Voortrekkers

_-_The_Voortrekkers.jpg)

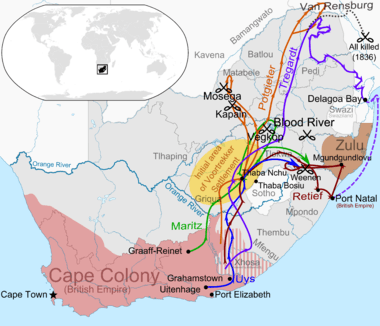

The Voortrekkers (Afrikaans and Dutch for pioneers, literally "fore-pullers", "those in front who pull", "fore-trekkers") mainly consisted of Trekboer pastoralists and Cape Dutch citizens from the Eastern frontier of the Cape Colony who during the 1830s and 1840s left the British controlled Cape; moving into the interior of what is now South Africa in what is known as the Great Trek. The Great Trek consisted of a number of mass movements under a number of different leaders. The Voortrekkers (and the Cape Dutch) are the direct ancestors of the Afrikaners of modern day South Africa. French Huguenot descendants were also included in the exodus of frontier farmers that was called the Great Trek.[1]

Leaders

Voortrekker Leaders arranged in order by size of party {number of families in brackets}:-[2]

- Hendrik Potgieter (19 DEC 1792- 16 DEC 1852), (his party included that of Sarel Cilliers), {158},

- Sarel Cilliers (7 SEP 1801 - 4 OCT 1871),

- Piet Retief (12 NOV 1780 - 6 FEB 1838), {139},

- Jan du Plessis, (his party included that of Jacobus Christoffel Potgieter), {116},

- Jacobus Christoffel Potgieter,

- Pieter Daniël Jacobs, {85},

- Petrus Lafras Uys (Piet) (1797 - 11 APR 1838), {79},

- Johannes Stephanus Maritz, {68},

- Gerhardus Marthinus Maritz (Gerrit / Gert) (1 MAR 1797 - 23 SEP 1838), {57},

- Karel Pieter Landman, {54},

- Jacob De Klerk, Jr., {52},

- Philippus Albertus Opperman, Sr., {41},

- Andries Pretorius (27 NOV 1798 - 23 JUL 1853), {38},

- Gerrit Reynier Van Rooyen, {29},

- Gerhardus Jacobus Rudolph, {26},

- Louis Jacobus Nel, {26},

- Lucas Johannes Meyer, {24},

- Joachim Christoffel Espag or Esbach, {23},

- Johan Hendrik De Lange, {15},

- Hercules Philip Malan, {13},

- Louis Tregardt (10 AUG 1783 - 25 OCT 1838), {13},

- Stephanus Petrus Erasmus, {9},

- Johannes Jacobus (Lang Hans) Janse van Rensburg (12 AUG 1779 - JUL 1836), {7},

- Arie Zacharias Visagie, {6},

- David Stephanus Fourie, {6},

- Jan Matthys De Beer, {6},

- Hermanus Stephanus Lombard, {2},

- Johannes Jacobus Erasmus, {1}.

The total number of families that trekked under a trek leader is 1093. From available sources it was found that during the years 1835 to 1845 a total of about 2540 families took part in the Great Trek.[3]

Origins

The Voortrekkers mainly came from the farming community of the Eastern Cape although some (such as Piet Retief) originally came from the Western Cape farming community while others (such as Gerrit Maritz) were successful tradesmen in the frontier towns. Some of them were wealthy men though most were not as they were from the poorer communities of the frontier. It was recorded that the 33 Voortrekker families at the Battle of Vegkop lost 100 horses, between 4,000 and 7,000 cattle, and between 40,000 and 50,000 sheep.

The Voortrekkers were mainly of Trekboer (migrating farmer) descent living in the eastern frontiers of the Cape. Hence, their ancestors had long established a semi-nomadic existence of trekking into expanding frontiers.[4] Amongst the Voortrekkers were poor men too belonging to the squatter or bywoner class.[5]

French Huguenot descendants were also included in the exodus of frontier farmers that was called the Great Trek.[6]

Voortrekker surnames who were of French huguenot ancestry include:[7]-

(Original french spelling in brackets)

- Aucamp (Auchamp)

- Boshof (Bossau)

- Bruwer (Bruere)

- Buys (Du Buis)

- Cilliers (Cellier)

- Cronje (Cronier)

- De Klerk (Le Clercq)

- Delport (Delporte)

- De Villiers

- Du Plessis

- Du Preez (Des Prez, Des Pres, Du Pre)

- Du Toit

- Duvenage (Duvinage)

- Fouche (Foucher)

- Fourie

- Hugo (Hugot, Hugod)

- Jacobs? (Jacob?)

- Jordaan (Jourdan)

- Joubert (Jaubert)

- Labuschagne (Labuscaigne)

- Le Roux

- Lombard (Lombaard)

- Malan (Mallan)

- Marais

- Maartens/Martins (Martin)

- Minnaar (Meinard, Mesnard)

- Meyer

- Naude

- Nel (Neel, Niel)

- Nortier / Nortje (Nourtier)

- Pienaar (Pinard)

- Retief (Retif)

- Reyneke? (Reyne?)

