Unix philosophy

The Unix philosophy, originated by Ken Thompson, is a set of cultural norms and philosophical approaches to minimalist, modular software development. It is based on the experience of leading developers of the Unix operating system. Early Unix developers were important in bringing the concepts of modularity and reusability into software engineering practice, spawning a "software tools" movement. Over time, the leading developers of Unix (and programs that ran on it) established a set of cultural norms for developing software, norms which became as important and influential as the technology of Unix itself; this has been termed the "Unix philosophy."

The Unix philosophy emphasizes building simple, short, clear, modular, and extensible code that can be easily maintained and repurposed by developers other than its creators. The Unix philosophy favors composability as opposed to monolithic design.

Origin

The UNIX philosophy is documented by Doug McIlroy[1] in the The Bell System Technical Journal from 1978:[2]

- Make each program do one thing well. To do a new job, build afresh rather than complicate old programs by adding new "features".

- Expect the output of every program to become the input to another, as yet unknown, program. Don't clutter output with extraneous information. Avoid stringently columnar or binary input formats. Don't insist on interactive input.

- Design and build software, even operating systems, to be tried early, ideally within weeks. Don't hesitate to throw away the clumsy parts and rebuild them.

- Use tools in preference to unskilled help to lighten a programming task, even if you have to detour to build the tools and expect to throw some of them out after you've finished using them.

Later summarized by Peter H. Salus in A Quarter-Century of Unix (1994):[1] This is the Unix philosophy:

- Write programs that do one thing and do it well.

- Write programs to work together.

- Write programs to handle text streams, because that is a universal interface.

In the book The Pragmatic Programmer: From Journeyman to Master the authors mention the philosophy of combining "small, sharp tools" and the use of "common underlying format—the line-oriented, plain text file"[3] to accomplish larger tasks.

The whole philosophy of UNIX seems to stay out of assembler.

The development of pipes in 1973 formalized the existing principle of stdin-stdout into a philosophy in Version 3 Unix, with older software rewritten to comply. Previously visible in early utilities such as wc, cat, and uniq, McIlroy cites Thompson's grep as what "ingrained the tools outlook irrevocably" in the operating system, with later tools like tr, m4, and sed imitating how grep transforms the input stream.[5]

"The truth about Unix: The user interface is horrid"[6] was a 1981 criticism of the design philosophy published in Datamation. It was written by Don Norman, who had a background in cognitive science and was the key proponent of the then-current philosophy of cognitive engineering,[4] apparently focused on how engineers comprehend and form a personal cognitive model of a system.

The UNIX Programming Environment

In their preface to the 1984 book, The UNIX Programming Environment, Brian Kernighan and Rob Pike, both from Bell Labs, give a brief description of the Unix design and the Unix philosophy:[7]

Even though the UNIX system introduces a number of innovative programs and techniques, no single program or idea makes it work well. Instead, what makes it effective is the approach to programming, a philosophy of using the computer. Although that philosophy can't be written down in a single sentence, at its heart is the idea that the power of a system comes more from the relationships among programs than from the programs themselves. Many UNIX programs do quite trivial things in isolation, but, combined with other programs, become general and useful tools.

The authors further write that their goal for this book is "to communicate the UNIX programming philosophy."[7]

Program Design in the UNIX Environment

In October 1984, Brian Kernighan and Rob Pike published a paper called Program Design in the UNIX Environment. In this paper, they criticize the accretion of program options and features found in some newer Unix systems such as 4.2BSD and System V, and explain the Unix philosophy of software tools, each performing one general function:[8]

Much of the power of the UNIX operating system comes from a style of program design that makes programs easy to use and, more important, easy to combine with other programs. This style has been called the use of software tools, and depends more on how the programs fit into the programming environment and how they can be used with other programs than on how they are designed internally. [...] This style was based on the use of tools: using programs separately or in combination to get a job done, rather than doing it by hand, by monolithic self-sufficient subsystems, or by special-purpose, one-time programs.

