Triple Alliance (1882)

| Triple Alliance | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Military alliance | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

The Triple Alliance in 1913 | ||||||||||

| Capital | ||||||||||

| Political structure | Military alliance | |||||||||

| Historical era | Belle Époque | |||||||||

| • | Dual Alliance (Germany / Austria-Hungary) |

7 October 1879 | ||||||||

| • | Triple Alliance (Germany / Austria-Hungary / Italy) |

20 May 1882 | ||||||||

| • | Romania secretly joins | 18 October 1883 | ||||||||

| • | Dissolved | 28 June 1914 | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Events leading to World War I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

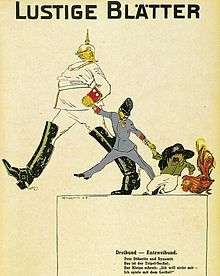

The Triple Alliance, also known as the Triplice was a secret agreement between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy formed on 20 May 1882 and renewed periodically until World War I. Germany and Austria-Hungary had been closely allied since 1879. Italy sought support against France shortly after it lost North African ambitions to the French. Each member promised mutual support in the event of an attack by any other great power. The treaty provided that Germany and Austria-Hungary were to assist Italy if it was attacked by France without provocation. In turn, Italy would assist Germany if attacked by France. In the event of a war between Austria-Hungary and Russia, Italy promised to remain neutral.

When the treaty was renewed in February 1887, Italy gained an empty promise of German support of Italian colonial ambitions in North Africa in return for Italy's continued friendship. Austria-Hungary had to be pressured by German chancellor Otto von Bismarck into accepting the principles of consultation and mutual agreement with Italy on any territorial changes initiated in the Balkans or on the coasts and islands of the Adriatic and Aegean seas. Italy and Austria-Hungary did not overcome their basic conflict of interest in that region despite the treaty. In 1891 attempts were made to join Britain to the Triplice, which, though unsuccessful, were widely believed to have succeeded in Russian diplomatic circles.[1]

Shortly after renewing the Alliance in June 1902, Italy secretly extended a similar guarantee to France.[2] By a particular agreement, neither Austria-Hungary nor Italy would change the status quo in the Balkans without previous consultation.[lower-alpha 1] On 1 November 1902, five months after the Triple Alliance was renewed, Italy reached an understanding with France that each would remain neutral in the event of an attack on the other.

When Austria-Hungary found itself at war in August 1914 with the rival Triple Entente, Italy proclaimed its neutrality, considering Austria-Hungary the aggressor and defaulting on the obligation to consult and agree compensations before changing the status quo in the Balkans, as agreed in 1912 renewal of the Triple Alliance.[4] Following parallel negotiation with both Triple Alliance, aimed to keep Italy neutral, and the Triple Entente, aimed to make Italy enter the conflict, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary. Carol I of Romania, through his Prime Minister Ion I. C. Brătianu, had also secretly pledged to support the Triple Alliance, but he remained neutral since Austria-Hungary started the war.[5][6]

Germany

The man chiefly responsible for the Triple Alliance was Otto von Bismarck, Chancellor of Germany. Bismarck wanted to prevent a war on two fronts, which is why he targeted these two countries specifically.[7]

Austria-Hungary

By the late 1870s, Austrian territorial ambitions in both the Italian peninsula and Central Europe had been thwarted by the rise of Italy and Germany as new national powers. With the decline and failed reforms of the Ottoman Empire, Slavic discontent in the occupied Balkans grew, and both Russia and Austria-Hungary saw an opportunity to expand in this region. In 1876, Russia offered to partition the Balkans, but Hungarian statesman Gyula Andrássy declined because Austria-Hungary was already a "saturated" state and it could not cope with additional territories.[8] The whole Empire was thus drawn into a new style of diplomatic brinkmanship, first conceived of by Andrássy, centering on the province of Bosnia and Herzegovina, a predominantly Slav area still under the control of the Ottoman Empire.

On the heels of the Great Balkan Crisis, Austro-Hungarian forces occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina in August 1878 and the empire eventually annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in October 1908 as a common holding under the control of the finance ministry, rather than attaching it to either Austria or Hungary. The occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina was a step taken in response to Russian advances into Bessarabia. Unable to mediate between Turkey and Russia over the control of Serbia, Austria–Hungary declared neutrality when the conflict between the two powers escalated into the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878).[8] In order to counter Russian and French interests in Europe, an alliance was concluded with Germany in October 1879 and with Italy in May 1882. World War I started in 1914.

