United States occupation of the Dominican Republic (1916–24)

| United States occupation of the Dominican Republic (1916–24) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Banana Wars | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 1,800 marines | Arias's militiamen: 1,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 7 killed, 15 wounded | 100-300 killed or wounded | ||||||||

The first United States occupation of the Dominican Republic lasted from 1916 to 1924. It was one of the many interventions in Latin America undertaken by the military forces of the United States in the 20th century. On May 13, 1916,[1] Rear Admiral William B. Caperton forced the Dominican Republic's Secretary of War Desiderio Arias, who had seized power from Juan Isidro Jimenes Pereyra, to leave Santo Domingo by threatening the city with naval bombardment.[1]

Invasion

The piecemeal invasion resulted in the US Navy occupying all key positions in government and controlling the army and police. The first landing took place on May 5, 1916, when "two companies of marines landed from the USS Prairie at Santo Domingo."[2] Their goal was to offer protection to the U.S. Legation and the U.S. Consulate, and to occupy the Fort San Geronimo. Within hours, these companies were reinforced with "seven additional companies."[3] On May 6, forces from the U.S.S. Castine landed to offer protection to the Haitian Legation, a country under similar military occupation from the U.S. Two days after the first landing, constitutional President, Juan Isidro Jimenes resigned.[4]

Admiral Caperton's forces occupied Santo Domingo on May 15, 1916. Colonel Joseph H. Pendleton's marine units took the key port cities of Puerto Plata and Monte Cristi on June 1, and enforced a blockade.[5] Two days after the Battle of Guayacanas, on July 3, marine forces moved to Arias' stronghold in Santiago de los Caballeros.[6] However, "A military encounter was avoided when Arias arrived at an agreement with Capteron to cease resistance."[7] Three days after Arias left the country,[1] the rest of the occupation forces landed and took control of the country within two months,[1] and in November the United States imposed a military government under Rear Admiral Harry Shepard Knapp.[1]

The beginning of the Occupation

.jpg)

Marines claimed to have restored order throughout most of the republic, with the exception of the eastern region, but resistance continued widespread in both, direct and indirect forms in every place.[8] The US occupation administration, however, measured its success through these standards: the country's budget was balanced, its debt was diminished, economic growth directed now toward the US; infrastructure projects produced new roads that allowed the movement of military personnel across all the country's regions for the first time in history;[9] a professional military organization that took away the power from local elites and made soldiers more loyal to the national government, the Dominican Constabulary Guard, replaced the former partisan forces responsible for the civil war with groups less hostile to the US occupation.[10]

Most Dominicans, however, greatly resented the loss of their sovereignty to foreigners, few of whom spoke Spanish or displayed much real concern for the welfare of the republic. A guerrilla movement, known as the gavilleros,[1] with leaders such as General Ramon Natera, enjoyed considerable support from the population in the eastern provinces of El Seibo and San Pedro de Macorís.[1] Having knowledge of the local terrain, they fought against the United States occupation from 1917 to 1921.[11] The fighting in the countryside ended in a stalemate, and the guerrillas agreed to a conditional surrender.

Withdrawal

After World War I, public opinion in the United States began to run against the occupation.[1] Warren G. Harding, who succeeded Wilson in March 1921, had campaigned against the occupations of both Haiti and the Dominican Republic.[1] In June 1921, United States representatives presented a withdrawal proposal, known as the Harding Plan, which called for Dominican ratification of all acts of the military government, approval of a loan of US$2.5 million for public works and other expenses, the acceptance of United States officers for the constabulary—now known as the National Guard (Guardia Nacional)—and the holding of elections under United States supervision. Popular reaction to the plan was overwhelmingly negative.[1] Moderate Dominican leaders, however, used the plan as the basis for further negotiations that resulted in an agreement between U.S. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes and Dominican Ambassador to the United States Francisco J. Peynado on June 30, 1922,[12] allowing for the selection of a provisional president to rule until elections could be organized.[1] Under the supervision of High Commissioner Sumner Welles, Juan Bautista Vicini Burgos assumed the provisional presidency on October 21, 1922.[1] In the presidential election of March 15, 1924, Horacio Vásquez Lajara, an American ally who cooperated with the United States government, handily defeated Peynado. Vásquez's Alliance Party (Partido Alianza) also won a comfortable majority in both houses of Congress.[1] With his inauguration on July 13, control of the republic returned to Dominican hands.[1]

