Vertigo (wordless novel)

_Vertigo_-_rain_at_fair.jpg)

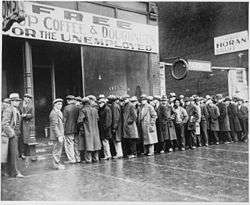

Vertigo is a wordless novel by American artist Lynd Ward (1905–1985), published in 1937. In three intertwining parts, the story tells of the effects the Great Depression has on the lives of an elderly industrialist and a young man and woman. Considered his masterpiece, Ward uses the work to express the socialist sympathies of his upbringing; he aimed to present what he called "impersonal social forces" by depicting the individuals whose actions are responsible for those forces.

The work is filled with symbolic motifs, and is in a more detailed and realistic style than Ward's Expressionistic earlier works. The images—one to a page—are borderless and of varied dimensions. At 230 wood engravings Vertigo was Ward's longest and most complex wordless novel, and proved to be the last he finished—in 1940 he abandoned one he was working on, and in the last years of his life began another that he never finished. For the remainder of his career Ward turned to book illustration, especially children's books, some of which he or his wife May McNeer authored.

Synopsis

The story takes place from 1929 to 1935 and follows three main characters: a young woman, a young man, and an elderly man. Each is the focus of a section of the book,[1] which is in three parts: "The Girl", broken into subsections labeled by years; "An Elderly Gentleman", whose subsections are in months; and "The Boy", subdivided into days.[2]

In "The Girl", a musically-gifted young woman with an optimistic future finds and gets engaged to a young man. As the Great Depression deepens, her lover moves away and ceases to contact her, and her father loses his job with the Eagle Corporation of America. He shoots himself blind in an failed attempt to escape his debts through suicide, and the pair are evicted and lose all they own.

"An Elderly Gentleman" depicts an infirm, wealthy old capitalist. As the outlook of his business becomes bleaker, he lays off or reduces the wages of workers. He has organized labor in his factories suppressed through armed violence and murder. His infirmity worsens and he is bedridden, and he has a group of doctors work to cure him. As he recuperates, his lackeys inform him that profits have begun to rise again.

The young man of "The Boy" stands up to his abusive father, leaves home, and proposes marriage to the Girl. He sets off with his suitcase in fruitless search of work; when he returns, he finds his fiancée has been evicted, and is too embarrassed with his own situation to approach her. His search for work becomes increasingly desperate, and he considers turning to crime; he manages to make some money donating blood to the Elderly Gentleman.

Background

Born in Chicago,[3] Lynd Ward (1905–1985) was a son of Methodist minister Harry F. Ward (1873–1966), a social activist and the first chairman of the American Civil Liberties Union. Throughout his career, Ward displayed in his work the influence of his father's interest in social injustice.[4] The younger Ward was early drawn to art,[5] and contributed art and text to high school and college newspapers.[6]

_Die_Sonne_self-portrait.jpg)

After graduating from university[7] in 1926, Ward married writer May McNeer and the couple left for an extended honeymoon in Europe[8] Ward spent a year studying wood engraving in Leipzig, Germany, where he encountered German Expressionist art and read the wordless novel The Sun[lower-alpha 1] (1919) by Flemish woodcut artist Frans Masereel (1889–1972). Ward returned to the United States and freelanced his illustrations. In 1929, he came across German artist Otto Nückel's wordless novel Destiny[lower-alpha 2] (1926) in New York City.[9] Nückel's only work in the genre, Destiny told of the life and death of a prostitute in a style inspired by Masereel's, but with a greater cinematic flow.[7] The work inspired Ward to create a wordless novel of his own, Gods' Man (1929).[9] He continued with Madman's Drum (1930), Wild Pilgrimage (1932), Prelude to a Million Years (1933), and Song Without Words (1936), the last of which he made while engraving the blocks for Vertigo.[2] Each of these books sold fewer copies than the last, and publishers were wary of publishing experiments in the midst of the Depression.[10]

