William Stacy

| William Stacy | |

|---|---|

| Born |

February 15, 1734 Gloucester, Massachusetts |

| Died |

August 1802 (aged 68) Marietta, Ohio |

| Place of burial | Mound Cemetery (Marietta, Ohio) |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | Continental Army |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

| Relations |

Sarah Day, 1754-1790 Hannah Sheffield, 1790-1802 |

| Other work | pioneer to the Ohio Country |

William Stacy (February 15, 1734 – August 1802) was an officer of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and a pioneer to the Ohio Country. Published histories describe Colonel William Stacy's involvement in a variety of events during the war, such as rallying the militia on a village common in Massachusetts, participating in the Siege of Boston, being captured by Loyalists and American Indians at the Cherry Valley massacre, narrowly escaping a death by burning at the stake, General George Washington's efforts to obtain Stacy's release from captivity, and Washington's gift of a gold snuff box to Stacy at the end of the war.

During Col. William Stacy's post-war life, he was a pioneer, helping to establish Marietta, Ohio as the first permanent American settlement of the new United States in the Northwest Territory. He was active in the Marietta pioneer community, and served as foreman of the first Grand Jury in the Northwest Territory, an event establishing the rule of law in the territory. At the age of 56, he ice skated thirty miles up a frozen river, warning two of his sons of a possible Indian attack, which occurred several days later as the Big Bottom massacre and marked the beginning of the Northwest Indian War.

William Stacy's surname has also been spelled as Stacey, Stacia, and Stacie; the correct spelling is Stacy. He is often referred to as Colonel Stacy, an abbreviation of his last rank of lieutenant colonel.

Early life

William Stacy was born in Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1734 and died in Marietta, Ohio in 1802.[1] Slightly different years of birth and death have been reported.[2] Stacy grew up in Gloucester on the coast of Massachusetts and worked as a shoemaker, a trade learned from his father; he may also have worked in the seafaring business. William Stacy married Sarah Day in 1754. Subsequently, during 1757, they moved away from the coast to New Salem in western Massachusetts, and raised a large family. Stacy took up farming and continued his work as a shoemaker. He also became a commercial banker, loaning money at interest before there were any banks in the area. His customers were from New Salem and other towns in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. By the time of his early middle age, William Stacy was living a comfortable life; he was successful and widely known.[3] During 1775, at the age of 41, William Stacy's life changed with the onset of friction between the Thirteen Colonies and the British Empire.

Opening days of the Revolutionary War

William Stacy was an active revolutionary from the beginning of the American Revolutionary War. By one account, he entered service on April 19, 1775,[4] the day of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and the opening day of the war. Another account has William Stacy rallying the militia at his home village of New Salem, in the western portion of the colony, on April 20, 1775 upon receiving the news of Lexington and Concord.[5] A memorial plaque was dedicated to Colonel Stacy in 1956 on the village common of New Salem.[6][7][8] The story reflected on the plaque has been handed down for generations beginning with an early history in 1841,[5][9] and was included in the publication of the New Salem Sesquicentennial Committee in 1904.[10] The inscription on the plaque reads:

| “ | Alarm bells called the citizens to this green April 20, 1775 to learn of the battle at Lexington. There was indecision until 1st Lt. Stacy stepped forward and said "Fellow soldiers, I don't know how it is with you, but for me I will no longer serve a king that murders my own countrymen." Pulling out his commission from the crown he tore it to bits and trod it underfoot. Amid wild cheers a militia company of patriots was formed and under the gallant Stacy as Captain marched off to Cambridge. May such patriotism ever be with us.[6][7] | ” |

The New Salem Bicentennial Commission and town historian later speculated that this event might have occurred earlier, at the time of the Powder Alarm during 1774.[11] The Powder Alarm was a precursor to the events at Lexington and Concord.

