Constitution of May 3, 1791

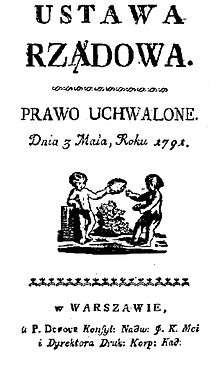

| Ustawa Rządowa | |

|---|---|

|

Page one of the original copy of the Constitution | |

| Created | October 6, 1788 – May 3, 1791 |

| Ratified | May 3, 1791 |

| Location | Central Archives of Historical Records, Warsaw |

| Author(s) | |

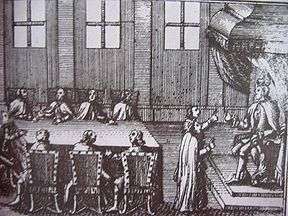

Foreground: King Stanisław August (left) enters St John's Collegiate Church where deputies will swear to uphold the Constitution. Background: the Royal Castle where the Constitution has just been adopted

The Constitution of 3 May 1791 (Polish: Konstytucja 3 maja, Lithuanian: Gegužės trečiosios konstitucija) was adopted by the Great Sejm (parliament) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a dual monarchy comprising Poland and Lithuania. Drafted over 32 months beginning on 6 October 1788, and formally adopted as the Government Act (Ustawa rządowa), the document was designed to redress the Commonwealth's political defects. The system of Golden Freedoms, also known as the "Nobles' Democracy", had conferred disproportionate rights on the nobility (szlachta) and over time had corrupted politics. The adoption of the Constitution was preceded by a period of agitation for—and gradual introduction of—reforms beginning with the Convocation Sejm of 1764 and the election of Stanisław August Poniatowski as the Commonwealth's last king.

The constitution sought to supplant the prevailing anarchy fostered by some of the country's magnates with a more democratic constitutional monarchy. It introduced elements of political equality between townspeople and nobility, and placed the peasants under the protection of the government, thus mitigating the worst abuses of serfdom. It banned parliamentary institutions such as the liberum veto, which had put the Sejm at the mercy of any deputy who could revoke all the legislation that had been passed by that Sejm. The Commonwealth's neighbours reacted with hostility to the adoption of the constitution. Frederick William II's Kingdom of Prussia broke its alliance with the Commonwealth, which was attacked and then defeated in the War in Defence of the Constitution by an alliance between Catherine the Great's Imperial Russia and the Targowica Confederation of anti-reform Polish magnates and landless nobility. The King, a principal co-author, eventually capitulated to the Confederates.

The 1791 document remained in force for less than 19 months; it was annulled by the Grodno Sejm on 23 November 1793. By 1795, the Second and Third Partitions of Poland ended the existence of the sovereign Polish state. Over the next 123 years, the Constitution of 3 May, 1791, was seen as proof of successful internal reform and as a symbol promising the eventual restoration of Poland's sovereignty. In the words of two of its co-authors, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj, it was "the last will and testament of the expiring Country."[lower-alpha 1] British historian Norman Davies described the document as "the first constitution of its type in Europe"; others have called it the world's second-oldest codified national constitution after the 1789 U.S. Constitution.[2][3][4][5][lower-alpha 2]

Background

Polish constitutionalism can be traced to the 13th century, when government by consensus and representation was already well established in the young Polish state. The emergence of parliamentary bodies, the sejm and sejmiki, followed. By the 17th century, Poland's legal and political tradition was characterized by: parliamentary institutions and a system of checks and balances on state power, which was itself limited by decentralization; the idea of a contractual state, embodied in texts like the Henrician Articles and the Pacta conventa; the concept of individual liberties; and the notion that the monarch owed duties to his subjects. This system, which primarily benefited the Polish nobility (szlachta), came to be known as the "nobles' democracy".[7]

End of the Golden Age

The 1791 Constitution was a response to the increasingly perilous situation in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth,[8] which had been a major European power only a century earlier and was still the largest state on the continent.[9] In the 1590s, at the peak of the nobles' democracy, King Sigismund III Vasa's court preacher—the Jesuit Piotr Skarga—had condemned the weaknesses of the Commonwealth.[10] In the same period, writers and philosophers such as Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski[11] and Wawrzyniec Grzymała Goślicki,[12] and the egzekucja praw (Execution-of-the-Laws) reform movement led by Jan Zamoyski had advocated political reforms.[13] In 1656, Sigismund's son King John II Casimir Vasa made a solemn vow at the 'old' Lvov Cathedral on behalf of the entire Republic of Poland, that he would free the Polish peasants “from their unjust burdens and oppression.”[14] As he was struggling with the Sejm, in 1661 John Casimir—whose reign saw highly destructive wars and obstructionism by the nobility—correctly predicted that the Commonwealth was in danger of a partition by Russia, Brandenburg and Austria.[15]

