20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Estonian)

| 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Estonian) | |

|---|---|

|

Divisional insignia of 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Estonian) | |

| Active | 24 January 1944 – 9 May 1945 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Defending the territory of Estonia |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps |

| Nickname(s) | Estonian Division |

| Motto(s) | Varemeist tõuseb kättemaks! (Vengeance Will Rise from the Ruins!) |

| Colors | Blue, Black & White |

| March | The Song of Estonian Legionaires |

| Engagements |

Battle of Narva 1944 Battle of Tannenberg Line 1944 Battle of Tartu 1944 Vistula-Oder Offensive 1945 Battle of Oppeln 1945 |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Franz Augsberger |

| Insignia | |

| Flag of the division |

|

| Collar insignia |

|

20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Estonian) (German: 20.Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS (estnische Nr.1), Estonian: 20. eesti diviis[1]) was a unit of the Waffen SS established on 25 May 1944 in German-occupied Estonia during World War II. Formed in Spring 1944 after the general conscription-mobilization was announced in Estonia on 31 January 1944 by the German occupying authorities, the cadre of the 3rd Estonian SS Volunteer Brigade, renamed the 20th Estonian SS Volunteer Division on 23 January 1944, was returned to Estonia and reformed. Additionally 38,000 men were conscripted in Estonia and other Estonian units that had fought on various fronts in the German Army, and the Finnish Infantry Regiment 200 were rushed to Estonia.

Estonian officers and men in other units that fell under the conscription proclamation and had returned to Estonia had their rank prefix changed from "SS" to "Waffen" (Hauptscharführer would be referred to as a Waffen-Hauptscharführer rather than SS-Hauptscharführer). The wearing of SS runes on the collar was forbidden, and these formations began wearing national insignia instead.

The Division fought the Red Army on the Eastern Front and surrendered in May 1945.

Historical context

On 16 June 1940, the Soviet Union had invaded Estonia.[2] The military occupation was complete by 21 June 1940 and rendered "official" by a communist coup d'état supported by Soviet troops and the Nazi government under the 23 August 1939 agreement signed in Moscow between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union as a Treaty of Non-Aggression. A secret protocol of the pact defined domains of influence, with the Soviet Union gaining eastern Poland, Finland, Latvia, Estonia and the Romanian province of Bessarabia. Germany was to control western Poland and Lithuania.[3]

After Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, the Germans were perceived by most Estonians as liberators from the USSR and its repression, and hopes were raised for the restoration of the country's independence. The initial enthusiasm that accompanied the liberation from Soviet occupation quickly waned as Estonia became a part of the German-occupied "Reichskommissariat Ostland".

By January 1944, the front was pushed back by the Red Army almost all the way to the former Estonian border. On 31 January 1944 general conscription-mobilization was announced in Estonia by the German authorities.[4] On 7 February Jüri Uluots, the last constitutional prime minister of the republic of Estonia,[5] supported the mobilization call during a radio address in the hope of restoring the Estonian Army and the country's independence.[nb 1] 38,000 men were conscripted, the formation of the 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Estonian) had begun.[7]

Formation

The 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS was formed in January 1944 via general conscription, from a cadre drawn on the 3. Estnische SS Freiwilligen Brigade, and further troops from the Ost Battalions and the 287th Police Fusilier Battalion and the returned Estonian volunteers of the Finnish army unit 200.[8][9][10]

Defence of Estonia

After the Soviet Kingisepp–Gdov Offensive, the division was ordered to be replaced on the Nevel front and transported to the Narva front, to defend Estonia.

The arrival of the I.Battalion, 1st Estonian Regiment at Tartu coincided with the prepared landing operation by the left flank of the Leningrad Front to the west coast of Lake Peipus, 120 kilometres south of Narva.[11] The I.Battalion, 1st Estonian Regiment was placed at the Yershovo Bridgehead on the east coast of Lake Peipus. Estonian and German units cleared the west coast of Peipsi of Soviets by 16 February. Soviet casualties were in thousands.[12]

Battle of Narva

On 8 February 1944, the division was attached to Gruppenführer Felix Steiner's III SS (Germanic) Panzer Corps, then defending the Narva bridgehead. The division was to replace the remnants of the 9th and 10th Luftwaffe Field Divisions, which were struggling to hold the line against a Soviet bridgehead north of the town of Narva. Upon arriving at the front on 20 February, the division was ordered to eliminate the Soviet bridgehead. In nine days of heavy fighting, the division pushed the Soviets back across the river and restored the line. The division remained stationed in the Siivertsi and Auvere sectors, being engaged in heavy combat.

