Tug of war

|

Ireland 600 kg team in the European Championships 2009 | |

| Highest governing body | Tug of War International Federation |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | TOW |

| First played | Ancient |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Non-contact |

| Team members | Eight (or more) |

| Mixed gender | mix 4+4 and separate |

| Type | Team sport, outdoor/indoor |

| Equipment | Rope and boots |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | Part of the Summer Olympic programme from 1900 to 1920 |

Tug of war (also known as war of tug, tug o' war, tug war, rope war, rope pulling, tug rope or tugging war) is a sport that directly puts two teams against each other in a test of strength: teams pull on opposite ends of a rope, with the goal being to bring the rope a certain distance in one direction against the force of the opposing team's pull.

Terminology

The Oxford English Dictionary says that the phrase "tug of war" originally meant "the decisive contest; the real struggle or tussle; a severe contest for supremacy". Only in the 19th century was it used as a term for an athletic contest between two teams who haul at the opposite ends of a rope.[1]

Origin

The origins of tug of war are uncertain, but this sport was practised in ancient Egypt, Greece and China, where it was held in legend that the Sun and Moon played Tug of War over the light and darkness.

According to a Tang dynasty book, The Notes of Feng, tug of war, under the name "hook pulling" (牽鉤), was used by the military commander of the State of Chu during the Spring and Autumn period (8th century BC to 5th century BC) to train warriors. During the Tang dynasty, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang promoted large-scale tug of war games, using ropes of up to 167 metres (548 ft) with shorter ropes attached, and more than 500 people on each end of the rope. Each side also had its own team of drummers to encourage the participants.[3]

In ancient Greece the sport was called helkustinda (Greek: ἑλκυστίνδα), efelkustinda (ἐφελκυστίνδα) and dielkustinda (διελκυστίνδα),[4] which derives from dielkō (διέλκω), meaning amongst others "I pull through",[5] all deriving from the verb helkō (ἕλκω), "I draw, I pull".[6] Helkustinda and efelkustinda seem to have been ordinary versions of tug of war, while dielkustinda had no rope, according to Julius Pollux.[7] It is possible that the teams held hands when pulling, which would have increased difficulty, since handgrips are more difficult to sustain than a grip of a rope. Tug of war games in ancient Greece were among the most popular games used for strength and would help build strength needed for battle in full armor.[8]

Archeological evidence shows that tug of war was also popular in India in the 12th century:

There is no specific time and place in history to define the origin of the game of Tug of War. The contest of pulling on the rope originates from ancient ceremonies and rituals. Evidence is found in countries like Egypt, India, Myanmar, New Guinea... The origin of the game in India has strong archaeological roots going back at least to the 12th century AD in the area what is today the State of Orissa on the east coast. The famous Sun Temple of Konark has a stone relief on the west wing of the structure clearly showing the game of Tug of War in progress.[9]

Tug of war stories about heroic champions from Scandinavia and Germany circulate Western Europe where Viking warriors pull on animal skins over open pits of fire in tests of strength and endurance, in preparation for battle and plunder.

1500 and 1600 – tug of war is popularised during tournaments in French châteaux gardens and later in Great Britain

1800 – tug of war begins a new tradition among seafaring men who were required to tug on lines to adjust sails while ships were under way and even in battle.[10]

The Mohave people occasionally used tug-of-war matches as means of settling disputes.[11]

As a sport

There are tug of war clubs in many countries, and both men and women participate.

The sport was part of the Olympic Games from 1900 until 1920, but has not been included since. The sport is part of the World Games. The Tug of War International Federation (TWIF), organises World Championships for nation teams biannually, for both indoor and outdoor contests, and a similar competition for club teams.

In England the sport is catered for by the Tug of War Association (formed in 1958), and the Tug of War Federation of Great Britain (formed in 1984). In Scotland, the Scottish Tug of War Association was formed in 1980. The sport also features in Highland Games there.

Between 1976 and 1988 Tug of War was a regular event during the television series Battle of the Network Stars. Teams of celebrities representing each major network competed in different sporting events culminating into the final event, the Tug of War. Lou Ferrigno's epic tug-o'-war performance in May 1979 is considered the greatest feat in 'Battle' history.

National organizations

The sport is played almost in every country in the world. However, a small selection of countries have set up a national body to govern the sport. Most of these national bodies are associated then with the International governing body call TWIF which stands for The Tug of War International Federation. As of 2008 there are 53 countries associated with TWIF, among which are Scotland, Ireland, England, India, Switzerland, Belgium, Italy[12] and the United States.

