Tranexamic acid

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | \ˌtran-eks-ˌam-ik-\ |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Injection and oral |

| ATC code | B02AA02 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 34% |

| Biological half-life | 3.1 h |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

1197-18-8 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5526 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 6573 |

| DrugBank |

DB00302 |

| ChemSpider |

10482000 |

| UNII |

6T84R30KC1 |

| KEGG |

D01136 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:48669 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL877 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.471 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

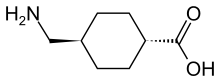

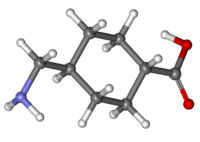

| Formula | C8H15NO2 |

| Molar mass | 157.21 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a medication used to treat or prevent excessive blood loss from trauma, surgery, and in various medical conditions including hemophilia and heavy menstrual bleeding.[1] It comes in oral and intravenous forms.[1]

Side effects are uncommon and include gastrointestinal effects, dizziness, fatigue, headache, and hypersensitivity reactions.[2] The medication needs to be used cautiously in people with kidney disease and who are at a high risk for blood clots.[1] Tranexamic is safe to use in pregnant women. However, caution should be used in lactating women.[1] It is an antifibrinolytic.

It was discovered in 1962 by Utako Okamoto[3] and has been on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[4]

Medical uses

Tranexamic acid is frequently used following major trauma.[5] Tranexamic acid is used to prevent and treat blood loss in a variety of situations, such as dental procedures for hemophiliacs, heavy menstrual bleeding, and surgeries with high risk of blood loss.[6][7]

Trauma

Tranexamic acid has been found to decrease the risk of death in people who have significant bleeding due to trauma.[8][9] Its main benefit is if taken within the first three hours.[10]

Heavy menstrual bleeding

Tranexamic acid is used to treat heavy menstrual bleeding.[7] When taken by mouth it both safely and effectively treats regularly occurring heavy menstrual bleeding.[2][11] Another study demonstrated that the dose does not need to be adjusted in females who are between ages 12 and 16.[2]

Surgery

- Tranexamic acid is used in orthopedic surgery to reduce blood loss, to the extent of reducing or altogether abolishing the need for perioperative blood collection. It is of proven value in clearing the field of surgery and reducing blood loss when given before or after surgery. Drain and number of transfusions are reduced.

- In surgical corrections of craniosynostosis in children it reduces the need for blood transfusions.[12]

- In spine surgery, e.g. scoliosis correction with posterior spinal fusion using instrumentation, to prevent excessive blood loss.[13]

- In cardiac surgery, both with and without cardiopulmonary bypass e.g. coronary artery bypass surgery, it is used to prevent excessive blood loss. It replaces aprotinin.

Dentistry

In the United States, tranexamic acid is FDA approved for short-term use in people with severe bleeding disorders who are about to have dental surgery.[1] Tranexamic acid is used for a short period of time before and after the surgery to prevent major blood loss and decrease the need for blood transfusions.[14] In people with hemophilia, combinations of tranexamic acid and factor VII or IX have effectively decreased blood loss and the need for transfusions after dental surgery In one person with mild hemophilia, a combination of tranexamic acid and demopressin effectively stopped bleeding[15]

Tranexamic acid is used in dentistry in the form of a 5% mouth rinse after extractions or surgery in patients with prolonged bleeding time, e.g. from acquired or inherited disorders.

Other uses

- In obstetrics, tranexamic acid is used after delivery to reduce bleeding, often with syntocinon/oxytocin and fundal massage. Since 2010, the WOMAN (World Maternal Antifibrinolytic) trial has been in progress worldwide to establish the efficacy of the drug to arrest postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) in 15 000 women, due to be completed in 2016.[16] Since the drug can be administered orally, it has great potential to reduce maternal mortality rates in developing countries where primary healthcare is often unavailable.