The authors contrast Unix tools such as cat, with larger program suites used by other systems.[8]

The design of cat is typical of most UNIX programs: it implements one simple but general function that can be used in many different applications (including many not envisioned by the original author). Other commands are used for other functions. For example, there are separate commands for file system tasks like renaming files, deleting them, or telling how big they are. Other systems instead lump these into a single "file system" command with an internal structure and command language of its own. (The PIP file copy program found on operating systems like CP/M or RSX-11 is an example.) That approach is not necessarily worse or better, but it is certainly against the UNIX philosophy.

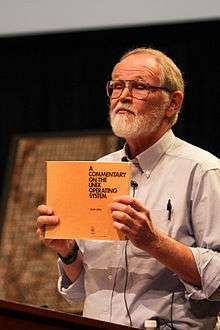

Doug McIlroy on Unix programming

_Receiving_Japan_Prize.jpeg)

McIlroy, then head of the Bell Labs CSRC (Computing Sciences Research Center), and inventor of the Unix pipe,[9] summarized the Unix philosophy as follows:[1]

This is the Unix philosophy: Write programs that do one thing and do it well. Write programs to work together. Write programs to handle text streams, because that is a universal interface.

Beyond these statements, he has also emphasized simplicity and minimalism in Unix programming:[1]

The notion of "intricate and beautiful complexities" is almost an oxymoron. Unix programmers vie with each other for "simple and beautiful" honors — a point that's implicit in these rules, but is well worth making overt.

Conversely, McIlroy has criticized modern Linux as having software bloat, remarking that, "adoring admirers have fed Linux goodies into a disheartening state of obesity."[10] He contrasts this with earlier approach taken at Bell Labs when developing and revising Research Unix:[11]

Everything was small... and my heart sinks for Linux when I see the size of it. [...] The manual page, which really used to be a manual page, is now a small volume, with a thousand options... We used to sit around in the Unix Room saying, 'What can we throw out? Why is there this option?' It's often because there is some deficiency in the basic design — you didn't really hit the right design point. Instead of adding an option, think about what was forcing you to add that option.

Do One Thing and Do It Well

As stated by McIlroy, and generally accepted throughout the Unix community, Unix programs have always been expected to follow the concept of DOTADIW, or "Do One Thing and Do It Well." Sources for the acronym DOTADIW are limited throughout the internet, but is discussed at length during the development and packaging of new operating systems, especially in the Linux community. There has been a point of great contention during the Linux systemd debates of 2014–2015, and especially in the Debian community.[12]

Patrick Volkerding, the project lead of Slackware Linux, invoked this design principle in a criticism of the systemd architecture, stating that, "attempting to control services, sockets, devices, mounts, etc., all within one daemon flies in the face of the UNIX concept of doing one thing and doing it well."[13]

Eric Raymond’s 17 Unix Rules

In his book The Art of Unix Programming that was first published in 2003,[14] Eric S. Raymond, an American programmer and open source advocate, summarizes the Unix philosophy as KISS Principle of "Keep it Simple, Stupid."[15] He provides a series of design rules:[1]

- Rule of Modularity

- Developers should build a program out of simple parts connected by well defined interfaces, so problems are local, and parts of the program can be replaced in future versions to support new features. This rule aims to save time on debugging code that is complex, long, and unreadable.

- Rule of Clarity

- Developers should write programs as if the most important communication is to the developer, including themselves, who will read and maintain the program rather than the computer. This rule aims to make code readable and comprehensible for whoever works on the code in future.

- Rule of Composition

- Developers should write programs that can communicate easily with other programs. This rule aims to allow developers to break down projects into small, simple programs rather than overly complex monolithic programs.

- Rule of Separation

- Developers should separate the mechanisms of the programs from the policies of the programs; one method is to divide a program into a front-end interface and a back-end engine with which that interface communicates. This rule aims to prevent bug introduction by allowing policies to be changed with minimum likelihood of destabilizing operational mechanisms.

