War of the League of the Indies

| War of the League of the Indies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

16th century Portuguese carracks (naus) and galleys | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Over 25,000 | ||||||

The War of the League of the Indies (December 1570 – 1574) was a military conflict in which an alliance formed primarily by the Sultanate of Bijapur, the Sultanate of Ahmadnagar, the Kingdom of Calicut and the Sultanate of Aceh, attempted to decisively overturn Portuguese presence in the Indian Ocean through a combined assault on some of the main posessions of the Portuguese State of India: Malacca, Chaul, Chale fort, and the capital of the maritime empire in Asia, Goa.

Referred to by the Portuguese historian Diogo do Couto as the Great League of Kings of the Indies (Grande Liga dos Reis da Índia), the Portuguese successfully resisted all sieges against the "League", in what was one of the most critical moments of Portuguese presence in Asia, with the exception of a small fort in the outskirts of Calicut that fell to the Zamorin. It would be the first forceful territorial loss the Portuguese suffered in Asia.[2]

Although anachronistic in concept, it was a total war, as the Portuguese were forced to mobilize every available means to resist the assault.[3]

Background

In 1565, the Deccan sultanates joined forces to strike a decisive blow against the Vijayanagara Empire at the Battle of Talikota. The Hindu Vijayanagara Empire had been engaged in an incessant, irregular war against each of the Muslim sultanates of the Deccan Plateau individually, well before the Portuguese arrived in the Indian Ocean. The ruler of Vijayanagara, Rama Raya (whom the Portuguese referred to as simply the Rei Grande - "Great King") was a powerful ally of the Portuguese but with the Empire now thrown into chaos and plundered, the Adil Shah of Bijapur proposed joining forces with the Nizam of Amhadnagar to recover what they had previously lost to the Portuguese over half a century ago and had failed to recover ever since: The cities of Goa and Chaul respectively. According to contemporary Portuguese chroniclers, the war was also motivated by religious reasons. Envoys were then dispatched to the Sultanate of Aceh in Sumatra, Ottoman Turkey and the Zamorin of Calicut among others urging them to join the alliance and defeat the Portuguese once and for all.

The Ottoman Empire

The Sultans of Bijapur and Ahmadnagar dispatched ambassadors to Constantinople with rich presents and a large tribute to gain the cooperation of the Ottoman navy, in wresting the control of the seas from the Portuguese. The Ottomans had bases in the Red Sea following the annexation of Egypt in 1517 and Sultan Selim II promptly agreed to join the effort. 25 galleys and 3 galleons set out from the Suez, but they were held back by revolts in the Hejaz and Aden, and the forthcoming Ottoman campaigns in the eastern Mediterranean, such as the the Fourth Ottoman-Venetian War (which would culminate in the Battle of Lepanto) ensured that Turkey would not participate in the conflict.[4]

Portuguese preparations

Reports and rumours of the preparations of the Adil Shah and the Nizam began reaching Goa through Portuguese merchants and allies by the beginning of 1570. Although skeptical at first, believing the distrust between Indian rulers to be insurmountable for such a plan to be possible, the Portuguese Viceroy, Dom Luís de Ataíde eventually decided to dispatch a fleet of five galleons, one galley and seven galliots with 800 men under the command of Dom Luís de Melo da Silva in August 24 to Malacca to reinforce the city against a possible attack from the Sultanate of Aceh. Another fleet of three galleys and seventeen galliots with 500 men, under the command of Dom Diogo de Meneses was sent to patrol the Malabar coast and keep the vital trade routes with southern India, where the Portuguese city of Cochin was located, open and free of raiding from pirates.

Dom Luís de Ataíde, a veteran from wars in India and the campaign of Emperor Charles V against the Lutherans in Europe, then gathered a council with some of the most important figures in Goa, including noblemen, clergymen and members of the town hall of Goa. The council advised him to abandon Chaul and concentrate his forces around Goa, but nevertheless, in October he decided to dispatch a further fleet with 600 men commanded by Dom Francisco de Mascarenhas to defend that city. As the Viceroy was left with no more than 650 soldiers to defend Goa, every able-bodied man from among the casados (married settlers and Indo-Portuguese descendants) and 1500 Christian lascars were mobilized to defend the city; 1000 slaves, divided into four squadrons were armed, and even a further 300 clergymen and 200 retired soldiers volunteered to participate in its defence.[5]

As the Viceroy had information that the Turks could possibly join the "league", he armed a further 125 crafts of many different sizes to secure the control of the waters around Goa, although by then there weren't enough men to crew all the ships and defend the city simultaneously.

