Willie Brown (politician)

| Willie Brown | |

|---|---|

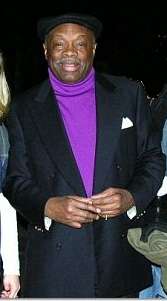

Brown in February 2006 | |

| 41st Mayor of San Francisco | |

|

In office January 8, 1996 – January 8, 2004 | |

| Preceded by | Frank Jordan |

| Succeeded by | Gavin Newsom |

| 58th Speaker of the California State Assembly | |

|

In office December 2, 1980 – June 5, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Leo McCarthy |

| Succeeded by | Doris Allen |

| Member of the California State Assembly from District 13 | |

|

In office 1992–1995 | |

| Member of the California State Assembly from District 17 | |

|

In office 1974–1992 | |

| Member of the California State Assembly from District 18 | |

|

In office 1965–1974 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Willie Lewis Brown, Jr. March 20, 1934 Mineola, Texas |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Blanche Vitero, separated |

| Residence | San Francisco, California |

| Alma mater | San Francisco State University University of California, Hastings |

| Profession | Attorney |

| Religion | Methodist |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | United States Army National Guard |

| Unit | Reserves |

Willie Lewis Brown, Jr. (born March 20, 1934) is an American politician of the Democratic Party. He served over 30 years in the California State Assembly, spending 15 years as its speaker, and later served as the 41st mayor of San Francisco, the first African American to do so. Under the current California term-limits law, no Speaker of the California State Assembly will be permitted to have a longer tenure than Brown's.[1] The San Francisco Chronicle called Brown "one of San Francisco's most notable mayors" who had "celebrity beyond the city's boundaries."[2]

Brown was born in Mineola, Texas and graduated from Mineola Colored High School in 1951.[3] He moved to San Francisco in 1951, attending San Francisco State University and graduating in 1955 with a degree in liberal studies.[4] Brown earned a J.D. from University of California, Hastings College of the Law in 1958. He spent several years in private practice before gaining election in his second attempt to the California Assembly in 1964. Brown became the Democrats' whip in 1969 and speaker in 1980. He was known for his ability to manage people and maintain party discipline. According to The New York Times, Brown became one of the country's most powerful state legislators.[5] His long tenure and powerful position were used as a focal point of California's initiative campaign to limit the terms of state legislators, which passed in 1990. During the last of his three allowed post-initiative terms, Brown maintained control of the Assembly despite a slim Republican majority by gaining the vote of several Republicans. Near the end of his final term, Brown left the legislature to become mayor of San Francisco.

Brown served as San Francisco mayor from January 8, 1996 until January 8, 2004. His tenure as mayor is marked by a significant increase in real estate development, public works, city beautification, and other large-scale city projects. He presided over the "dot-com" era at a time when San Francisco's economy was rapidly expanding. Brown presided over the city’s most diverse administration with more Asian Americans, women, Latinos, gays, and African Americans than his predecessors.[2] He increased San Francisco's funding of Muni by tens of millions of dollars and ended the city's policy of punishing people for feeding the homeless.

The SF Board of Supervisors opposed Brown's agenda and some of his initiatives, in particular office and housing development.[6] Brown was restricted by term limits from running for mayor and was succeeded by a political protege, Gavin Newsom. After being "termed out" of the mayor's office, Brown officially retired from politics, although he had often been associated with former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who served for seven years after the end of Brown's Mayoral tenure,[7][8] and continues to participate in fundraising for and advising other politicians.[9]

Early life

Brown was born in Mineola, a small segregated town in east Texas marked by racial tensions,[10] to Minnie Collins Boyd and Lewis Brown. Brown was the fourth of five children.[11] During Brown's childhood, mob violence periodically erupted in Mineola, keeping African Americans from voting. His first job was as a shoeshine boy in a whites-only barber shop.[11] He later worked as a janitor, fry cook, and field hand.[12] He learned his work ethic at a young age from his grandmother.[11] He graduated from MacFarland High School, an all-black school he later described as substandard, and left for San Francisco in August 1951 at the age of 17 to live with his uncle.

Brown originally wanted to attend Stanford University. His interviewer from Stanford also taught at San Francisco State and was surprised by Brown’s ambition. Brown did not meet the qualifications for San Francisco State, but the professor got him enrolled on probation.[11] Brown adjusted to college studies after working especially hard to catch up in his first semester.[13] He joined the Young Democrats and became friends with John L. Burton.[11] Brown originally wanted to be a math instructor but campus politics changed his ambitions. He became active in his church and the San Francisco NAACP. Brown worked as a doorman, janitor and shoe salesman to pay for college. Brown is a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.[13] He also joined the ROTC. Brown earned a bachelor's degree in political science from San Francisco State College in 1955.[14] Brown later stated that his decision to go to law school was "more upon the avoidance of military service than anything else." He quit the ROTC and joined the National Guard reserve where he was trained as a dental hygienist. Brown attended Hastings College of the Law where he also worked as a janitor to pay for law school. Brown befriended future San Francisco Mayor George Moscone for whom Brown would later manage a campaign.[13] Brown earned a J.D. in 1958 and was class president at Hastings.