Italy

The Kingdom of Italy, like some of the other European powers, wanted to set up colonies and build up an overseas empire. With this aim in mind, Italy joined the German–Austrian Alliance to form the Triple Alliance, partly in anger at the French seizure of Tunisia in 1881 (the so-called Schiaffo di Tunisi by Italian press), which many Italians had seen as a potential colony, and partly to guarantee herself support in case of foreign aggression: the main alliance compelled any signatory country to support the other parties if two other countries attacked. At the time, most European countries tried to ensure similar guarantees, and because of the Tunisian crisis Italy found no other big potential ally than its historical enemy, Austria-Hungary, against which Italy had fought three wars in the 34 years before the first treaty signing.

However, Italian public opinion remained unenthusiastic about their country's alignment with Austria-Hungary, a past enemy of Italian unification, and whose Italian populated districts in the Trentino and Istria were seen as occupied territories by Italian irredentists. In the years before World War I, many distinguished military analysts predicted that Italy would attack its supposed ally in the event of a large scale conflict. Italy's adherence to the Triple Alliance was doubted and from 1903 plans for a possible war against Rome were again maintained by the Austrian general staff.[9] Mutual suspicions led to reinforcement of the frontier and speculation in the press about a war between the two countries into the first decade of the twentieth century.[10] As late as 1911 Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, chief of the Austrian general staff, was advocating a military preemptive strike against Austria's supposed Italian ally.[11] This prediction was strengthened by Italy's invasion and annexation of Libya, bringing it into conflict with the German-backed Ottoman Empire.

Romania

King Carol I of Romania was of German ancestry. That, coupled with his wish to turn Romania into a center of stability in South-Eastern Europe (as well as his fear of Russia and the issue of Bassarabia), led to Romania joining the Triple Alliance on 18 October 1883. The alliance was a secret. Only the King and a handful of senior Romanian politicians knew about it. Romania and Austria-Hungary pledged to help each other in the event of a Russian, Serbian or Bulgarian attack. There were, however, several disputes between the two countries, the most notable being the policy of Magyarization of Transylvania's Romanian population. Romania did eventually manage to achieve the status of Regional Power in the aftermath of the Balkan Wars and the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest, but less than a year later, World War I started and Romania, after a period of neutrality, in which both the Central Powers and the Allies tried persuading Romania to join their respective sides, eventually joined the Allies in 1916, after being promised Romanian-inhabited Austro-Hungarian lands. Romania's reason for not siding with the Triple Alliance when the war started was the same as Italy's: the Triple Alliance was a defensive alliance, but Germany and Austria-Hungary had taken the offensive.[12][13][14][15][16]

Notes

- ↑ "However, if, in the course of events, the maintenance of the status quo in the regions of the Balkans or of the Ottoman coasts and islands in the Adriatic and in the Aegean Sea should become impossible, and if, whether in consequence of the action of a third Power or otherwise, Austria-Hungary or Italy should find themselves under the necessity of modifying it by a temporary or permanent occupation on their part, this occupation shall take place only after a previous agreement between the two Powers, based upon the principle of a reciprocal compensation for every advantage, territorial or other, which each of them might obtain beyond the present status quo, and giving satisfaction to the interests and well founded claims of the two Parties."[3]

Citations

- ↑ George Frost Kennan (1984). The Fateful Alliance: France, Russia, and the Coming of the First World War. Manchester University Press. pp. 82–86. ISBN 978-0-7190-1707-0.

- ↑ Charles Seymour (1916). The Diplomatic Background of the War. Yale University Press. p. 35,147.

- ↑ Grenville, John; Wasserstein, Bernard, eds. (2013). The Major International Treaties of the Twentieth Century: A History and Guide with Texts. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 9780415141253. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ↑ (art. 7) https://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/Expanded_version_of_1912_(In_English)

- ↑ Hentea, Călin (2007). Brief Romanian Military History. Scarecrow Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780810858206. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques (30 January 2012). "Chapter Fourteen: War Aims and Neutrality". In Horne, John. A Companion to World War I. Blackwell Publishing. p. 208. ISBN 9781405123860. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ↑ "Triple Alliance". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- 1 2 "Austria:Constitutional experimentation, 1860–67". Encyclopedia Britannica. 15 November 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ↑ Rothenburg 1976, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Rothenburg 1976, p. 152.

- ↑ Rothenburg 1976, p. 163.

- ↑ Keith Hitchins, A Concise History of Romania, p. 149

- ↑ James Lyon, Serbia and the Balkan Front, 1914: The Outbreak of the Great War, Chapter 3

- ↑ Richard F. Hamilton,Holger H. Herwig, The Origins of World War I, p. 401

- ↑ Manfried Rauchensteiner, The First World War and the End of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1914-1918, p. 65

- ↑ Rebecca Haynes, Romanian Policy Towards Germany, 1936-40, p. 3

References

- Kann, Robert (1974). A History of the Habsburg Empire. University of California Press. pp. 470–472. ISBN 0520042069. LCCN 72097733.

- Rothenburg, Gunther E. (1976). The Army of Francis Joseph. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 124–125.

Further reading

- Margaret Macmillan, The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (2013) ch 8