Western Ukraine

| Western Ukraine | |

|---|---|

| Region | |

|

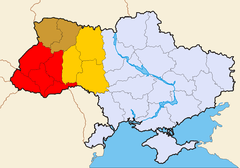

Several Oblasts can be referred to as "Western Ukraine" today: Red - always included Brown - often included Orange - sometimes included | |

| |

|

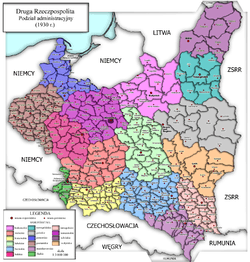

Administrative map of Poland, 1930. See: south-eastern regions (blue/purple/pink/beige) |

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine (Ukrainian: Західна Україна) is a geographical and historical relative term used in reference to the western territories of Ukraine. Important cities are Buchach, Chernivtsi, Drohobych, Halych (hence - Halychyna), Ivano-Frankivsk, Khotyn, Lutsk, Lviv, Mukacheve, Rivne, Ternopil, Uzhhorod and others. Western Ukraine is not an administrative category within Ukraine. It is defined mainly in the context of European history pertaining to the 20th century wars and the ensuing period of annexations. The current oblast administration borders are almost perfectly aligned with the administrative divisions of the Second Polish Republic from before the 1939 invasion of Poland by the Soviet Union. At the onset of World War II the region was incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (УРСР),[1][2][3][4] following mock elections which manufactured public consent for the transfer of land from occupied Poland to the Soviet Union as of October 22, 1939.[5] Its historical background makes Western Ukraine uniquely different from the rest of the country, and contributes to its distinctive character of today.[6]

History

Unlike the rest of Ukraine, most of Western Ukraine was never part of the Russian empire.[4] It is the only territory in Ukraine whose administrative units are named after its own historic regions often going back centuries, instead of their administrative centers which are used conventionally throughout the rest of the country. The modern south-western part of Western Ukraine became a province of Austria-Hungary after the partitions of Poland. Its northern flank with the cities of Lutsk and Rivne was acquired in 1795 by Imperial Russia following the third and final partition of Poland. Throughout its existence Russian Poland was marred with violence and intimidation, beginning with the 1794 massacres, imperial land-theft and the deportations of the November and January Uprisings.[7] By contrast, the Austrian Partition with its Sejm of the Land in the cities of Lviv and Stanislavov (Ivano-Frankivsk) was freer politically perhaps because it had a lot less to offer economically.[8] Imperial Austria did not persecute Ukrainian organizations.[4] In later years, Austria-Hungary de facto encouraged the existence of Ukrainian political organizations in order to counterbalance the influence of Polish culture in Galicia. The southern half of West Ukraine remained under Austrian administration until the collapse of the House of Habsburg at the end of World War One in 1918.[4]

Interbellum and World War II

Following the defeat of Ukrainian People's Republic (1918) in the Ukrainian–Soviet War of 1921, Western Ukraine was partitioned by the Treaty of Riga between Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and the Soviet Russia acting on behalf of the Soviet Belarus and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic with capital in Kharkiv. The Soviet Union gained control over the entire territory of the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic east of the border with Poland.[9] In the Interbellum most of the territory of today's Western Ukraine belonged to the Second Polish Republic. Territories such as Bukovina and Carpatho-Ukraine belonged to Romania and Czechoslovakia, respectively.

At the onset of Operation Barbarossa by Nazi Germany, the region became part of the Third Reich in 1941. The southern half of West Ukraine was incorporated into the semi-colonial Distrikt Galizien (District of Galicia) created on August 1, 1941 (Document No. 1997-PS of July 17, 1941 by Adolf Hitler) with headquarters in Chełm Lubelski, bordering district of General Government to the west. Its northern part (Volhynia) was assigned to the Reichskommissariat Ukraine formed in September 1941. Notably, the District of Galicia was a separate administrative unit from the actual Reichskommissariat Ukraine with capital in Rivne. They were not connected with each other politically.[10] Bukovina was controlled by the pro-Nazi Kingdom of Romania. After the defeat of Germany in World War II, in May 1945 the Soviet Union incorporated all territories of current Western Ukraine into the Ukrainian SSR.[9]

Western Ukraine includes such lands as Zakarpattia (Kárpátalja), Volyn, Halychyna (Prykarpattia, Pokuttia), Bukovyna, Polissia, and Podillia. Note that sometimes Khmelnytsky region is considered a part of the central Ukraine as it is mostly lies within the western Podillya.