In September 1958, Brown married Blanche Vitero, with whom he had three children, Susan, Robin, and Michael. He has four grandchildren, Besia, Matea, Mateo, and Lordes, and a step-granddaughter, Tyler. The couple separated in approximately 1976 but remain married. He has a daughter, Sydney Brown, by political fund raiser Carolyn Carpeneti.[15]

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Brown was one of a few African Americans practicing law in San Francisco when he opened his own practice.[11] He practiced criminal defense law, representing pimps, prostitutes, and other clients that more prominent attorneys would not represent.[11] One early case was to defend Mario Savio on his first civil disobedience arrest. He quickly became involved in the Civil Rights Movement, leading a well-orchestrated sit-in to protest housing discrimination after a local real estate office refused to work with him because of his race.[12] Brown helped organize the public protest and helped attract media coverage. His role in the protests gave him the notoriety to run for the Assembly.

Brown began his first run for the Assembly by having local African American ministers pass around a hat, collecting US$700.[11] He lost the election to the California State Assembly in 1962 by 600 votes before winning a second election in 1964.[12]

California State Assembly

.jpg)

Brown was one of four African Americans in the Assembly in 1964. He continued to be reelected to the Assembly until 1995. In the 1960s, Brown served as the Chair of the Legislative Representation Committee, a powerful Assembly position that helped Brown climb the Assembly ranks.[4] He became the Democrats' Assembly whip in 1969.[4] Brown also served on the Assembly Ways and Means Committee.[16] In 1972, he delivered a speech at the Democratic National Convention. He lost his bid for the speakership in 1972. In 1975, Willie Brown authored and lobbied the successful passing of the Consenting Adult Sex Bill that legalized homosexuality in California, thus earning the strong and lasting support of San Francisco's gay community. Similarly, he voted against AB 607, which banned same-sex marriage in 1977, further building his reputation as a supporter of the civil rights of gays and lesbians. During the 1970s, Brown continued to expand his legal practice, including the representation of several major real estate developers. He won the Speakership in 1980 with 28 Republican and 23 Democratic votes.

Brown was California's first African American Speaker of the Assembly, and served in the office from 1981 to 1995. In 1990, Brown helped negotiate an end to a 64-day budget standoff. In 1994, Brown gained the vote of a few Republicans to maintain the Speakership when the Democrats lost control of the Assembly to the Republicans led by Jim Brulte. Brown regained control in 1995 by making a deal with Republican defectors Doris Allen and Brian Setencich, both of whom were elected Speaker by the Democratic minority.[17] During their tenures, Brown was the de facto Speaker. During the 1990s, Brown dated Kamala Harris, then an Alameda County Deputy District Attorney. There was speculation the two would marry, but Brown broke up with her shortly after being elected Mayor of San Francisco.[18]

Brown's long service in the Assembly and political connections, his strong negotiation skills, and the Assembly's tenure system for leadership appointments, combined to give Brown nearly complete control over the California Legislature by the time he became Assembly Speaker. According to The New York Times, Brown became one of the country's most powerful state legislators.[5] He nicknamed himself the "Ayatollah of the Assembly".[19]

Brown was extremely popular in his home of San Francisco, though less so in the rest of the state.[20] Nevertheless, he wielded great control over statewide legislative affairs and political appointments, making it difficult for his conservative opponents to assail his power. Partially to remove Brown from his leadership position, a state constitutional amendment initiative was proposed and passed by the electorate in 1990, imposing term limits on state legislators.[6][21] Brown became the focus of the initiative. Brown raised just under US$1 million to defeat the initiative.[22] The California Legislature challenged the law but it was upheld by the courts.[22][23] California Proposition 140 also cut the legislature's staff budget by 30 percent, causing Brown to reduce legislative staff by at least 600.[22] After term limits forced Brown out of office, the Assembly re-structured its rules to give most of the powers formerly held by the Speaker to a leadership committee made up of senior members of both major parties.

Brown gained a reputation for knowing what was occurring in the state legislature at all times.[24] In 1992, he gave US$1.18 million to the Democratic Party to help with voter registration and several campaigns, some of which was from contributions from tobacco companies and insurance companies. As Speaker, he worked to defeat the Three Strikes Law. Critics have claimed Brown did not do enough to raise the legislature’s ethical standards or to protect the environment.[11] During his time in Sacramento, Brown estimates he raised close to US$75 million to help elect and reelect state Democrats.[25]

Brown led efforts in the Assembly for state universities to divest from South Africa and to increase AIDS research funding. Brown helped attain state funds for San Francisco, including funding for public health and mental health funds. Brown held the 1992 state budget for 63 days until Governor Pete Wilson added another US$1.1 billion for public schools.[11]

Brown had a reputation in the Assembly for his ability to manage people. Brown attained the vote of Doris Allen by treating her with the respect she thought she deserved. Republican State Senator Ken Maddy of Fresno noted Brown’s ability to “size up the situation and create, sometimes on the spot, a winning strategy.” According to Hobson, "He was a brilliant day care operator. ... He knew exactly how to hold the hand of his Assembly members. He dominated California politics like no other politician in the history of the state".[11]

