United States occupation of Veracruz

- For other battles at Veracruz see Battle of Veracruz (disambiguation).

| United States occupation of Veracruz | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Banana Wars, Mexican Revolution, and the Border War | |||||||

Sergeant Major John H. Quick of the U.S. Marines raises the American flag over Veracruz. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,300 | ≈500 regular military personnel, unknown number of militiamen | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

22 killed 70 wounded |

152–172 soldiers killed[1] 195–250 wounded 150+ militia killed[2] Unknown number of civilians killed[3][4] | ||||||

The United States occupation of Veracruz began with the Battle of Veracruz and lasted for seven months, as a response to the Tampico Affair of April 9, 1914. The incident came in the midst of poor diplomatic relations between Mexico and the United States, and was related to the ongoing Mexican Revolution.

Background

The Tampico Affair was set off when nine American sailors were arrested by the Mexican government for entering off-limit areas in Tampico, Tamaulipas.[5] The unarmed sailors were arrested when they entered a fuel loading station. The sailors were released, but the U.S. naval commander demanded an apology and a twenty-one gun salute. The apology was provided but not the salute. In the end, the response from U.S. President Woodrow Wilson ordered the U.S. Navy to prepare for the occupation of the port of Veracruz. While awaiting authorization from the U.S. Congress to carry out such action, Wilson was alerted to a delivery of weapons for Victoriano Huerta, who had taken control of Mexico the previous year after a bloody coup d'état (and would eventually be deposed on July 15, 1914), due to arrive in the port on April 21 aboard the German-registered cargo-steamer SS Ypiranga. As a result, Wilson issued an immediate order to seize the port's customs office and confiscate the weaponry. The weapons had actually been sourced by John Wesley De Kay, an American financier and businessman with large investments in Mexico, and a Russian arms dealer from Puebla, Leon Rasst, not the German government as newspapers reported at the time.[6] Huerta had usurped the presidency of Mexico with the assistance of the American ambassador Henry Lane Wilson during a coup d'état in February 1913 known as La decena trágica. The Wilson administration's answer to this was to declare Huerta a usurper of the legitimate government, to embargo arms shipments to Huerta, and to support the Constitutional Army of Venustiano Carranza.

The arms shipment to Mexico, in fact, in part originated from the Remington Arms company in the U.S., went to Odessa, Russia to Hamburg, where De Kay added to the load. The arms and ammunition were to be shipped via Hamburg, Germany, to Mexico allowing Huerta's arms dealers to skirt the American arms embargo.[6] The landing of the arms was blocked at Veracruz but they were discharged a few weeks later in Puerto Mexico, a port controlled by Huerta at the time.

Initial landing

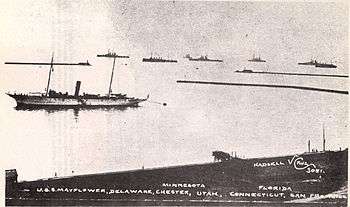

On the morning of April 21, 1914, warships of the United States Atlantic Fleet under the command of Rear Admiral Frank Friday Fletcher, began preparations for the seizure of the Veracruz waterfront.

At 11:12 hrs, consul William Canada watched from the roof of the American Consulate that the first boatload of Marines were leaving the auxiliary vessel USS Prairie.[7][8]

By 11:30, with whaleboats swung over the side, 502 U.S. Marines from the 2nd Advanced Base Regiment, 285 armed Navy sailors, known as "Bluejackets," from the battleship USS Florida and a provisional battalion composed of the Marine detachments from Florida and her sister ship USS Utah also began landing operations.

As the landing party moved toward pier 4, Veracruz's main wharf, a large crowd of Mexican and American citizens gathered to watch the spectacle. The invaders encountered no resistance as they exited the whaleboats, formed ranks into a Marine and a seaman regiment, and began marching toward their objectives. This initial show of force was enough to prompt the retreat of the Mexican forces led by General Gustavo Maass. In the face of this, Commodore Manuel Azueta encouraged cadets of the Veracruz Naval Academy to take up the defense of the port for themselves. Also, about 200 line soldiers of the Mexican Army remained behind to fight the invaders along with the citizens of Veracruz.