The Siege of Goa

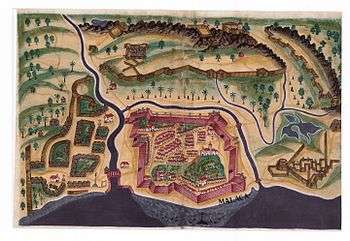

Conquered by Afonso de Albuquerque in 1510, Goa stood on an island surrounded by crocodile infested rivers that could, however, be waded across in some areas during the dry season. The closest and most important fording point to the city of Goa was the Passo Seco ("Dry Pass"), defended by the fortress of Benastarim. Dom Luís de Ataíde decided to distribute his forces in 19 critical points along the eastern river banks, where artillery batteries were assembled, garrisoned with 20 to 80 men, to keep the colossal army of Bijapur from wading across. Every battery was to have visual contact with the next and their garrisons were not to leave their posts unless ordered to. The deeper waters of the Mandovi and Zuari rivers, to the north and south respectively, were patrolled by four galleys, a galleot and twenty small galliots called foists. On the opposite shore northwest of Goa, the Portuguese fortress of Reis Magos was supported by an anchored galleon.

By December 1570, the Adil Shah of Bijapur (The Hidalxá in Portuguese sources) assembled his army to the east of the island of Goa, which according to the Portuguese was 100,000 men strong, of which 30,000 were foot, 3,000 arquebusiers and 35,000 horse, including 2000 elephants, while the remaining were forced labourers. Besides over 350 bombards of which 30 were of colossal size, the army was also accompanied by several thousands of dancing women.

Adil Shah began assembling his infantry ahead of Benastarim and ordering artillery to be placed into position to counter-fire the Portuguese batteries. On December 28, the artillery of Bijapur began battering the fort, which was constantly repaired during the night. All throughout the Portuguese lines by the river banks, the Viceroy ordered torches and bonfires be lit on isolated positions by night, to encourage the enemy to fire on them and waste ammunition.[6]

Unable to ferry his troops across since the Portuguese controlled the river waters, the Adil Shah ordered that the part of the river closest to the city be filled up with dirt to allow the army to cross over, forcing the labourers to dig under Portuguese fire:

[the Adil Shah] determined to pass over a causeway that he ordered be made (to the Island of João Gomes, from where the entry [into the city] would be very easy) by the great amount of labourers that he had. And for all that were killed there, never would he give up the digging, for the Moors care so little for these people that they barely have them as a loss and for as many that they lost there, never were they short of more.[7]

By February of 1571, the attack had ground down to a standstill, as the army of Bijapur was unable to overcome Portuguese defenses. Four Portuguese galliots set out from Goa to the River Chaporá, where they intercepted 30 merchant ships with supplies to the army of Bijapur, burned down several villages and captured large quantities of cattle that was brought back to Goa.

In March 13, the Adil Khan ordered a decisive assault across the river, under the command of a Turk, Suleimão Agá. 9,000 men waded across the river either by foot or on small crafts and many reached the opposite banks, but came under heavy fire from Portuguese ships, artillery batteries and arquebuses, until they were finally shattered by a Portuguese counter-attack under the command of Luís de Melo and Dom Fernando de Monroy, who landed a force of 300 men in the opposite shore, killing about 3,000 enemies. By the late afternoon, a strong storm spelled the end of the assault.

As the weather worsened with the coming of the monsoon rains, the Adil Shah kept his army camped in front of Goa, while torrential storms forced operations down to a minimum and the Portuguese conducted occasional raids under the rain. By August the 15th,[8] with his army profoundly demoralised, afflicted by the monsoon weather and suffering from shortage of supplies, the Adil Shah ordered the steady withdrawal of his forces, having lost over 8,000 men, 4,000 horses, 300 elephants and over 6,000 oxen in the campaign,[9] abandoning 150 pieces of artillery in the river.[10] By December 13, 1571, the Shah formally requested peace with the Portuguese.

