Étude Op. 10, No. 5 (Chopin)

Étude Op. 10, No. 5, in G-flat major, is a study for solo piano composed by Frédéric Chopin in 1830. It was first published in 1833 in France,[1] Germany,[2] and England[3] as the fifth piece of his Études Op. 10. This work is characterized by the rapid triplet figuration played by the right hand exclusively on black keys. This melodic figuration is accompanied by the left hand in staccato chords and octaves.

Significance

The so-called "Black Key Étude" is one of the most popular.[4] It has been a repertoire piece of pianists since Chopin’s time and has inspired numerous exercises, arrangements and paraphrases. Chopin himself did not believe the study to be his most interesting one. In a letter to his pianist friend and musical executor Julian Fontana he comments on Clara Wieck’s performance:

"Did Wieck play my Etude well? How could she have chosen precisely this Etude, the least interesting for those who do not know that it is intended for the black keys, instead of something better! It would have been better to remain silent."[5]

Von Bülow (1830 - 1894) speaks rather disdainfully of Op. 10, No. 5 as a "Damen-Salon Etüde" ("Ladies Salon Etude").[6]

Structure and stylistic traits

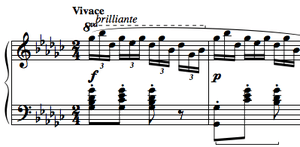

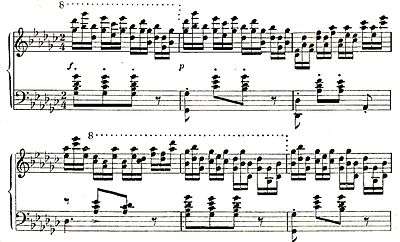

Like all of Chopin’s other études, this work is in ternary form A-B-A. The two eight-bar periods of the A section are characterized by frequent dynamic contrasts. Each reentry of the first bar, occurring every four bars, is marked by a forte, followed in the second bar by a piano restatement in a lower register. This capricious[7] opening in the tonic is replied by an upward movement and a syncopated accompaniment in the third and fourth bar. This pattern is repeated four times. The harmonic scheme of the A section is relatively simple, featuring tonic (first two bars) versus dominant (third and fourth bars), but the consequent of the first period shifts to B-flat major (poco rallentando, pp), while the consequent of the second one modulates to the dominant key D-flat major.

D-flat major is also the key of the middle section which is exactly twice as long as the A section. Its 32 bars though do not subdivide into four eight-bar periods but into sections of (4 + 2) + 4 + 2 +4 + 8 + 8 bars with six motivically distinct modifications of the original semiquaver triplet figure, thus offering an attractive break from the symmetry.[8] An effective dynamic increase begins in bar 23 but does not end in a climax as the crescendo does not lead to fortissimo but eases off in diminuendos (bars 36 and 40).[9] Harmonically the section (bars 23 - 41) may be interpreted as an extended and ornamented D-flat major cadence.[9] Musicologist Hugo Leichtentritt (1874–1951) compares the left hand of bars 33 - 48 to horn signals.[10] These "announce" the recapitulation of the A part which begins as a literal restatement in bar 49, seems to approach a climax and eases off with a sudden delicatissimo pianissimo smorzando passage, leading via a cadence to the coda. The coda consists of two periods, the last one stretched by three bars.[11] The first one is a restatement of the middle section’s opening transposed to the tonic G-flat major. The consequent of the second period contains a brilliantly swooshing, widely positioned arpeggio for both hands (bars 79 - 83) and is pianistically attractive. Its effect is based on the accent enforced by a third at the beginning of each triplet, as well as on the tenth and eleventh stretches of the left hand and the ascending bass line covering the entire range of the keyboard.[11] The piece ends with a rapid octave passage, ff and staccato, played by both hands on black keys, in a G-flat major pentatonic scale. Some prominent performers, including Horowitz and Rosenthal, choose to perform the final octave passage glissando.[12]

Black keys

Étude Op. 10, No. 5 is known as the Black Key Étude as its right-hand part is to be played entirely on black keys. Leichtentritt states that the melodic character resulting from the use of black keys is "based on the pentatonic scale to which the piece owes its strangely playful, attractively primitive tint."[11] He presents a melodic reduction of the right hand part which, played in octaves by piccolo and flute, resembles a frolicsome Scottish jig.[13]

The cadence to the coda (bar 66) contains the only white key, F-natural, to be played by the right hand. But in the original editions[14] the two thirds (G-flat - E-flat and D-flat - F) are placed on the left hand staff, though editors like Jan Ekier recommend them to be (partially) played by the right hand.[15]

Character

Chopin gave the tempo/character indications vivace (lively, vivid) and (in small print) brillante. German pianist and composer Theodor Kullak (1818–1882) says that the piece is "full of Polish elegance."[16] American music critic James Huneker (1857–1921) calls it "graceful, delicately witty, a trifle naughty, arch and roguish and […] delightfully invented."[16] Leichtentritt states "the piece shall glisten and sparkle, giggle and whisper, entice and flatter, have charming, occasionally coquettish, accents, bubble over with lively agility, enchant with amiable elegance"[17] and Chopin scholar Robert Collet believes that it "needs to be played with real gaiety and wit, though not without tenderness."[18]