As the Sejm failed to implement sufficient reforms, the state machinery became increasingly dysfunctional. A major cause of the Commonwealth's downfall was the liberum veto ("free veto"), which since 1652 had allowed any Sejm deputy to nullify all the legislation enacted by that Sejm.[7][16] As a result, deputies bribed by magnates or foreign powers—primarily from the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia and France—or deputies who believed they were living in an unprecedented "Golden Age" paralysed the Commonwealth's government for over a century.[7][16][17] The threat of the liberum veto could only be overridden by the establishment of a "confederated sejm", which was immune to the liberum veto.[18] Declaring that a sejm either constituted a "confederation" or belonged to one was a contrivance prominently used by foreign interests in the 18th century to force a legislative outcome.[19]

By the early 18th century, the magnates of Poland and Lithuania controlled the state, ensuring that no reforms that might weaken their privileged status (the "Golden Freedoms") would be enacted.[20] The ineffective monarchs who were elected to the Commonwealth throne in the early 18th century,[21] Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III of Poland of the House of Wettin, did not improve matters. The Wettins, used to the absolute rule practiced in their native Saxony, tried to govern through intimidation and the use of force, which led to a series of conflicts between their supporters and opponents—including another pretender to the Polish throne, King Stanisław Leszczyński.[21] Those conflicts often took the form of confederations—legal rebellions against the king permitted under the Golden Freedoms—including the Warsaw Confederation (1704), Sandomierz Confederation, Tarnogród Confederation, Dzików Confederation and the War of the Polish Succession.[21] Only 8 out of 18 Sejm sessions during the reign of Augustus II (1694–1733) passed legislation.[22] For 30 years during the reign of Augustus III, only one session was able to pass legislation.[23] The government was near collapse, giving rise to the term "Polish anarchy", and the country was managed by provincial assemblies and magnates.[23]

Other reform attempts in the Wettin era were led by individuals such as Stanisław Dunin-Karwicki, Stanisław A. Szczuka, Kazimierz Karwowski and Michał Józef Massalski; these mostly proved to be futile.[17][21]

Early reforms

The Enlightenment greatly influenced certain Commonwealth circles during the 1764–95 reign of its last king, Stanisław II August Poniatowski. Poniatowski was an "enlightened" Polish magnate who had been a deputy to several Sejms between 1750 and 1764 and had a deeper understanding of Polish politics than previous monarchs.[24] The Convocation Sejm of 1764, which elected Poniatowski to the throne, was controlled by the Czartoryski family's reformist Familia party and was backed up by Russian military forces, which the Czartoryskis invited.[25] In exchange for passing decrees favorable to them, the Russians and Prussians let the confederated Convocation Sejm enact a number of reforms, including the weakening of liberum veto and ensuring it no longer applied to treasury and economic matters.[24][25][26] A more comprehensive reform package was presented by Andrzej Zamoyski, but opposition from Prussia, Russia and the Polish nobility thwarted this ambitious program, which proposed to decide on all motions by majority voting.[25] In part because his election was imposed by Empress Catherine the Great, Poniatowski's political position was weak from the beginning. He proceeded with cautious reforms such as the establishment of fiscal and military ministries and the introduction of a national customs tariff, which was soon abandoned because of opposition from Frederick the Great of Prussia.[25] These measures had already been authorized by the Convocation Sejm; more legislative and executive improvements inspired by Familia or the King were implemented during and after the 1764 Sejm.[25]

The Commonwealth's magnates viewed reform with suspicion and neighboring powers, content with the deterioration of the Commonwealth, abhorred the thought of a resurgent and democratic power on their borders.[28] With the Commonwealth Army reduced to around 16,000, it was easy for its neighbors to intervene directly—the Imperial Russian Army numbered 300,000 and the Prussian Army and Imperial Austrian Army had 200,000 each.[29]