- In hereditary angioedema[17]

- In hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia - Tranexamic acid has been shown to reduce frequency of epistaxis in patients suffering severe and frequent nosebleed episodes from hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.[18]

- In melasma - Tranexamic acid has shown to provide rapid and sustained lightening in melasma by decreasing melanogenesis in epidermal melanocytes.[19]

- In hyphema - Tranexamic acid has been shown to be effective in reducing risk of secondary hemorrhage outcomes in patients with traumatic hyphema.[20]

Adverse effects

Common side effects include:[2]

- Headaches (50.4 - 60.4%)

- Back aches (20.7 - 31.4%)

- Nasal sinus problem (25.4%)

- Abdominal pain (12 - 19.8%)

- Diarrhea (12.2%)

- Fatigue (5.2%)

- Anemia (5.6%)

Rare side effects include:[2]

- Pulmonary embolism

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Anaphylaxis

- Visual disturbances

These rare side effects were reported in post marketing experience and frequencies cannot be determined.[2]

Special populations

- Tranexamic acid is categorized as pregnancy category B. No harm has been found in animal studies.[2]

- Small amounts appears in breast milk if taken during lactation.[2] If it is required for other reasons, breastfeeding may be continued.[21]

- Tranexamic acid is also not indicated for postmenopausal women and geriatrics.[2]

- In kidney impairment, tranexamic acid is not well studied. However, due to the fact that it is 95% excreted unchanged in the urine, it should be dose adjusted in patients with renal impairment.[2]

- In liver impairment, dose change is not needed as only a small amount of the drug is metabolized through the liver.[2]

Mechanism of action

Tranexamic acid is a synthetic analog of the amino acid lysine. It serves as an antifibrinolytic by reversibly binding four to five lysine receptor sites on plasminogen or plasmin. This prevents plasmin from binding to and degrading fibrin and preserves the framework of fibrin's matrix structure.[2] Tranexamic acid has roughly eight times the antifibrinolytic activity of an older analogue, ε-aminocaproic acid.

Society and culture

TXA was discovered in 1962 by Utako Okamoto.[3] It has been included in the WHO list of essential medicines.[4] TXA is inexpensive and treatment would be considered highly cost effective in high, middle and low income countries.[22]

Brand names

Tranexamic acid is marketed in the U.S. and Australia in tablet form as Lysteda and in Australia and Jordan it is marketed in an IV form and tablet form as Cyklokapron, in the UK as Cyclo-F and Femstrual, in Asia as Transcam, in Bangladesh as Traxyl, in India as Pause, in South America as Espercil, in Japan as Nicolda, in France and Romania as Exacyl and in Egypt as Kapron. In the Philippines, its capsule form is marketed as Hemostan and In Israel as Hexakapron.

Approval

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tranexamic acid oral tablets (brand name Lysteda) for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding on 13 November 2009.

In March 2011 the status of tranexamic acid for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding was changed in the UK, from PoM (Prescription only Medicines) to P (Pharmacy Medicines)[23] and became available over the counter in UK pharmacies under the brand names of Cyklo-F and Femstrual, initially exclusively for Boots pharmacy, which has sparked some discussion about availability.[24] (In parts of Europe - like Sweden - it had then been available OTC for over a decade.) Regular liver function tests are recommended when using tranexamic acid over a long period of time.[25]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Cyklokapron (tranexamic acid) Product Information" (PDF). Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Lysteda (tranexamic acid) Package Insert" (PDF). accessdata.FDA.gov. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- 1 2 Geoff Watts (2016). "Obituary Utako Okamoto". The Lancet. 387 (10035): 2286. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30697-3.

- 1 2 "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Binz, S; McCollester, J; Thomas, S; Miller, J; Pohlman, T; Waxman, D; Shariff, F; Tracy, R; Walsh, M (2015). "CRASH-2 Study of Tranexamic Acid to Treat Bleeding in Trauma Patients: A Controversy Fueled by Science and Social Media.". Journal of blood transfusion. 2015: 874920. doi:10.1155/2015/874920. PMID 26448897.