Regional variations

- In the Basque Country, this sport is considered a popular rural sport, with many associations and clubs. In Basque, it is called Sokatira.

- Each Fourth of July, two California towns separated by an ocean channel Stinson Beach, California and Bolinas, California gather to compete in an annual tug-of-war.[13][14]

- A special edition of the Superstars television series, called "The Superteams", features a tug-of-war, usually as the final event.

- The Battle of the Network Stars featured a tug-of-war as one of its many events.

- The Peruvian children's series Nubeluz featured its own version of tug-of-war (called La Fuerza Glufica), where each team battled 3-on-3 on platforms suspended over a pool of water in an effort to pull the other team into the pool.

- A game of tug-of-war, on tilted platforms, was used on the US, UK and Australian versions of the Gladiators television series, although the game was played with two sole opposing participants.

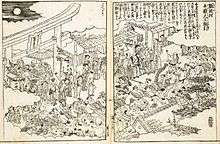

- In Japan, the tug of war (綱引き/Tsunahiki in Japanese) is a staple of school sports festivals. The tug-of-war is also a traditional way to pray for a plentiful harvest throughout Japan and it is a popular ritual around the country. The Kariwano Tug-of-war in Daisen, Akita, is said to be more than 500 years old, and is a national folklore cultural asset.[15] The Underwater Tug-of-War Festival in Mihama, Fukui is 380 years old, and takes place in every January.[16] The Sendai Great Tug of War in Satsumasendai, Kagoshima is known as Kenka-zuna or "brawl tug".[17] Around 3,000 men pull a huge rope which is 365 metres (1,198 ft) long. The event is said to have been started by feudal warlord Yoshihiro Shimadzu, with the aim of boosting the morale of his soldiers before the decisive Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. Nanba Hachiman Jinja's tug-of-war, which started in the Edo period, is Osaka's folklore cultural asset.[18] The Naha Tug-of-war in Okinawa is also famous.

- In Indonesia, Tarik Tambang is a popular sport held in many events, such as the Indonesian Independence Day celebration, school events, and scout events. The rope used is called dadung, made from fibers of lar between two jousters. Two cinder blocks are placed a distance apart and the two jousters stand upon the blocks with a rope stretched between them. The objective for each jouster is to either a) cause their opponent to fall off their block, or b) to take their opponent's end of the rope from them.[19]

- A form of tug-of-war, called juldarigi, is an important part of many agricultural festivals in Korea.

Formal rules

Two teams of eight, whose total mass must not exceed a maximum weight as determined for the class, align themselves at the end of a rope approximately 11 centimetres (4.3 in) in circumference. The rope is marked with a "centre line" and two markings 4 metres (13 ft) either side of the centre line. The teams start with the rope's centre line directly above a line marked on the ground, and once the contest (the "pull") has commenced, attempt to pull the other team such that the marking on the rope closest to their opponent crosses the centre line, or the opponents commit a foul (such as a team member sitting or falling down).

Lowering ones elbow below the knee during a 'pull' - known as 'Locking' - is a foul, as is touching the ground for extended periods of time. The rope must go under the arms; actions such as pulling the rope over the shoulders may be considered a foul. These rules apply in highly organized competitions such as the World Championships. However, in small or informal entertainment competitions, the rules are often arbitrarily interpreted and followed.

A contest may feature a moat in a neutral zone, usually of mud or softened ground, which eliminates players who cross the zone or fall into it.

Tactics

Aside from the raw muscle power needed for tug of war, it is also a technical sport. The cooperation or "rhythm" of team members play an equally important role in victory, if not more, than their physical strength. To achieve this, a person called a "driver" is used to harmonize the team's joint traction power. He moves up and down next to his team pulling on the rope, giving orders to them when to pull and when to rest (called "hanging"). If he spots the opponents trying to pull his team away, he gives a "hang" command, each member will dig into the grass with his/her boots and movement of the rope is limited. When the opponents are played out, he shouts "pull" and rhythmically waves his hat or handkerchief for his team to pull together. Slowly but surely, the other team is forced into surrender by a runaway pull. Another factor that affects the game that is little known are the players' weights. The heavier someone is, the more static friction their feet have to the ground, and if there isn't enough friction and they weigh too little, even if he/she is pulling extremely hard, the force won't go into the rope. Their feet will simply slide along the ground if their opponent(s) have better static friction with the ground. In general, as long as one team has enough static friction and can pull hard enough to overcome the static friction of their opponent(s), that team can easily win the match.