In May, they were pulled out of the front line and reformed with the recently returned Narwa battalion into the division as the reconnaissance battalion. By that time, active conscription of Estonian men into the German armed forces was well under way. By Spring 1944, approximately 32,000 men were drafted into the German forces, with the 20th Waffen Grenadier Division consisting of some 15,000 men.

Battle of Tannenberg Line

When Steiner ordered a withdrawal to the Tannenberg Line on 25 July, the division was deployed on the Lastekodumägi Hill, the first line of defence for the new position. Over the next month, the division was engaged in a heavy defensive battle in the Sinimäed hills.

On 26 July, pursuing the withdrawing defenders, the Soviet attack fell onto the Tannenberg Line. The Soviet Air Force and artillery bombarded the German positions, destroying most of the forest on the hills.[11][13] On the morning of 27 July, the Soviet forces launched another powerful artillery barrage on the Sinimäed.

The heaviest Soviet attack took place on 29 July. By noon, the Red Army had almost seized control of the Tannenberg Line. The last reserve on the front, I.Battalion, 1st Estonian Regiment had been spared from the previous counterattacks. The scarcity of able-bodied men forced Sturmbannführer Paul Maitla to request reinforcements from patients in the field hospital. Twenty injured men responded, joining the remmnants of other units including a part of the Kriegsmarine and supported by the single remaining Panther tank.[13] The counterattack started from the parish cemetery south of the Tornimägi with the left flank of the assault clearing the hill of Soviet soldiers. The attack continued towards the summit under heavy Soviet artillery and bomber attack, culminating in close combat on the Soviet positions. The Estonian troops moved into the trenches. Running out of ammunition, they used Soviet grenades and automatic weapons taken from the fallen.[13] According to some veterans, it appeared that low-flying Soviet bombers were attempting to hit every individual Estonian soldier moving between craters, some of them getting buried under soil from the explosions of Soviet shells.[14] The Soviets were forced to retreat from the Grenaderimägi Hill.[11] The battle took many casualties in the division, including Sturmbannführer Georg Sooden who was killed on 28 July and Hauptsturmführer Oskar Ruut on 3 August.

Battle of Tartu

In mid-August, the division's 45th Estland and 46th regiments were formed into the Kampfgruppe Vent and sent south to help defend the Emajõgi river line, seeing heavy fighting.

At the end of August, the III.Battalion, 1st Estonian Regiment was formed from the 1st Battalion of the Finnish Infantry Regiment 200 recently returned to Estonia. As their largest operation, supported by Estonian Police Battalions No. 37, 38 and Mauritz Freiherr von Strachwitz's tank squadron, they destroyed the bridgehead of two Soviet divisions and recaptured Kärevere Bridge by 30 August. The operation shifted the entire front back to the southern bank of the Emajõgi and encouraged the II Army Corps to launch an operation attempting to recapture Tartu. The attack of 4–6 September reached the northern outskirts of the city but was repulsed by units of the Soviet 86th, 128th, 291st and 321st Rifle Divisions. Relative calm settled on the front for the subsequent thirteen days.[11]

Withdrawal from Estonia

When Adolf Hitler authorised the full withdrawal from Estonia in mid September, all men who wished to stay to defend their homes were released from service. Many chose this offer, fighting the Soviets alongside other Estonian units and then withdrawing into the forests to become the Forest Brothers (insurgents). Severely weakened by this, the division was withdrawn to Neuhammer to be refitted.

