1976 Tangshan earthquake

| |

| Date |

July 28, 1976 (China time zone) |

|---|---|

| Magnitude | 7.8Mw |

| Depth | 7.5 |

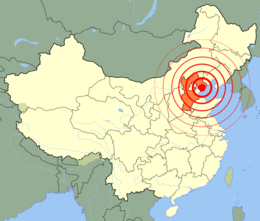

| Epicenter | 39°36′N 118°12′E / 39.60°N 118.20°E (Tangshan, Hebei, China) |

| Areas affected | People's Republic of China |

| Casualties | 242,769–700,000 dead (2nd deadliest earthquake of modern history) |

The Tangshan earthquake, also known as the Great Tangshan earthquake,[1] was a natural disaster that occurred on July 28, 1976. It is believed to be the largest earthquake of the 20th century by death toll.[2] The epicenter of the earthquake was near Tangshan in Hebei, People's Republic of China, an industrial city with approximately one million inhabitants. The number of deaths initially reported by the Chinese government was 655,000, but this number has since been stated to be around 240,000 to 255,000.[2] Another report indicates that the actual death toll was much higher, at approximately 650,000, and explains that the lower estimates are limited to Tangshan and exclude fatalities in the densely populated surrounding areas.[3]

A further 164,000 people were recorded as being severely injured.[4] The earthquake occurred between a series of political events involving the Communist Party of China, ultimately leading to the expulsion of the ruling Gang of Four by Mao Zedong's chosen successor, Hua Guofeng. In traditional Chinese thought, natural disasters are seen as a precursor of dynastic change.[5]

The earthquake hit in the early morning and lasted 14 to 16 seconds.[6] Chinese government official sources state a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter magnitude scale,[4] though some sources listed it as high as 8.2. It was followed by a major 7.1 magnitude aftershock some 16 hours later, increasing the death toll to over 255,000. The earthquake was generated by the 25-mile-long Tangshan Fault, which runs near the city and ruptured due to tectonic forces caused by the Amurian Plate sliding past the Eurasian Plate.

Early warnings and predictions

Well water in a village outside of Tangshan reportedly rose and fell three times the day before the earthquake. Gas began to spout out of a well in another village on July 12 and then increased on July 25 and July 26. City dwellers from the "downtown" area who had fish discovered that the fish were restless, jumping out of the aquarium as if wanting to escape; therefore, some animals may have anticipated the earthquake.[7]

More than half a month before the earthquake struck, Wang Chengmin (汪成民) of the State Seismological Bureau (SSB) Analysis and Prediction Department had already concluded that the Tangshan region would be struck by a significant earthquake between July 22, 1976 and August 5, 1976.[1] Abnormal signals were mentioned for Beijing, Tianjin, Tangshan, Bohai and Zhangjiakou regions. Wang made an effort to publicize the information to 60 people. One of the people listening in Qinglong was official Wang Chunqing (王春青).[1]

The prepared: Qinglong County

After voicing the concerns to Wang Chunqing (王春青), his county took the report very seriously. Already some sources showed that the county had been preparing as much as two years earlier.[8] Up to 800 members of his county tried to respond.[1] On July 25 and 26, 1976 each community of Qinglong county had emergency meetings to prepare and instruct villagers. Buildings were examined and water reservoirs were given special attention. The county secretary in charge, Ran Guangqi (冉广岐) decided to risk his political career and certain jail term to prepare the 470,000 residents of the county for the upcoming earthquake by ordering officials to educate the people as well as evacuate the local population to safer areas.[1]

Damage

The high loss of life caused by the earthquake can be attributed to the time it struck and how suddenly it struck, as well as to the quality and nature of building construction in China. The earthquake lacked the foreshocks that sometimes come with earthquakes of this magnitude. It also struck at just before 4 AM, when most people were asleep and unprepared. Tangshan itself was thought to be in a region with a relatively low risk of earthquakes. Very few buildings had been built to withstand an earthquake, and the city lies on unstable alluvial soil. Therefore, hundreds of thousands of buildings were destroyed.

The earthquake devastated the city over an area of roughly 6.5 kilometres (4.0 mi) by 8 kilometres (5.0 mi). Many of the people who survived the initial earthquake were trapped under collapsed buildings. Tremors were felt as far away as Xi'an approximately 760 km (470 mi) away. Eighty-five percent of the buildings in the city were collapsed into ruins or became uninhabitable.[6] The seismic waves spread far, with damage in cities such as Qinhuangdao and Tianjin, and a few buildings as far away as Beijing, 140 km from the epicenter, were damaged. The economic loss totaled to 10 billion yuan.[4]

Death toll

Controversial statistics

Until fairly recently, China's political environment has made it difficult to properly gauge the extent of natural disasters. Successive governments have placed more importance on the appearance of harmony rather than accurate information on damages. The Tangshan Earthquake came at a rather politically sensitive time during the late stages of the Cultural Revolution, making accurate statistics especially difficult to find. The Tangshan earthquake killed 242,000 people according to official figures, though some sources estimate a death toll up to three times higher. This would make it the deadliest earthquake in modern times, and the second or third deadliest in recorded history. It is worth noting that the population of Tangshan at the time the quake struck was estimated to be around 1.6 million[9] and that most of Tangshan's city proper was flattened.

Many experts believe the Chinese government has never released an accurate death toll for the disaster. The death toll figure of 242,419 came from the Chinese Seismological Service in 1988,[2] while some sources have estimated the death toll to be at 650,000.[10] Others range as high as 700,000.[11] The initial estimates of 655,000 dead and 779,000 injured were released by Hebei Revolutionary Committee.[12]

Aftermath

The Chinese government refused to accept international aid from the United Nations, and insisted on self-reliance.[12] Shanghai sent 56 medical teams to Tangshan, in addition to the People's Liberation Army who were assisting while also trying to fix their tarnished image of Red Guard suppressors.[12] Rebuilding infrastructure started immediately in Tangshan, and the city was completely rebuilt. Today Tangshan city is home to nearly three million people and is known as "Brave City of China."

