Upper Egypt

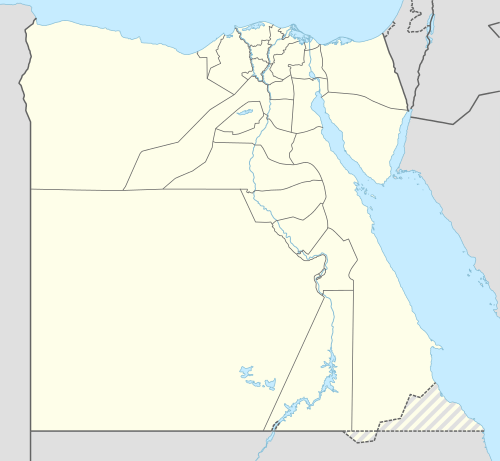

Upper Egypt (Arabic: صعيد مصر Saʿīd Miṣr, shortened to الصعيد El Ṣeʿīd; pronounced [esˤːe.ˈʕiːd], Coptic: ⲙⲁⲣⲏⲥ) is the strip of land on both sides of the Nile that extends between Nubia and downriver (northwards) to Lower Egypt.

Geography

Upper Egypt is between the Cataracts of the Nile above modern-day Aswan, downriver (northwards) to the area between Dahshur and El-Ayait, which is south of modern-day Cairo. The northern (downriver) part of Upper Egypt, between Sohag and El-Ayait, is also known as Middle Egypt.

In Arabic, inhabitants of Upper Egypt are known as Sa'idis and they generally speak Sa'idi Arabic.

In ancient Egypt, Upper Egypt was known as tꜣ šmꜣw,[1] literally "the Land of Reeds" or "the Sedgeland"[2] It was divided into twenty-two districts called nomes.[3] The first nome was roughly where modern-day Aswan is and the twenty-second was at modern Atfih just to the south of Cairo.

History

Predynastic Egypt

The main city of prehistoric Upper Egypt was Nekhen,[4] whose patron deity was the vulture goddess Nekhbet.[5]

By about 3600 BC, Neolithic Egyptian societies along the Nile had based their culture on the raising of crops and the domestication of animals.[6] Shortly after 3600 BC, Egyptian society began to grow and increase in complexity.[7] A new and distinctive pottery, which was related to the Levantine ceramics, appeared during this time. Extensive use of copper became common during this time.[7] The Mesopotamian process of sun-drying adobe and architectural principles—including the use of the arch and recessed walls for decorative effect—became popular during this time.[7]

Concurrent with these cultural advances, a process of unification of the societies and towns of the upper Nile River, or Upper Egypt, occurred. At the same time the societies of the Nile Delta, or Lower Egypt also underwent a unification process.[7] Warfare between Upper and Lower Egypt occurred often.[7] During his reign in Upper Egypt, King Narmer defeated his enemies on the Delta and merged both the Kingdom of Upper and Lower Egypt under his single rule.[8]

Dynastic Egypt

For most of pharaonic Egypt's history, Thebes was the administrative center of Upper Egypt. After its devastation by the Assyrians, its importance declined. Under the Ptolemies, Ptolemais Hermiou took over the role of Upper Egypt's capital city.[9] Upper Egypt was represented by the tall White Crown Hedjet, and its symbols were the flowering lotus and the sedge.

Medieval Egypt

In the 11th century, large numbers of pastoralists, known as Hilalians, fled Upper Egypt and moved westward into Libya and as far as Tunis.[10] It is believed that degraded grazing conditions in Upper Egypt, associated with the beginning of the Medieval Warm Period, were the root cause of the migration.[11]

20th-century Egypt

In the 20th-century Egypt, the title Prince of the Sa'id (meaning Prince of Upper Egypt) was used by the heir apparent to the Egyptian throne.[Note 1]

Although the Kingdom of Egypt was abolished after the Egyptian revolution of 1952, the title continues to be used by Muhammad Ali, Prince of the Sa'id.

List of rulers of prehistoric Upper Egypt

The following list may not be complete (there are many more of uncertain existence):

| Name | Image | Comments | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elephant | End of 4th millennium BC | ||

| Bull | 4th millennium BC | ||

| Scorpion I | Oldest tomb at Umm el-Qa'ab had scorpion insignia | c. 3200 BC? | |

| Iry-Hor |  |

Possibly the immediate predecessor of Ka. | c. 3150 BC? |

| Ka[13][14] | |

May be read Sekhen rather than Ka. Possibly the immediate predecessor of Narmer. | c. 3100 BC |

| Scorpion II |  |

Potentially read Serqet; possibly the same person as Narmer. | c. 3150 BC |

| Narmer |  |

The king who combined Upper and Lower Egypt.[15] | c. 3150 BC |

List of nomes

| Number | Egyptian Name | Capital | Modern Capital | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ta-Seti | Abu / Yebu (Elephantine) | Aswan | Land of the Bow |