Siege of Mangalore

As the Vijayanagara Empire collapsed, the Portuguese took possession of the port city of Mangalore in 1568, where they constructed a small fort to prevent the city from falling to Muslim control. In 1571 however, the Queen of Mangalore contracted a Malabarese pirate, whom the Portuguese identified as Catiproca Marcá, to capture the fort that was by then defended solely by 15 Portuguese soldiers. Catiproca had 8 galliots, and in April 1571 his forces attempted to scale the fort's walls in the middle of the night. He was detected, and the small garrison managed to repel the attack.[11] Having failed the attack, Catiproca reembarked his forces but two days later he encountered the fleet of Dom Diogo de Meneses, who had been sent to the Malabar coast specifically to ensure the safety of allied shipping from pirates, and his fleet destroyed.[12]

Siege of Onor

In 1569 the Portuguese built a small fort by the coastal town of Onor (Honavar), that was attacked by 5,000 men and 400 horse of the Queen of Honavar in the middle of July of 1571, during the monsoon. The Viceroy dispatched 200 men to reinforce the fort by sea aboard a galley and eight foists. The small fleet managed to reach the fort despite the monsoon weather and immediately conducted a successful attack on the enemy army and the fort held on.[13]

The Siege of Chaul

Although protected by a small fort built near the shoreline in 1521, the city of Chaul was not fortified. Just as the threat of a siege became evident, the captain of the city, Dom Luís Freire de Andrade ordered the evacuation of women, children and elderly to Goa and barricades be set up in the main streets with artillery. In October, Dom Francisco de Mascarenhas arrived from Goa with 600 men and immediately ordered the digging of an extensive network of ditches, trenches, earthen walls and defensive works around the outer perimeter of the city, fortifying outer households into blockhouses and demolishing others to clear the line of fire for the artillery.[14]

In December 15, the vanguard of the army of Ahmadnagar arrived under the command of an Ethiopian general, Faratecão (formerly at the service of the Sultan of Gujarat), and clashed with the Portuguese, who repel the attack.[15] The Nizam arrived with the rest of his army in December 21.[15] The forces of the Nizam Ul-Mulk Shah of Ahmadnagar (Nizamaluco in Portuguese) may have risen up to 120,000 men, including many Turkic, Abyssian, Persian and Mughal mercenaries, 38,000 horsemen and 370 war elephants, supported by 38 heavy bombards. According to António Pinto Pereira:

The infantry passed one-hundred and twenty thousand, but they do not rest on them their strength, nor do they bother training but the cavalry and artillery for war; the footmen are brought along as cannon fodder and for service in the camp as labourers. In said camp came 12,000 konkanis, very good people in war, mustered by the tanadares of their lands, as bomb throwers, bowmen and a few arquebusiers and 4,000 field craftsmen, blacksmiths, stonemasons and carpenters.[16]

The Nizam assembled the rest of his forces around the north and northeast the city, and in the 21st day of December breach the fortified perimeter around the monastery of São Francisco in the outskirts of Chaul, but face the heavy fire of Portuguese arquebuses and a swift counter-attack forced them to retreat. In the meantime, the Nizam set his powerful artillery to the east of the city under the supervision of a Turkish general, Rumi Khan, near a village the Portuguese dubbed Chaul de Cima (Upper Chaul).

In January 10, the batteries of the Nizam began bombarding the outer blockhouses of Chaul, reducing them to rubble after a few days. One such piece earned from the Portuguese the nickname "Orlando Furioso".[17]

At the same time, the cavalry of the Nizam proceeded to devastate the lands owned by Portuguese around Bassein and Daman, but were repelled when 2,000 horsemen tried to assault a small Portuguese fort at Caranjá near Bombay, defended by 40 men.

In February, a small fleet of 5 galliots and 25 smaller craft with 2,000 men from Calicut, commanded by Catiproca Marcá, arrived in Chaul to meet up with the forces of the Nizam, under cover from the night. The Portuguese had five galleys and eleven foists in the harbour, but the Malabarese avoided clashing with the Portuguese galleys.[18]

Fighting around Chaul broke down to trench warfare, as the army of Ahmadnagar dug trenches towards Portuguese lines to cover from their gunfire, amidst frequent Portuguese raids. The Portuguese dug counter-mines to neutralize them. In late February the Nizam ordered a general assault on the city, but was repelled with heavy losses, just as the Portuguese received important reinforcements by sea from Goa and Bassein. Fighting continued over the possession of the outer strongholds along the months of March, April and May, as the army of the Nizam suffered heavy casualties. Following a sortie of the Portuguese in April 11, the Nizam ordered the city to be subjected to a general bombardment, which demolished several strongholds and sunk the Viceroy's galley anchored in the harbour (a cannonball from the largest cannon of the Nizam bounced off a fortified blockhouse, demolishing it, and then hit the galley).