The history of Western Ukraine is closely associated with the history of the following lands:

- Easternmost Bukovina, historical region of Central Europe in official use since 1775, controlled by Kingdom of Romania after World War I and mostly ceded to the USSR by the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947.

- Eastern Galicia (Ukrainian: Halychyna), once a small kingdom with Lodomeria (1914), province of the Austrian Empire until the dissolution of Austria-Hungary in 1918. See also: crownland of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

- Red Ruthenia since medieval times in the area known today as Eastern Galicia.

- West Ukrainian People's Republic declared in late 1918 until early 1919 and claiming half of Galicia with mostly Polish city dwellers (historical sense).

- Carpatho-Ukraine region within Czechoslovakia (1939) under Hungarian control until the Nazi occupation of Hungary in 1944.

- General Government of Galicia and Bukovina captured from Austria-Hungary during World War I.

- Ținutul Suceava (Kingdom of Romania)

- Volhynia, historic region straddling Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus to the north. The alternate name for the region today is Lodomeria after the city of Volodymyr-Volynsky. See also: Polish unofficial term Kresy (Borderlands, 1918–1939) that includes the West Belarus as well as Volhynia.

- Zakarpattia or Carpathian Ruthenia presently in the Zakarpattia Oblast of western Ukraine.

Administrative and historic divisions

| Administrative region | Area (km2) | Population (2001 Census) | Population Estimate (Jan 2012) | Overlaping 1918–1939 regions of the Second Polish Republic and others | 1931 Population (thousands) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chernivtsi Oblast | 8,097 | 922,817 | 905,264 | Kingdom of Romania (see map) | |

| Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast | 13,927 | 1,409,760 | 1,380,128 | Stanisławowskie | 1,480.3 |

| Khmelnytskyi Oblast | 20,629 | 1,430,775 | 1,320,171 | USSR since 1921 Treaty of Riga | |

| Lviv Oblast | 21,831 | 2,626,543 | 2,540,938 | Lwowskie (north/east) | (tot.) 3,126.3 |

| Rivne Oblast | 20,051 | 1,173,304 | 1,154,256 | Równe/Kostopol/Sarny counties | 593.7 |

| Ternopil Oblast | 13,824 | 1,142,416 | 1,080,431 | Tarnopolskie | 1,533.5 |

| Volyn Oblast | 20,144 | 1,060,694 | 1,038,598 | Wołyńskie (western half) | (tot.) 2,085.6 |

| Zakarpattia Oblast | 12,753 | 1,258,264 | 1,250,759 | Carpathian Ruthenia | |

| Total | 131,256 | 10,101,756 | 9,765,281 |

Cultural characteristics

Differences with rest of Ukraine

"Perhaps, if Ukraine did not have its western regions, with Lviv at the centre, it would be easy to turn the country into another Belarus. But Galichina (Halychyna) and Bukovina, which became part of Soviet Ukraine under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, brought to the country a rebellious and free spirit."

Andrey Kurkov in an opinion piece about Euromaidan on BBC News Online (28 January 2014)[11]

Ukrainian is the dominant language in the region. Back in the schools of the Ukrainian SSR learning Russian was mandatory; currently, in modern Ukraine, in schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction, classes in Russian and in other minority languages are offered.[4][12]

In terms of religion, the majority of adherents share the Byzantine Rite of Christianity as in the rest of Ukraine, but due to the region escaping the 1920s and 1930s Soviet persecution, a notably greater church adherence and belief in religion's role in society is present. Due to the complex post-independence religious confrontation of several church groups and their adherents, the historical influence played a key role in shaping the present loyalty of Western Ukraine's faithful. In Galician provinces, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church has the strongest following in the country, and the largest share of property and faithful. In the remaining regions: Volhynia, Bukovina and Transcarpathia the Orthodoxy is prevalent. Outside of Western Ukraine the greatest in terms of Church property, clergy, and according to some estimates, faithful, is the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). In the listed regions (and in particular among the Orthodox faithful in Galicia), this position is notably weaker, as the main rivals, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church - Kyiv Patriarchate and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, have a far greater influence.