Russia's Empress Catherine and Prussia's King Frederick II provoked a conflict between members of the Sejm and the King over civil rights for religious minorities, such as Protestants and Greek Orthodox whose positions, which were guaranteed equal with the Catholic majority by the Warsaw Confederation of 1573, had worsened considerably.[26][30][31][32] Catherine and Frederick declared their support for the szlachta and their "liberties", and by October 1767 Russian troops had assembled outside Warsaw in support of the conservative Radom Confederation.[31][32][33] The King and his adherents had little choice but to acquiesce to Russian demands. During the Repnin Sejm (named after the unofficially presiding Russian ambassador Nicholas Repnin) the King accepted the five "eternal and invariable principles" which Catherine had vowed to "protect for all time to come in the name of Poland's liberties": the election of kings, the right of liberum veto, the right to renounce allegiance to and raise rebellion against the king (rokosz), the szlachta's exclusive right to hold office and land, and landowners' power over their peasants.[26][28][31][32] Thus all the privileges ("Golden Freedoms") of the nobility that had made the Commonwealth ungovernable were guaranteed as unalterable in the Cardinal Laws.[31][32][33] The Cardinal Laws and the rights of "religious dissenters" passed by the Repnin Sejm were personally guaranteed by Empress Catherine. By these acts of legislation, for the first time, Russia formally intervened in the Commonwealth's constitutional affairs.[34]

During the 1768 Sejm, Repnin showed his disregard for local resistance by arranging the abduction and imprisonment of Kajetan Sołtyk, Józef A. Załuski, Wacław Rzewuski and Seweryn Rzewuski, all vocal opponents of foreign domination and the recently proclaimed policies.[35] The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth had legally and practically become a protectorate of the Russian Empire.[36] Nonetheless, several minor beneficial reforms were adopted, political rights of the religious minorities were restored and the need for more reforms was becoming increasingly recognized.[32][35]

King Stanisław August's acquiescence to the Russian intervention encountered some opposition. On February 29, 1768, several magnates—including Józef Pułaski and his young son Kazimierz Pułaski (Casimir Pulaski)—vowing to oppose Russian influence, declared Stanisław August a lackey of Russia and Catherine, and formed a confederation at the town of Bar.[35][37][38] The Bar Confederation focused on limiting the influence of foreigners in Commonwealth affairs, and being pro-Catholic was generally opposed to religious tolerance.[37] It began a civil war to overthrow the King, but its irregular forces were overwhelmed by Russian intervention in 1772.[28]

The defeat of the Bar Confederation set the scene for the partition treaty of August 5, 1772, which was signed at Saint Petersburg by Russia, Prussia and Austria.[37] The treaty divested the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth of about a third of its territory and population—over 200,000 km2 (77,220 sq mi) and 4 million people.[39] The three powers justified their annexation, citing anarchy in the Commonwealth and its refusal to cooperate with its neighbors' efforts to restore order.[40] King Stanisław August yielded and on April 19, 1773, he called the Sejm into session. Only 102 of about 200 deputies attended what became known as the Partition Sejm. The rest were aware of the King's decision and refused. Despite protests from the deputy Tadeusz Rejtan and others, the treaty—later known as the First Partition of Poland—was ratified.[39]

The first of the three successive 18th-century partitions of Commonwealth territory that would eventually remove Poland's sovereignty shocked the Commonwealth's inhabitants and made it clear to progressive minds that the Commonwealth must either reform or perish.[39] In the thirty years before the Constitution, there was a rising interest among progressive thinkers in constitutional reform.[41] Before the First Partition, a Polish noble, Michał Wielhorski was sent to France by the Bar Confederation to ask the philosophes Gabriel Bonnot de Mably and Jean-Jacques Rousseau for their suggestions on a new constitution for a reformed Poland.[42][43][44][45][46] Mably submitted his recommendations Du gouvernement et des lois en Pologne (The Government and Laws of Poland) in 1770–71, whereas Rousseau finished his Considerations on the Government of Poland in 1772 when the First Partition was already underway.[47] Works advocating the need for reform and presenting specific solutions were published in the Commonwealth by Polish–Lithuanian thinkers: On an Effective Way of Councils or on the Conduct of Ordinary Sejms (1761–63), by Stanisław Konarski, founder of the Collegium Nobilium; Political Thoughts on Civil Liberties (1775) and Patriotic Letters (1778–78), by Józef Wybicki, author of the lyrics of the Polish National Anthem; (Anonymous Letters to Stanisław Małachowski (1788–89) and The Political Law of the Polish Nation (1790), by Hugo Kołłątaj, head of the Kołłątaj's Forge party; and Remarks on the Life of Jan Zamoyski (1787), by Stanisław Staszic.[45][48] Ignacy Krasicki's satires of the Great Sejm era were also seen as crucial to giving the constitution moral and political support.[49]