Peoples Temple investigation

From 1975 to 1978, Brown supported the Peoples Temple, led by Jim Jones, while it was being investigated for alleged criminal wrongdoing. Brown attended the Temple perhaps a dozen times and served as master of ceremonies at a testimonial dinner for Jones where he stated in his introduction "[l]et me present to you a combination of Martin King, Angela Davis, Albert Einstein ... Chairman Mao."[26][27][28] Brown later said "If we knew then he was mad, clearly we wouldn't have appeared with him."[29]

Mayor of San Francisco

In 1995, Brown ran for Mayor of San Francisco. In his announcement speech, Brown said San Francisco needed a "resurrection" and that he would bring the "risk-taking leadership" the city needed.[25] Brown placed first in the first round of voting, but because no candidate received 50 percent of the vote, he ran against incumbent Frank Jordan in the December runoff. Brown gained the support of Supervisor Roberta Achtenberg who had placed third in the first round of voting. Brown campaigned on working to address poverty and problems with Muni. He called Jordan the "inept bumbler" and criticized his leadership. Jordan criticized Brown for his relations with special interests during his time in the State Assembly.[5] Brown easily defeated Jordan in the runoff.

Brown's inaugural celebration included an open invitation party with 10,000 attendees and local restaurants providing 10,000 meals to the homeless.[2][30] President Bill Clinton called Brown to congratulate him, and the congratulations were broadcast to the crowd. He delivered his inaugural address without notes and led the orchestra in “Stars and Stripes Forever". He arrived at the event in a horse-drawn carriage.[2] According to the New York Times, Brown was one of the nation’s few liberal big city mayors when he was elected in 1996.

In 1996, more than two thirds of San Franciscans approved of Brown's job performance.[31] As mayor, Brown made several appearances on national talk shows.[2] Brown called for expansions to the San Francisco budget to provide for new employees and programs. In 1999, Brown proposed hiring 1,392 new city workers and proposed a second straight budget with a US$100 million surplus. He helped to oversee the settling of a two-day garbage strike in April 1997.[24] During Brown's tenure, San Francisco’s budget increased to US$5.2 billion and the city added 4,000 new employees. Brown tried to develop a plan for universal health care, but there wasn’t enough in the budget to do so.[2] Brown put in long days as mayor, scheduling days of solid meetings and, at times, conducting two meetings at the same time.[24] Brown opened City Hall on Saturdays to answer questions.[19] He would later claim of his mayorship that he helped restore the city’s spirit and pride.[24]

Brown's opponents in his 1999 mayoral reelection campaign were former Mayor Frank Jordan and Clint Reilly. They criticized Brown for spending the city's US$1 billion in budget growth without addressing the city's major problems and creating an environment in city hall of corruption and patronage.[24] Tom Ammiano was a late write-in candidate and he faced Brown in the runoff election. Brown won reelection by a 20 percent margin. He was supported by most major developers and business interests. Ammiano campaigned on a promise that he would raise the minimum wage to US$11 per hour and scrutinize corporate business taxes. Brown repeatedly claimed that Ammiano would raise taxes. President Clinton recorded a telephone message on Brown's behalf. Brown's campaign spent US$3.1 million to Ammiano's US$300,000.[32] The 1999 mayoral race was the subject of the documentary See How They Run.[33]

Crime and public safety

Although scheduled on a flight to New York City the day of the September 11, 2001 attacks, Brown received an alert from his SFO security detail and cancelled. After learning of the attacks, he ordered the city to close schools and courts, concerned over the potential for terrorist attacks in the city, and recommended to representatives of the Bank of America Tower and Transamerica Pyramid that they should also close.[34]

In February 2003, Brown's appointed Police Chief, Earl Sanders, and several top officials at the San Francisco Police Department were arrested for conspiring to obstruct the police investigation into an incident involving off-duty officers that was popularly called "Fajitagate".[2]

Social policy

Brown ended San Francisco's policy of punishing people for feeding the homeless. San Francisco continued to enforce its policy regarding the conduct of the homeless in public places.[35] In 1998, Brown supported forcibly removing homeless people from Golden Gate Park and police crackdowns on the homeless for drunkenness, urinating, defecating, or sleeping on the sidewalk. Brown introduced job training programs and a $11 million drug treatment program. San Francisco, then the United States' 13th largest city, had the nation's third largest homeless population at a peak of 16,000.[31] In November 1997, he requested nighttime helicopter searches in Golden Gate Park.[2] The Brown administration spent hundreds of millions of dollars creating new shelters, supportive housing, and drug treatment centers to address homelessness, but these measures did not end San Francisco’s problem with homelessness.[2]

In 1996, Brown approved the Equal Benefits Ordinance that required city contractors to provide domestic partner benefits to their employees.[2] In 1998, Brown wrote a letter to President Clinton urging him to halt a federal lawsuit aimed at closing medical marijuana clubs.[36]

