Étude Op. 10, No. 3 (Chopin)

Étude Op. 10, No. 3, in E major, is a study for solo piano composed by Frédéric Chopin in 1832. It was first published in 1833 in France,[1] Germany,[2] and England[3] as the third piece of his Études Op. 10. This is a slow cantabile study for polyphonic and legato playing. Chopin himself believed the melody to be his most beautiful one.[4] It became famous through numerous popular arrangements. Although this étude is sometimes identified by the names "Tristesse" (Sadness) or "Farewell (L'Adieu)," neither is a name given by Chopin.

Significance

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

This étude differs from most of Chopin's in its tempo, its poetic character and the lingering yet powerful recitation of its cantabile melody. It marks a significant departure from the technical virtuosity required in standard études before Chopin's time, though, especially in the third volume of Clementi’s Gradus ad Parnassum (1826), slow études for polyphonic playing, especially slower introductions to études, as well as études with alternating slower and faster sections, can easily be found. According to German scholar and Chopin biographer Frederick Niecks (1845–1924) Chopin said to his German pupil and copyist Adolph Gutmann (1819–1882) that he "had never in his life written another such beautiful melody (‘chant’); and on one occasion when Gutmann was studying it the master lifted his arms with his hands clasped and exclaimed: ‘O, my fatherland!’ ("O, me [sic] patrie!")"[5] Niecks writes that this study "may be reckoned among Chopin’s loveliest compositions" as it "combines classical chasteness of contour with the fragrance of romanticism." American music critic James Huneker (1857–1921) believed it to be "simpler, less morbid, sultry and languorous, therefore saner, than the much bepraised study in C sharp minor."[6] Chopin originally gave his Op.10 No. 3 Etude the tempo Vivace, later adding ..ma non troppo. It is also relevant to observe that this etude is in 2/4 time and not 4/4, although it is generally performed as a very slow 4/8 piece. The visual impact of the score alone strongly suggests that a languid tempo is incorrect. There is also no doppio movimento following the opening section, which results in an erroneous drastic slowing down for the re-entry of the opening section. These are unwritten by Chopin, according to his autograph manuscript and other original source materials.

Structure and stylistic traits

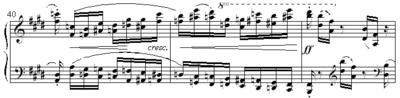

Like most of Chopin’s other études, this work is in ternary form (A-B-A). The A section is of remarkable melodic construction. Musicologist Hugo Leichtentritt (1874–1951) believes its asymmetric structure, (5 + 3) + (5 + 7) bars, to be highly relevant to the impact of the melody.[7][8] The first five bars can be seen as a contraction of 4 + 4 bars with the final clause (consequent) of the prototypal eight-bar period replaced by bar 5. Italian composer and editor Alfredo Casella (1883–1947) notices the Pelléas-like effect of the oscillating major thirds in bars 4/5 anticipating Debussy by more than half a century.[9] According to Leichtentritt bars 6 – 8 with its stretto and final ritenuto can be interpreted as the contraction of a four-bar clause. The melody is accompanied by oscillating semiquavers played by the right hand in a manner reminiscent of the Adagio cantabile movement of Beethoven’s Sonata Pathétique while the syncopated rhythm in the left hand somewhat counteracts the simple "naiveté" of this oscillation. The melody itself is characterized by repeated notes. A novelty are the distinct crescendo and diminuendo signs allocated "polyphonically" and sometimes even differing in the two voices played by the right hand.

In the middle section (poco più animato), characterized by rhythmic shifts and sudden harmonic turns, theme and accompaniment are fused into oscillating double notes. There are five eight-bar phrases. Leichtentritt observes that each eight-bar phrase is "ruled by a new motif" and that "each of these segments surpasses the preceding one in sonority and brilliancy."[10] The third period, although it stays chromatically centered around E major, is a long sequence of diminished seventh and tritone intervals, littered with accidentals and irregular rhythms difficult to play. It reaches a climax in the fourth period (bars 46 – 53), a bravura passage of double sixths for both hands. The fifth period (bars 54 – 61), leading back to the final restatement of the theme, can be described as an extended dominant seventh. Leichtentritt believes it to be "one of the most exquisite sound impressions ever contrived for the piano."[11] Its effect is "based on its contrast with the fourth period and on the gradation of the most tender nuances in piano." The final A section is a quite literal though shortened restatement of the first one. At the end of the étude the fair copy autograph contains the directive attacca il presto con fuoco which means that Chopin foresaw the joint performance of both this étude and the following one.[12]