Battle of Bunker Hill

As the war began, William Stacy served as major in Colonel Benjamin Woodbridge's regiment of Minutemen, which was organized into Woodbridge's (25th) Regiment.[4] During the Siege of Boston, Woodbridge's regiment was based at Cambridge, Massachusetts, near Boston, and participated in the Battle of Bunker Hill, the first large-scale battle of the war.[12] An orderly book shows that on June 13, 1775, several days before the battle, Major Stacy was officer of the night guard, while Colonel William Prescott, who would be the primary leader of patriot forces during the battle, was officer of the day.[13] Stacy was recommended for commission on June 16, the day before the battle.[4] On June 17, 1775, Woodbridge's regiment of 300 soldiers arrived at Bunker Hill and took up positions immediately prior to the battle,[12] and parts of the regiment engaged. A portion of Woodbridge's regiment joined Colonel Prescott's regiment at the redoubt and breastwork on the hill, and a company from Woodbridge's regiment deployed on the right flank.[14]

The defenders on the right flank fought valiantly from behind what cover they could find.[15] The men at the redoubt and breastwork fought until they had no more bullets, finally fighting with the butts of their guns, rocks, and their bare hands.[16] Woodbridge's regiment "was not commissioned, and there are few details of it, or of its officers, in the accounts of the battle."[17] Stacy's disposition is unknown. He later signed an affidavit regarding the guns of a fellow patriot who was killed in action at Bunker Hill.[18] Sergeant Benjamin Haskell (Haskall), also of New Salem and also a co-signer of that same affidavit, was reportedly in the center of the action near General Joseph Warren when Warren was killed during the battle.[10] The New Salem Sesquicentennial Committee paid homage to Stacy, Haskell, and others of that village, proclaiming:

And in those days of darkness and disaster, which, as they come to all nations, will surely again come to us, he will tell us of another Jeremiah Meacham, of more Jeremiah Ballards, of another Benjamin Haskell, of another William Stacy...[19]

Cherry Valley massacre, and prisoner of war

Stacy served as lieutenant colonel in Colonel Ichabod Alden's 7th Massachusetts Regiment during 1777 and 1778.[20] The regiment was sent to Cherry Valley, New York to protect the local population from Loyalists and American Indians. The Loyalists were organized as Butler's Rangers, a Loyalist militia in the British Army, led by Colonel John Butler and his son, Captain Walter Butler. The Loyalists operated together with American Indians, including some who were under the leadership of Joseph Brant, a Mohawk leader also known as Thayendanegea.[21]

While serving with Colonel Alden at Cherry Valley during October 1778, William Stacy was transferred to the 4th Massachusetts Regiment,[22] though remaining with Colonel Alden. During that time period, Lieutenant William McKendry, a quartermaster in Colonel Alden's regiment, kept a journal with firsthand accounts of the actions at Cherry Valley. One of his lighter notes concerning Colonel Stacy was a journal entry for October 6, 1778: "Col. Stacy and Capt. Ballard had a horse race. Col. Stacy won the bet."[23] However, one month later, Cherry Valley suffered war.

In November 11, 1778 a mixed force of Loyalists, British soldiers, Mohawk and Seneca under the command of Walter Butler descended on Cherry Valley.[24][25] Colonel Alden had been warned of their approach, but had dismissed the warnings. He and his command staff, including Stacy, were stationed in a house some 400 yards (370 m) from the fort.[26] McKendry described the attack in his journal: "Immediately came on 442 Indians from the Five Nations, 200 Tories under the command of one Col. Butler and Capt. Brant; attacked headquarters; killed Col. Alden; took Col. Stacy prisoner; attacked Fort Alden; after three hours retreated without success of taking the fort."[27][28] McKendry identified the fatalities of the massacre as Colonel Alden, thirteen other soldiers, and thirty civilian inhabitants.

It became known as the Cherry Valley massacre and was noted as one of the most horrific frontier massacres of the Revolution.[29] Three months later, in his journal entry for February 12, 1779, McKendry describes receiving a report from an Indian of William Stacy in captivity; Stacy was apparently concerned to reassure his fellow soldiers: "the last he knew of Col. Stacy he was well and in good spirits, and told him not to mind it for it was only the fortune of war."[30]