Technical difficulties

In Schumann’s NZM article on Pianoforte-Études, NZM (1836),[19] the study is classified under the category "speed and lightness" (Schnelligkeit und Leichtigkeit). Huneker states "it requires smooth, velvet-tipped fingers and a supple wrist."[16] Chopin’s original indication concerning articulation of the right hand is legato. A sempre legatissimo indication is given at bar 33. Nevertheless Austrian pianist and composer Gottfried Galston (1879–1950) questions these indications and calls them "completely incomprehensible."[20] He argues for a "leggierissimo with tossed fingers" ("mit geworfenen Fingern") and is backed up in this opinion by Leichtentritt.[17] French pianist Alfred Cortot (1877–1962) modifies the legato indication and talks about a "brilliant and delicate legato—so-called ‘jeu perlé’ ["pearly" play]."[21] He believes the main difficulty, among others, to concern "suppleness while shifting the hand in order to facilitate even action of the fingers in disjunct positions."[22]

Preliminary exercises are given by both Galston and Cortot. Hungarian pianist and composer Rafael Joseffy (1852–1915) introduces exercises in his instructive edition[23] including numerous "octave-exercises on black keys."[24]

Paraphrases and arrangements

In the Studienbuch (1922) Galston published his complete arrangement in double notes.[25] Seven versions can be found in Leopold Godowsky’s 53 Studies on Chopin's Études.[26] They include a version for both hands reversed, a transposition to C major for the white keys, a Tarantella in A minor, a Capriccio "on the white and black keys," an inversion for the left hand, an inversion for the right hand and a version for the left hand alone. Besides these there is a combination of Op. 10, No. 5 and Op. 25, No. 9 ("Butterfly"), called Badinage (banter), which Canadian pianist Marc-André Hamelin calls a "brilliant jeu d’esprit" and a "fantastically clever feat of combinatorial wizardry."[27] German pianist Friedrich Wührer’s version[28] for both hands reversed resembles Godowsky’s first one.

Notes and references

- ↑ ("French edition"). Paris: M. Schlesinger, June 1833.

- ↑ ("German edition"). Leipzig: Fr. Kistner, August 1833 .

- ↑ ("English edition"). London: Wessel & Co, August 1833.

- ↑ Collet, Robert. "Studies, Preludes and Impromptus." In Frédéric Chopin: Profiles of the Man and the Musician. Ed. Alan Walker. London: Barrie & Rockliff, 1966, p. 131

- ↑ "F. Chopin to Julian Fontana in Paris, Marseilles 25 April 1839." see Ekier, Jan, ed. (National Edition). "About the Etudes." Chopin Etudes. Warsaw: Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1999.

- ↑ Huneker, James. "The Studies—Titanic Experiments." In Chopin: The Man and His Music. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1900, p. 61.

- ↑ Leichtentritt, Hugo. "Die Etüden." In Analyse der Chopin’schen Klavierwerke [Analysis of Chopin’s Piano Works]. Band II. Berlin: Max Hesses Verlag, 1922, p. 106.

- ↑ Leichtentritt, p. 106.

- 1 2 Leichtentritt, p. 107

- ↑ Leichtentritt, p. 108

- 1 2 3 Leichtentritt, p. 109

- ↑ Rosen, Charles: Piano Notes. New York: Free Press, 2002, page 85.

- ↑ Leichtentritt, pp. 110–111

- ↑ "French," "German" and "English" editions

- ↑ Ekier, Jan, ed. (National Edition). "Performance Commentary." Chopin Etudes. Warsaw: Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1999, p. 140.

- 1 2 3 Huneker, p. 61

- 1 2 Leichtentritt, p. 105

- ↑ Collet, p. 131

- ↑ Schumann, Robert. "Die Pianoforte-Etuden, ihren Zwecken nach geordnet" ["The Pianoforte Études, Categorized According to their Purposes"]. Neue Zeitschrift für Musik No.11, February 6, 1836, p.45.

- ↑ Galston, Gottfried. Studienbuch [Study Book]. III. Abend [3rd Recital] (Frédéric Chopin). Berlin: Bruno Cassirer, 1910, p. 20.

- ↑ Cortot, Alfred. Frédéric Chopin. 12 Études, op.10. Édition de travail des oeuvres de Chopin. Paris: Éditions Salabert, 1915, p. 33.

- ↑ Cortot, p. 33

- ↑ Joseffy, Rafael. Etudes for the Piano. Instructive Edition. New York: G. Schirmer, 1901

- ↑ Joseffy, p. 33

- ↑ Galston, pp. 25 - 31

- ↑ Godowsky, Leopold. Studien über die Etüden von Chopin. Berlin: Robert Lienau (vormals Schlesinger), 1903 - 1914.

- ↑ Hamelin, Marc-André. "Godowsky’s Studies on Chopin’s Etudes." Liner notes for Godowsky: The Complete Studies on Chopin’s Etudes. Hyperion. CDA67411/2, 2000, p. 26.

- ↑ Wührer, Friedrich. Achtzehn Studien zu Frederic Chopins Etuden [sic] [18 Studies on Chopin’s Etudes]. In Motu Contrario [In Contrary Motion]. Heidelberg: Willy Müller, Süddeutscher Musikverlag, 1958.

External links

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

- Analysis of Chopin Etudes at Chopin: the poet of the piano

- Études Op.10: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Sheet music available in .pdf or LilyPond format, from Mutopia.

- Étude Op. 10, No. 5 on YouTube played by Vladimir de Pachmann (1927: with commentary, mistakes and changes)

- Étude Op. 10, No. 5 on YouTube played by Ignaz Friedman (1928)

- Chopin/Godowsky Op.10 No.5: fourth version (Capriccio) on YouTube played by Marc-André Hamelin

- Chopin/Godowsky Op.10 No.5 combined with Op. 25 No. 9 (Badinage) on YouTube played by Marc-André Hamelin