This étude’s similarity to a nocturne is frequently noted. Leichtentritt calls the étude a "nocturne like piece of intimate and rich cantabile melodics [gesangreicher, inniger Melodik], relieved in its middle section by a highly effective sound-unfolding [Klangentfaltung] of a novel and peculiarly original character [Gepräge]."[13] German pianist and composer Theodor Kullak (1818–1882) called the study a "lovely poetic tone-piece".[14]

Tempo

Polish pianist and editor Jan Ekier (1913-2014) writes in the Performance Commentary to the Polish National Edition that this étude is "always performed slower or much slower than is indicated by [Chopin’s] tempo [MM 100]."[15] The original autograph (first draft) bears the marking Vivace changed to Vivace ma non troppo in the clean copy (Stichvorlage) for the French edition.[16] Ekier observes: "Only in print did Chopin change it to Lento ma non troppo simultaneously adding a metronome mark." The middle section, especially the bravura passage in sixths at the climax, is always played at a much faster tempo than the A section. An argument in favor of Chopin’s fast metronome mark, according to Ekier, is the fact that the middle section "has the marking poco più animato [not in bold print], which suggests only a slight acceleration of the opening tempo." This indication is not found in the autographs, showing that Chopin originally envisioned a fast and unified tempo for the étude. Chopin disliked excessive sentiments expressed during performance, as it tore the musical structure he initially intended. Chopin also eschewed a beleaguering tempo with distinct pulse since it destroyed the significance of the 2/4 time signature.[17]

Technical difficulties

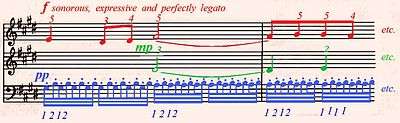

In Schumann’s NZM article on Pianoforte-Études, NZM (1836),[18] the study is classified under the category "melody and accompaniment in one hand simultaneously." As the right hand part contains a melody (and sometimes an extra filling voice) to be played by the three "weaker fingers" and an accompaniment figure played by the first two fingers, the hand can be divided into an "active element" and an "accompanying element" not unlike in the Étude Op. 10 No. 2. French pianist Alfred Cortot (1877–1962) especially mentions the importance of "polyphonic and legato playing," the "individual tone value of the fingers" and the "intense expressiveness imparted by the weaker fingers."[19]

Preparatory exercises consist of addressing two "distinct muscular areas" of the hand by playing two voices with one hand, each voice with a "different intensity in tone." Cortot believes that the "weight of the hand" should lean towards the fingers playing the predominant part while the others "remain limp." He recommends practicing the right-hand part of the first twenty bars (the A section) in three distinct modes of articulation and dynamics simultaneously, the top voice forte and legato, the middle one mp, and the lowest semiquavers in pp and staccato. Concerning the legato Cortot states that the intensity of tone is imparted "by pressure and not by attack." He further observes that legato of notes played in succession by the same finger can only be achieved by the portamento device."[20] His exercises for the double notes of the middle section stress "firm position of the hand" and "vigour of attack." In regard to the pedal Cortot recommends pedal changes synchronized with the bass line (six changes per bar), although many critics say this is too much to be necessary. No pedal indication by Chopin is found in manuscripts or original editions.[21]

Paraphrases and arrangements

Leopold Godowsky’s version for the left hand alone in his Studies on Chopin's Études is a "rather faithful transformation" "creating the illusion of two-hand writing."[22] It is transposed to D flat major.

Transcriptions for voice with a relative adaptation of words already existed in Chopin’s time. When he was in London in 1837, he heard Maria Malibran sing one of these "adaptations" and pronounced himself extremely pleased.[23][24]

The Étude, or at least its last section, was orchestrated in 1943 or 1944 in Birkenau by Alma Rosé for a highly peculiar lineup of Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz to be performed in secret for the band's members and trusted inmates, as music by Polish composers was strictly forbidden.