Several accounts indicate that during the Cherry Valley massacre or thereafter, Colonel Stacy was stripped naked and tied to a stake, and was about to be tortured and killed, as was the ritual for enemy warriors, but was spared by Joseph Brant.[31][32][33][34][35][36] William Stacy was a Freemason; Joseph Brant was an educated American Indian, and had also become a Freemason. It is reported that Stacy made an appeal as one Freemason to another, thus saving his life. Colonel Stacy was subsequently taken to Fort Niagara, the Loyalist base in New York and held prisoner under Colonel Butler during the summer of 1779.[37] At Fort Niagara, Molly Brant, the sister of Joseph Brant, was hostile toward Stacy, and wanted Colonel Butler to return custody of Stacy to the Indians. She proclaimed dreams of her and the Indians using Stacy's head in an Indian football game. Colonel Butler placated Molly Brant with rum and protected his prisoner.[37] Subsequently, from late-1779 through mid-1782, Colonel Stacy was held prisoner at Fort Chambly near Montreal.[38]

As a ranking prisoner-of-war, Colonel Stacy was the subject of high-level correspondence and actions of General George Washington and other leaders of the Continental Army. During April 1780, General Lafayette, who fought with the Americans during the Revolution, hand-carried a letter from General William Heath to General Washington, describing a reported Loyalist and British strategy concerning Stacy. The strategy was to continue holding Colonel Stacy as a prisoner-of-war, and to use Stacy in a prisoner exchange, should Colonel Butler or another ranking Loyalist officer, Sir John Johnson, be captured by the Continental Army.[39] During September 1780, General Washington attempted to arrange a prisoner exchange for Colonel Stacy,[40] but was unsuccessful. On November 1, 1781, the General Assembly of Massachusetts passed a Resolve urging Governor John Hancock to encourage General Heath to pursue a prisoner exchange for Stacy.[41]

Colonel Stacy was not released from captivity until the end of the war, during August 1782.[38][42] General Washington reportedly gave Stacy a gold snuff box as a personal memento after the war.[43] William Stacy's nephew, Nathaniel Stacy, writes that his first memory of childhood was the return of Col. William Stacy to New Salem after the war.[44]

Marietta and the Ohio Country

During early 1788,[45][46][47] at about 54 years of age, William Stacy joined with other Revolutionary War officers as a pioneer to the Ohio Country, and was involved in establishing Marietta, Ohio at the confluence of the Ohio and Muskingum rivers as the first permanent American settlement in the Northwest Territory. Colonel Stacy joined this venture as a shareholder in the Ohio Company of Associates,[48][49] which was formed and led by Gen. Rufus Putnam and Gen. Benjamin Tupper. General Lafayette visited Marietta years later and described these pioneers and former officers: "They were the bravest of brave. Better men never lived."[50] George Washington commented "I know many of the settlers personally, and there never were men better calculated to promote the welfare of such a community."[51] Marietta is located in the county of Ohio bearing Washington's name.

During the settlement of the Ohio Country, two of Colonel Stacy's sons were with a small group of pioneers attempting to establish a settlement on some good potential farmland known as Big Bottom, upriver from Marietta on the Muskingum River. Colonel Stacy ice skated 30 miles (48 km) up the frozen river in late December 1790 and warned his sons about the danger of a possible Indian attack. His concerns were realized several days later on January 2, 1791 with the occurrence of the Big Bottom massacre, and the beginning of the Northwest Indian War. Twelve people were killed in the attack, including Stacy's son John. His son Philemon was taken captive and died later.[52][53][54][55][56]

William Stacy was a prominent and active member of the pioneer settlement of Marietta. He superintended the construction of a stockade known as Picketed Point to protect the settlers from Indians,[57] he was an officer in the militia, and he was an officer on the first board of police.[58] Additionally, he served as an officer of the township of Marietta, and he owned one of two hand mills in the settlement.[59][60] William Stacy was a member of the Society of the Cincinnati and an original member of the American Union Lodge No. 1 (Freemasons) at Marietta;[61][62] the name of this lodge was reportedly suggested by Benjamin Franklin, and the seal engraved by Paul Revere.[63] Stacy was honored with the position of foreman of the first Grand Jury in the Northwest Territory. This was an important event, as this court was the first establishment of civil and criminal law in the pioneer country.[64]

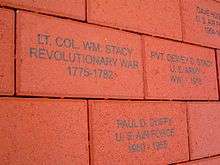

William Stacy lost his wife Sarah to smallpox during March 1790 after 36 years of marriage. He subsequently married Hannah Sheffield during July of that year. "A man highly esteemed for his many excellent qualities, and honored for his services and sufferings in the cause of freedom,"[65] William Stacy died in Marietta in 1802 at 68 years of age. He was buried in Marietta at Mound Cemetery,[66] the site of an ancient American Indian burial mound. Colonel Stacy has good company in his final resting place; Mound Cemetery reportedly contains the largest number of Revolutionary War officers buried in one location.[67] A new memorial marker was dedicated to William Stacy in 1928 in Mound Cemetery.