- Riekert? (Richarde?)

- Rossouw (Rousseau)

- Roux

- Senekal (Senecal, Senechal)

- Terblanche (Terreblanque)

- Theron (Therond)

- Tredoux

- Viljoen (Villion)

Reasons for the Great Trek

The reasons for the mass emigration from the Cape Colony have been much discussed over the years. Afrikaner historiography has emphasized the hardships endured by the frontier farmers which they blamed on British policies of pacifying the Xhosa tribes. Other historians have emphasized the harshness of the life in the Eastern Cape (which suffered one of its regular periods of drought in the early 1830s) compared to the attractions of the fertile country of Natal, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. Growing land shortages have also been cited as a contributing factor. The true reasons were obviously very complex and certainly consisted of both "push" factors (including the general dissatisfaction of life under British rule) and "pull" factors (including the desire for a better life in better country.)

Reasons for the Great Trek were many:-

- During the ten years following 1818, Natal south of the Tugela and most of the great plateau had been emptied of people by a cataclysmic disaster which black Africans still speak of with awe as the Mfecane - "the crushing."[8]

- The revocation of Lord Glenelg of the Province of Queen Adelaide and restoring it to the Xhosa.

- The continued chronic insecurity on the frontier.

- Being (wrongly) blamed by the (British) Government for provoking an unjust war.

- The Colony was perceived as being no place for Christian people to live.

- Land was becoming scarce and expensive owing to natural increase in the Afrikaans-speaking population and the advent of 5,000 British settlers during 1820.

- Persistent drought.

- The advance of the English tongue, especially in official circles, at the expense of the taal (Afrikaans language).

- The emancipation of the slaves ordained by the British in 1833.

- The inadequate compensation for the freed slaves by the British.

- The emancipation of the slaves took effect during harvest season.

- Chronic mortification at the way the Boers' actions were so freely criticized by the missionaries.

- The official recognition of the equality between colored men and whites.[9]

- The Commisie Treks returned filled with enthusiasm for the countries (Natal and Zoutpansberg) they had visited. In both places, they said, was land for the taking, land where their countrymen could set up independent states.[10]

- The British authorities had stopped ammunition being traded across the Orange, and someone like Jan Pretorius, the sub-leader of the Tregardt trek, wanted to buy gunpowder from the Portuguese in Lourenco Marques, and he thought that joining Tregardt's caravan was the safest way of getting there.[11]

History

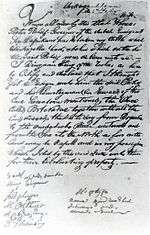

Piet Retief Delegation Massacre

The Voortrekkers migrated into Natal in 1837 and negotiated a land treaty in February 1838 with the Zulu King Dingane. Upon reconsideration, Dingane doublecrossed the Voortrekkers, killing the delegation of 100 including their leader Piet Retief on 6 February 1838. The land treaty was later found in Piet Retief's possession. It gave the Voortrekkers the land between the Tugela River and Port St. Johns.

Bloukrans (Weenen) Massacre

On 17 February 1838 Dingane sent an impi against the Voortrekkers which resulted in the Blaauwkrans Massacre where over 500 Voortrekkers were killed by Zulu warriors.

Amongst those killed were:-

- Joachim Johannes Prinsloo, ≈ 30/3/1783 (Acquitted Slagtersnek rebel)[12]

- Martha Louisa Prinsloo, (Wife of Joachim Johannes Prinsloo, above)[13]

Battle of Italeni

After the massacre of Piet Retief and his men by Dingane on 6 February 1838, a number of Voortrekker camps were also attacked by the Zulu impis. These Voortrekkers appealed to other treks, particularly those of Piet Uys and Hendrik Potgieter in the Orange Free State, for help. Both treks sent out commandos to help.

During the subsequent fighting against the Zulu, Uys, his son, the Malan brothers, and five of the volunteers were killed: 64-65 (for ten Voortrekker dead during the battle). The part of Uys' commando that remained behind (under the command of Field Cornet Potgieter), were surrounded and had to fight their way out. Due to the outcome of the battle, the Voortrekker forces involved in the fighting subsequently became known as the Vlugkommando (Flight Commando).

Battle of Blood River

Andries Pretorius filled the Voortrekker leadership vacuum, hoping to punish Dingane, retrieve stolen livestock and reclaim the land Dingane had granted to Retief. When Dingane sent an impi (armed force) of around 15,000 to 21,000 Zulu warriors to attack the local contingent of Voortrekkers in response, the Voortrekkers sent out the Vegkommando (Fight commando) and in turn defended themselves at a battle at Ncome River (called the Battle of Blood River) on 16 December 1838, where the vastly outnumbered Voortrekker contingent defeated the Zulu warriors. This date later became known as the Day of the Vow, as the Voortrekkers made a vow to God that they would honor the date if he were to deliver them from what they viewed as almost insurmountable odds. The victory of the besieged Voortrekkers at Ncome River was considered a turning point.