In popular culture

The memorable simplicity of the theme has led to its widespread use across a variety of media. In popular usage, it is invariably performed at a slower tempo marking than the original.

Film and television

- Performed at the beginning of Columbo: Suitable for Framing (1971) when art Critic Dale Kingston (Ross Martin) kill his uncle.

- Performed in the film Jezebel (1938).

- Featured in the film I Walked with a Zombie (1943).

- As the song "Tristesse", prominently featured in the 1945 film A Song to Remember which was based on Chopin's life.

- The 1957 silent film comedy compilation The Golden Age of Comedy features the piece as its main theme, arranged for banjo.

- Featured in "Autumn in My Heart", the first instalment of the Korean drama series Endless Love

- The piece was played as a violin variation by Kahoko in the manga series La Corda D'Oro.

- The theme song to Gankutsuou, "We Were Lovers" by Jean-Jacques Burnel, is based upon this melody.

- The piece was played in the TV series Dark Angel (ep: "The Berrisford Agenda") by Alec.[25]

- This piece is also featured in the series finale of the 2003 anime adaptation of Fullmetal Alchemist.

- In the 2005 film The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, the scene where Perkins (Tommy Lee Jones) is drinking in a rural Mexican Cantina features a young girl playing the work on an out-of-tune piano in the background.

- In the series Ultraman Max, a variation of this piece is present in episode 15. A blind orphan plays the tune on her piccolo to calm the raging Kaiju named IF. The kaiju and the girl then play the tune together, with IF growing multiple musical instruments to replicate the melody.

- Featured in the closing of the short film "Baby Blue" from the anthology Genius Party (2007)

- In the 2007 Taiwanese idol drama Bull Fighting, this piece is first featured in episode 8 where Shen Ruo He (played by Mike He) and Yi Sheng Xue (played by Hebe Tien) went on a date in a posh restaurant and is subsequently played in key scenes where the lovers were forced to part.

- The piece was played at the beginning of episode 5, season 3 of The Walking Dead.

- The piece is also heard in the Futurama series finale, "Meanwhile".

- Featured in the film Medianeras (2011).

- Featured in the film Testament of Youth (film) (2014), being played on the piano by Edward Brittain (Taron Egerton).

Music

- The 1938 song "Memories of Chopin" by Viennese Singing Sisters, a vocal arrangement with German words

- The 1939 song "Tristesse" by Tino Rossi

- The tango "La melodía del corazón" recorded by the orchestra of Edgardo Donato with singer Romeo Gavio in 1940, and later the orchestra of Francisco Canaro with singer Francisco Amor, also 1940.

- The song "Never Again", with lyrics by Hal Moore and recorded by the LeRoy Holmes Orchestra and Chorus, uses this melody.

- The 1950 popular song "No Other Love", a hit for Jo Stafford, is derived from this melody.

- James Last included an orchestral version on his album In Concert (1971).

- Richard Clayderman has two instrumental versions: the downbeat "Tristesse" (from "La musique de l'amour", 1980); and the more upbeat, samba-styled "Bye bye tristesse" (from "Medley Concerto", 1979).

- The song "So Deep Is The Night", which was a UK hit for comedian and singer Ken Dodd in 1964, also used the same melody.

- The 1998 studio album Romantic Moments by André Rieu featured Etude Op.10, No.3

- The song "Divina Ilusión" by José José is an adaptation of this melody. It was released in the 1975 album "Tan Cerca...Tan Lejos".

- Serge Gainsbourg's "Lemon Incest" in Love on the Beat (1984).

- The song "Dans la Nuit" by Sarah Brightman is derived from this melody. It was first released in the album Classics in 2001.

- Michiru Oshima's Wakare no Kyoku (別れの曲 lit. music for parting) composition was inspired by the first movement of this melody.

- The song "Heart Breaking Day" (離人節) by Jolin Tsai uses this melody in the intro and instrumental part of the song.

- The 2008 song "Libie Qu" (離別曲, Farewell Song) by Sandee Chan.

- The song "This Day of Days" by Jerry Vale uses this melody.