Noticeable cultural differences in the region (compared with the rest of Ukraine especially Southern Ukraine and Eastern Ukraine) are more "negative views" on the Russian language[13][14] and on Joseph Stalin[15] and more "positive views" on Ukrainian nationalism.[16] Calculating the yes-votes as a percentage of the total electorate reveals that a higher percentage of all (possible) voters in Western Ukraine supported Ukrainian independence in the 1991 Ukrainian independence referendum than in the rest of the country.[17][18]

In a poll conducted by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in the first half of February 2014 0.7% of polled in West Ukraine believed "Ukraine and Russia must unite into a single state", nationwide this percentage was 12.5.[19]

During elections voters of Western oblasts (provinces) vote mostly for parties (Our Ukraine, Batkivshchyna)[20] and presidential candidates (Viktor Yuschenko, Yulia Tymoshenko) with a pro-Western and state reform platform.[21][22][23] Of the regions of Western Ukraine, Galicia tends to be the most pro-Western and pro-nationalist area. Volhynia's politics are similar, though not as nationalist or as pro-Western as Galicia's. Bukovina-Chernvisti's electoral politics are more mixed and tempered by the region's significant Romanian minority. Finally, Zakarpattia's electoral politics tend to more competitive, similar to a Central Ukrainian oblast. This is due to the region's distinct historical and cultural identity as well as the significant Hungarian and Romanian minorities. The United Centre party led by Mukacheve native Viktor Baloha fares well in

See also

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Western Ukraine. |

Notes and references

- ↑ Jan T. Gross (2002). "Western Ukraine". Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine. Princeton University Press. pp. 48 / 99 / 114. ISBN 0691096031. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ↑ Myron Weiner, Sharon Stanton Russell (June 1, 2001). "Western Ukraine". Demography and National Security. Berghahn Books. pp. 313 / 322. ISBN 157181339X. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ↑ Philipp Ther, Ana Siljak (2001). "Forced Migration from Poland's Former Eastern Territories". Redrawing Nations. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 136–. ISBN 0742510948. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Serhy Yekelchyk Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation, Oxford University Press (2007), ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3

- ↑ Alfred J. Rieber (2013). Forced Migration in Central and Eastern Europe, 1939-1950. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 1135274827. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ↑ Rudolph Joseph Rummel (1996). Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocides and Mass Murders Since 1917 (Google Books preview). Transaction Publishers. p. 129. ISBN 1412827507. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ↑ Norman Davies (2005), "Part 2. Rossiya: The Russian Partition", God's Playground. A History of Poland: Volume II: 1795 to the Present, Oxford University Press, pp. 60–82, ISBN 0199253404, retrieved January 27, 2014

- ↑ David Crowley, National Style and Nation-state: Design in Poland from the Vernacular Revival to the International Style (Google Print), Manchester University Press ND, 1992, p. 12, ISBN 0-7190-3727-1

- 1 2 Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States: 1999, Routledge, 1999, ISBN 1857430581 (page 849)

- ↑ Arne Bewersdorf. "Hans-Adolf Asbach. Eine Nachkriegskarriere" (PDF). Band 19 Essay 5 (in German). Demokratische Geschichte. pp. 1–42. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Viewpoint: Ukrainian writer Andrey Kurkov on the protests, BBC News (28 January 2014)

- ↑ The Educational System of Ukraine, Nordic Recognition Network, April 2009.

- ↑ The language question, the results of recent research in 2012, RATING (25 May 2012)

- ↑ http://www.kyivpost.com/content/ukraine/poll-over-half-of-ukrainians-against-granting-official-status-to-russian-language-318212.html

- ↑ (Ukrainian) Ставлення населення України до постаті Йосипа Сталіна Attitude population Ukraine to the figure of Joseph Stalin, Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (1 March 2013)

- ↑ Who’s Afraid of Ukrainian History? by Timothy D. Snyder, The New York Review of Books (21 September 2010)

- ↑ Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith by Andrew Wilson, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521574579 (page 128)

- ↑ Ivan Katchanovski. (2009). Terrorists or National Heroes? Politics of the OUN and the UPA in Ukraine Paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Conference of the Canadian Political Science Association, Montreal, June 1–3, 2010

- ↑ How relations between Ukraine and Russia should look like? Public opinion polls’ results, Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (4 March 2014)

- ↑ Центральна виборча комісія України - WWW відображення ІАС "Вибори народних депутатів України 2012"

CEC substitues Tymoshenko, Lutsenko in voting papers - ↑ Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe by Uwe Backes and Patrick Moreau, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-36912-8 (page 396)

- ↑ Ukraine right-wing politics: is the genie out of the bottle?, openDemocracy.net (3 January 2011)

- ↑ Eight Reasons Why Ukraine’s Party of Regions Will Win the 2012 Elections by Taras Kuzio, The Jamestown Foundation (17 October 2012)

UKRAINE: Yushchenko needs Tymoshenko as ally again by Taras Kuzio, Oxford Analytica (5 October 2007)

Coordinates: 49°54′36″N 27°07′48″E / 49.9100°N 27.1300°E