A new wave of reforms supported by progressive magnates such as the Czartoryski family and King Stanisław August were introduced at the Partition Sejm.[33][50][51] The most important included the 1773 establishment of the Commission of National Education (Komisja Edukacji Narodowej)—the first ministry of education in the world.[39][51][52][53] New schools were opened, uniform textbooks were printed, teachers received better education and poor students were provided with scholarships.[39][51] The Commonwealth's military was to be modernized and funding to create a larger standing army was agreed.[54] Economic and commercial reforms—including some intended to cover the increased military budget previously shunned as unimportant by the szlachta—were introduced.[50][51][54] A new executive assembly, the 36-strong Permanent Council comprising five ministries with limited legislative powers, was established, giving the Commonwealth a governing body in constant session between Sejms and therefore immune to their liberum veto disruptions.[33][39][50][51]

In 1776, the Sejm commissioned former chancellor Andrzej Zamoyski to draft a new legal code.[41] By 1780, he and his collaborators had produced the Zamoyski Code (Zbiór praw sądowych). It would have strengthened royal power, made all officials answerable to the Sejm, placed the clergy and their finances under state supervision, and deprived landless szlachta of many of their legal immunities. The Code would also have improved the situation of non-nobles—townspeople and peasants.[55] Zamoyski's progressive legal code, containing elements of constitutional reform, met with opposition from native conservative szlachta and foreign powers; the 1780 Sejm did not adopt it.[41][55][56]

Adoption

An opportunity for reform occurred during the "Great Sejm"—also called the "Four-Year Sejm"—of 1788–92, which began on October 6, 1788, with 181 deputies. In accordance with the Constitution's preamble, from 1790 it met "in dual number" when 171 newly elected deputies joined the earlier-established Sejm.[33][48][57] On its second day, the body became a confederated sejm to avoid the liberum veto.[48][58][59] Concurrent world events appeared to have been opportune for the reformers.[33] Russia and Austria were at war with the Ottoman Empire, and the Russians found themselves simultaneously fighting in the Russo-Swedish War, 1788–1790.[33][60][61][62] A new alliance between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Prussia seemed to provide security against Russian intervention, and King Stanisław August drew closer to leaders of the reform-minded Patriotic Party.[33][63][64]

The Sejm passed few major reforms in its first two years, but the subsequent two years brought more substantial changes.[59] The Sejm adopted the 1791 Free Royal Cities Act, which was formally incorporated into the final constitution. This act addressed a number of matters related to the cities, crucially expanding burghers' (i.e., townspeople's) rights, including electoral rights.[65][66] While the Sejm comprised representatives of the nobility and clergy, the reformers were supported by the burghers, who in late 1789 organized in Warsaw a "Black Procession" demanding full political enfranchisement of the bourgeoisie.[64] On 18 April 1791 the Sejm—fearing that the burghers' protests, if ignored, could turn violent, as they had in France not long before—adopted the Free Royal Cities Act.[67]

The new constitution was drafted by the King, with contributions from Ignacy Potocki, Hugo Kołłątaj and others.[33][49] The King is credited with writing the general provisions and Kołłątaj with giving the document its final shape.[49][59] Stanisław August wanted the Commonwealth to become a constitutional monarchy similar to that of Great Britain, with a strong central government based on a strong monarch.[59] Potocki wanted the Sejm to be the strongest branch of government. Kołłątaj wanted a "gentle" revolution, carried out without violence, to enfranchise other social classes in addition to the nobility.[59]