In June 29, the Nizam ordered another mass assault but after six hours fighting, they were repelled, suffering over 3,000 dead. Following this setback, the Nizam requested peace on July 24, 1571, and withdrew his army.

The Siege of Chale, 1571

The Sultans of Bijapur and Ahmednagar considered the naval forces of Calicut vital in contesting the sea lanes from the Portuguese. Although formally at peace, the Zamorin nevertheless waited until the monsoon started to siege the Portuguese fortress by the coastal town of Chale (Chaliyam), hoping that the weather would prevent the Portuguese from shipping over reinforcements. By July the Zamorin initiated the attack, bombarding the fortress with 40 cannons. Despite the weather, the Portuguese managed to send reinforcements and a few supplies through to the fortress as soon as news of the attack reached Goa. The Zamorin placed an artillery battery on the mouth of the river that effectively blockaded Portuguese shallow draft vessels from passing through. The captain of the fortress, 80-year-old Dom Jorge de Castro, influenced by the King of Tanor a local ally of the Portuguese, decided to surrender the fortress on November 4, 1571 in what became the first forceful loss of territory suffered by the Portuguese ever since arriving in India. The Zamorin immediately demolished the fort and sent Dom Jorge back to Goa. At Goa, Dom Jorge was arrested, and taken to a military trial, which concluded that given the circumstances he had enough means to resist a prolonged siege, and was formally executed.

With the withdrawal of the forces of Adil Khan from Goa, the Portuguese then passed on the offensive against the Zamorin, blockading Calicut and devastating the kingdom, until he was also forced to sue for peace.

The Siege of Malacca, 1573

The reinforcements sent from Goa in August of 1570, under the command of Dom Luís de Melo da Silva, proved critical in preventing Malacca from being besieged at the same time as Goa and Chaul: In November 1570, the Portuguese destroyed an Aceh fleet of 60 ships by the mouth of River Formoso to the south of Malacca, killing the prince-heir of Aceh, and thus forcing the Sultan to postpone the attack to a later date.[19]

Nevertheless, by October 1573 Malacca was scarcely defended and the Sultan of Aceh had gathered 7,000 men and a fleet of 25 galleys, 34 galliots and 30 craft and requested assistance from the Queen of Kalinyamat (Japará in Portuguese) to siege it. Without waiting for his ally, in October 13 the Aceh force landed south of Malacca and began attacking the fortress with incendiary projectiles, causing several fires. A sudden storm took out the fires and scattered the fleet, and the assault was called off. The Aceh commander then decided to establish a naval base by the Muar River and force the city to surrender through a naval blockade instead, capturing any passing tradeships that carried supplies to the city. An attempt to board a galleon and two carracks anchored by the harbour was met with heavy resistance and suffered severe casualties from Portuguese gunfire.

In November 2, a carrack commanded by Tristão Vaz da Veiga arrived with the newly appointed captain of Malacca, Dom Francisco Rodrigues, along with important reinforcements. The captain immediately summoned a council to assess the situation. The Aceh fleet was causing severe shortages in Malacca, and it was decided that it was urgent to organize a force to repel it as soon as possible. Thus, a carrack, a galleon and eight galliots were munitioned and set out on November 16 to the mouth of the River Formoso, where the enemy fleet had shifted to. With the river in sight, the Aceh fleet set out while the wind was in their favour to meet the Portuguese. Despite outnumbered, the Portuguese oar ships positioned themselves ahead of the carrack and the galleon to board the Acehnese galleys in the vanguard, after firing volleys of shrapnel and matchlock fire and throwing gunpowder grenades, while the carrack and the galleon fired their heavy caliber artillery, sinking many Acehnese oar ships. Despite having Turkish gunners and cannon, the Acehnese artillery was not overly effective. Once their flagship, a very large galley with over 200 fighting men, was boarded and its flag taken down by the Portuguese, the remainder of the Aceh fleet scattered, having lost four galleys and five galliots, with several more sunken or beached due to the bad weather.

Siege of Malacca, 1574

Despite the Aceh defeat, the Queen of Kalianyamat organized an armada with which to attack Malacca, composed of over 70 junks and over 200 craft carrying 15,000 men under the command of Ki Demat - transliterated as Queahidamão by the Portuguese - although with very little artillery and firearms. Malacca was defended by about 300 Portuguese.