- The song with the original Polish lyrics was recorded by Manca Izmajlova and the Russian State Symphony Cinema Orchestra in 2007 for her album Slavic Soul, with a new arrangement by Slavko Avsenik Jr.

- The melody is featured in Survival by Muse, which was the official theme for the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.

- The introduction is featured in the song "Wind" by South Korean singer Cho Kyuhyun in his 2nd minialbum Fall, Once Again.

Notes and references

- ↑ ("French edition"). Paris: M. Schlesinger, June 1833.

- ↑ ("German edition"). Leipzig: Fr. Kistner, August 1833 .

- ↑ ("English edition"). London: Wessel & Co, August 1833.

- ↑ Niecks, Frederick (1890). FREDERICK CHOPIN AS A MAN AND MUSICIAN (Vol. II ed.). London & New York: Novello, Ewer & Co. p. 253. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ Niecks, Frederick. Chopin as a Man and Musician. 2 vols. London: Novello, Ewer and Co., 1888. 3rd ed., 1902, vol.2, p.268.

- ↑ Huneker, James. "The Studies—Titanic Experiments." In Chopin: The Man and His Music. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1900.

- ↑ Leichtentritt, Hugo. "Die Etüden." In Analyse der Chopin’schen Klavierwerke [Analysis of Chopin’s Piano Works]. Band II. Berlin: Max Hesses Verlag, 1922, p. 95.

- ↑ See also: Temperley, Nicholas. "Chopin, Fryderik Franciszek. § 8: Pianistic style." In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 6th ed., 20 vols., edited by Stanley Sadie. Vol. 4. London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1980, p. 302.

- ↑ Casella, Alfredo. F. Chopin. Studi per pianoforte. Milano: Edizioni Curci, 1946, p. 21.

- ↑ Leichtentritt, p. 96.

- ↑ Leichtentritt, p. 99

- ↑ Ekier, Jan, ed. (National Edition). "Source Commentary." Chopin Etudes. Warsaw: Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1999, p. 146.

- ↑ Leichtentritt, p. 95.

- ↑ Huneker (1900)

- ↑ Ekier, Jan, ed. (National Edition). "Performance Commentary." Chopin Etudes. Warsaw: Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1999, p. 138.

- ↑ ("French edition"). Paris: M. Schlesinger, June 1833.

- ↑ Lear, Angela Chopin’s Grande Etudes. 5 February 2007.

- ↑ Schumann, Robert. "Die Pianoforte-Etuden, ihren Zwecken nach geordnet" ["The Pianoforte Études, Categorized According to their Purposes"]. Neue Zeitschrift für Musik No.11, 6 February 1836, p.46.

- ↑ Cortot, Alfred. Frédéric Chopin. 12 Études, op.10. Édition de travail des oeuvres de Chopin. Paris: Éditions Salabert, 1915, p. 20

- ↑ Cortot, p. 20

- ↑ "French," "German" and "English" editions

- ↑ Hamelin, Marc-André. "Godowsky’s Studies on Chopin’s Etudes." Liner notes for Godowsky: The Complete Studies on Chopin’s Etudes. Hyperion. CDA67411/2, 2000, p. 15.

- ↑ Casella, p. 21.

- ↑ Willis, Peter (2009). "Chopin in Britain: Chopin's visits to England and Scotland in 1837 and 1848". Durham University. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0204993/faq?ref_=tt_faq_1#.2.1.1

External links

- Analysis of Chopin Etudes at Chopin: the poet of the piano

- Études Op.10: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Manca Izmajlova – F. Chopin – Etude n.3 Tristesse (Live 2010) sung by Manca Izmajlova with the Russian State Symphony Cinema Orchestra (YouTube)

- Étude Op. 10, No. 3 played by Ignacy Jan Paderewski (YouTube)

- Étude Op. 10, No. 3 played by Alfred Cortot (YouTube)

- Étude Op. 10, No. 3 played by Vladimir Horowitz (YouTube)

- Etude in E, Opus 10, No. 3 played by Valentina Igoshina (YouTube)

- Chopin/Godowsky Op.10 No.3 (left hand) played by Marc-André Hamelin (YouTube)