Battle of Veracruz

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Mexico |

|

|

Spanish rule |

| Timeline |

|

|

.jpg)

Three Navy rifle companies were instructed to capture the customs house, post and telegraph offices, while the Marines went for the railroad terminal, roundhouse and yard, the cable office and the power-plant.[9]

Arms were distributed to the population, who were largely untrained in the use of Mausers and had trouble finding the correct ammunition. In short, the defense of the city by its populace was hindered by the lack of central organization and a lack of adequate supplies. The defense of the city also included the release of the prisoners held at the "La Galera" military prison, not those at San Juan de Ulúa (some of whom were political prisoners) who were later attended to by the U.S. Navy.[10]

Although the landing had been nearly unopposed as U.S. forces marched into the city, Veracruz quickly became a battleground. Just after noon, fighting began with the 2nd Advance Base Regiment under Colonel Wendell C. Neville becoming heavily involved in a firefight in the rail yards. While the forces ashore slowly fought their way forward, Admiral Fletcher landed Utah's 384 man bluejacket battalion, the only other unit at his disposal. By mid afternoon, the Americans had occupied all of their objectives and Admiral Fletcher called a general halt to the advance, initially hoping that a cease-fire could be arranged. That hope rapidly faded as he could find no one to bargain with and all troops in the city were instructed to remain on the defensive pending the arrival of reinforcements.

On the night of April 21, Fletcher decided that he had no choice but to expand the initial operation to include the entire city, not just the waterfront.[11] Five additional U.S. battleships and two cruisers had reached Veracruz during the hours of darkness and they carried with them Major Smedley Butler and his Marine Battalion which had been rushed from Panama. The battleship's seaman battalions were quickly organized into a regiment 1,200 men strong, supported by the ship's Marine detachments providing an additional 300-man battalion. These newly arrived forces went ashore around midnight to await the morning's advance.

At 07:45 April 22, the advance began. The Leathernecks adapted to street fighting, which was a novelty to them. The sailors were less adroit at this style of fighting. A regiment led by Navy Captain E. A. Anderson advanced on the Naval Academy in parade ground formation, making his men easy targets for the partisans barricaded inside (the cadets had left Veracruz the night before, after suffering a few casualties [12]). This attack was initially repulsed; soon, the attack was renewed, with artillery support from three warships in the harbor, Prairie, San Francisco, and Chester, that pounded the Academy with their long guns for a few minutes, silencing all resistance.

That afternoon, the First Advanced Base Regiment, originally bound for Tampico, Tamaulipas, came ashore under the command of Colonel John A. Lejeune and by 17:00, U.S. troops had secured the town square and were in complete control of Veracruz. Some pockets of resistance continued to occur around the port, mostly in the form of hit-and-run guerrilla tactics, but by April 24 all fighting had ceased.

A third provisional regiment of Marines, assembled at Philadelphia, arrived on May 1 under the command of Colonel Littleton W. T. Waller, who assumed overall command of the Brigade, by that time numbering some 3,141 officers and men. By then, the sailors and Marines of the Fleet had returned to their ships and an Army Brigade had landed. Marines and soldiers continued to garrison the city until the U.S. withdrawal on November 23, which occurred after Argentina, Brazil and Chile (the three ABC Powers, the most powerful and wealthy countries in South America) were able to settle the issues between the two nations at the Niagara Falls peace conference.[13]

Aftermath

U.S. Army Brigadier General Frederick Funston was placed in control of the administration of the port. Assigned to his staff as an intelligence officer was a young Captain Douglas MacArthur.[14] While Huerta and Carranza officially objected to the occupation, neither was able to oppose it effectively, being more preoccupied by events of the Mexican Revolution. Huerta was eventually overthrown and Carranza's faction took power. The occupation, however, brought the two countries to the brink of war and worsened U.S.-Mexican relations for many years. The ABC Powers held the Niagara Falls peace conference in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada, on May 20 to avoid an all-out war over this incident. A plan was formed in June for the US troops to withdraw from Veracruz after General Huerta surrendered the reins of his government to a new regime and Mexico assured the United States that it would receive no indemnity for its losses in the recent chaotic events.[15] Huerta soon afterwards left office and gave his government to Carranza. Carranza, who was still quite unhappy with US troops occupying Veracruz,[15] rejected the rest of the agreement.[15] In November 1914, after the Convention of Aguascalientes ended and Carranza failed to resolve his differences with revolutionary generals Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, Carranza left office for a short period and handed control to Eulalio Gutiérrez Ortiz.