Aftermath

Despite the withdrawal, there were still concerns regarding the collection and application of the country's custom revenues. To address this problem, representatives of the United States and the Dominican Republic governments met at a convention and signed a treaty, on December 27, 1924, which gave the United States control over the country's custom revenues.[13] In 1941, the treaty was officially repealed and control over the country's custom revenues was again returned to the government of the Dominican Republic.[13] However this treaty created lasting resentment of the United States among the people of the Dominican Republic.[14]

The Dominican Campaign Medal was an authorized U.S. service medal for those military members who had participated in the conflict.

Gallery

-

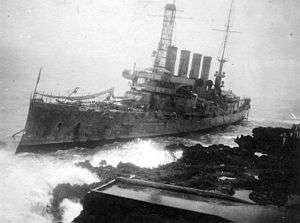

USS Memphis wrecked at Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, where she was thrown ashore by rogue waves on the afternoon of August 29, 1916.

See also

- Banana Wars

- History of the Dominican Republic

- Battle of Guayacanas

- Battle of San Francisco de Macoris

- United States occupation of the Dominican Republic (1965–66)

External links

- About.Com: The US Occupation of the Dominican Republic, 1916-1924

- globalsecurity.org:Dominican Republic Occupation (1916-24)

- Country Studies: Occupation by the United States, 1916-24

- The American War Library: Numbers of Americans Killed/Wounded, by Action

Links in Spanish

- Educando: Causas y consecuencias de la invasión norteamericana de 1965 en la República Dominicana

- Hoy: La intervención militar norteamericana de 1965

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "USA Dominican Republic Resistance 1917-1921". The Dupuy Institute. December 16, 2000. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ↑ United States Naval Institute (1879). Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. Annapolis, Md: U.S. Naval Institute. p. 239.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Atkins, G. Pope & Larman Curtis Wilson. (1998). The Dominican Republic and the United States: From Imperialism to Transnationalism. Athens, Ga.: Univ. of Georgia Press. p. 49. ISBN 0820319309.

- ↑ Musicant, Ivan (1990). The Banana Wars. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co. pp. 247–252. ISBN 0025882104.

- ↑ Musicant. Banana Wars. pp. 253–263.

- ↑ Atkins and Wilson (1998). The Dominican Republic and the United States. p. 49.

- ↑ Franks, Julie (June 1995). "The Gavilleros of the East: Social Banditry as Political Practice in the Dominican Sugar Region 1900-1924". Journal of Historical Sociology. 8 (2): 158–181.

- ↑ Emmer, P. C., Bridget Brereton, B. W. Higman (2004). "Education in the Caribbean," a chapter in General History of the Caribbean: The Caribbean in the Twentieth Century. Paris, London: UNESCO. p. 609. ISBN 0-333-724593.

- ↑ Haggerty, Richard A. (1989). "OCCUPATION BY THE UNITED STATES, 1916-24". Dominican Republic: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ↑ McPherson, Alan (2013). Encyclopedia of U.S. Military Interventions in Latin America. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 223–2. ISBN 1598842609.

- ↑ Calder, Bruce J. (1984). The Impact of Intervention: The Dominican Republic during the U.S. Occupation of 1916–1924. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 223. ISBN 978-1-55876-386-9. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- 1 2 JSTOR 2213777

- ↑ American foreign relations: a history. Since 1895, Volume 2, pg. 163