30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS

| 30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS | |

|---|---|

|

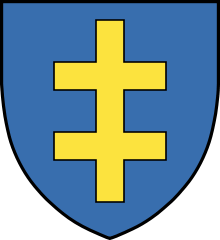

Insignia of the second formation of the 30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (ethnically designated as "1st White Ruthenian") | |

| Active | 1 August 1944 – 15 April 1945 |

| Country |

|

| Allegiance | Adolf Hitler |

| Branch | Waffen SS |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Colors | White, Red, and White |

The 30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (German: 30. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS) was a German Waffen SS infantry division formed largely from Belarusian, Russian and Ukrainian personnel of the Schutzmannschaft-Brigade Siegling in August 1944 at Warsaw, Poland.[1] The division was moved by rail to southeastern France by mid-August 1944 to combat the French Forces of the Interior (FFI). The division's performance in combat was poor, and two battalions mutinied, murdered their German leaders, and defected to the FFI. Other troops of the division crossed the Swiss border and were interned. The remainder of the division saw little subsequent combat and eventually relocated in January 1945 to Grafenwöhr, a large military training camp north of Nuremberg. Finally, some of the division's personnel were transferred to the Russian Liberation Army while others were retained to form the SS "White Ruthenian" infantry brigade from January 1945.[2] This brigade in its turn was retitled as the 30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS in March 1945, but was disbanded in April 1945 before the unit saw combat.

Formation and initial organization

On 31 July 1944 orders were issued to form a division from the personnel of the Schutzmannschaft-Brigade Siegling, who were subsequently organized into four infantry regiments (numbered 1 through 4). The initial organization of the division also included an artillery battalion, a cavalry battalion, and a training battalion.[3] At this time, the division's full name was 30. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS (russische Nr. 2). The term "Waffen-Grenadier" was used to denote SS infantry divisions manned by personnel of other-than-German ethnicity.

At the end of August 1944, division strength was estimated as 11,600 with the bulk originating from Belarus. The leadership cadre of the division was primarily German.

In mid-August 1944, the division was moved by rail to southeastern France in the region of Belfort and Mulhouse. By October, the organization of the division had been altered to three infantry regiments of three battalions each, a motorcycle (reconnaissance) battalion, an artillery battalion, and a field replacement battalion.[4] The artillery battalion consisted of two batteries of captured 122-mm Soviet artillery pieces.[5]

Mutiny and desertion

Elements of the division arrived in Vesoul on 20 August 1944 and were charged with the security of the Belfort Gap, particularly against operations conducted by the French Forces of the Interior (FFI). The same day, other elements of the division occupied the area around Camp Valdahon, about thirty kilometers southeast of Besançon.[6]

Subsequent events proved the division had serious issues of disaffection and even outright disloyalty to the Nazi cause. On 27 August 1944, under the direction of Major Lev (Leon) Hloba, a Ukrainian battalion of the division at Vesoul shot their German leadership cadre and defected to an FFI unit in the Confracourt Woods, bringing 818[7] men, 45-mm antitank guns, 82-mm and 50-mm mortars, 21 heavy machine guns, as well as large amounts of small arms and small-caliber ammunition.[8] A similar defection occurred the same day near Camp Valdahon and brought over hundreds of men, one antitank gun, eight heavy machine guns, four mortars, and small arms and ammunition.[9] The defectors were subsequently inducted into the FFI as the 1st and 2nd Ukrainian Battalions and many were later amalgamated into the 13th Demi-Brigade of Foreign Legion, itself subordinated to the 1st Free French Division.[10]

On 29 August 1944, the first and third battalions of the division's 4th Regiment deserted and crossed the border into Switzerland.[11]

On 2 September, two squadrons (companies) of the division's cavalry battalion (formerly Kosaken-Schuma-Abteilung 68 and redesignated the Waffen-Reiter-Abteilung der SS 30)[12] were surrounded and destroyed in a surprise attack at Melin by the Ukrainians who had defected in the Confracourt Woods.[13]

The subsequent investigation of these events by German authorities resulted in some 2,300 men in the division being deemed "unreliable".[14] As punishment, these personnel were transferred to two field entrenchment construction regiments (German: Schanzregiment) subordinated to the Karlsruhe Transport Commandant, leaving some 5,500 men still in the division.[15] The extraordinary events in the division also led to it being placed in Army Group G reserve[16] and being viewed by senior German leadership in Alsace as an unreliable unit.[17]

On 24 October 1944, the division had reorganized into three regiments, numbered 75 to 77, each of two infantry battalions. This organization accorded with the orders for formation of the division that had been issued in August 1944 by the SS Führungshauptamt. Because of losses, however, the 77th Regiment was disbanded on 2 November.[18]

Combat

The success of the French breakthrough in the Belfort Gap starting on 13 November 1944 created a crisis in the German defenses from Belfort to Mulhouse. With defending units under severe pressure by the French advance, the Germans committed the 30th SS Division to counterattack the French attack at Seppois. The advance of the SS division on 19 November reached a point roughly a mile north of Seppois, but was held there and pushed back by French counterattacks.[19] The division then went on the defensive in the area around Altkirch.