By October 5, 1574, the armada anchored within the nearby River of Malaios and began landing troops, but the besiegers suffered Portuguese raids that caused great damage to the army when assembling stockades around the city.

As the then captain of Malacca (on account of the sudden death his predecessor), Tristão Vaz da Veiga decided to arm a small fleet of a galley and four galliots and about 100 soldiers and head out to the River of Malaios, in the middle of the night. Once there, the Portuguese fleet entered the river undetected by the Javanese crews, and resorting to hand-thrown fire bombs set fire to about thirty junks and other crafts, catching the enemy fleet entirely by surprise, and capturing ample supplies amidst the panicking Javanese. Ki Demat afterwards decided to fortify the river mouth, constructing stockades across the river, armed with a few small cannon, but it too was twice destroyed by the Portuguese. Afterwards, Tristão Vaz da Veiga ordered Fernão Peres de Andrade to blockade the rivermouth with a small carrack and a few oarships, trapping the enemy army within it and forcing the Javanese commander to come to terms with the Portuguese. Not coming to any agreement, in December Tristão Vaz finally ordered his forces to withdraw from the rivermouth. The Javanese hastily embarked in the few ships they had left, overloading them, and sailed out of the river, only to be then preyed by Portuguese ships, who chased them down with their artillery. The Javanese lost almost all of their junks and suffered about 7,000 dead at the end of the three-month campaign.

Aftermath

Besides proving the difficulty of organizing an attack of such a wide scale, the combined assault of some of the most powerful kingdoms in Asia on Portuguese possessions failed to achieve any significant objectives, let alone decisively overturn Portuguese influence in the Indian Ocean. On the contrary, the rulers of Bijapur, Ahmadnagar and the Zamorin were forced to come to terms that were favourable to the Portuguese: among other terms, they would charge no fees from Christian merchants and harbour no enemy fleets of the Portuguese, in exchange for Portuguese assistance in clearing the western Indian coast of piracy and authorization to trade in Portuguese ports (provided every ship carried an appropriate trading license, or cartaz), essentially recognizing Portuguese dominion of the sea.[20][21]

The fort of Chale had little strategic interest, and its loss did not represent a serious setback for the Portuguese.[22] The fall of Vijayanagara however, had indirectly greater strategic implications for the Portuguese State of India, whose finances suffered a severe blow with the loss of the extremely lucrative horse trade with the Empire.[23] It would take the assistance of other European powers to challenge the hegemony of the Portuguese, who would suffer their first serious setback with the fall of Hormuz, at the hands of combined Anglo-Persian force, about forty years later in 1622.

References

- António Pinto Pereira (1572-1578), História da Índia, ao Tempo Que a Governou o Vice-Rei D. Luiz de Ataíde, 1986 edition, Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda.

- Diogo do Couto (1673), Da Ásia, Década Oitava, 1786 edition, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

- Diogo do Couto (1673), Da Ásia, Década Nona, 1786 edition, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

- Jorge de Lemos (1585) História dos Cercos de Malaca

- Saturnino Monteiro (1992), Portuguese Sea Battles, Volume III - From Brazil to Japan, 1539-1579.

- Gonçalo Feio (2013), O ensino e a aprendizagem militares em Portugal e no Império, de D. João III a D. Sebastião: a arte portuguesa da guerra. University of Lisbon.

Notes

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1992), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume III - From Brazil to Japan, 1539-1579 p. 328

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1992), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume III - From Brazil to Japan, 1539-1579 p.339

- ↑ Gonçalo Feio (2013), O ensino e a aprendizagem militares em Portugal e no Império, de D. João III a D. Sebastião: a arte portuguesa da guerra p.135

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1992), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume III - From Brazil to Japan, 1539-1579 pp. 334–340

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 349.

- ↑ Diogo do Couto (1673), Da Ásia, Década Oitava, 1786 edition, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal p.557

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 411.

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 624.

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 625.

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 623.

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 461.

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 464.

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 574.

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 361-353.

- 1 2 Pereira 1572-1578, p. 368.

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 380.

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 381.

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1992), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume III - From Brazil to Japan, 1539-1579 pp. 344–346

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1992), Portuguese Sea Battles, Volume III - From Brazil to Japan, 1539-1579. pp.327-330

- ↑ Pereira 1572-1578, p. 616-618.

- ↑ Diogo do Couto (1673), Da Ásia, Década Nona pp.17–19, 1786 edition, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal

- ↑ Monteiro 1992, p. 339.

- ↑ Monteiro 1992, p. 371.