The Voortrekkers set up the Natalia Republic in 1839 which was situated between the Tugela River and Port St. Johns as per the land treaty between Dingane and Retief, but Britain annexed this area in 1843, whereupon most of the local Boers trekked further north, joining other Voortrekkers who had established themselves in that region.

Migration to the Waterberg

Other Voortrekkers migrated north to the Waterberg area, where some of them settled and began ranching operations, which activities enhanced the pressure placed on indigenous wildlife by pre-existing tribesmen, whose Bantu predecessors had previously initiated such grazing in the Waterberg region. These Voortrekkers arriving in the Waterberg area believed they had reached the Nile River area of Egypt - based upon their understanding of the local topography.[14][15]

Struggle against the Ndebele

Armed conflict, first with the Matabele people (a.k.a. Northern Ndebele) under Mzilikazi in the area which was to become the Transvaal, then against the Zulus under Dingane, went the Voortrekkers' way, mostly because of their tactics, their horsemanship and the effectiveness of their superior technology in the form of muzzle-loading guns. This success led to the establishment of a number of small Boer republics, which slowly coalesced into the Orange Free State and the South African Republic or were absorbed by the British Empire. These two states would survive until their annexation in 1900 by the United Kingdom during the Second Anglo-Boer War.

Culture

The Pionier Museum in Pretoria is housed in an early Voortrekker house and is a 'living museum' displaying the daily lives and practices of a typical Voortrekker family. The pioneers relied heavily on preserved foodstuffs such as Beskuit, Biltong and Droëwors.

Memorials

The Voortrekkers are commemorated by the Voortrekker Monument located on Monument Hill overlooking Pretoria, the erstwhile capital of the South African Republic and the current and historic administrative capital of the Republic of South Africa. Pretoria was named after the Voortrekker leader Andries Pretorius.

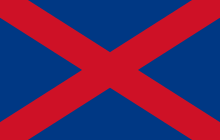

The Voortrekkers had a distinctive flag, used mainly by the Voortrekkers who followed Andries Hendrik Potgieter, which is why it was also known as the Potgieter Flag. This flag was used as the flag of the Zoutpansberg Republic until this republic was incorporated into the Transvaal Republic also known as the South African Republic. A version of this flag was used at Potchefstroom, one of the first independent Boer towns and republics established by local Voortrekkers.

See also

- Trekboers

- Voortrekker Monument

- Great Trek

- Weenen massacre

- Battle of Blood River

- Boer republics

- Transvaal civil war, 1854 conflict

- First Boer War, 1880 conflict

- Bandeirantes (pioneers of the Brazilian mainland)

Footnotes

- ↑ Bryer, Lynne and Theron, Francois. The Huguenot Heritage, The Story of the Huguenots at the Cape. Chameleon Press. Diep River. First Edition. 1987. Page 47.

- ↑ Visagie, Jan C. Voortrekkerstamouers 1835 - 1845. Protea Boekhuis. Pretoria. 2011. Page 15.

- ↑ Visagie, Jan C. Voortrekkerstamouers 1835 - 1845. Protea Boekhuis. Pretoria. 2011. Page 14 and 15.

- ↑ Brian M. Du Toit. The Boers in East Africa: Ethnicity and Identity. Page 1.

- ↑ Ransford, Oliver. The Great Trek. John Murray. Great Britain. 1972. Page 37.

- ↑ Bryer, Lynne and Theron, Francois. The Huguenot Heritage, The Story of the Huguenots at the Cape. Chameleon Press. Diep River. First Edition. 1987. Page 47.

- ↑ Visagie, Jan C. Voortrekkerstamouers 1835 - 1845. Protea Boekhuis. Pretoria. 2011.

- ↑ Ransford, Oliver. The Great Trek. John Murray. Great Britain. 1972. Page 26.

- ↑ Ransford, Oliver. The Great Trek. John Murray. Great Britain. 1972. Pages 21 and 22.

- ↑ Ransford, Oliver. The Great Trek. John Murray. Great Britain. 1972. Page 23.

- ↑ Ransford, Oliver. The Great Trek. John Murray. Great Britain. 1972. Pages 36 and 37.

- ↑ Visagie, Jan C., Voortrekkerstamouers 1835 - 1845. Protea Boekhuis, Pretoria, 2011. ISBN 978-1-86919-372-0. Page 401.

- ↑ Visagie, Jan C., Voortrekkerstamouers 1835 - 1845. Protea Boekhuis, Pretoria, 2011. ISBN 978-1-86919-372-0. Page 401.

- ↑ Taylor, 2003

- ↑ Lumina, 2006

References

- William Taylor, Gerald Hinde and David Holt-Biddle, The Waterberg, Struik Publishers, Cape Town, South Africa (2003) ISBN 1-86872-822-6

- Lumina Tech, C.Michael Hogan, Mark L. Cooke and Helen Murray, The Waterberg Biosphere, Lumina Technologies, May 22, 2006.

External links

- The Voortrekker Monument.

- History of the Voortrekker monument

- Voortrekker Monument in Depth.

- 360 degree Virtual Tour of Voortrekker Monument