Transportation

Mass transit

One of Brown's central campaign promises was his "100-Day Plan for Muni," in which he boasted he would fix the city's municipal bus system in that many days.[24] Brown supported the "Peer Pressure" Bus Patrol program, which paid former gang members and troubled youth to patrol Muni buses. Brown claimed the program helped reduce crime.[37] He fired Muni chief Phil Adams and replaced him with his chief of staff Emilio Cruz. In 1998, Brown was Mayor during the summer of the Muni meltdown as Muni implemented the new ATC system and Brown promised riders there would be better times ahead. A voter approved initiative in the following year would help improve Muni services. Brown increased Muni's budget by tens of millions of dollars over his tenure.[2] Brown later said he made a mistake in over promising with his 100-Day Plan.[24]

Brown helped mediate a settlement to the 1997 BART strike.[24]

During his first term as mayor, Brown quietly favored the demolition and abolition of the Transbay Terminal[38] to accommodate the redevelopment of the site for market-rate housing. Centrally located at First and Mission Streets near the Financial District and South Beach, the terminal originally served as the San Francisco terminus for the electric commuter trains of the East Bay Electric Lines, the Key System of streetcars and the Sacramento Northern railroads which ran on the lower deck of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. Following the termination of streetcar service in 1958, the terminal has seen continuous service as a major bus facility for East Bay commuters; AC Transit buses transport riders from the terminal directly into neighborhoods throughout the inner East Bay. The terminal also serves passengers traveling to San Mateo County and the North Bay aboard SamTrans and Golden Gate Transit buses respectively, and to tourists arriving by bus motorcoach. Today, the terminal is being planned for redevelopment as a region wide mass transit hub maintaining the current bus services, but with a new tunnel that would extend the Caltrain commuter rail line from its current terminus at Fourth and Townsend Streets to the site. Once completed, Caltrain riders would no longer need to transfer to Muni in order to reach the downtown financial district. Additionally, the heavy rail portion of the terminal would be designed to accommodate the planned High Speed Rail lines to Los Angeles.

In 1998, The Berkeley, California-based Bicycle Civil Liberties Union, produced a two-hour documentary film in the muckraker journalism tradition, July 25th: The Secret is Out, which gives evidence of Brown's designs for the Transbay Terminal site.

Critical Mass

Since 1992, cyclists riding in San Francisco's monthly Critical Mass bicycle rides had used the "corking" technique at street intersections to block rush-hour cross-traffic.[39][40][41][42] In 1997, Brown approved San Francisco Police Department Chief Fred Lau's plan to conduct a crackdown on the rides,[43] calling them "a terrible demonstration of intolerance".[44] and "an incredible display of arrogance."[45] Brown said after arrests were made when a Critical Mass event became violent "I think we ought to confiscate their bicycles"[46] and that "a little jail time" would teach Critical Mass riders a lesson.[47] On the night of the July 25, 1997 ride 115 riders were arrested for unlawful assembly, jailed, and had their bicycles confiscated by the police.[48][49] By 2002, Brown and the city's relations with Critical Mass had changed. On the 10th anniversary of Critical Mass on September 27, 2002, the city officially closed down four blocks to automobile traffic for the annual Car-Free Day Street Fair. Brown remarked concerning the event: "I'm delighted. A new tradition has been born in our city."[50]

Urban planning and development

As San Francisco mayor, Brown was criticized for aggregating power, and for favoring certain business interests at the expense of the city as a whole. Supporters point to the many development projects completed or planned under his watch, including the restoration of City Hall and historic waterfront buildings; the setting in motion of one of the city's largest ever mixed use development projects in Mission Bay, and the development of a second campus for the University of California, San Francisco. In contrast, critics objected to the construction of many live-work loft buildings in formerly working-class neighborhoods that they believed lead to gentrification and displacement of residents and light industry.[51]

Under Brown, San Francisco's city hall was restored from damages sustained during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Brown insisted on restoring the light courts and having the dome gilded with more than US$400,000 in real gold. The Embarcadero was redeveloped and the Mission Bay Development project began. Brown also oversaw the approval of the Catellus Development Corp., US$100 million restoration of the century-old Ferry Building, the new Asian Art Museum, the new M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, the expansion of the Moscone Convention Center and San Francisco International Airport's new international terminal.[2] Brown worked to restructure the Housing Authority.[24] Brown helped established an AFL-CIO housing trust to build affordable housing and he worked to increase the city’s share of federal and state grants. He oversaw declining crime rates and improvements in the city’s economy, finances, and credit ratings during his first term.[24]

Brown was known for his shrewd and strategic use of the details of the planning process to affect and facilitate development projects on his watch. In regards to a parking garage on Vallejo Street desired by North Beach and Chinatown merchants, Brown circumvented neighborhood resident opponents of the garage by ordering demolition of the site's existing structure to commence on a Friday night and be done by Monday morning, when the group was certain to try to obtain a restraining order. "It was with the demolition permit I outsmarted them," Brown recounts proudly, claiming that as the critics rushed toward court, "someone shouted out to them that the building had disappeared over the weekend. They've never recovered from that little maneuver."[52]