On 19 September 1944 the liquidation of the Klooga concentration camp, proximate to the division's training camp started. Approximately 2,500 prisoners from the Vaivara camp complex had been brought there in the course of the evacuation. The training and replacement units of the division based at Klooga under the command of Sturmbannführer Georg Ahlemann provided guards for the perimeters.[11][15]

Final battles

Eventually, the reformed division, which numbered roughly 11,000 Estonians and 2,500 Germans, returned to the front line in late February, just in time for the Soviet Vistula-Oder Offensive.[16] This offensive forced the German forces back behind the Oder and Neisse rivers. The division was pushed back to the Neisse, taking heavy casualties. The division was then trapped with the XI. Armeekorps in the Oberglogau - Falkenberg Niemodlin area in Silesia. On 17 March 1945, the division launched a major escape attempt, which despite making headway, failed. On 19 March, the division tried again, this time succeeding, but leaving all heavy weapons and equipment behind in the pocket.[17]

In April, the remnants of the division were moved south to the area around Goldberg. After the Prague Offensive, the division attempted to break out to the west, in order to surrender to the western Allies.[13] The Czech partisans resumed their hostilities on the surrendered Estonian troops regardless of their intentions. In what veterans of the Estonian Division who had laid their weapons down in May 1945 recall as the Czech Hell, the partisans chased, tortured and humiliated the Waffen SS men and murdered more than 500 Estonian POWs.[11][18][19] Some of the Estonians who had reached the western allies were handed back to the Soviets.[13]

Aftermath

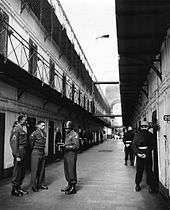

Guard duty during the Nuremberg Trials

In the spring of 1946, out of the ranks of those who had surrendered to the Western allies in the previous year, a total of nine companies were formed. One of these units, the 4221st Guard Company, formed from some 300 men on 26 December 1946, guarded the external perimeter of the Nuremberg International Tribunal courthouse and the various depots and residences of US officers and prosecutors connected with the trial. The men also guarded the accused Nazi war criminals held in prison during the trial, up until the day of execution.[13][20]

Outcome of Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg Trials, in declaring the Waffen SS a criminal organization, explicitly excluded conscripts in the following terms:

Tribunal declares to be criminal within the meaning of the Charter the group composed of those persons who had been officially accepted as members of the SS as enumerated in the preceding paragraph who became or remained members of the organization with knowledge that it was being used for the commission of acts declared criminal by Article 6 of the Charter or who were personally implicated as members of the organization in the commission of such crimes, excluding, however, those who were drafted into membership by the State in such a way as to give them no choice in the matter, and who had committed no such crimes.[21]

Position of the US Displaced Persons Commission

On 13 April 1950, a message from the Allied High Commission (HICOG), signed by John J. McCloy to the Secretary of State, clarified the US position on the "Baltic Legions: "they were not to be seen as "movements", "volunteer", or "SS." In short, they had not been given the training, indoctrination, and induction normally given to SS members.[22] Subsequently, the US Displaced Persons Commission in September 1950 declared that:

The Baltic Waffen SS Units (Baltic Legions) are to be considered as separate and distinct in purpose, ideology, activities, and qualifications for membership from the German SS, and therefore the Commission holds them not to be a movement hostile to the Government of the United States.

Commemoration and controversy

Most living veterans of the division belong to the 20th Estonian Waffen Grenadier Division Veterans Union (Estonian: 20. Eesti Relvagrenaderide Diviisi Veteranide Ühendus). It was founded in 2000 and gatherings of veterans of the division are organised by the union on the anniversaries of the battle of the Tannenberg Line in the Sinimäed hills. Since 2008, the chairman of the union, Heino Kerde, is a former member of the 45th Regiment.

In 2002, the Estonian government forced the removal of a monument to Estonian soldiers erected in the Estonian city of Pärnu. The inscription To Estonian men who fought in 1940-1945 against Bolshevism and for the restoration of Estonian independence was the cause of the controversy. The monument was rededicated in Lihula in 2004 but was soon removed because the Estonian government opposed the opening. On 15 October 2005 the monument was finally moved to the grounds of the Museum of Fight for Estonia's Freedom in Lagedi near the Estonian capital, Tallinn.