References

- ↑ Lemonds, Col. William Stacy, 13, 15, 61.

- ↑ Lemonds, Col. William Stacy, 61. (The William Stacy plaque in New Salem shows dates of 1733-1804, and the William Stacy marker in Marietta shows 1730-1802.)

- ↑ Lemonds, Col. William Stacy, 15-16.

- 1 2 3 Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors in the War of the Revolution, Vol 14, 796, 804-5.

- 1 2 Barber, Historical Collections...of Every Town in Massachusetts, 264–65.

- 1 2 Smithsonian American Art Museum, New Salem Lt. Col. William Stacy Monument, Smithsonian link at Stacy Monument.

- 1 2 Hunting, "Plaque Honoring William Stacy", Enterprise and Journal newspaper, October 4, 1956.

- ↑ Hunting, "Donor Attends Unveiling of Stacy Plaque", Enterprise and Journal newspaper, October 11, 1956.

- ↑ Blake, Anecdotes of the American Revolution, 200–02

- 1 2 New Salem Sesqui-Centennial and History of the Town, 21.

- ↑ Lemonds, Col. William Stacy, 99-100.

- 1 2 Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston, 136, 183.

- ↑ Frothingham, Battle-Field of Bunker Hill, 38–9.

- ↑ Ketchum, Decisive Day, 146.

- ↑ Ketchum, Decisive Day, 163.

- ↑ Ketchum, Decisive Day, 172–74.

- ↑ Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston, 183.

- ↑ Dean, New England Historical & Genealogical Register, 1895,Vol XLIX, 203-04.

- ↑ New Salem Sesqui-Centennial and History of the Town, 49.

- ↑ Heitman, Officers of the Continental Army, 38.

- ↑ Stone, Life of Joseph Brant, 372, 374, 386–87.

- ↑ Heitman, Officers of the Continental Army, 37, 513.

- ↑ Young, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. II – Second Series, 1855–1886, 449.

- ↑ Graymont, The Iroquois in the American Revolution, 184.

- ↑ Kelsay, Joseph Brant, 229.

- ↑ Barr, Unconquered: The Iroquois League at War in Colonial America, 153.

- ↑ Young, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. II – Second Series, 1855–1886, 449-50.

- ↑ Ketchum, History of Buffalo, 322. McKendry incorrectly placed John Butler and Joseph Brant in command of the force.

- ↑ Murray, Smithsonian Q & A: The American Revolution, 64.

- ↑ Young, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. II – Second Series, 1855–1886, 452.

- ↑ Barker, Recollections of the First Settlement of Ohio, 35.

- ↑ Beardsley, Reminiscences, 463.

- ↑ Hildreth, Early Pioneer Settlers of Ohio, 405-6.

- ↑ Moore, Masonic Review, Vol XI, 306-07.

- ↑ Drake, Memorials of the Society of Cincinnati, 465–67.

- ↑ Zimmer, "Colonel Stacy defies odds", Marietta Times, 21 March 1994.

- 1 2 Campbell, Annals of Tryon County; or, the Border Warfare of New-York during the Revolution, 110–11, 181-82.

- 1 2 McHenry, Rebel Prisoners at Quebec 1778-1783, 10, 34.

- ↑ Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Seventh Series, Vol. V., 60, 324.

- ↑ Sparks, Writings of George Washington, Vol VII, 211.

- ↑ Acts and Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (1890 edition), 789.

- ↑ Lemonds, Col. William Stacy, p. 27.

- ↑ History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts, Vol. II, 668.

- ↑ Stacy, Memoirs of the Life of Nathaniel Stacy, 24, 34.

- ↑ Hildreth, Pioneer History, 226.

- ↑ Edes and Darlington, Journal and Letters of Col. John May, 70–1.