During his time as Mayor, Brown hoped to build a new stadium for the San Francisco 49ers and worked with the 49ers to create a plan.[24] No new facility was built for the team during his tenure.[53] Brown worked with the San Francisco Giants to build a new stadium in the China Basin after previous stadium measures had failed on the ballot.[2] The stadium gained approval by San Francisco voters in 1996 and opened in 2000.[24]

Due to vacancies on the Board of Supervisors prior to 2000, Brown was able to appoint 8 of the 11 members of the board. Due to a change in San Francisco's election laws that took effect in 2000, the board changed from at-large to district based elections, and all seats on the board were up for election. The voters elected a new group of supervisors that ran on changing the city’s development policy. Voters also passed a measure that weakened the mayor's control over the Planning Commission and Board of Appeals. The new majority limited Brown's power over the Elections Department, the Police Commission, and extending San Francisco International Airport's runways into the bay to reduce flight delays.[2] In July 2001, the Board of Supervisors overrode Brown’s veto for the first time, creating legislation that created the new home ownership option of tenancies in common.

Favoritism and patronage criticisms, FBI investigations

Allegations of political patronage followed Brown from the State Legislature through his tenure as San Francisco mayor. Former Los Angeles County GOP Assemblyman Paul Horcher, who voted in 1994 to keep Brown as Speaker, was reassigned to a position with a six-figure salary as head San Francisco's solid waste management program. Brian Setencich also was appointed to a position by Brown.[24] Both were hired as special assistants after losing their assembly seats because of their support of Brown. Former San Francisco Supervisor Bill Maher was also hired as a special assistant after campaigning for Brown in his first mayoral race.[54] Brown is also criticized for favoritism to Ms. Carpeneti, the lobbyist with whom he had a child. In 1998 Brown arranged for Carpeneti to obtain a rent-free office in the city-owned Bill Graham Civic Auditorium. Between then and 2003, a period that spans the birth of their daughter, Carpeneti was paid an estimated $2.33 million by nonprofit groups and political committees controlled by then Mayor Brown and his friends.[15][55]

Brown increased the city's special assistants payroll from US$15.6 to US$45.6 million between 1995 and 2001.[56] Between April 29, 2001 and May 3, 2001, San Francisco Chronicle reporters Lance Williams and Chuck Finnie released a five-part story concerning Brown and his relations with city contractors, lobbyists, and city appointments and hires he had made during his tenure as Mayor. The report concluded that there was an appearance of favoritism and conflicts of interest in the awarding of city contracts and development deals, a perception that large contracts had an undue influence on city hall, and patronage with the hiring of campaign workers, contributors, legislative colleagues, and friends to government positions.[57]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation investigated Brown when he was Speaker. One investigation was a sting operation concerning a fake fish company attempting to bribe Brown; he was not charged with any criminal act. The FBI further investigated Brown from 1998 to 2003 over his appointees at the Airport Commission for potential conflicts of interests. Brown friend, contributor, and former law client, Charlie Walker was given a share of city contracts. He had served jail time in 1984 for violating laws concerning minority contracting. The FBI also investigated Brown's approval of expansion of Sutro Tower and SFO. Scott Company, with one prominent Brown backer, was accused of using a phony minority front company to secure an airport construction project. Robert Nurisso was sentenced to house arrest. During Brown's administration, there were two convictions of city officials tied to Brown.

The FBI investigated Brown's friend Charlie Walker, who won several city contracts. Walker had previously thrown several parties for Brown and was among his biggest fund raisers.[24] Brown reassigned Parking and Traffic chief Bill Maher to an airport job when his critics claimed Maher should have been fired.[24] Brown put his former girlfriend, Wendy Linka, on the city payroll.[2] Brown was known for his strong loyalty to his supporters.

Retinitis pigmentosa

While serving as Assembly Speaker, Brown was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP), a disease that still has no cure and that would slowly steal his eyesight. RP is a hereditary disease that causes a continual loss of peripheral vision and often leads to total blindness. Brown's two sisters were also diagnosed with RP. Brown remarked, "Having RP is a challenge, as Speaker of the Assembly it was very important that I recognize people in the halls of the Legislature. But I couldn't see people unless they were right in front of me. I needed to have the security people give me notes to tell me who was in the room. Reading is also very difficult so I use larger print notes and memos. Living with RP means having to use more of your brain function—I listen more intently, I memorize vast amounts of information, and I have trained my computer to recognize numerous verbal commands."[58] Brown has worked with the Foundation Fighting Blindness to raise awareness of the disease.