The proposed reforms were opposed by the conservatives, including the Hetmans' Party.[48][68] Threatened with violence by their opponents, the advocates of the draft began the debate on the Government Act two days early, while many opposing deputies were away on Easter recess.[69] The debate and subsequent adoption of the Government Act was executed as a quasi-coup d'état. No recall notices were sent to known opponents of reform, while many pro-reform deputies secretly returned early.[69] The royal guard under the command of the King's nephew Prince Józef Poniatowski were positioned about the Royal Castle, where the Sejm was gathered, to prevent opponents from disrupting the proceedings.[69] On May 3, the Sejm convened with only 182 members, about half its "dual" number.[66][69] The bill was read and overwhelmingly adopted, to the enthusiasm of the crowds outside.[70] A protest was submitted the next day by a small group of deputies, but on May 5 the matter was officially concluded and protests were invalidated by the Constitutional Deputation of the Sejm.[71] It was the first time in the 18th century that a constitutional act had been passed in the Commonwealth without the involvement of foreign powers.[71]

Soon after, the Friends of the Constitution (Zgromadzenie Przyjaciół Konstytucji Rządowej)—which included many participants in the Great Sejm—was organised to defend the reforms already enacted and to promote further ones. It is now regarded as the first modern-style political party in Poland's history.[49][72] The response to the new constitution was less enthusiastic in the provinces, where the Hetmans' Party enjoyed considerable influence.[70] General support among the middle nobility was crucial and still very substantial; most of the provincial sejmiks deliberating in 1791 and early 1792 supported the constitution.[73]

Features

The Polish constitution was one of several to reflect Enlightenment influences, in particular Rousseau's social contract and Montesquieu's advocacy of a separation and balance of powers between the three branches of government and his advocacy of a bicameral legislature.[7][33][46][74][75] Once the government was established, it aimed to ensure, in accordance with Article V, that "the integrity of the states, civil liberty, and social order shall always remain in equilibrium".[33][74][75] According to Polish-American historian Jacek Jędruch, the liberality of its provisions "fell somewhere below [those of] the French, above the Canadian, and left the Prussian far behind", but did not equal the American Constitution".[66] King Stanisław August Poniatowski said the new constitution was "founded principally on those of England and the United States of America, but avoiding the faults and errors of both, and adapted as much as possible to the local and particular circumstances of the country."[76] George Sanford said that the Polish constitution provided "a constitutional monarchy close to the English model of the time."[33]

Article I acknowledged the Roman Catholic faith as the "dominant religion", but guaranteed tolerance and freedom to all religions.[33][62] It was less progressive than the 16th-century Warsaw Confederation, and placed Poland clearly within the Catholic sphere of influence.[77] Article II confirmed many old privileges of the nobility, stressing that all nobles are equal and should enjoy personal security and the right to property.[78] Article III stipulated that the earlier Free Royal Cities Act (Miasta Nasze Królewskie Wolne w Państwach Rzeczypospolitej) of April 18 (or 21), 1791, was integral to the constitution. Personal security—neminem captivabimus, the Polish habeas corpus act—was extended to townspeople (including Jews). Townspeople also gained the right to acquire landed property and became eligible for military officers' commissions and public offices, such as reserved seats in the Sejm and seats in the executive commissions of the Treasury, the Police and the Judiciary.[7][67] Membership of the nobility was also made easier for burghers to acquire.[79]

With half a million burghers in the Commonwealth now substantially enfranchised, political power became more equally distributed, but little was done about the less politically conscious and active classes, such as the Jews and peasants.[60][77][78][80] Although Article IV placed the Commonwealth's peasantry under the protection of the national law—a first step toward enfranchising the country's largest and most oppressed social class—the low status of the peasantry as compared to other classes was not eliminated, as the constitution did not abolish serfdom.[78][80][81][lower-alpha 3] Not until the Second Partition and Kościuszko's Proclamation of Połaniec in 1794 would the Polish government begin to abolish serfdom.[83]

Article V stated that "all power in civil society [should be] derived from the will of the people."[7] The constitution referred to the country's "citizens", which for the first time in Polish legislation was meant to include townspeople and peasants, as well as nobles.[7][71] The document's preamble and 11 individual articles introduced the principle of popular sovereignty applied to the nobility and townspeople, and the separation of powers into legislative (a bicameral Sejm), executive ("the King and the Guardians", the Guardians of the Laws being the newly established top governmental entity) and judicial branches.[33][74][84] It advanced the democratization of the polity by limiting the excessive legal immunities and political prerogatives of landless nobility.[67][78][81][85]