As the German situation in lower Alsace solidified into what would become known as the Colmar Pocket, the 30th SS Division remained in the German front line north of Huningue and west of the Rhine River.[20] In late December 1944, with its manpower down to 4,400 men, the division was withdrawn from the front and ordered to the Grafenwöhr training area deep inside of Germany.[21]

Disbandment and second formation

Orders to disband the division were issued on 1 January 1945, and the division arrived at Grafenwöhr on 11 January. Russian personnel in the division were transferred to the 600th Infantry Division, a unit of Russians organized by Nazi Germany and belonging to the Russian Liberation Army.[22]

On 15 January 1945, the non-Russian personnel of the division were organized into the 1st White Ruthenian SS Grenadier Brigade, a unit that had only a single regiment of infantry (the 75th) with three battalions as well as some other units such as an artillery battalion and a cavalry battalion. While still organizing, the brigade was retitled the 30th SS Grenadier Division (1st White Ruthenian) (German: 30. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS (weissruthenische Nr. 1)) on 9 March 1945, but it still had only a single regiment of infantry. Finally, in April 1945, this iteration of the division was also disbanded, with the German cadre being sent to the 25th and 38th SS Grenadier Divisions.[23]

Ethnic composition

Although part of the German forces, the division's German cadre was always only a small part of the unit's strength with the bulk of the personnel originating from (current) Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine.

Known war crimes

Soldiers of the division together with an unspecified Italian unit killed 40 civilians in Étobon, France on 27 September 1944, in retaliation of the support given by villagers to the French partisans. An additional 27 were taken from the village to Germany; of them seven were shot ten days later.[24]

Order of battle

As planned on August 1, 1944:

- 75th SS Grenadier Regiment with two battalions

- 76th SS Grenadier Regiment with two battalions

- 77th SS Grenadier Regiment with two battalions

- 30th SS Reconnaissance Battalion

- 30th SS Artillery Regiment with two battalions

- Rear service regiment

- Pionier Company,

- Signals Company

- Training Battalion

As of September 12, 1944:

- 1st Regiment

- 2nd Regiment

- Battalion "Murawjew"

- Training Battalion

As of October 24, 1944:

- 75th SS Grenadier Regiment

- 76th SS Grenadier Regiment

- 77th SS Grenadier Regiment

- 30th SS Artillery Battalion

- 30th SS Reconnaissance Battalion

- 30th SS Pioneer Company

- 30th SS Signals Company

- 30th SS Medical Company

- 30th SS Field Hospital Battalion

As of November 2, 1944:

- 75th SS Grenadier Regiment

- 76th SS Grenadier Regiment

Insignia

The symbol chosen was a horizontally-turned Patriarchal cross with two bars equal in length and parallel to each other, which likely represents the Cross of Saint Euphrosyne and the central element of the medieval coat of arms of the Belarusian and Lithuanian lands -- the Pahonia (the Jagellon cross).[25] After January 29, 1945, a white-red-white stripe on right side was adopted with the phrase "Weissruthenien" (White Ruthenia) emblazoned.

In 1974, Belarusian immigrants erected a monument in South River, New Jersey honoring "those who fought for the freedom and independence" of Belarus, featuring the Pahonia and the double bar cross (not horizontally-turned, unlike as on the insignia of the SS Division) on the top. The monument does not mention the SS division in any way but some writers not related to the Belarusian community claim that the symbol represents its insignia.[26][27]

See also

References

- ↑ Nafziger, p. 131

- ↑ Tessin, p. 291

- ↑ Tessin and Kannapin, p. 105

- ↑ Tessin and Kannapin, p. 105

- ↑ Nafziger, p. 131

- ↑ Sorobey, Ron. "Ukrainians in France".

- ↑ http://forum.ottawa-litopys.org/france/sorobey.htm

- ↑ Sorobey

- ↑ Sorobey

- ↑ Sorobey

- ↑ zweiter-weltkrieg-lexicon.de

- ↑ panzer-archiv.de

- ↑ Sorobey

- ↑ Tessin, p. 291

- ↑ zweiter-weltkrieg-lexicon.de

- ↑ Tessin, p. 291

- ↑ Clarke and Smith, p. 411

- ↑ Tessin, Verbande, p. 291

- ↑ Clarke and Smith, p. 421

- ↑ Clarke and Smith, p. 485

- ↑ Tessin, Verbande, p. 291

- ↑ Tessin, p. 291

- ↑ Tessin, Verbande, p. 291

- ↑ Larousse

- ↑ Today, the symbol is widely used by the Belarusian Greek Catholic Church, the Belarusian Orthodox Church and in modern Lithuania (see Cross of Vytis).

- ↑ http://articles.latimes.com/1988-10-23/news/mn-237_1_nazi-collaborators

- ↑ http://www.stetson.edu/law/lawreview/media/remembering-the-holocust.pdf

Sources

- Jeffrey J. Clarke and Robert Ross Smith, Riviera to the Rhine, Washington: GPO, 1993.

- George Nafziger, The German Order of Battle Waffen SS and other units in World War II, Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 2001.

- Georg Tessin and Norbert Kannapin, Waffen-SS und Ordnungspolizei im Kriegseinsatz 1939-1945, Osnabrück: Biblio Verlag, 2000.

- Georg Tessin, Verbande und Truppen der deutschen Wehrmacht und Waffen SS im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945 Vierter Band: Die Landstreitkrafte 15—30 Frankfurt/Main: Verlag E. S. Mittler & Sohn GmbH, 1970.

External links

- Sorobey

- Ю. Грыбоўскі — Беларускі легіён СС: міфы і рэчаіснасць

- «Белорусские коллаборационистские формирования в эмиграции (1944-1945): Организация и боевое применение» // Романько О.В. Коричневые тени в Польсье. Белоруссия 1941-1945. М.: Вече, 2008.