Žiče Charterhouse

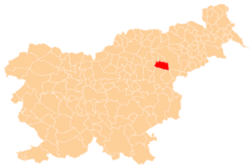

The Žiče Charterhouse (Latin: Domus in Valle Sancti Johannis)[1] was a Carthusian monastery or charterhouse in the narrow valley of Žičnica Creek, also known as Saint John the Baptist Valley (Slovene: dolina svetega Janeza Krstnika) after the church dedicated to John the Baptist at the monastery near the village of Žiče (German: Seiz, formerly Seitz)[2] in the Municipality of Slovenske Konjice in northeastern Slovenia.

The charterhouse was founded between 1155 and 1165, and was the first Carthusian monastery in the German sphere of influence of the time, and also the first outside France or Italy. The monastery also had one of the first pharmacies in what is now Slovenia.[3]

The monastery was abolished in 1782, but the buildings survive or are being recreated.

History

The Žiče Charterhouse was founded between 1155 and 1165 by Ottokar III of Styria, the Margrave of Styria,[4] and his son Duke Ottokar IV of Styria, of the house of Traungau, both of whom were buried there.[5] The monastery was settled by Carthusian monks from the Grande Chartreuse in France (Ecclesia Maior), which also financed the construction, led by Master Aynard, and influenced the arrangement of the premises. As with French charterhouses, two monasteries were built here: the upper one (the Žiče Charterhouse), where the cloister monks lived according to the strict rule of the Carthusians; and the lower one in the village of Špitalič for the lay monks, who spent less time in prayer and worked as craftsmen, supporting the upper monastery and contributing to its prosperity. The monastery church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist was consecrated on 24 October 1190 by Patriarch Berthold of Aquileia.

At the time of the Great Schism in the western Roman Catholic church in the 14th century, the Žiče Charterhouse became the seat of the Prior General of the Carthusian order for a while in 1391.

The monastery was attacked during an Ottoman raid in 1531. This marked the beginning of a decline in its influence and fortunes. In 1564 it passed into the hands of commendatory abbots and in 1591 to the Jesuits of Graz. It was recovered by the Carthusians in 1593, after which it prospered again. In 1782 Emperor Joseph II abolished the monastery, one of the earliest to be dissolved under the Josephine Reforms.

The charterhouse was allowed to fall into decay. The ruins were bought from the religious foundation in 1826 by Prince Weriand of Windisch-Graetz and remained the property of this family until the end of World War II. Now the owner is the Municipality of Slovenske Konjice.

Pseudoetymology

The following legend is a pseudoetymology of the monastery name. When the Margrave of Styria Ottokar III returned from the Second Crusade, he wished for some relaxation and therefore visited Leopold from Gonobitz to go hunting on Mount Konjice (Slovene: Konjiška gora). Coincidentally he came to a shady hollow in the south part of the mountain, where suddenly an extremely white hind appeared in front of him. He followed it as bewitched on his horse, but because he was not able to catch it he fell asleep in the shade on the hot summer afternoon (on St. John the Baptist's day). A man in a white fur coat appeared in his dream and revealed himself as St. John the Baptist, ordering him to build a monastery on this place. At that moment a rabbit jumped into Ottokar's lap because it was frightened by the hunter's screaming. The saint's image disappeared and Ottokar shouted: "A rabbit, look, a rabbit!" Because of this rabbit the monastery was called "Seiz Charterhouse" (the Slovenian pronunciation of rabbit, zajec, is written Seiz in German) for a long time and has the initial "S" in its coat of arms.

Library

Soon the monastery became a center of culture and politics in its territory and far beyond. The Carthusian Prior General from Žiče, Stephen Maconi, a friend of Saint Catherine of Siena connected the politically and ecclesiastically divided continent of Europe from this place. In the 14th century the monastery had a library of over 2,000 volumes (mostly manuscripts) which was larger than all but the Vatican library.

On 30 May 1487, the visiting Bishop of Caorle stayed at the Žiče charterhouse as an emissary of the Patriarch of Aquileia. His secretary Paolo Santonino wrote in his Itinerary[6] that the monks had more than 2,000 volumes (manuscripts). Now only 120 are known, with fragments of a further 100 or so.

In the mid-16th century, as the result of a number of tragic events in the preceding half-century, the monastery was nearly abandoned and Archduke Charles II of Styria ordered the books to be moved to the library of the Jesuit College in Graz.

Žiče manuscripts

The Carthusian order never preached religion through the spoken word, but took to spreading it in writing, accepting into the order only people with a good knowledge of foreign languages (mostly German, Latin, and Greek) and exemplary writing skills. They devoted a large part of their lives to producing precise copies of existing texts as well as creating new ones on a wide range of topics, from theology to astronomy, from practical sciences to those more literary in nature. Among the texts still in existence are many notable works which are part of the intellectual heritage of this region and the wider Middle-European sphere.

Despite the loss of most of the manuscripts, the remnants of impressive library can still provide a valuable insight into several centuries of continuous development of the medieval book. Today about 120 manuscripts and 100 fragments are known. This is only a fraction of the whole, and even this small part is almost entirely outside Slovenian borders. Yet this is the only group of medieval manuscripts from Slovenia, making it possible to follow nearly four centuries of unbroken manuscript production within one monastic community. The manuscripts from the Žiče Charterhouse include many notable texts written by authors living in Žiče or the nearby Jurklošter Charterhouse. Examples include texts by Phillip of Žiče (Seitz), Nicolaus Kempf, and Sifried of Swabia.

Several of these manuscripts are also signed by monks or copyists from outside, who were probably benefactors, and their hand-written works makes of rich palette of paleographical forms. It is also the only group of manuscripts in Slovenia which is complete enough to follow the development of flourished (penwork) initials and consequently to speak about the "Žiče style". Some manuscripts also display colourful painted initials and other illuminated elements, created by professional and—as was common practice in those times—by itinerant painters.

Present day

Today the charterhouse is an important cultural monument with about 20,000 visitors per year. Reconstruction work under expert supervision is still in progress. Just outside the charterhouse is the Gastuž Inn, purporting to be the oldest inn on Slovenian territory (dating to 1467).

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Žiče Charterhouse. |

- ↑ Schlegel, Gerhard; Hogg, James (2004). Monasticon Cartusiense (in German). Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik. p. 43. ISBN 9783900033033.

- ↑ The name appears in various forms in early written documents: Seitz (1185), Sitze (1186, 1243), Seiz (1202, 1234), Sishe (1229), Seitis (1233), Sits (1235, 1257), Siz (1237), Syces (1240), Sic (1243), Syces (1245), Siths (1247), Seits (1257)

- ↑ Zdovc, Vinko Žička kartuzija, Kratka zgodovina bogate preteklosti Kartuzije 1165-1782. Slovenske Konjice 1997

- ↑ As with most medieval monasteries there is a foundation legend, which in this case relates that Ottakar was led to the site when he became lost in dense forest during a hunt.

- ↑ The bodies were later moved to Rein Abbey

- ↑ Itinerario in Carinzia, Stiria e Carniola (1485-1487), transl. Roberto Gagliardi, published 1999, Biblioteca de L'unicorno. ISBN 88-8147-202-3

Coordinates: 46°18′39.96″N 15°23′33.39″E / 46.3111000°N 15.3926083°E