- ↑ Zimmer, True Stories of Pioneer Times, 18.

- ↑ Hulbert, Proceedings of the Ohio Company, Volume I, xliv, cxxxi, 117, 131.

- ↑ Hulbert, Proceedings of the Ohio Company, Volume II, 2, 50, 56, 147, 202, 241.

- ↑ Cutler, Life and Times of Ephraim Cutler, 202–03.

- ↑ Sparks, Writings of George Washington, Vol IX, 385.

- ↑ Zimmer, More True Stories from Pioneer Valley, 92–101.

- ↑ Lane, Ode to the Big Bottom Massacre.

- ↑ Lemonds, Col. William Stacy, 47.

- ↑ Pritchard, "Area man discovers long roots", Marietta A.M. newspaper, July 24, 1994.

- ↑ Hildreth, Pioneer History, 434.

- ↑ Hildreth, Pioneer History, 326.

- ↑ Lemonds, Col. William Stacy, 37.

- ↑ Hildreth, Pioneer History, 273, 334.

- ↑ Summers, History of Marietta, 81.

- ↑ Summers, History of Marietta, 294–95.

- ↑ Lemonds, Col. William Stacy, pp. 57–8.

- ↑ Beach, A Pioneer College, 12.

- ↑ Hildreth, Pioneer History, 233.

- ↑ Andrews, History of Marietta and Washington County, Ohio, 879-80.

- ↑ Hawley, Mound Cemetery, 416.

- ↑ DAR, American Monthly, Vol. 16 (Jan-Jun 1900), 329.

Bibliography

- Acts and Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 1890 edition, Wright and Potter Printing Company, Boston (1890) p. 789.

- Andrews, Martin R.: History of Marietta and Washington County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, Biographical Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois (1902) pp. 879–80.

- Barber, John Warner: Historical Collections, being a General Collection of Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, etc., relating to the History and Antiquities of Every Town in Massachusetts, with Geographical Descriptions, Dorr, Howland, & Co., Worcester, Massachusetts (1841) chapter on Franklin County, section on New Salem, pp. 264–65. The 1844 edition of this historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Historical Collections of Massachusetts.

- Barber, John Warner: Historical Collections of the State of New York, containing a General Collection of the Most Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, etc., relating to its History and Antiquities, with Geographical Descriptions of Every Township in the State, S. Tuttle, New York (1842) pp. 442–43. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Historical Collections of New York.

- Barker, Joseph: Recollections of the First Settlement of Ohio, Marietta College, Marietta, Ohio (1958) p. 35; original manuscript written late in Joseph Barker's life, prior to his death in 1843.

- Barr, Daniel (2006). Unconquered: the Iroquois League at War in Colonial America. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98466-3. OCLC 260132653.

- Beach, Arthur: A Pioneer College: The Story of Marietta, John F. Cuneo Co., Marietta, Ohio (1935) p. 12.

- Beardsley, Levi: Reminiscences; Personal and Other Incidents; Early Settlement of Otsego County, Charles Vinten, New York (1852) p. 463. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Early Settlement of Otsego County.

- Blake, John Lauris: Anecdotes of the American Revolution, Alexander V. Blake, New York (1845) pp. 200–02.

- Bradford, Alden: History of Massachusetts, From 1764, to July, 1775: When General Washington took Command of the American Army, Richardson and Lord, Boston (1822) Chapter XVI (including the Bunker Hill Battle), pp. 382–83. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at History of Massachusetts.

- Campbell, William W.: Annals of Tryon County; or, the Border Warfare of New-York during the Revolution, J. & J. Harper, New York (1831) pp. 110–11, 182. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Annals of Tryon County.

- Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Seventh Series, Vol. V., Boston (1905) pp. 60, 324. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

- Cruikshank, Ernest: Butler's Rangers and the Settlement of Niagara, Tribune Printing House, Welland, Ontario, Canada (1893) p. 58. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Butler’s Rangers.

- Cutler, Julia Perkins: Life and Times of Ephraim Cutler, Robert Clarke and Co., Cincinnati, Ohio (1890) pp. 23–4, 202–03. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Life and Times of Ephraim Cutler.

- Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR): American Monthly, Vol. 16, Jan-Jun 1900, R. R. Bowker Co., New York (1900) p. 329 (re/Mound Cemetery).

