. 161.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, p. 117.

- ↑ Hawting 2000, pp. 117–118.

Sources

- Hawting, G. R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 (2nd Edition). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1998). "Egypt as a province in the Islamic caliphate, 641–868". In Petry, Carl F. Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume One: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–85. ISBN 0-521-47137-0.

- Shaban, M. A. (1979). The ʿAbbāsid Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29534-3.

- Sharon, Moshe (1990). Revolt: the social and military aspects of the ʿAbbāsid revolution. Jerusalem: Graph Press Ltd. ISBN 965-223-388-9.

- Veccia Vaglieri, Laura (1991). "al-Ḍaḥḥāk b. Qays al-Shaybānī". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden and New York: BRILL. p. 90. ISBN 90-04-07026-5.

- Zetterstéen, K. V. (1987). "ʿAbd Allāh b. Muʿāwiya". In Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor. E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume I: A–Bābā Beg. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 26–27. ISBN 90-04-08265-4.