Aesthetic style

Brown has had an ostentatious sense of personal style from the beginning that he later parlayed into a political advantage. Even in high school he was fastidious about his appearance.[18] In office he became famous for British and Italian suits, sports cars, nightclubbing, and a collection of dressy hats.[59] He was once called "The Best Dressed Man in San Francisco" by Esquire magazine.[60]

In his 2008 autobiography, Basic Brown, he described his taste for US$6,000 Brioni suits and his search for the perfect chocolate Corvette to add to his car collection. In one chapter titled: "The Power of Clothes: Don't Pull a Dukakis", Brown explains that men should acquire a navy blazer for each season: one with "a hint of green" for springtime, another with more autumnal threading for the fall.[61] He further remarks, "You really shouldn't try to get through a public day wearing just one thing. ... Sometimes, I change clothes four times a day."[62]

Brown in the media

As Mayor of San Francisco, Brown was often portrayed mockingly but affectionately by political cartoonists and columnists as a vain emperor, presiding in a robe and crown over the inconsequential kingdom of San Francisco.[63] He enjoyed the attention this brought to his personal life, disarming friends and critics with humor that directed attention away from the policy agendas he was pursuing.[64]

Brown's flamboyant style made him so well known as the consummate politician that when an actor playing a party politician in 1990's The Godfather Part III did not understand director Francis Ford Coppola's instruction to model his character after Brown, Coppola fired the actor and hired Brown himself to play the role. Brown later appeared in 2000's Just One Night as a judge. He also played himself in two Disney films, George of the Jungle and The Princess Diaries, and the 2003 Universal release Hulk as the mayor of San Francisco. He appeared as himself, alongside Geraldo Rivera, in an episode of Nash Bridges. He also made a cameo appearance in the 1984 Jefferson Starship music video Layin' It on the Line (depicting a futuristic 1988 presidential campaign).

Brown was criticized in 1996 for his comments that 49ers backup quarterback Elvis Grbac was "an embarrassment to humankind." He was criticized in 1997 for responding to Golden State Warriors player Latrell Sprewell choking his coach P. J. Carlesimo by saying, "his boss may have needed choking."[24]

In 1998, Brown contacted the Japanese television cooking competition Iron Chef, suggesting San Franciscan Chef Ron Siegel to battle one of the Iron Chefs. Brown appeared on the telecast himself, enthusiastically promoting the Chef. Siegel won the battle, in a rare clean sweep against Iron Chef Hiroyuki Sakai.

Brown remained neutral throughout the 2008 presidential campaign. Brown has been working in recent years as a radio talk show host and as a pundit on local and national political television shows and is seen as attempting to build credibility by abstaining from endorsing candidates for office. "I've never been high on endorsements," Brown said. "When you get one, all it does is keep the other guy from getting one. Really, what did getting John Kerry's endorsement do to help Barack Obama?"[65]

After mayorship

After leaving the mayor's office, Brown considered running for the State Senate but ultimately declined.[66] From January 2006 through September 2006, Brown hosted a morning radio show with comedian Will Durst on a local San Francisco Air America Radio affiliate. He also makes a weekly podcast. Brown established The Willie L. Brown, Jr. Institute on Politics & Public Service, an unaffiliated nonprofit organization at San Francisco State University.[6] The center trains students for careers in municipal, county and regional governments. The center will be one of the first to focus on local government in the country. Brown gave the center's library a collection of his artifacts, videotapes and legislative papers from his 40 years in public office. He is also planning to mentor students, teach a course on leadership, and recruit guest speakers.[6]

On February 5, 2008, Simon & Schuster released Brown's hardcover autobiography, Basic Brown: My Life and Our Times, with collaborator P. J. Corkery. The book release coincided with California's Democratic Presidential Primary on the same day. On July 20, 2008, Brown began writing a column for the San Francisco Chronicle, a move that has drawn the ire of some Chronicle staffmembers and ethicists for the failure to disclose the multiple conflicts of interest Brown has.[67]

In 2009, Brown was defending general construction contractor Monica Ung, 49 of Alamo, California. Accused of flouting labor laws and defrauding immigrant construction workers of their wages from laboring on Oakland municipal construction projects, Ung was arraigned for dozens of felony fraud charges on 24 August 2009 in Alameda County Superior Court. Brown's decision to defend Ung angered many in the East Bay's labor community.[68]

In September 2013, the western span of the Bay Bridge was officially named for Willie Brown.[69] In early 2015, Brown was named to the board of directors of the San Francisco-based biopharmaceutical company Global Blood Therapeutics.[70]

Transportation company

In late 2012, Brown became the regulatory lawyer for Wingz, a ride-sharing service.[71][72] In that capacity, Brown represented the company before the California Public Utilities Commission, which was creating new regulations to legalize the ability of Transportation Network Companies to operate ridesharing services in California.[71][72][73]

References

- ↑ "California's G.O.P. Finally Elects an Assembly Speaker It Can Call Its Own". The New York Times. January 7, 1996. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Gordon, Rachel (January 4, 2004). "THE MAYOR'S LEGACY: WILLIE BROWN 'Da Mayor' soared during tenure that rivals city's most notable, but some critical goals not met". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ↑ "Reunions". www.addieemcfarland.org. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