On 28 July 2007, a gathering of some 300 veterans of the 20th Waffen-Grenadier-Division and of other units of the Wehrmacht, including a few Waffen SS veterans from Austria and Norway, took place in Sinimäe, where the battle between the German and Soviet armies had been particularly fierce. This gathering takes place every year and has seen veterans from Estonia, Norway, Denmark, Austria and Germany attending.[23]

Commanders

- SS-Brigadeführer Franz Augsberger (24 January 1944 – 19 March 1945)

- SS-Standartenführer Alfons Rebane (temporarily during the Battle of Oppeln)

- SS-Brigadeführer Berthold Maack (20 March 1945 – 8 May 1945)

Division units

- Waffen-Grenadier Regiment der SS 45 Estland (estnische nr. 1) SS-Obersturmbannführer Harald Riipalu

- 1st Battalion – SS-Hauptsturmführer Paul Maitla

- 2nd Battalion – SS-Hauptsturmführer Ludvig Kiisk

- 3rd Battalion was still in the process of forming

- Waffen-Grenadier Regiment der SS 46 (estnische nr. 2) SS-Standartenführer Juhan Tuuling

- 1st Battalion – SS-Hauptsturmführer Heino Rannik

- 2nd Battalion – SS-Sturmbannführer Friedrich Kurg

- 3rd Battalion – SS-Obersturmführer Arseni Korp. The battalion was based on the 660th Ost battalion.

- Waffen-Grenadier Regiment der SS 47 (estnische nr. 3) SS-Obersturmbannführer Paul Vent

- 1st Battalion – SS-Sturmbannführer Georg Sooden. The battalion was based on the 659th Ost battalion.

- 2nd Battalion – SS-Hauptsturmführer Alfons Rebane. The battalion was based on the 658th Eastern Battalion.

- 3rd Battalion – SS-Hauptsturmführer Eduard Hints. Formed from mobilized men and was at this moment just arriving at the front.

- Waffen-Artillery Regiment der SS 20 - SS-Obersturmbannführer Aleksandr Sobolev.

- SS-Waffen Füsilier Battalion 20 - SS-Hauptsturmführer Wallner, SS-Obersturmbannführer Oskar Ruut, SS-Hauptsturmführer Hando Ruus

- SS-Waffen Pionier Battalion 20

- SS-Field Medical Battalion 20

- SS-Waffen Signals Battalion 20

- SS-Training and Reserve Regiment 20

Notable members

- Alfons Rebane, Estonian officer and Knight's Cross with Oakleaves recipient

- Paul Maitla, Estonian officer and Knight's Cross recipient

- Harald Riipalu, Estonian officer and Knight's Cross recipient

- Harald Nugiseks, Estonian officer and Knight's Cross recipient

- Kalju Lepik, Estonian poet

- Kaljo Kiisk, Estonian film director

- Artur Rinne, Estonian singer

- Arved Viirlaid (formerly in Finnish Regiment 200), Estonian writer

Weapons

Infantry weapons

-

.svg.png) Karabiner 98k

Karabiner 98k -

.svg.png) MaschinenPistole 40 (MP 40)

MaschinenPistole 40 (MP 40) -

.svg.png) SturmGewehr 44 (StG 44)

SturmGewehr 44 (StG 44) -

.svg.png) Panzerschreck

Panzerschreck -

.svg.png) Panzerfaust

Panzerfaust -

.svg.png) Pistole P08 (Luger P08)

Pistole P08 (Luger P08) -

.svg.png) SIG 33

SIG 33 -

.svg.png) MaschinenGewehr 34 (MG 34)

MaschinenGewehr 34 (MG 34) -

.svg.png) MaschinenGewehr 42 (MG 42)

MaschinenGewehr 42 (MG 42)

Vehicles

See also

- 3rd Estonian SS Volunteer Brigade

- List of Knight's Cross recipients 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS

- Estonian Regiment "Reval"

- Estonian Legion

- Grenadier, Waffen-SS

- Wehrmacht, List of German military units of World War II

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ In Estonia, the pre-war Prime minister Uluots switched his stand on mobilization in February 1944 when the Soviet Army reached the Estonian border. At the time the Estonian units under German control had about 14,000 men. Counting on a German debacle, Uluots considered it imperative to have large numbers of Estonians armed, through any means. Uluots even managed to tell it to the nation through the German-controlled radio: Estonian troops on Estonian soil have "a significance much wider than what I could and would be able to disclose here". The nation understood and responded. 38,000 registered. Six border-defense regiments were formed, headed by Estonian officers, and the SS Division received reinforcements, bringing the total of Estonian units up to 50,000 or 60,00 men. During the whole period at least 70,000 Estonians joined the German army, more than 10,000 may have died in action, about 10,000 reached the West after the war ended.[6]

