Virgin and Child Enthroned (van der Weyden)

The Virgin and Child Enthroned (or the Thyssen Madonna or Madonna in an Aedicula) is a small oil on oak panel painting attributed to the Early Netherlandish painter Rogier van der Weyden, and dated to c. 1430–32. It is closely related to his The Madonna Standing completed during the same period. It may have formed the left hand wing of a later dismantled diptych, perhaps with the Saint George and the Dragon now in Washington. It seems influence by Robert Campin, under whom van der Weyden trained; Campin's style is noticeable in the architecture of the niche, the Virgin's facial type, her exposed breast and the treatment of her hair.

The image is highly compact and contains imagery of prophets, the Annunciation to Mary, the infant Christ, his resurrection and Mary's eventual coronation in heaven. The work is generally accepted as the earliest extant work by van der Weyden, one of three attributed works showing the Virgin and Child enclosed in a niche positioned on a exterior wall of a Gothic church. As an early work, it betrays its influences, notably from Campin and Jan van Eyck.

Diptych

Some art historians have speculated that the panel was the left hand wing of a dismantled diptych, with the Washington Saint George and the Dragon of 1432–35 offered as the most likely opposite wing.[1] In that work, St. George, facing inwards and to the right, slays the dragon before a decidedly unexcited Libyan princess. Although the pairing might seem unlikely and incongruous, the artist's Madonna Standing is widely thought to have been attached with the St. Catherine of Alexandria in Vienna.[1]

Shirley Blum suggests that van der Weyden was establishing a juxtaposition between the otherworldly setting of the Madonna and Child and the earthly setting and historical dress of the saints. In both ancillary panels, the saints face inwards and away from the right hand painting. In both, they are positioned within fully realised landscapes, setting them in an earthly realm. In contrast, in both left hand panels, the Madonna and Child are positioned frontally (although eye contact is avoided) and isolated within cold grisaille architectural spaces. Blum describes the couplings as serving to position each saint "as a 'living witness' to the static, eternal presence of the Virgin and Child." She goes on to state that, "Only in such early works do we find this kind of obvious solution. By the time of the Descent and the Prado Madonna, Van der Weyden has already worked out a far more complex and effective means of mixing temporal and non-temporal effects".[2]

Description

_Detail3.jpg)

The painting is a Madonna Lactans and at 18.5cm x 12cm the smallest extant work by van der Weyden. It is bathed in very soft light, an influence from van Eyck. Falling from the right, the light leaves shadows of both Mary and the Child's heads on the wall of the niche.[3] The Virgin and Child are shown seated in a small Gothic chapel or oratory projecting from a wall and opening onto a lawn. The painting plays very close attention to small realistic detail; for example there are four small holes above each arch, likely intended to hold scaffolding.[4] There are some difference in symmetry between the left and right hand sides of the painting. This is most noticeable with the buttress, where the receding edges are over half again the size of those on the front sides. In addition, the breath of the buttress contradicts the spatial dept of the much tighter space inhabited by the Virgin and Child. Art historian John Ward notes this is an issue with foreshortening that Campin also struggled with, though van der Weyden did overcome in his more mature work.[5]

The chapel is unrealistically small compared to the Virgin; van der Weyden's intention was to emphasise the Virgin's presence while also symbolically representing the Church and the entire doctrine of the Redemption.[6] The panel is one three surviving van der Weyden's where both Madonna and Child are enclosed in this way. However it is unusual in that the niche exists as a separate feature within the picture, compared to the two other works where the enclosure is coterminous with the edge of the painting, almost as part of the frame. This is one reason why it is thought to predate The Madonna Standing.[3]

_-_WGA25572.jpg)

The Virgin appears oversized in comparison to the aedicula in which she sits; a very van Eyckian device, and later to reappear in van der Weyden's Prado Descent.[7] Mary's blond hair is unbound and falls across her shoulders and down to her arms. Betraying the influence of Campin, it is brushed behind the ears.[3] She wears a crown as Queen of Heaven and a ring on a finger as the Bride of Christ.[6] Reinforcing this, the blue colour of her robe alludes to her devotion and fidelity to her son.[8] The crisp folds of her dress are reminiscent of the lengthy and curved intertwine of gowns in Gothic sculpture.[4]

Christ is dressed in a red garment, as opposed to the swaddling he usually wears in 15th century Virgin and Child portrayals.[9] This painting represents one of two exceptions where he is fully clothed; the other is Campin's Madonna in Frankfurt, where he is shown in blue clothing.[10]

As with other early van der Weyden depictions of the Madonna, her head is slightly too large for her body. Her dress is creased and almost paper-like. However, the description of her lap contains inconsistencies also in Campin's Virgin and Child before a Firescreen; it appears to be bulk-less and as if she has only one leg. This seems to reflect the young artist's difficulty both with foreshortening and depicting a body under clothing.[5]

Iconography

The work is rich in symbolism and iconographic elements, to an extent far more pronounced than that in the The Madonna Standing. An iris grows to the side of the aedicula, representing the Virgin's sorrow at the Passion, and on the other side a columbine, recalling the Sorrows of the Virgin.[6] This symbolic use of flowers is again a van Eyckian motif. While they may appear incompatible with the architectural setting, this was probably the effect that van der Weyden was seeking.[11]

The lintel contains six reliefs from the New Testament showing scenes from the Life of the Virgin. The first four, the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Nativity and the Adoration of the Magi, are associated with motherhood and infancy. They are followed by the Resurrection and Pentecost. Above them, surmounting a "cross flower", is the Coronation of the Virgin.[6][9]