Production and publication history

Ward found the composition of Vertigo the most difficult of his wordless novels to manage;[11] he spent two years engraving the blocks,[1] which range in size from 3 1⁄2 × 2 inches (8.9 × 5.1 cm) to 5 × 3 1⁄2 inches (12.7 × 8.9 cm).[12] Ward discarded numerous blocks he was dissatisfied with,[13] using 230 in the finished work.[1] The book was published by Random House in November 1937.[14]

Following its initial publication the book was not reprinted for over seventy years.[10] It has since been reprinted by Dover Publications in 2009[15] and Library of America, in a 2010 complete collection of Ward's wordless novels.[16] The blocks for the book—including discards—are in the Special Collection of Rutgers University in New Jersey. The university hosted a display of the blocks in 2003.[13]

Style and analysis

The story was a criticism of the failures of capitalism during the Great Depression;[1] Ward stated the title "was meant to suggest that the illogic of what we saw happening all around us in the thirties was enough to set the mind spinning through space and the emotions hurtling from great hope to the depths of despair".[11] Ward had strong socialist sympathies and was a supporter of organized labor; the Boy expresses this union solidarity by abandoning the only job he could find rather than work as a strikebreaker.[17]

The pages are unnumbered; the stories are instead broken into parts and chapters.[11] The overlapping of stories encourages readers to revisit earlier portions as the characters appear in each other's stories.[11] Ward did away with borders in the compositions, allowing artwork to bleed to the edges of the woodblocks.[18] He manipulates the reader's focus with the variously-sized images, as in the small images that close in on the faces of the businessmen who surround the Elderly Gentleman.[18] The images are more realistic and finely detailed than in Ward's previous wordless novels,[1] and display a greater sense of balance of contrast and whitespace, and crispness of line.[18]

Ward employs symbols such as a rose, which takes different meanings in different contexts: creative beauty for the Girl, an item for purchase for the Elderly Gentleman. The same telephone system that provides the Elderly Gentleman with quick communication is an alienating, isolating symbol for the Boy, as it is beyond his means yet telephone poles are ever-present.[17] Ward displays discontinuous contrasts throughout the book: the Girl stretches herself out nude and carefree in a chapter of her section, while in his the Elderly Gentleman sadly views his worn-out naked form in a mirror.[19] While essentially wordless, via signs and placards the graphics incorporate far more text into the imagery than in earlier works.[20] To wordless novel scholar David Beronä, this shows an affinity to the development of the graphic novel, even if Vertigo itself is perhaps not comics;[20] Ward himself was not permitted to read comics in his youth.[21]

Ward aimed to present what he called "impersonal social forces" by depicting the individuals whose actions are responsible for those forces. Though the Elderly Gentleman's actions are at the heart of the misery of his workers, Ward depicts him with sympathy, sad, lonely, and alienated despite his wealth and charity.[22]

Reception and legacy

.jpg)

The success of Ward's early wordless novels led American publishers to put out a number of such books, both new American works and reprints of European ones.[23] Interest in wordless novels was short-lived,[24] and few besides Masereel and Ward produced more than a single work;[25] Ward was the lone American to produce any after 1932,[26] each of which sold fewer copies than the last.[10]

Upon release, reviewer Ralph M. Person was enthusiastic about the book on its release and the form's potential to "unshackl[e] the picture from its past limitation to the single scene or event" and place pictorial narrative in the realm of literature and theater.[27] Reviewer for the Evening Independent Bill Wiley proclaimed it "a dramatic story in a brilliant medium" that "will leave a vivid memory with the reader long after many novels in words are forgotten".[28] At the Sarasota Herald-Tribune John Selby found the book "more uniform in quality" than Ward's earlier wordless novels, yet "the book would 'read' more easily and produce a greater effect if the individual woodcuts were not so small".[29]

Vertigo was the last wordless novel Ward was to complete,[14] and has come to be seen as his masterpiece;[10] cartoonist Art Spiegelman called it "a key work of Depression-era literature".[2] In 1940 he abandoned another, to be titled Hymn for the Night, after completing twenty blocks of it. Ward found the story too far from his own immediate experience: a resetting of the Mary and Joseph story in Nazi Germany.[14] He turned to the making of stand-alone prints and book illustration for the remainder of his career.[30] In the late 1970s he began cutting blocks for another wordless novel, which remained unfinished on his death in 1985.[30]

An exhibition of the original woodblocks was held at Rutgers University in 2003. It was curated by Michael Joseph, and included numerous woodblocks Ward had discarded from the work.[13]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Beronä 2008, p. 76.