Legislative power, as defined in Article VI, rested with the bicameral parliament (an elected Sejm and an appointed Senate) and the king.[81][86] The Sejm met "ordinarily" every two years and "extraordinarily" whenever required by a national emergency.[81][86] Its lower chamber—the Chamber of Deputies (Izba Poselska)—comprised 204 deputies (2 from each powiat, 68 each from the provinces of Greater Poland, Lesser Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) and 21 plenipotentiaries of royal cities (7 from each province).[33][81] The royal chancellery was to inform the sejmiks of the legislation it intended to propose in advance, so that the deputies would have time to prepare for the discussions.[86] The Sejm's upper chamber—the Chamber of Senators (Izba Senacka)—comprised between 130[81] and 132[33] (sources vary) senators (voivodes, castellans, and bishops, as well as governments ministers without the right to vote).[33][81] The Senate was presided over by the king, who had one vote which could be used to break ties.[81] The king and all deputies had legislative initiative, and most matters—known as general laws, and divided into constitutional, civil, criminal, and those for the institution of perpetual taxes—required a simple majority, first from the lower chamber, then from the upper one.[82] For the more specialized resolutions, such as for treaties of alliance, declarations of war and peace, ennoblements and increases in national debt, a majority vote of both chambers voting jointly was needed.[82] The Senate (but not the king) had a suspensive veto over the laws that the Sejm passed, applicable until the next Sejm session, when it could be overruled.[7][81]

Article VI also recognized the Prawo o sejmikach, the act on regional assemblies (sejmiks) that had been passed on March 24, 1791.[66][87] By reducing the enfranchisement of the noble classes, this law introduced major changes to the electoral ordinance.[65] Previously, all nobles had been eligible to vote in sejmiks, which de facto meant that many of the poorest, landless nobles—known as "clients" or "clientele" of local magnates—voted as the magnates bade them.[33][65] Now the voting right was tied to a property qualification: one had to own or lease land and pay taxes, or be closely related to somebody who did, to be eligible to vote.[66][88] 300,000 of 700,000 previously eligible nobles were thus disfranchised, much to their displeasure.[65] Voting rights were restored to landowners who were in military service. They had lost these rights in 1775.[65] Voting was limited to males of at least 18 years of age.[81] The eligible voters elected deputies to local powiats, or county sejmiks, which elected deputies to the General Sejm.[81]

Finally, Article VI explicitly abolished several institutional sources of government weakness and national anarchy, including the liberum veto (which was replaced by a simple majority vote), confederations and confederated sejms, and the excessive influence of sejmiks stemming from the previously binding nature of their instructions to their Sejm deputies.[33][66] The confederations were declared "contrary to the spirit of this constitution, subversive of government and destructive of society".[89] Thus the new constitution strengthened the powers of the Sejm, moving the country towards a constitutional monarchy.[33][66]

Executive power, according to Article V and Article VII, was in the hands of "the king in his council", a cabinet of ministers called the Guardians of the Laws (or Guard of the Laws, Straż Praw).[89] The ministries could not create or interpret the laws and all acts of the foreign ministry were provisional and subject to the Sejm's approval.[89] The king presided over this council, which was composed of the Roman Catholic Primate of Poland—who was also president of the Education Commission—and five ministers appointed by the king: a minister of police, a minister of the seal (internal affairs), a minister of foreign affairs, a minister belli (of war), and a minister of treasury.[81] Council members also included—without a vote—the Crown Prince, the Marshal of the Sejm, and two secretaries.[89] This royal council descended from similar councils that had functioned since King Henry's Articles (1573), and from the recent Permanent Council. Acts of the king required the countersignature of the respective minister.[90] A minister was required to cosign a law if the king demanded it, unless that minister refused and all other ministers unanimously endorsed his objection, in which case the king could withdraw the law or press the issue by taking it before the parliament.[82] The stipulation that the king, "doing nothing of himself, ... shall be answerable for nothing to the nation," parallels the British constitutional principle that "The king can do no wrong." (In both countries, the respective minister was responsible for the king's acts.)[90][91] The ministers were responsible to the Sejm, which could dismiss them by a vote of no confidence with a two-third majority in both houses.[33][66][81] Ministers could be also held accountable by the Sejm court, and a simple majority vote was sufficient for the Sejm to demand that a minister face an impeachment trial.[33][90] The king was the nation's commander-in-chief, commanding its armies; the institution of the hetman (high-ranking military official) was not mentioned.[90] The king also had the right to grant pardon except in cases of treason.[82] The decisions of the royal council were carried out by commissions, including the previously created Commission of National Education, and the new Commissions for Police, the Military and the Treasury, whose members were elected by the Sejm.[90]