- 1 2 3 "Willie Brown". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2006-11-21. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- 1 2 3 B. Drummond Ayres JR. (December 12, 1995). "After Rave Reviews, San Francisco Mayoral Race Is Ending Run". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Rachel Gordon (November 8, 2007). "San Francisco Willie Brown comes home to roost at S.F. State Ex-mayor sets up leadership center at alma mater". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ Anthony York (2006-12-31). "Why Arnold invited Willie Brown". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Julia Cheever (6 June 2006). "California Governor says build the fence". San Francisco Sentinel. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ↑ "California Democratic Party Lines Up Behind pro-Bush anti-Labor Schwarzenegger". Indybay. 2006-10-13. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ In 1930s, the "tensions" were undoubtedly less than they would have been than if anyone had attempted to enforce integration.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Clarence Johnson (October 24, 1995). "PAGE ONE – It's Brown vs. Brown Ex-speaker's reputation helps, hinders him". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- 1 2 3 Gregory Lewis (October 1997). "Running the Show: Mayor Willie Brown's Life Of Public Service". Black Collegian. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- 1 2 3 James Richardson (Winter 1996–1997). "The Higher Education of Mayor Willie Brown". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. CH II Publishers: 106–109. JSTOR 2962848.

- ↑ SFSU Public Affairs Press Release, May 28, 2001, "San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown challenges SFSU Class of 2001", accessed July 4, 2007

- 1 2 Lance Williams; Patrick Hoge (13 July 2007). "Love and Money, Mayor's fund-raiser got millions". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ↑ EGregory Lewis. "Running the Show Mayor Willie Brown's Life Of Public Service". The Black Collegian Magazine, IMDiversity, INC. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ↑ Daniel Weintraub (1 July 1995). "Keeping the grip on power". State Legislatures. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- 1 2 Richardson, James (1997). Willie Brown: A Biography. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-585-24985-7.

- 1 2 Evelyn Nieves (December 1, 1998). "San Franciscans Tire of the Life of the Party". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ Gregory Lewis (October 1997). "Running the show: Mayor Willie Brown's life of public service". The Black Collegian. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Anthony York (23 June 1999). "Is black politics dead in California?". Salon. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- 1 2 3 Katherine Bishop (24 January 1991). "Political Giants Deflated in California". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- ↑ "State Legislative Term Limits". U.S. Term Limits. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Edward Epstein (September 14, 1999). "The Many Faces Of Willie Brown Grand approach wins fans, foes". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- 1 2 B. Drummond Ayres Jr. (June 4, 1995). "It's Official: Willie Brown Runs for Mayor". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ Tim Reiterman (1982) "Raven: The Untold Story of The Rev. Jim Jones and His People" ISBN 0-525-24136-1 page 308

- ↑ Nancy Dooley & Tim Reiterman, "Jim Jones: Power Broker", San Francisco Examiner, August 7, 1977

- ↑ Layton, Deborah. Seductive Poison. Anchor, 1999. ISBN 0-385-48984-6. p. 105.

- ↑ Rick Ross (2000-02). "The Jonestown Massacre". Cult Education and Recovery. Retrieved 2008-05-18. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ MICHAEL J. YBARRA (January 9, 1996). "San Francisco Journal; A Time To Rejoice In Mantle Of Power". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- 1 2 Evelyn Nieves (November 13, 1998). "Homelessness Tests San Francisco's Ideals". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ Evelyn Nieves (December 16, 1999). "San Francisco Mayor Easily Wins Another Term". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ Curiel, Jonathan (2002-09-06). "Nasty race for mayor is film winner". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ Phillip Matier; Andrew Ross (September 12, 2001). "Willie Brown got low-key early warning about air travel". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ Carey Goldberg (May 20, 1996). "Homeless in San Francisco: A New Policy". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ "Four California Mayors Ask Clinton to Stop Marijuana Club Suit". The New York Times. March 22, 1998. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ "'Peer Pressure' Bus Patrol Is Called Successful in San Francisco". The New York Times. February 15, 1998. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ Edward Epstein; Chronicle Staff Writer (26 October 1998). "Mayors Get on the Train; Leaders promote ballot measures in 4 cities for Bay Bridge rail line". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- ↑ Martin, Glen (1997-07-26). "Cycling Event at Critical Point, Commuters vent, mayor gets tough, riders dismayed". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Leslie Goldberg (March 23, 1997). "Bikers press for their right of way". San Francisco Examiner.

- ↑ David Colker (September 7, 1997). "In LA, Movement Lacks Critical Element—Bike Commuters". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Molly O'Donnell (December 1, 2004). "Critical Mass: Social Change on Two Wheels". Wiretap(AlterNet). Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ McCormick, Erin; Finnie, Chuck; Gordon, Rachel (1997-07-29). "Cops say group bike ride needs permit: Police distribute new policy, with mayor's blessing; supes look at plan to license cyclists". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ MacNeil/Lehrer News Hour (29 August 1997). "MacNeil/Lehrer News Hour Transcript". PBS Public Television.

- ↑ Edward Epstein (28 August 1997). "Bike Fiasco Points Up S.F. Mayor's Transit Errors: Brown has had trouble taming city's road rage". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Jim Herron Zamora; Chuck Finnie; Emily Gurnon (1997-07-27). "Brown: Take bikes of busted cyclists". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Steve Lopez (11 August 1997). "The Scariest Biker Gang Of Them All". Time.