During this brief absence from power, however, Carranza still controlled Veracruz and Tamaulipas. After leaving Mexico City, Carranza fled to the state of Veracruz,[16] made the city of Cordoba the capital of his regime and agreed to accept the rest of the terms of Niagara Falls peace plan. The US troops officially departed on November 23.[15] Despite their previous spat, diplomatic ties between the US and the Carranza regime greatly extended, following the departure of US troops from Veracruz,.[15]

After the fighting ended, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels ordered that fifty-six Medals of Honor be awarded to participants in this action, the most for any single action before or since. This amount was half as many as had been awarded for the Spanish–American War, and close to half the number that would be awarded during World War I and the Korean War. A critic claimed that the excess medals were awarded by lot.[17][18] Major Smedley Butler, a recipient of one of the nine Medals of Honor awarded to Marines, later tried to return it, being incensed at this "unutterable foul perversion of Our Country's greatest gift" and claiming he had done nothing heroic. The Department of the Navy told him to not only keep it, but wear it.

Lt. Azueta and a Naval Military School cadet, Cadet Midshipman Virgilio Uribe, who also died during the fighting, are now part of the roll call of honor read by all branches of the Mexican Armed Forces in all military occasions, alongside the six Niños Héroes of the Military College (nowadays the Heroic Military Academy) who died in defense of the nation during the Battle of Chapultepec on September 13, 1847. As a result of the brave defense put up by the Naval School cadets and faculty, it has now become the Heroic Naval Military School of Mexico in their honor by virtue of a congressional resolution in 1949.

Political consequences

As an immediate reaction to the military invasion of Veracruz several anti-American revolts broke out in Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, and Uruguay.[19] US citizens were expelled from Mexican territory and they had to be accommodated in refugee campuses at New Orleans, Texas City, and San Diego.[20] Even the British government was privately irritated, because they had previously agreed with Woodrow Wilson that the United States would not invade Mexico without a previous warning.[19] The military invasion of Veracruz was also a decisive factor in favor of keeping Mexico neutral in World War I.[21] Mexico refused to participate with the United States in its military excursion in Europe and granted full-guarantees to the German companies for keeping their operations open, especially in Mexico City.[22]

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson considered another military invasion of Veracruz and Tampico in 1917-1918,[23][24] so as to take control of Tehuantepec Isthmus and Tampico oil fields,[24][25] but this time the new Mexican President Venustiano Carranza gave the order to destroy the oil fields in case the Marines tried to land there.[26][27] As a scholar once wrote: "Carranza may not have fulfilled the social goals of the revolution, but he kept the gringos out of Mexico City".[28][29]

In Mexico, this intervention (1914) "is immortalized in Mexico's national memory as one of the ugliest deeds ever inflicted upon the country by its neighbor to the north",[30] though not as much as "robbing" Mexico of more than half of its territory: Texas (1834) and some years later California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico and Arizona (1848).[31]

In popular culture

- Warren Zevon's album Excitable Boy features a track called "Veracruz" named after this event. It depicts the battle and chaos for what one may presume was the point of view of a resident of Veracruz. The last verse, written in Spanish, is the character saying he will return to Veracruz, destiny has changed his life and in Veracruz he shall die.

- 1914 Veracruz is also the setting for The Hot Country, a 2012 novel by Robert Olen Butler.

Bibliography

- Botte, M. Louis. Magazine L'Illustration, artícle "Les Américains au Mexique", 13 Juin 1914. (See Wikisource)

- Eisenhower, John S.D. (1995), "Intervention! The United States and the Mexican Revolution, 1913-1917", New York: W.W. Norton & Company

- O'Shaughnessy, Edith, (1916), "A Diplomat's Wife in Mexico", Harper & Brothers Publichers

- Quirk, Robert E. (1967). An Affair of Honor: Woodrow Wilson and the Occupation of Veracruz, W. W. Norton & Company.

- Sweetman, Jack (1968). The Landing at Veracruz: 1914. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States occupation of Veracruz. |

- Victoriano Huerta

- Mexican Revolution

- Tampico Affair

- Theodore C. Lyster, U.S. Army's Chief Health Officer in the conflict

- United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution

Footnotes

- ↑ Alejandro de Quesada, "The Hunt for Pancho Villa: The Columbus Raid and Pershing’s Punitive Expedition", page 12. Osprey Publishing, March 2012.

- ↑ Gastón García Cantú (1996) Las invasiones norteamericanas en México, p. 276, Fondo de Cultura Económica, México.

- ↑ Alan McPherson (2013) Encyclopedia of U.S. Military Interventions in Latin America, p. 393, ABC-CLIO, USA.

- ↑ Susan Vollmer (2007) Legends, Leaders, Legacies, p. 79, Biography & Autobiography, USA.

