Victoria Bridge (Montreal)

| Victoria Bridge Pont Victoria | |

|---|---|

Victoria Bridge as viewed from upstream, from Montreal Technoparc | |

| Coordinates | 45°29′30″N 73°31′45″W / 45.49165°N 73.52912°WCoordinates: 45°29′30″N 73°31′45″W / 45.49165°N 73.52912°W |

| Carries | |

| Crosses |

St. Lawrence River and Saint Lawrence Seaway |

| Locale | Saint-Lambert, Quebec and Montreal, Quebec (Neighbourhood of Victoriatown) |

| Characteristics | |

| Design |

|

| Piers in water | 24 |

| Clearance above | (?) |

| Clearance below | (?) |

| Number of lanes | 2, one each on either side of the rail bridge |

| Rail characteristics | |

| No. of tracks | 2 |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Structure gauge | AAR |

| Electrified | No |

| History | |

| Opened | August 25, 1860 |

| |

The Victoria Bridge (French: Pont Victoria), previously known as Victoria Jubilee Bridge, is a bridge over the St. Lawrence River, linking Montreal, Quebec, to the south shore city of Saint-Lambert.

Opened in 1859, originally as a tubular bridge designed by Robert Stephenson, the bridge was the first to span the St. Lawrence River, and as such is an important historic bridge in Canada. It remains in use to this day, carrying both road and rail traffic, with rails in the middle and roadways (part of Route 112) on both sides. It is actively used by the Canadian National Railway on its Halifax to Montreal main line. It is a major contributor to Montreal's role as a continental hub in the North American rail system. Its designation for the Canadian National Railway (CNR commonly known as CN) is Mile 71.40 Subdivision St-Hyacinthe.

Originally named the Great Victoria Bridge in honour of Queen Victoria, it was officially rededicated as the Victoria Jubilee Bridge following renovations in 1897 (A.D. MDCCCXCVII). It was returned to the name Victoria Bridge (Pont Victoria) in 1978.[1]

The bridge is approximately 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) long, and includes 24 ice-breaking piers.

History

.jpg)

The Victoria Bridge was erected between 1854 and 1859. Prior to the construction of the bridge, it was difficult and at times impossible to cross the St. Lawrence River during the long winter season, as freeze up and thawing in the fall and spring made for treacherous conditions. Crossings took place by boat during the summer, and by walking or riding a sleigh or cart over the frozen river in winter, along routes cleared of snow to facilitate passage.

A site for the bridge was selected by the eminent Canadian engineer Thomas Keefer. The structure was designed by Robert Stephenson (son of George Stephenson and the builder of the famed Rocket locomotive), and Alexander McKenzie Ross.

The chief engineer was James Hodges. The contractors were the English partnership of Peto, Brassey and Betts, who completed the bridge shortly after Stephenson's death in 1859.

The original deck was a long structural metal tube (a tubular bridge) made of prefabricated wrought iron sections made in England and shipped transatlantic. During its peak construction years a total of six steamboats, 72 barges, 3,040 men (of which there were several children between the ages of 8 and 12), 144 horses, and four locomotive engines were required to erect it at a cost of $6,600,000. The construction of the bridge was tied directly with that of the Grand Trunk Railway, a system headquartered in Britain which had been formed in 1852 with the support of the colonial government of the United Province of Canada to connect the Great Lakes with an ice-free port on the Atlantic Ocean (at Portland, Maine). When completed, it was the longest bridge in the world.

Victoria Bridge was officially inaugurated by Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales on August 25, 1860. The first freight train however had already passed over the bridge on December 12, 1859, and the first passenger train had crossed the bridge five days later on December 17. Queen Victoria had been invited to attend the opening of the bridge, but she declined the invitation and instead sent her eldest son, the Prince of Wales and heir to her throne.

In 1897–1898, the metal tube from 1860 was replaced by metal trusses, common at the time. To minimize traffic disruptions, the trusses were assembled around the tube, which permitted the tube to continue service to train traffic. The tube was then demolished. The stone piers from 1860, slightly altered in 1897, still testify to the excellent original engineering.