- Dean, John Ward (Editor): The New England Historical & Genealogical Register, 1895,Vol XLIX, Boston (1895) in the section entitled 'Captain William Meacham at Bunker Hill,' p. 203-04.

- Drake, Francis S.: Memorials of the Society of Cincinnati of Massachusetts, Boston (1873) pp. 465–67. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Memorials of the Society of Cincinnati.

- Edes, Richard S. and Darlington, William M.: Journal and Letters of Col. John May, Robert Clarke and Co, Cincinnati, Ohio (1873), pp. 70–1. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Journal and Letters of Col. John May.

- Frothingham, Jr., Richard: History of the Siege of Boston and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, Second Edition, published by Charles C. Little and James Brown, Boston (1851) Chapters V and VII, regarding the Bunker Hill Battle, p. 136 (re/Woodbridge's regiment) and p. 183 (re/Stacy). This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Siege of Boston.

- Frothingham, Jr., Richard: The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill, a paper communicated to the Massachusetts Historical Society, June 10, 1875, Boston (1876) in a section regarding 'Extracts from an Orderly Book,' pp. 38–9. This historical paper is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Battle Field of Bunker Hill.

- Graymont, Barbara (1972). The Iroquois in the American Revolution. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-0083-6.

- Harvey, Arthur: Transactions of the Canadian Institute, Vol. IV 1892–93, Copp, Clark Company, Toronto (1895) pp. 288, 291. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Transactions of the Canadian Institute.

- Hawley, Owen: Mound Cemetery, Marietta, Ohio, Washington County Historical Society, Marietta, Ohio (1996).

- Heitman, Francis B.: Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution, Rare Book Shop Publishing Co., Washington, D.C. (1914) pp. 36–38, 514. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Officers of the Continental Army.

- Hildreth, S. P.: Biographical and Historical Memoirs of the Early Pioneer Settlers of Ohio, H. W. Derby and Co., Cincinnati, Ohio (1852) pp. 401–7.

- Hildreth, S. P.: Pioneer History: Being an Account of the First Examinations of the Ohio Valley, and the Early Settlement of the Northwest Territory, H. W. Derby and Co., Cincinnati, Ohio (1848) pp. 226, 233, 273, 326–27, 333–34, 432–34, 439. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Early Settlement of the Northwest Territory.

- History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts, Vol. II, Louis H. Everts, Philadelphia (1879) chapter on New Salem, section on Revolutionary Reminiscences, p. 668. (This book erroneously reports that Col. Stacy was killed by Indians near Marietta, Ohio; it was actually Col. Stacy's son John who was killed by Indians at Big Bottom near Marietta.)

- Holland, Josiah Gilbert: History of Western Massachusetts, the Counties of Hampden, Hampshire, Franklin, and Berkshire, Vol. I-Parts I and II, Samuel Bowles and Company, Springfield, Massachusetts (1855) Chapter XV, p. 214. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at History of Western Massachusetts.

- Hulbert, Archer Butler: The Records of the Original Proceedings of the Ohio Company, Volume I, Marietta Historical Commission, Marietta, Ohio (1917) pp. xliv, cxxxi, 117, 131. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Ohio Company, Volume I.

- Hulbert, Archer Butler: The Records of the Original Proceedings of the Ohio Company, Volume II, Marietta Historical Commission, Marietta, Ohio (1917) pp. 2, 50, 56, 147, 202, 241. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Ohio Company, Volume II.

- Hunting, Beatrice Fay: "Plaque Honoring William Stacy to be Uncovered Tomorrow at New Salem", Enterprise and Journal newspaper, Orange, Massachusetts (October 4, 1956).

- Hunting, Beatrice Fay: "Donor Attends Unveiling of Stacy Plaque at New Salem", Enterprise and Journal newspaper, Orange, Massachusetts (October 11, 1956).

- Kelsay, Isabel Thompson (1986). Joseph Brant, 1743–1807, Man of Two Worlds. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0208-8. OCLC 13823422.