- Citations

- ↑ Saksa okupatsioon (1941–44). Eesti. Üld. Eesti entsüklopeedia 11 (2002). pp. 312–315

- ↑ Five Years of Dates at Time magazine on Monday, 24 Jun. 1940

- ↑ Estonia: Identity and Independence by Jean-Jacques Subrenat, David Cousins, Alexander Harding, Richard C. Waterhouse ISBN 90-420-0890-3

- ↑ mobilisation in Estonia at estonica.org

- ↑ Jüri Uluots Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. at president.ee

- ↑ Misiunas, p. 60

- ↑ Jurado, p 13

- ↑ Jurado, pp 14-15

- ↑ "1940–1992. Soviet era and the restoration of independence". History Estonica. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- ↑ "Waffen SS". Jewish Virtual Library.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Toomas Hiio (2006). "Combat in Estonia in 1944". In Toomas Hiio; Meelis Maripuu; Indrek Paavle. Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Tallinn. pp. 1035–1094.

- ↑ Harald Riipalu (1951). Kui võideldi kodupinna eest (When Home Ground Was Fought For) (in Estonian). London: Eesti Hääl.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mart Laar (2006). Sinimäed 1944: II maailmasõja lahingud Kirde-Eestis (Sinimäed 1944: Battles of World War II in Northeast Estonia) (in Estonian). Tallinn: Varrak.

- ↑ A.Aasmaa (1999). Tagasivaateid.(Looking Back. In Estonian) In: Mart Tamberg (Comp.). Eesti mehed sõjatules. EVTÜ, Saku

- ↑ Birn, Ruth Bettina (2008). "Klooga". In Benz, Wolfgang; Distel, Barbara; Königseder, Angelika. Der Ort des Terrors. Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager (in German). 3. Munich: C.H.Beck. pp. 161–167 [164]. ISBN 978-3-406-52960-3. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

...das mit Hilfe von Angehörigen der 20. Waffen-SS Division unter dem Befehl des Kommandeurs der Ausbildungs- und Ersatzeinheiten, Georg Ahlemann, abgeriegelt wurde. (...with the help of members of the 20th Waffen-SS Division [and] under the orders of the commander of the training and replacement units, Georg Ahlemann, was sealed off.)

- ↑ Buttar, Prit (2013). Between Giants: The Battle for the Baltics in World War II. Osprey Publishing. p. 177. ISBN 9781780961637.

- ↑ Gunter pp. 221-237

- ↑ (Estonian) Karl Gailit (1995). Eesti sõdur sõjatules. (Estonian Soldier in Warfare.) Estonian Academy of National Defense Press, Tallinn

- ↑ Estonian State Commission on Examination of Policies of Repression (2005). "Human Losses". The White Book: Losses inflicted on the Estonian nation by occupation regimes. 1940–1991 (PDF). Estonian Encyclopedia Publishers. p. 32.

- ↑ "Esprits de corps - Nuremberg Tribunal Guard Co. 4221 marks 56th anniversary". Eesti Elu.

- ↑ Nuremberg Trial Proceedings, Volume 22, September 1946

- ↑ Mirdza Kate Baltais, The Latvian Legion in documents, Amber Printers & Publishers (1999), p104

- ↑ Official Estonia, Latvia Call Up Waffen SS Vets

References

- Nigel Thomas; Caballero Jurado (2002). Germany's Eastern Front allies (2): Baltic forces. Darko Pavlovic. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-193-1.

- Jurs, August - Estonian freedomfighters in World War II

- Misiunas, Romuald; Rein Taagepera (1993). The Baltic States, Years of Dependence, 1940-1990. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08228-1.

- Wendel, Marcus (2005). "20. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS (estnische Nr.1)". Retrieved 2 June 2005.

- "20. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS (estnische Nr.1)". German language article at www.lexikon-der-wehrmacht.de. Retrieved 2 June 2005.

- Conclusions of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity - Phase II: The German occupation of Estonia in 1941–1944

- Georg Gunter, Duncan Rogers, Last Laurels: The German Defence of Upper Silesia, January–May 1945, Helion & Co., 2002, ISBN 1-874622-65-5.