Sam'al

Archeological site of Sam'al | |

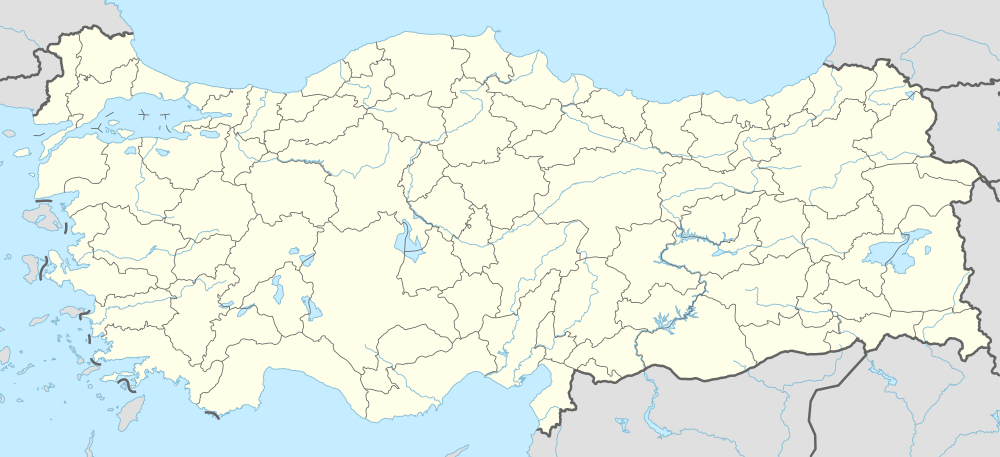

Shown within Turkey | |

| Location | Zincirli Höyük, Gaziantep Province, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Region | Anatolia |

| Coordinates | 37°06′13″N 36°40′43″E / 37.10361°N 36.67861°ECoordinates: 37°06′13″N 36°40′43″E / 37.10361°N 36.67861°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

Sam'al (Hittite: Yadiya) was founded as a Hittite colony from 1725-1200 BC. It became an Aramaean Principality,[1] following the collapse of the Hittite Empire in 1200 BC. In 940 BC it became a kingdom, and in 680 BC the state came under control of the Assyrian Empire. It was located at Zincirli Höyük in the Anti-Taurus Mountains of modern Turkey's Gaziantep Province.

History

The site of Sam'al was occupied in the Early Bronze Age, and became part of the kingdom of Yamhad (Aleppo) early in the second millennium. It was absorbed into the Hittite empire during the middle of that millennium. After the fall of the Hittites, it was controlled by the Neo-Hittites until the arrival of the Aramaeans established the city as the center of a kingdom called Sam'al. With the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Sam'al became a vassal state and later a province of that empire. This ended in the 7th century BC with the fall of the Assyrian Empire.

Kingdom of Sam'al

| Kingdom of Sam'al | ||||||||||||

| Principality/Kingdom | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Capital | Sam'al | |||||||||||

| Languages | Hittite Aramaic Akkadian | |||||||||||

| Political structure | Principality/Kingdom | |||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||

| • | Established | 1200 BC | ||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 609 BC | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Kingdom of Sam’al (in Aramaic Ya’idi) was a middle power of the Middle-East in the first half of the 1st millennium BC. It was near the Nur Mountains. Sam'al was the capital of the country. Royal steles and stone tablets from the period, of Kilamuva and Panamuva II, are the main sources for historical data about this timeperiod.

It became a middle power at the end of the 10th century BC. It had expanded from being a city state and gained territories from Carchemish, around Adana from Quwê and remained independent. It didn’t become part of Cilicia. In 859 BC Alimus was saved with the help of Hajja, king of Sam'al. He didn’t participate in the Battle of Qarqar in 853 BC, but Assyria had been blocked in the Western area. Though the campaign of Assyria in 825 BC occupied the vital territories of Sam'al, Quwê had been defeated, but it had been reorganised as Denyen. After the death of Shalmaneser III, Sam'al again became independent.

Some rulers of Sam'al had aggressive expansionist politics; others acceeded to one of the anti-Assyrian Syrian coalition. Assyrian sources are unreliable regarding Sam'al. Sam'al was one of Assyria’s satellite states in the calendars of Shalmaneser III. Though around 830 BC Azitawadda, king of Denyen, states Sam'al is his satellite country – at the same time, Kilamuwa mentions on his stela that he hired Assyria against Denyen. Other sources from the same period mention Sam'al as a satellite state of Denyen and Assyria wanted to occupy this territory. Kilamuva might offer for Deyen to be a satellite state. Before this, he should defeat his greatest foe, Azitawadda. Assyrians won over Denyen and Sam'al in 825 BC. Sam'al became independent after the death of Shalmaneser III.

There’s an alternative opinion which states Sam'al fought against Assyrians at Alimus in 859 BC, and in 853 BC it became a member of the Assyrian alliance. This makes clear why Shalmaneser III had listed Sam'al as a satellite state. The Kingdom of Sam'al would like to open a corridor between Assyria and Denyen. It was prevented by the unified Syrian forces. This unity had been dissolved in 825 BC. As a result Sam'al became a winner. After the death of Shalmanezer III, it became an independent state and Denyen couldn’t occupy it.

At the end, in 717 BC, Assyria occupied the country under the rule of Sargon II.