- Rule of Simplicity

- Developers should design for simplicity by looking for ways to break up program systems into small, straightforward cooperating pieces. This rule aims to discourage developers’ affection for writing “intricate and beautiful complexities” that are in reality bug prone programs.

- Rule of Parsimony

- Developers should avoid writing big programs. This rule aims to prevent overinvestment of development time in failed or suboptimal approaches caused by the owners of the program’s reluctance to throw away visibly large pieces of work. Smaller programs are not only easier to optimize and maintain; they are easier to delete when deprecated.

- Rule of Transparency

- Developers should design for visibility and discoverability by writing in a way that their thought process can lucidly be seen by future developers working on the project and using input and output formats that make it easy to identify valid input and correct output. This rule aims to reduce debugging time and extend the lifespan of programs.

- Rule of Robustness

- Developers should design robust programs by designing for transparency and discoverability, because code that is easy to understand is easier to stress test for unexpected conditions that may not be foreseeable in complex programs. This rule aims to help developers build robust, reliable products.

- Rule of Representation

- Developers should choose to make data more complicated rather than the procedural logic of the program when faced with the choice, because it is easier for humans to understand complex data compared with complex logic. This rule aims to make programs more readable for any developer working on the project, which allows the program to be maintained.

- Rule of Least Surprise

- Developers should design programs that build on top of the potential users' expected knowledge; for example, ‘+’ in a calculator program should always mean 'addition'. This rule aims to encourage developers to build intuitive products that are easy to use.

- Rule of Silence

- Developers should design programs so that they do not print unnecessary output. This rule aims to allow other programs and developers to pick out the information they need from a program's output without having to parse verbosity.

- Rule of Repair

- Developers should design programs that fail in a manner that is easy to localize and diagnose or in other words “fail noisily”. This rule aims to prevent incorrect output from a program from becoming an input and corrupting the output of other code undetected.

- Rule of Economy

- Developers should value developer time over machine time, because machine cycles today are relatively inexpensive compared to prices in the 1970s. This rule aims to reduce development costs of projects.

- Rule of Generation

- Developers should avoid writing code by hand and instead write abstract high-level programs that generate code. This rule aims to reduce human errors and save time.

- Rule of Optimization

- Developers should prototype software before polishing it. This rule aims to prevent developers from spending too much time for marginal gains.

- Rule of Diversity

- Developers should design their programs to be flexible and open. This rule aims to make programs flexible, allowing them to be used in ways other than those their developers intended.

- Rule of Extensibility

- Developers should design for the future by making their protocols extensible, allowing for easy plugins without modification to the program's architecture by other developers, noting the version of the program, and more. This rule aims to extend the lifespan and enhance the utility of the code the developer writes.

Mike Gancarz: The UNIX Philosophy

In 1994, Mike Gancarz (a member of the team that designed the X Window System), drew on his own experience with Unix, as well as discussions with fellow programmers and people in other fields who depended on Unix, to produce The UNIX Philosophy which sums it up in 9 paramount precepts:

- Small is beautiful.

- Make each program do one thing well.

- Build a prototype as soon as possible.

- Choose portability over efficiency.

- Store data in flat text files.

- Use software leverage to your advantage.

- Use shell scripts to increase leverage and portability.

- Avoid captive user interfaces.

- Make every program a filter.

"Worse is better"

Richard P. Gabriel suggests that a key advantage of Unix was that it embodied a design philosophy he termed "worse is better", in which simplicity of both the interface and the implementation are more important than any other attributes of the system—including correctness, consistency, and completeness. Gabriel argues that this design style has key evolutionary advantages, though he questions the quality of some results.

For example, in the early days Unix used a monolithic kernel (which means that user processes carried out kernel system calls all on the user stack). If a signal was delivered to a process while it was blocked on a long-term I/O in the kernel, then what should be done? Should the signal be delayed, possibly for a long time (maybe indefinitely) while the I/O completed? The signal handler could not be executed when the process was in kernel mode, with sensitive kernel data on the stack. Should the kernel back-out the system call, and store it, for replay and restart later, assuming that the signal handler completes successfully?