- 1 2 3 Spiegelman 2010a, p. xx.

- ↑ Spiegelman 2010b, p. 799.

- ↑ Beronä 2008, p. 41.

- ↑ Spiegelman 2010b, p. 801.

- ↑ Spiegelman 2010b, pp. 802–803.

- 1 2 Spiegelman 2010a, p. x.

- ↑ Spiegelman 2010b, pp. 803–804.

- 1 2 Spiegelman 2010b, pp. 804–805.

- 1 2 3 4 Ward & Beronä 2009, p. v.

- 1 2 3 4 Ward & Beronä 2009, p. vi.

- ↑ Beronä 2008, p. 248.

- 1 2 3 Ward & Beronä 2009, pp. vii–viii.

- 1 2 3 Spiegelman 2010b, p. 810.

- ↑ Vertigo in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- ↑ Lynd Ward: Six Novels in Woodcuts in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- 1 2 Ward & Beronä 2009, p. viii.

- 1 2 3 Ward & Beronä 2009, p. vii.

- ↑ Spiegelman 2010a, p. xxii.

- 1 2 Beronä 2008, p. 81.

- ↑ Spiegelman 2010a, p. xxiii.

- ↑ Spiegelman 2010a, pp. xxi–xxii.

- ↑ Ward & Beronä 2005, p. v.

- ↑ Beronä 2003, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Willett 2005, p. 131.

- ↑ Beronä 2003, p. 72.

- ↑ Ward & Beronä 2009, p. ix.

- ↑ Wiley 1937, p. 5.

- ↑ Selby 1937, p. 4.

- 1 2 Spiegelman 2010b, pp. 810–811.

Works cited

- Beronä, David A. (March 2003). "Wordless Novels in Woodcuts". Print Quarterly. Print Quarterly Publications. 20 (1): 61–73. ISSN 0265-8305. JSTOR 41826477.

- Beronä, David A. (2008). Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels. Abrams Books. ISBN 978-0-8109-9469-0.

- Ward, Lynd; Beronä, David (2005). "Introduction". Mad Man's Drum: A Novel in Woodcuts. Dover Publications. pp. iii–vi. ISBN 978-0-486-44500-7.

- Ward, Lynd; Beronä, David A. (2009). "Introduction". Vertigo: A Novel in Woodcuts. Dover Publications. pp. v–ix. ISBN 978-0-486-46889-1.

- Selby, John (1937-12-11). "The Literary Guidepost". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. p. 4.

- Spiegelman, Art (2010). "Reading Pictures". In Spiegelman, Art. Lynd Ward: God's Man, Madman's Drum, Wild Pilgrimage. Library of America. pp. ix–xxv. ISBN 978-1-59853-080-3.

- Spiegelman, Art (2010). "Chronology". In Spiegelman, Art. Lynd Ward: God's Man, Madman's Drum, Wild Pilgrimage. Library of America. pp. 799–821. ISBN 978-1-59853-080-3.

- Willett, Perry (2005). "The Cutting Edge of German Expressionism: The Woodcut Novel of Frans Masereel and Its Influences". In Donahue, Neil H. A Companion to the Literature of German Expressionism. Camden House Publishing. pp. 111–134. ISBN 978-1-57113-175-1.

- Wiley, Bill (1937-12-04). "Speaking of Books". The Evening Independent. p. 5.

Further reading

- Joseph, Michael, ed. (2003). Vertigo: A Graphic Novel of the Great Depression—An Exhibition of the Original Woodblocks and Wood Engravings by Lynd Ward. Rutgers University. OCLC 52100161.

External links

- Vertigo by Lynd Ward: An Exhibition and discussion of the dramatic and rhetorical use of small Images With Scans Taken From the Original Woodblocks by Michael Scott Joseph, Rare Books and University Archives, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, January 2003