- ↑ Chuck Finnie (23 July 1997). "Cycling protesters make deal with City: Critical Mass to temper havoc in exchange for talks". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ↑ Glen Martin; Henry K. Lee; Torri Minton; Manny Fernandez; Chronicle Staff Writers (1997-07-26). "S.F. Bike Chaos – 250 Arrests: 5,000 bikers snarl commute". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ "Critical Mass protestors celebrate 10th year". CNN. The Associated Press. 27 September 2002.

- ↑ Evelyn Nieves (8 January 2004). "Brown Leaves Office, No Longer Prince of the City". Washington Post.

- ↑ John King (4 March 2008). "Basic Brown' reveals a brazen mayor". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Tim Golden (November 24, 1996). "His Humble Pie Is Full of Chutzpah". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ Lance Williams; Chuck Finnie (30 April 2001). "Mayor's patronage army, Brown fattens payroll with loyalists, colleagues, friends". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ↑ Phillip Matier; Andrew Ross (19 January 2001). "Da Mayor, 66, Says He'll Be a Dad Again". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Lance Williams; Chuck Finnie (April 30, 2001). "Mayor's patronage army Brown fattens payroll with loyalists, colleagues, friends". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ Lance Williams; Chuck Finnie (May 3, 2001). "Brown's City Hall is politics as usual despite election New board has little effect, so far". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ Aubrey Patsika (2004-02-09). "A Strong Sense of Vision". Foundation Fighting Blindness, Blue Water Media, Inc., (202)861-0000, www.bluewatermedia.com. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- ↑ Richardson, James D. (1993). "Willie Brown: The Early Years". The AFP Reporter. 15 (4). Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ "The best dressed real men in America". Esquire. 1 September 2006.

- ↑ Matt Bai (10 February 2008). "Willie's World". New York Times Review of Books.

- ↑ Will Haper (13 February 2008). "Reader Quiz: Which Willie Brown Quotes Are Stranger Than Fiction?". San Francisco Weekly.

- ↑ Phil Frank. "Farley". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Rob Morse (October 27, 1996). "25 ways to suck up to Willie Brown". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Joe Garofoli (28 January 2008). "Some state politicians leery of endorsing" Check

|url=value (help). San Francisco Chronicle. - ↑ B. Drummond Ayres Jr. (March 10, 2002). "Political Briefing; He Left His Heart In Sacramento". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ http://articles.latimes.com/2006/dec/31/opinion/op-richardson31 San Francisco Weekly. July 30, 2008.

- ↑ Robert Gammon (26 August 2009). "Monica's Victims, a Chinatown construction magnate may have ripped off taxpayers and workers for as much as $20 million. Now she's trying to evict Le Cheval.". Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ↑ Kwong, Jessica. "Willie Brown says he's humbled by Bay Bridge naming honor". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ "Profile". People. Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 35 (4). 15 February 2015. p. 37.

- 1 2 Geoffrey Fowler (28 October 2012). "Taxi Apps Face Bumpy Road". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- 1 2 Tomio Geron; Forbes Staff (28 January 2013). "Tickengo's Willie Brown Wants Revenue Cap For Ride-Sharing Drivers". Forbes. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ↑ Benny Evangelista, San Francisco Chronicle Staff Writer (4 December 2012). "State PUC to hold hearings on new cab app laws". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

Bibliography

- Brown, Willie (2008). Basic Brown: My Life and Our Times. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-9081-X.

- Clucas, Richard A. (1994). The Speaker's Electoral Connection: Willie Brown and the California Assembly. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-87772-361-3.

- Green, Robert Lee (1974). Willie L. Brown, Jr: Daring Black Leader. Milwaukee: Franklin Publishers. OCLC 53358667.

- Richardson, James (1993). Willie Brown: The Early Years. Washington D.C.: Alicia Patterson Foundation. OCLC 28525812.

- Richardson, James (1997). Willie Brown: A Biography. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-585-24985-7.

External links

- Will & Willie podcast

- Willie Brown at the Internet Movie Database

- New York Times - Topics: Willie L Brown, Jr. collected news stories

- Biographer captures mayor in print SF Chronicle, October 14, 1996

- Mayor's patronage army SF Chronicle, April 30, 2001

- Gamed by the System: Wherein Willie Brown details his valiant attempts to conquer homelessness and bring Muni into submission SF Chronicle, January 20, 2008

| California Assembly | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Edward M. Gaffney |

California State Assemblyman, 18th District 1965–1974 |

Succeeded by Leo T. McCarthy |

| Preceded by John J. Miller |

California State Assemblyman, 17th District 1974–1992 |

Succeeded by Dean Andal |

| Preceded by Barbara Lee |

California State Assemblyman, 13th District 1992–1995 |

Succeeded by Carole Migden |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Frank Jordan |

Mayor of San Francisco 1996–2004 |

Succeeded by Gavin Newsom |