- Ketchum, Richard M.: Decisive Day, the Battle for Bunker Hill, Henry Holt and Company, Owl Books Edition, New York (1999). ISBN 0-8050-6099-5

- Ketchum, William: An Authentic and Comprehensive History of Buffalo, with some account of Its Early Inhabitants both Savage and Civilized, Rockwell, Baker, and Hill, Buffalo, New York (1864) p. 322. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at History of Buffalo.

- Lane, Eula Rogers: Ode to the Big Bottom Massacre, Richardson Printing, Marietta, Ohio (1975).

- Lemonds, Leo L.: Col. William Stacy – Revolutionary War Hero, Cornhusker Press, Hastings, Nebraska (1993). ISBN 0-933909-09-8

- Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors in the War of the Revolution, Vol 14, online database, The Generations Network Inc., Provo, Utah (1998); original data from the Secretary of the Commonwealth, Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors in the War of the Revolution, Vol. 14, Wright and Potter Printing Co., Boston (1896), pp. 796 (William Stacey), 804-5 (William Stacy).

- McHenry, Chris: Rebel Prisoners at Quebec 1778-1783, Being a List of American Prisoners Held by the British during the Revolutionary War, Lawrenceburg, Indiana (1981).

- Moore, C.: The Masonic Review, Volume XI, C. Moore, Cincinnati, Ohio (1854) pp. 306–07.

- Moore, Frank: Diary of the American Revolution from Newspapers and Original Documents, Vol II, Charles Scribner, New York (1860), pp. 104–05. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at American Revolution from Original Documents.

- Murray, Stuart A. P.: Smithsonian Q & A: The American Revolution, HarperCollins Publishers by Hydra Publishing, New York (2006) p. 64.

- New Salem Sesqui-Centennial and History of the Town 1903, Athol, Massachusetts (1904) pp. 21, 49. (This book erroneously reports that Col. Stacy was killed by Indians near Marietta, Ohio; it was actually Col. Stacy's son John who was killed by Indians at Big Bottom near Marietta.) This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at New Salem Sesquicentennial.

- Pritchard, Joan: "Area man discovers long roots", Marietta A.M. newspaper, Parkersburg, West Virginia (July 24, 1994) p. 1., including article text, photo, and photo caption.

- Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York, Vol. IV, James B. Lyon, Albany, New York (1900) pp. 286, 292–93. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Public Papers of George Clinton.

- Sparks, Jared: The Writings of George Washington, Vol. VII, Harper and Brothers, New York (1847) p. 211. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at George Washington Vol VII.

- Sparks, Jared: The Writings of George Washington, Vol. IX, Harper and Brothers, New York (1847) p. 385. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at George Washington Vol. IX.

- Stacy, Nathaniel: Memoirs of the Life of Nathaniel Stacy, Abner Vedder, Columbus, Pennsylvania (1850) pp. 24, 34.

- Stone, William L.: Life of Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea) including the Border Wars of the American Revolution, J. Munsell, Albany, New York (1865) pp. 372, 374, 386–87. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Life of Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea).

- Summers, Thomas J.: History of Marietta, The Leader Publishing Co., Marietta, Ohio (1903) pp. 81, 100–02, 294–95. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at History of Marietta.

- Swett, S.: History of Bunker Hill Battle, With a Plan, Second Edition, Munroe and Francis, Boston (1826) 'Preliminary Chapter' p. 5 (re/Stacy), and chapter 'The Battle' p. 30 (re/Woodbridge's regiment). This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at History of Bunker Hill Battle.

- Young, Edward J.: Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. II – Second Series, 1855–1886, University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1886) section entitled Journal of William McKendry, pp. 436–78. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

- Zimmer, Louise: "Colonel Stacy defies odds of survival", Marietta Times newspaper, Marietta, Ohio (March 21, 1994) p. B5.

- Zimmer, Louise: More True Stories from Pioneer Valley, published by Sugden Book Store, Marietta, Ohio (1993) chapter 10 entitled Massacre at Big Bottom, pp. 92–101.

- Zimmer, Louise: True Stories of Pioneer Times, published by Broughton Foods company, Marietta, Ohio (1987) chapter 4 entitled The First Families p. 18.

External links

- William Stacy monument Smithsonian American Art Museum, Inventories of American Painting and Sculpture

- William Stacy biographic sketch Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati, in collaboration with the New England Historic Genealogical Society