- ↑ "The Border - 1914 The Tampico Affair and the Speech from Woodrow Wilson". PBS. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- 1 2 Heribert von Feilitzsch, Felix A. Sommerfeld: Spymaster in Mexico, 1908 to 1914, Henselstone Verlag, Amissville, VA 2012, pp. 351ff

- ↑ The Landing at Veracruz: 1914, by Jack Sweetman, 1968, ch. 6, p. 58

- ↑ "Logbook of HMS Essex". naval-history.net. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ Jack Sweetman, “The Landing at Veracruz: 1914” 1968, p67

- ↑ A Diplomat's Wife in Mexico, by Edith O'Shaughnessy, 1916, Ch. XXIV

- ↑ Boot, Max (2003). The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. New York: Basic Books. p. 152. ISBN 046500721X. LCCN 2004695066.

- ↑ "Parte de Novedades" of commodore Manuel Azueta (in Spanish)

- ↑ Kennedy Hickman. "Mexican Revolution Battle of Veracruz". About. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ William Manchester. American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880–1964, Little, Brown and Company, 1978, pp. 73–76

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The ABC Conference (May-June 1914)". u-s-history.com. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ Kennedy Hickman. "Pancho Villa: Mexican Revolutionary". About. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ Gallery, p. 118

- ↑ Medal of Honor Recipients Veracruz 1914

- 1 2 Michael Small (2009) The Forgotten Peace: Mediation at Niagara Falls, 1914, p. 35, University of Ottawa, Canada.

- ↑ John Whiteclay Chambers & Fred Anderson (1999) The Oxford Companion to American Military History, p. 432, Oxford University Press, England.

- ↑ Lee Stacy (2002) Mexico and the United States, Volume 3, p. 869, Marshall Cavendish, USA.

- ↑ Jürgen Buchenau (2004) Tools of Progress: A German Merchant Family in Mexico City, 1865-present, p. 82, UNM Press, USA.

- ↑ Ernest Gruening (1968) Mexico and Its Heritage, p. 596, Greenwood Press, USA.

- 1 2 Drew Philip Halevy (2000) Threats of Intervention: U. S.-Mexican Relations, 1917-1923, p. 41, iUniverse, USA.

- ↑ Lorenzo Meyer (1977) Mexico and the United States in the oil controversy, 1917-1942, p. 45, University of Texas Press, USA

- ↑ Stephen Haber, Noel Maurer, Armando Razo (2003) The Politics of Property Rights: Political Instability, Credible Commitments, and Economic Growth in Mexico, 1876-1929, p. 201, Cambridge University Press, UK.

- ↑ Lorenzo Meyer (1977) Mexico and the United States in the oil controversy, 1917-1942, p. 44, University of Texas Press, USA.

- ↑ Lester D. Langley (2001) The Banana Wars: United States Intervention in the Caribbean, 1898-1934, p. 108, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, USA.

- ↑ Thomas Paterson, John Garry Clifford, Kenneth J. Hagan (1999) American Foreign Relations: A History since 1895, p. 51, Houghton Mifflin College Division, USA.

- ↑ Douglas W. Richmond, "Victoriano Huerta" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 1, p. 658. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- ↑ The Mexican-American War: Two Neighbors go to War for California

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Mitchell Yockelson (1997). "The United States Armed Forces and the Mexican Punitive Expedition: Part 1". Prologue Magazine. 29.

- Gallery, Daniel V. (1968) Eight Bells. Paperback Library.

- Sweetman, Jack (1968). The Landing at Veracruz: 1914. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

- Veterans Museum & Memorial Center (2003). Veterans Museum & Memorial Center, In Memoriam, United States Interventions in Mexico, 1914–1917. Retrieved December 28, 2005.

- President Wilson's Speech in Response to the Tampico Incident, U.S. Department of State, Papers Relating to Foreign Affairs, 1914, pp. 474–476.

- The Tampico Affair and the Speech from Woodrow Wilson to the American People – from the PBS Special The Border, about life on the Mexico–United States border

- von Feilitzsch, Heribert (2012). Felix A. Sommerfeld: Spymaster in Mexico, 1908 to 1914. Amissville, Virginia: Henselstone Verlag LLC. ISBN 9780985031701.

- Sweetman, Jack (2014). "‘Take Veracruz at Once’", Naval History Volume 28, Number 2

Coordinates: 19°11′24″N 96°09′11″W / 19.1900°N 96.1531°W