In these cases Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie favored simplicity over perfection. The Unix system would occasionally return early from a system call with an error stating that it had done nothing—the "Interrupted System Call", or an error number 4 (EINTR) in today's systems. Of course the call had been aborted in order to call the signal handler. This could only happen for a handful of long-running system calls such as read(), write(), open(), and select(). On the plus side, this made the I/O system many times simpler to design and understand. The vast majority of user programs were never affected because they didn't handle or experience signals other than SIGINT and would die right away if one was raised. For the few other programs—things like shells or text editors that respond to job control key presses—small wrappers could be added to system calls so as to retry the call right away if this EINTR error was raised. Thus, the problem was solved in a simple manner.

See also

- Cognitive engineering

- Unix architecture

- Minimalism (computing)

- Plan 9 from Bell Labs

- Pipes and filters

- Standard streams

- The Unix-Haters Handbook

- Software engineering

- Hacker (programmer subculture)

- Hacker ethic

- List of software development philosophies

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Raymond, Eric S. (2003-09-23). "Basics of the Unix Philosophy". The Art of Unix Programming. Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 0-13-142901-9. Retrieved 2016-11-01.

- ↑ Doug McIlroy, E. N. Pinson, B. A. Tague (8 July 1978). "Unix Time-Sharing System Forward". The Bell System Technical Journal. Bell Laboratories. pp. 1902–1903.

- ↑ Andrew Hunt; David Thomas (1999). "The Pragmatic Programmer: From Journeyman to Master".

- 1 2 "Joseph H. Condon". Princeton University History of Science.

- ↑ McIlroy, M. D. (1987). A Research Unix reader: annotated excerpts from the Programmer's Manual, 1971–1986 (PDF) (Technical report). CSTR. Bell Labs. 139.

- ↑ Norman, Don (1981). "The truth about Unix: The user interface is horrid" (PDF). Datamation (27(12)).

- 1 2 Kernighan, Brian W. Pike, Rob. The UNIX Programming Environment. 1984. viii

- 1 2 Rob Pike; Brian W. Kernighan (October 1984). "Program Design in the UNIX Environment" (PDF).

- ↑ http://cm.bell-labs.com/cm/cs/who/dmr/mdmpipe.html

- ↑ Douglas McIlroy. "Remarks for Japan Prize award ceremony for Dennis Ritchie, May 19, 2011, Murray Hill, NJ" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- ↑ Bill McGonigle. "Ancestry of Linux — How the Fun Began (2005)". Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- ↑ Varghese, Sam. "Systemd fallout: Two Debian technical panel members resign". ITWire. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- ↑ "Interview with Patrick Volkerding of Slackware". linuxquestions.org. 2012-06-07. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ↑ Raymond, Eric (2003-09-19). The Art of Unix Programming. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-13-142901-9. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ↑ Raymond, Eric (2003-09-19). "The Unix Philosophy in One Lesson". The Art of Unix Programming. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-13-142901-9. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

References

- The Unix Programming Environment by Brian Kernighan and Rob Pike, 1984

- Program Design in the UNIX Environment – The paper by Pike and Kernighan that preceded the book.

- Notes on Programming in C, Rob Pike, September 21, 1989

- A Quarter Century of Unix, Peter H. Salus, Addison-Wesley, May 31, 1994 (ISBN 0-201-54777-5)

- Philosophy — from The Art of Unix Programming, Eric S. Raymond, Addison-Wesley, September 17, 2003 (ISBN 0-13-142901-9)

- Final Report of the Multics Kernel Design Project by M. D. Schroeder, D. D. Clark, J. H. Saltzer, and D. H. Wells, 1977.

- The UNIX Philosophy, Mike Gancarz, ISBN 1-55558-123-4

External links

- Basics of the Unix Philosophy – by Catb.org

- The Unix Philosophy: A Brief Introduction – by The Linux Information Project (LINFO)

- The Unix Philosophy

- Why the Unix Philosophy still matters