- ↑ Melvin, JS; Stryker, LS; Sierra, RJ (22 October 2015). "Tranexamic Acid in Hip and Knee Arthroplasty.". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 23: 732–40. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00223. PMID 26493971.

- 1 2 Tengborn, L; Blombäck, M; Berntorp, E (February 2015). "Tranexamic acid--an old drug still going strong and making a revival.". Thrombosis research. 135 (2): 231–42. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2014.11.012. PMID 25559460.

- ↑ Cherkas, David (Nov 2011). "Traumatic Hemorrhagic Shock: Advances In Fluid Management". Emergency Medicine Practice. 13 (11).

- ↑ "Drug will save lives of accident victims, says study". BBC News. 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ Napolitano, Lena M.; Cohen, Mitchell J.; Cotton, Bryan A.; Schreiber, Martin A.; Moore, Ernest E. (2013). "Tranexamic acid in trauma". Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 74 (6): 1575–86. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318292cc54. PMID 23694890.

- ↑ Lukes, AS; Moore, KA; Muse, KN (2010). "Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial". Obstet Gynecol. 116 (4): 865–875. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f20177. PMID 20859150.

- ↑ RCPCH. "Evidence Statement Major trauma and the use of tranexamic acid in children Nov 2012" (PDF). Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ↑ Sethna, N. F.; Zurakowski, D; Brustowicz, R. M.; Bacsik, J; Sullivan, L. J.; Shapiro, F (2005). "Tranexamic acid reduces intraoperative blood loss in pediatric patients undergoing scoliosis surgery". Anesthesiology. 102 (4): 727–32. doi:10.1097/00000542-200504000-00006. PMID 15791100.

- ↑ Forbes CD, Barr RD, Reid G; et al. (1972). "Tranexamic acid in control of haemorrhage after dental extraction in haemophilia and Christmas disease". Br Med J. 2 (5809): 311–313. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5809.311.

- ↑ Shankar S & Lee R (1984). "DDAVP and tranexamic acid for dental extractions in a mild hemophiliac". Br Dent J. 156 (12): 450–452. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4805387.

- ↑ "Protocol 09PRT/4179:Tranexamic acid for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: an international, randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial (the WOMAN Trial)". The Lancet. Elsevier Limited. n.d. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ Rod Flower; Humphrey P. Rang; Maureen M. Dale; Ritter, James M. (2007). Rang & Dale's pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-06911-5.

- ↑ Klepfish, A; Berrebi, A; Schattner, A (2001). "Intranasal tranexamic acid treatment for severe epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia". Archives of Internal Medicine. 161 (5): 767. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.5.767. PMID 11231712.

- ↑ Karn, D; Kc, S; Amatya, A; Razouria, E. A.; Timalsina, M (2012). "Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma". Kathmandu University Medical Journal. 10 (40): 40–3. doi:10.3126/kumj.v10i4.10993. PMID 23575051.

- ↑ Gharaibeh, Almutez; Savage, Howard I; Scherer, Roberta W; Goldberg, Morton F; Lindsley, Kristina (2011). "Medical interventions for traumatic hyphema". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005431. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005431.pub2. PMC 3437611

. PMID 21249670.

. PMID 21249670. - ↑ "Tranexamic Acid use while Breastfeeding". www.drugs.com. 7 Nov 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Guerriero, Carla; Cairns, John; Perel, Pablo; Shakur, Haleema; Roberts, Ian; Crash 2 Trial, Collaborators (2011). "Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Administering Tranexamic Acid to Bleeding Trauma Patients Using Evidence from the CRASH-2 Trial". PLoS ONE. 6 (5): e18987. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618987G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018987. PMC 3086904

. PMID 21559279.

. PMID 21559279. - ↑ Tranexamic Acid to be available OtC

- ↑ In defence of multiple pharmacies

- ↑ Allen, Helen (June 13, 2012). "Tranexamic acid for bleeding". Patient UK.

External links

- CRASH-2: tranexamic acid and trauma patients

- Patient Experience with tranexamic acid

- Tranexamic acid, UK patient information leaflet