| 2 | Wetjes-Hor | Djeba (Apollonopolis Magna) | Edfu | Throne of Horus |

| 3 | Nekhen | Nekhen (Hierakon polis) | al-Kab | Shrine |

| 4 | Waset | Niwt-rst / Waset (Thebes) | Karnak | Sceptre |

| 5 | Harawî | Gebtu (Coptos) | Qift | Two Falcons |

| 6 | Aa-ta | Iunet / Tantere (Tentyra) | Dendera | Crocodile |

| 7 | Seshesh | Seshesh (Diospolis Parva) | Hu | Sistrum |

| 8 | Abdju | Abdju (Abydos) | al-Birba | Great Land |

| 9 | Min | Apu / Khen-min (Panopolis) | Akhmim | Min |

| 10 | Wadjet | Djew-qa / Tjebu (Aphroditopolis) | Edfu | Cobra |

| 11 | Set | Shashotep (Hypselis) | Shutb | Set animal |

| 12 | Tu-ph | Hut-Sekhem-Senusret (Antaeopolis) | Qaw al-Kebir | Viper Mountain |

| 13 | Atef-Khent | z3wj-tj (Lycopolis) | Asyut | Upper Sycamore and Viper |

| 14 | Atef-Pehu | Qesy (Cusae) | al-Qusiya | Lower Sycamore and Viper |

| 15 | Wenet | Khemenu (Hermopolis) | Hermopolis | Hare[16] |

| 16 | Ma-hedj | Herwer? | Hur? | Oryx[16] |

| 17 | Anpu | Saka (Cynopolis) | al-Kais | Anubis |

| 18 | Sep | Teudjoi / Hutnesut (Alabastronopolis) | el-Hiba | Set |

| 19 | Uab | Per-Medjed (Oxyrhynchus) | el-Bahnasa | Two Sceptres |

| 20 | Atef-Khent | Henen-nesut (Heracleopolis Magna) | Ihnasiyyah al-Madinah | Southern Sycamore |

| 21 | Atef-Pehu | Shenakhen / Semenuhor (Crocodilopolis, Arsinoë) | Faiyum | Northern Sycamore |

| 22 | Maten | Tepihu (Aphroditopolis) | Atfih | Knife |

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

See also

Further reading

- Edel, Elmar (1961) Zu den Inschriften auf den Jahreszeitenreliefs der "Weltkammer" aus dem Sonnenheiligtum des Niuserre Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, OCLC 309958651, in German.

Notes

- ↑ The title was first used by Prince Farouk, the son and heir of King Fouad I. Prince Farouk was officially named Prince of the Sa'id on 12 December 1933.[12]

References

- ↑ Ermann & Grapow 1982, Wb 5, 227.4-14.

- ↑ Ermann & Grapow (1982), Wb 4, 477.9-11

- ↑ The Encyclopedia Americana Grolier Incorporated, 1988, p.34

- ↑ Bard & Shubert (1999), p. 371

- ↑ David (1975), p. 149

- ↑ Roebuck (1966), p. 51

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roebuck (1966), pp. 52–53

- ↑ Roebuck (1966), p. 53

- ↑ Chauveau (2000), p. 68

- ↑ Ballais (2000), p. 133

- ↑ Ballais (2000), p. 134

- ↑ Brice (1981), p. 299

- ↑ Rice 1999, p. 86.

- ↑ Wilkinson 1999, p. 57f.

- ↑ Shaw 2000, p. 196.

- 1 2 Grajetzki (2006), pp. 109–111

Bibliography

- Ballais, Jean-Louis (2000). "Conquests and land degradation in the eastern Maghreb". In Graeme Barker & David Gilbertson. Sahara and Sahel. The Archaeology of Drylands: Living at the Margin. Vol. 1, Part III. London: Routledge. pp. 125–136. ISBN 978-0-415-23001-8.

- Bard, Katheryn A.; Shubert, Steven Blake (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18589-0.

- Brice, William Charles (1981). An Historical Atlas of Islam. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-06116-9. OCLC 9194288.

- Chauveau, Michel (2000). Egypt in the Age of Cleopatra: History and Society Under the Ptolemies. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3597-8.

- David, Ann Rosalie (1975). The Egyptian Kingdoms. London: Elsevier Phaidon. OCLC 2122106.

- Ermann, Johann Peter Adolf; Grapow, Hermann (1982). Wörterbuch der Ägyptischen Sprache [Dictionary of the Egyptian Language] (in German). Berlin: Akademie. ISBN 3-05-002263-9.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2006). The Middle Kingdom of ancient Egypt: History, Archaeology and Society. London: Duckworth Egyptology. ISBN 978-0-7156-3435-6.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15449-9.

- Roebuck, Carl (1966). The World of Ancient Times. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons Publishing.

- Shaw, Ian (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999). Early Dynastic Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18633-1.

External links

Media related to Upper Egypt at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Upper Egypt at Wikimedia Commons