Between October 30, 1909 and October 13, 1956, the Montreal and Southern Counties Railway ran interurban streetcars on the Northern shoulder of the bridge. The line connected Granby and Montreal, with a later branch serving Longueuil.

The St. Lambert Diversion around the St. Lambert Locks was added in 1958 as part of the St. Lawrence Seaway project. This secondary bridge over the canal, south of the main bridge, also carries both road and rail, and is used when a ship is passing under the original alignment.

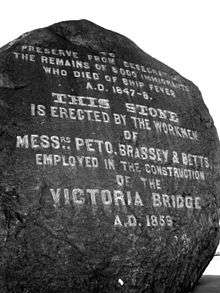

The Black Rock

When the bridge was being built, workmen discovered the human remains of Irish immigrants to Canada, who had fled the famine in Ireland, only to die during the typhus epidemic of 1847 in fever sheds at nearby Windmill Point.[2][3] At the bridge approach, a large rock was erected, officially called the Irish Commemorative Stone but locally known as The Black Rock.

Its inscription reads:

To preserve from desecration the remains of 6000 immigrants who died of ship fever A.D.1847-8 this stone is erected by the workmen of Messrs. Peto, Brassey and Betts employed in the construction of the Victoria Bridge A.D.1859.

Use

During the morning rush hour, from 6:00 am to 9:00 am, both lanes of the Victoria Bridge are used to travel north,[note 1] from the residential suburb of Saint-Lambert to the business districts of Montreal. In the evening, from 3:00 pm to 7:15 pm, both lanes are used in the opposite direction. At all other times, there is one lane available in each direction.

The only bus route allowed on the bridge is a special bus from the Réseau de transport de Longueuil, bus number 55. The line is served by Classic Buses due to weight restrictions on the bridge (57 customers if it is a classic one and 38 if it is a low-floor type bus). All other heavy vehicles are forbidden from accessing the bridge and must detour either via the neighbouring Champlain or Jacques-Cartier bridges. The low clearance on both approaches and the narrow lanes on the bridge itself make the bridge virtually inaccessible even to light trucks.

The laying of the last stone on the bridge by Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, 1860

The laying of the last stone on the bridge by Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, 1860 Victoria Bridge as it appeared in 1898

Victoria Bridge as it appeared in 1898 Victoria Bridge under construction

Victoria Bridge under construction Handbill showing Victoria Bridge and the names of the partners

Handbill showing Victoria Bridge and the names of the partners In 1948

In 1948

Notes

- ↑ Directions are according to traditional Montreal map where downtown (example, rue Sherbrooke) is east-west, with Mont-Royal to the north and the river to the south. "North" on the Victoria bridge is actually south-west.

References

- ↑ "Victoria, Pont." Commission de toponymie du Québec. Accessed 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Gallagher, The Reverend John A. (1936). "The Irish Emigration of 1847 and Its Canadian Consequences". CCHA Report, University of Manitoba Web site. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ↑ Lindeman, Tracey (2008-03-20). "Griffintown: a chronology". Montreal Mirror. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- Colin Churcher's Railway Pages (August 16, 2005), Significant dates in Canadian railway history. Retrieved August 25, 2005.

- Rapley, John (2003). The Britannia & Other Tubular Bridges, Tempus Publishing Ltd,

- Walker, Charles (1969). Thomas Brassey, Railway Builder. London: Frederick Muller. pp. 90–92. ISBN 0-584-10305-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Victoria Bridge, Montreal. |

- The Victoria Bridge - Virtual Exhibit (requires Flash plugin)

- Victoria Bridge (1859) at Structurae

- Victoria Bridge (1898) at Structurae

- Victoria Bridge: The 8th Wonder — a National Film Board of Canada short

- Robert W. Passfield, Construction of the Victoria Tubular Bridge, Canal History and Technology Proceedings 2001.