Archaeology

The site was excavated in 1888, 1890, 1890–91, 1894 and 1902 by a German Oriental Society expedition led by Felix von Luschan and Robert Koldewey.[2][3][4][5][6]

They found a heavily fortified teardrop-shaped citadel, which was surrounded by the as yet unexcavated town and a further enormous double fortification wall with three gates and 100 bastions. Among the notable objects found at the site are five giant statues of lions carved from stone, which apparently had guarded the gates of the city, but may have been ritually buried together within the citadel. The German excavations on the citadel recovered large numbers of relief-carved orthostats, along with inscriptions in Aramaic, Phoenician, and Akkadian. These are on exhibit in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin, and Istanbul. Also found was the notable Victory stele of Esarhaddon celebrating his victory over Taharqa. The field diaries of the excavation were lost during World War II.

In August 2006, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago began a new long-term excavation project at the site of Zincirli under the directorship of David Schloen. Four seasons of excavation have been conducted through 2009.[7]

Inscriptions

Three royal inscriptions from Ya'udi or Sam'al are particularly informative for the history of the area. The earliest is from the reign of King Panammu I, the others later at 730 BCE. The dialectical peculiarities of these royal inscriptions from Sam'al (Ya'udi) have led to some scholars including P.-E. Dion.[8] and S. Moscati[9] advancing "Samalian" or "Ya'udic" as a distinct variety of Old Aramaic.[10][11][12]

The stele of Kuttamuwa

Kuttamuwa was an 8th-century BC royal official from Sam'al who ordered an inscribed stele, that was to be erected upon his death. The inscription requested that his mourners commemorate his life and his afterlife with feasts "for my soul that is in this stele." It is one of the earliest references in a Near East culture to a soul as a separate entity from the body. The 800-pound basalt stele is three feet tall and two feet wide.[13]

Notes

- ↑ "Middle East Kingdoms/ Ancient Syria". 2014. The History Files. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ Felix von Luschan et al, Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli. vol. 1: Einleitung und Inschriften, Spemann, 1893

- ↑ Felix von Luschan and Carl Humann and Robert Koldewey, Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli. vol. 2: Ausgrabungsbericht und Architektur, Spemann, 1898

- ↑ Felix von Luschan, Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli. vol. 3: Thorsculpturen, Georg Reimer, 1902

- ↑ Felix von Luschan and Gustav Jacoby, Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli. vol. 4: Georg Reimer, 1911

- ↑ Felix von Luschan and Walter Andrae, Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli. vol. 5: Die Kleinfunde von Sendschirli, Walter de Gruyter, 1943

- ↑ J. David Schloen and Amir S. Fink, New Excavations at Zincirli Höyük in Turkey (Ancient Sam’al) and the Discovery of an Inscribed Mortuary Stele, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, vol. 356, pp. 1-13, November 2009

- ↑ P.-E. Dion, La langue de Ya'udi (Waterloo, Ontario 1974), in: RSO 53 (1979)

- ↑ Moscati 1964, S.—: An Introduction to the Comparative Grammar of the Semitic Languages, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden.

- ↑ Klaus Beyer The Aramaic Language, Its Distribution and Subdivisions 1986- Page 12 3525535732 "In addition the three "Ya'udic" royal inscriptions from Zinjirli in northern Syria (c. 825, 750, 730 B.C.) witness to early Ancient Aramaic: KAl 25, 214, 215; TSSI -, 13, 14; J.Friedrich, Phoni- zisch-punische Grammatik, Rome 1951, 153-162; ..."

- ↑ Angel Sáenz-Badillos, John Elwolde A History of the Hebrew Language 1996 0521556341 Page 35 "According to some scholars, after 1400 BCE the languages which would later develop into Ya'udic and Aramaic...."

- ↑ Joseph A. Fitzmyer A Wandering Armenian: Collected Aramaic Essays 1979 - Page 68 080284846X "This is partly because he refuses to see Ugaritic as Canaanite and partly because he prefers to treat so-called Ya^udic as distinct from Aramaic — if I understand him correctly.89 "

- ↑ "Found: An Ancient Monument to the Soul". New York Times. November 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

In a mountainous kingdom in what is now southeastern Turkey, there lived in the 8th century BC. a royal official, Kuttamuwa, who oversaw the completion of an inscribed stone monument, or stele, to be erected upon his death. The words instructed mourners to commemorate his life and afterlife with feasts “for my soul that is in this stele.”

See also

References

- Simon B. Parker (1996). "Appeals for military intervention: stories from Zinjirli and the Bible". The Biblical Archaeologist 59(4): 213-224.

- Ussishkin, David (1970). "The Syro-Hittite ritual burial of monuments". Journal of Near Eastern Studies 29(2): 124-128.

- Ralf-B Wartke, Sam’al: Ein aramäischer Stadtstaat des 10. bis 8. Jhs. v. Chr. und die Geschichte seiner Erforschung, Philipp von Zabern, 2005

- J. P. Francev, ed. (1967). Világtörténet tíz kötetben, I. kötet (in Hungarian). Kossuth K.

- U. Bahadir. Alkim, The Road from Samal to Asitawandawa: Contributions to the Historical Geography of the Amanus Region, Anadolu Arastirmalari, vol. 2, pp. 3–41, 1965

- Dennis Pardee, A New Aramaic Inscription from Zincirli, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, vol. 356, pp. 51–71, 2009

- David Schloen, J. and Amir S. Fink, Searching for Ancient Samal: New Excavations at Zincirli in Turkey, Near Eastern Archaeology, vol. 72/4, pp. 203–219, 2009

- Eudora J. Struble and Virginia Rimmer Herrmann, An Eternal Feast at Sam?al: The New Iron Age Mortuary Stele from Zincirli in Context, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, vol. 356, pp. 15–49, 2009

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sam'al. |

- Official Zincirli Excavation Website at www.uchicago.edu

- Plans and fotos at www.hittitemonuments.com

- Levy-White project to publish small finds from German excavations

- The Aramean Kingdoms of Sam'al