Political aftermath

The earthquake came in one of the most dramatic years in the history of the People's Republic. The earthquake was preceded by the death of Zhou Enlai in earlier months and followed by the death of Mao Zedong in September. The political repercussions of the disaster and its aftermath contributed to the end of the Cultural Revolution. Mao's chosen successor Hua Guofeng showed concern, thereby solidifying his status as China's leader. He, along with Vice-Premier Chen Yonggui, made a personal visit to Tangshan on August 4 to survey the damage and was photographed in the tasks of cleaning up and comforting the survivors.[13]

Leaders who opposed the return of Deng Xiaoping, especially the group which became known as Gang of Four, filled the press with concern for the victims, but explicitly said that the nation should not be diverted by the earthquake, and that the priority was to denounce Deng instead. Jiang Qing was widely quoted as saying "There were merely several hundred thousand deaths. So what? Denouncing Deng Xiaoping concerns 800 million people."[14] Other Gang of Four slogans said: "Be alert to Deng Xiaoping's criminal attempt to exploit earthquake phobia to suppress revolution!"[15]

Comparison

Within China's geography, the deadliest known earthquake in history occurred in 1556 in Shaanxi, China. The 1556 Shaanxi earthquake is estimated to have killed 830,000 people in China, although reliable figures from this period are hard to verify.[16] Another earthquake is the 1920 Haiyuan earthquake in Gansu Province, which killed an estimated 235,000. In 1927 another earthquake struck in the same area, this time at Xining; measuring 8.6 on the Richter scale, it also resulted in 200,000 deaths. Other earthquakes that have caused an extreme loss of life in the same decade include the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, which killed 143,000 in Tokyo in 1923.

The 2008 Sichuan earthquake had the same measurement on the Richter scale at 8.0 in magnitude. It, however, occurred in a mountainous region where relief efforts were noticeably hampered by the geographical makeup of the land nearby. The Sichuan earthquake also had a much quicker and more organized response system than Tangshan, as the political, social and technological environment was different. The Chinese government allowed international aid and open media access to the disaster area.

Cultural references

Personal accounts of the earthquake are related by two characters in Xinran's debut novel, The Good Women of China (2002), and addressed in Liu Zongren's book about the Cultural Revolution from a Beijing resident's perspective called 6 Tanyin Alley.

Chinese director Feng Xiaogang's 2010 film Aftershock gives a dramatic account about this tragic earthquake.

The 2011 Malaysian television series Tribulations of Life wrote it into the plot for one of its episodes, to reinforce the setting of it during the 70's, and used it as a storyline where villagers showed their charitable side.

In Johnathan Maberry's novel, The Extinction Machine, released in March 2013, the 1976 Tangshan earthquake is mentioned in part of the plot.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Zschau, Jochen. Küppers, Andreas N. [2003] (2003). Early Warning Systems for Natural Disaster Reduction. ISBN 3-540-67962-6

- 1 2 3 Spignesi, Stephen J. [2005] (2005). Catastrophe!: The 100 Greatest Disasters of All Time. ISBN 0-8065-2558-4

- ↑ Palmer p. 236

- 1 2 3 Stoltman, Joseph P. Lidstone, John. Dechano, M. Lisa. [2004] (2004). International Perspectives On Natural Disasters. Springer publishing. ISBN 1-4020-2850-4

- ↑ http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs4/Pelling-Disasters-1.pdf

- 1 2 Roza, Greg. [2007] (2007). Earthquake: True Stories of Survival. The Rosen Publishing. ISBN 1-4042-0997-2

- ↑ Rosenberg, Jennifer. "Tangshan: The Deadliest Earthquake". About.com. Accessed 2009-09-30. Archived 2009-10-02.

- ↑ "State Council Document No. 69". Archived from the original on 2009-10-02. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

- ↑ News.bbc.co.uk on this day 4132109

- ↑ Pickering, Kevin T. Owen, Lewis A. [1997] (1997). An Introduction to Global Environmental Issues. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14099-4.

- ↑ Theodore S. Glickman. [1993] (1993). Acts of God and Acts of Man. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 1-56806-371-7

- 1 2 3 Spence, Jonathan. [1991] (1991). The Search for Modern China. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30780-8

- ↑ Palmer, Ch.6, "I Live, You Die," Heaven Cracks, Earth Shakes describes these events.

- ↑ Palmer, p. 189, quoting from Jiaqi Yan,Gao Gao translated and edited by D.W.Y. Kwok., Turbulent Decade a History of the Cultural Revolution (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1996), p. 514.

- ↑ Palmer p. 191

- ↑ neic.usgs.gov

Further reading

- Qian Gang. The Great China Earthquake. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1989. ISBN 7-119-00565-0.

- James Palmer. Heaven Cracks, Earth Shakes: The Tangshan Earthquake and the Death of Mao's China. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2011. ISBN 978-0-465-01478-1 (hardcover alk. paper) 9780465023493 (ebk. alk. paper).

- Translation of the report on The Great Tangshan Earthquake of 1976 Prepared by Earthquake Engineering Laboratory California Institute of Technology, 2002.

External links

- "Tangshan: The Deadliest Earthquake" at About.com

- "Integration of Public Administration and Earthquake Science: The Best Practice Case of Qinglong County" at GlobalWatch.org

- 1976: Chinese earthquake kills hundreds of thousands (BBC, "On this day", 28 July)