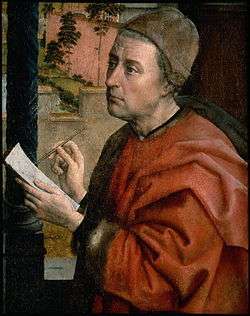

_Detail2.jpg)

The jambs on either side of the Virgin are adorned with statues representing the prophets of the Old Testament. The figures are mostly unidentified; only David, standing second to the left, can be identified, because he holds a harp. Reasonable deductions can be made as to the identity of other figures. The bearded figure to David's left is probably Moses, the man in the cap to the right is most likely the "weeping prophet" Jeremiah. On the opposite side, the outer figures may be the prophets Zechariah and Isaiah.[8]

By portraying these figures in grisaille, van der Weyden is making a distinction between the earthly, who are rendered as in flesh, and the divine, depicted frozen in time, as imitation sculpture.[11] Blum believes these figures were relegated to the architectural elements so as not to crowd the central devotional image.[7] The arrangement of these six figures may have been influenced by Claus Sluter's Well of Moses at the Chartreuse de Champmol, which has a similar alignment. In Champmol the prophets represent the judges of Christ (Secundum legem debet mori) and are thus tied to the crucifixion. In van der Weyden's work they are associated with the Virgin.[8] The motif of portraying figures in niches has a long tradition in Northern art; however, rendering them as sculpture was unique to the 1420s and 1430s, an innovation that first appeared in Jan van Eyck's Ghent Altarpiece. That work is perhaps in turn derived from Campin's 1420 Saint James the Great and Saint Claire.[3]

Dating and attribution

The work closely resembles van der Weyden's c 1430-32 The Madonna Standing, and seems influenced by the work of Robert Campin under whom he served his apprenticeship. It especially resembles Campin's 1430 Virgin and Child before a Firescreen, now in London, and one of the last works Campin completed before van der Weyden left his studio.[3] In both works the Virgin has large breasts, with fingers pressed to them to feed the Child. There are further similarities in her facial features, expression, her hair colour, its style and fall, as well as in her pose.[7] Lorne Campbell attributes the work to van der Weyden's workshop,[12] while John Ward attributes Campin and dates to it to c 1435.

.jpg)

Ward's thesis is based on the fact that the Thyssen panel is overwhelmingly influenced by Campin, while the contemporaneous and more sophisticated Madonna Standing draws heavily from van Eyck. He finds such a sudden shift unlikely, while also pointing out that this work evidences some technical difficulties that Campin was never to resolve, especially in respect to foreshortening and the rendering of the body underneath clothes. He also points to the architectural similarities to Campin's Marriage of Mary, although this may be a matter of influence.[13]

The painting was completed early in van der Weyden's career, probably just after his apprenticeship with Robert Campin ended. Although highly accomplished, it is filled with rather obvious symbolism of a kind absent from his more mature works. It is one of three attributed paintings, all early works, that show the Virgin and Child set within an architectural setting, surrounded with painted sculptural figures, the other two being The Madonna Standing and the Durán Madonna of 1435–38.[10][10]

Sculptural figuration was to become a hallmark of van der Weyden's mature work, and is best typified by the c. 1435 Madrid Descent, where the mourning figures are shaped and take on poses more usually seen in sculpture.[7] Erwin Panofsky identified this work and the The Madonna Standing as van der Weyden's earliest extant work; they are also his smallest panels. Panofsky dated both panels as 1432–34, and believed them to be early works based on stylistic reasons, their near miniature scale, and because of the evident influences of both Campin and van Eyck.[8]

Gallery

-

Robert Campin, Virgin and Child, c 1410, Frankfurt

-

_-_Prado_P02722.jpg)

van der Weyden, The Durán Madonna, c 1435–38, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Sources

References

- 1 2 Although the St. Catherine panel is usually attributed to his workshop, who would have based on an overall design by van der Weyden. See Panofsky (1971), 251

- ↑ Blum (1977), 121

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ward (1968), 354

- 1 2 Ward (1968), 356

- 1 2 Ward (1968), 355

- 1 2 3 4 Panofsky (1971), 146

- 1 2 3 4 Blum (1977), 103

- 1 2 3 4 Birkmeyer (1962), 329

- 1 2 Acres (2000), 83

- 1 2 3 Birkmeyer (1962), 330

- 1 2 Birkmeyer (1962), 331

- ↑ Acres (2000), 105

- ↑ Ward (1968), 354–356

Bibliography

- Acres, Alfred. "Rogier van der Weyden's Painted Texts". Artibus et Historiae, Volume 21, No. 41, 2000

- Blum, Shirley Neilsen. "Symbolic Invention in the Art of Rogier van der Weyden". Journal of Art History, Volume 46, Issue 1–4, 1977

- Birkmeyer, Karl M. "The Arch Motif in Netherlandish Painting of the Fifteenth Century". Art Bulletin, XLIII, Part 1, 1961

- Birkmeyer, Karl M. "Two Earliest Paintings by Rogier van der Weyden". The Art Bulletin, Volume 44, No. 4, 1962

- Hand, John Oliver; Metzger, Catherine; Spronk, Ron. Prayers and Portraits: Unfolding the Netherlandish Diptych. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-3001-2155-1

- Panofsky, Erwin. Early Netherlandish Painting: v. 1. Boulder CO: Westview Press, 1971. ISBN 978-0-0643-0002-5

- Ward, John. "A New Attribution for the Madonna Enthroned in the Thyssen Bornemisza Collection". The Art Bulletin, Volume 50, No. 4, 1968