Injury risks

In addition to injuries from falling and from back strains (some of which may be serious), catastrophic injuries may occur, such as finger, hand, or even arm amputations. Amputations or avulsions may result from two causes: looping or wrapping the rope around a hand or wrist, and impact from elastic recoil if the rope breaks. Amateur organizers of tugs of war may underestimate the forces generated, or overestimate the breaking strength of common ropes, and may thus be unaware of the possible consequences if a rope snaps under extreme tension. The broken ends of a rope made with a somewhat elastic polymer such as common nylon can reach high speeds, and can easily sever fingers. For this reason, specially engineered tug of war ropes exist that can safely withstand the forces generated.[20]

Notable incidents

| Date | Location | Rope snapped | # Death | # Severely Injured | # Overall Injured | # Total Participants | Death Cause/ Injury Details | Rope Details | Other Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 June 1995[21] | Westernohe, Germany | 2 | 5 | 29 | 650 | Crushed and hit ground hard | "Thumb-thick" nylon | Scouts attempt Guinness Book of Records entry | |

| 25 October 1997[22][23][24][25] | Taipei, Taiwan | 0 | 2 | 42 | 1500 | Arms severed below shoulder | 5-centimetre (2.0 in) nylon, max. strength 26,000 kilograms (57,000 lb) | Official event, with foreign dignitaries | |

| 4 February 2013[26] | El Monte California | 0 | 2 | 2 | ? | Fingers severed | Unknown | Lunchtime high school activity |

Notes

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary

- ↑ The bas-relief of the Churning of the Sea of Milk shows Vishnu in the centre, his turtle avatar Kurma below, asuras and devas to left and right, and apsaras and Indra above.

- ↑ Tang dynasty Feng Yan: Notes of Feng, volume 6

- ↑ διελκυστίνδα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ διέλκω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ ἕλκω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ Pollux, 9.112

- ↑ Jaime Marie Layne, The Enculturative Function of Toys and Games in Ancient Greece and Rome, ProQuest, UMI Dissertation Publishing, 2011

- ↑ Tug of War Federation of India: History

- ↑ Equity Gaming: History of Tug of War

- ↑ , Page 133.

- ↑ http://www.figest.it/

- ↑ Uniquely West Marin: Fourth of July Tug of War | Point Reyes Weekend

- ↑ /http://www.marinij.com/marin/ci_4013474

- ↑ Kariwano Ootsunahiki NHK

- ↑ Underwater Tug-of-War Festival in Mihama Fukui Shimbun, 2013/01/20

- ↑ SENDAI GREAT TUG-of WAR (Sendai Otsunahiki / 川内大綱引き) Kagoshima Internationalization Council.

- ↑ Tsunahiki shinji(shinto ritual) Nanba Hachiman Jinja, 2015/01/18

- ↑ Mary Hirt, Irene Ramos (2008), "Rope Jousting", Maximum Middle School Physical Education, p. 144, ISBN 978-0-7360-5779-0

- ↑ 2015

- ↑ 2 Boy Scouts Die When Tug-Of-War Rope Snaps

- ↑ Two Men Lose Arms in tug-of-war, The Nation, October 27, 1997 (available at Google.news).

- ↑ Tug-of-war: accident leaves arms hanging and mayor apologetic (China Times Tue, Oct 28, 1997 edition (available at Chinainformed.com).

- ↑ Taiwanese doctors reattach arms ripped off in tug-of-war, Boca Raton News, October 27, 1997, Page 7A, (available as new

- ↑ Disarmed - Disarmanent at Snopes.com.

- ↑ "Teens recovering after losing fingers during tug-of-war match". Associated Press. February 5, 2013. Archived from the original on February 7, 2013.

Bibliography

- Henning Eichberg, "Pull and tug: Towards a philosophy of the playing 'You'", in: Bodily Democracy: Towards a Philosophy of Sport for All, London: Routledge 2010, pp. 180–199.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tug of war. |

- Tug of War International Federation

- The Tug of War Association (England)

- Tug of War (Sports123.com, via Wayback Machine, Internet Archive): list of winners in the main championships