of Poland |

|---|

The constitution also changed the government from an elective monarchy in its unique Polish variant to a hereditary monarchy.[33][66][93] This provision was intended to reduce the destructive, vying influences of foreign powers at each royal election.[94][lower-alpha 4] The royal dynasty was elective, and if it were to die out a new one would be chosen by "the Nation".[89] The king held the throne "by the grace of God and the will of the Nation", and "all authority derives from the will of the Nation."[33][81] The institution of pacta conventa was preserved.[90] On Stanisław August's death the Polish throne would become hereditary and pass to Frederick Augustus I of Saxony of the House of Wettin, which had provided Poland's two most recent elective kings before Stanisław August.[66][90] This provision was contingent upon Frederic Augustus' consent, but he declined when the offer was presented to him by Adam Czartoryski.[66][lower-alpha 5]

Discussed in Article VIII, the judiciary was separated from the two other branches of the government,[81][90] and was to be served by elective judges.[81] Courts of first instance existed in each voivodeship and were in constant session,[81] with judges elected by the regional sejmik assemblies.[82] Appellate tribunals were established for the provinces, based on the reformed Crown Tribunal and Lithuanian Tribunal.[81] The Sejm elected from its deputies the judges for the Sejm court, a precursor to the modern State Tribunal of Poland.[81][90] Referendary courts were established in each province to hear the cases of the peasantry.[90] Municipal courts, described in the law on towns, complemented this system.[90]

Article IX covered procedures for regency, which should be taken up jointly by the council of the Guardians, headed by the Queen, or in her absence by the Primate.[82][98] Article X stressed the importance of education of royal children and tasked the Commission of National Education with this responsibility.[98] The last article of the constitution, Article XI, concerned the national standing army.[82] Said army was defined as a "defensive force" dedicated "solely to the nation's defense".[82] The army was to be increased in strength to 100,000 men.[99]

To further enhance the Commonwealth's integration and security, the constitution abolished the erstwhile union of Poland and Lithuania in favor of a unitary state.[49][100] Its full establishment, supported by Stanisław August and Kołlątaj, was opposed by many Lithuanian deputies.[100] As a compromise, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania received numerous privileges guaranteeing its continued existence.[100] Related acts included the Deklaracja Stanów Zgromadzonych (Declaration of the Assembled Estates) of May 5, 1791, confirming the Government Act adopted two days earlier, and the Zaręczenie Wzajemne Obojga Narodów (Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations, i.e., of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) of October 22, 1791, affirming the unity and indivisibility of Poland and the Grand Duchy within a single state and their equal representation in state-governing bodies.[76][101] The Reciprocal Guarantee strengthened the Polish–Lithuanian union while keeping many federal aspects of the state intact.[100][102][103]

The Constitution of the 3rd May was also translated into Lithuanian, that marked the significant change in the upper society way of thinking, marked the efforts of the modernization of the State.[104][105][106]

The Constitution remained to the last a work in progress. The provisions of the Government Act were detailed in a number of laws passed in May and June 1791: on sejm courts (two acts of May 13), the Guardians of the Laws (June 1), the national police commission (a ministry, June 17) and municipal administration (June 24). The constitution included provisions for amendments, which were to be dealt with by an extraordinary Sejm held every 25 years.[66][86] Its co-author Hugo Kołłątaj announced that work was underway on "an economic constitution ... guaranteeing all rights of property [and] securing protection and honor to all manner of labor ...".[107] A third planned basic law was mentioned by Kołłątaj; a "moral constitution", most likely a Polish analog to the United States Bill of Rights and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.[107] The constitution called for the preparation of a new civil and criminal code, tentatively called the Stanisław August Code.[98][108] The King also planned a reform improving the situation of the Jews.[108]

Aftermath: war and the final two partitions

The constitution remained in effect for little over a year before being overthrown by Russian armies allied with conservative Polish nobility in the Polish–Russian War of 1792, also known as the War in Defense of the Constitution.[70] With the wars between Turkey and Russia and Sweden and Russia having ended, Empress Catherine was furious over the adoption of the document, which she believed threatened Russian influence in Poland.[61][62][109] Russia had viewed Poland as a de facto protectorate.[110] "The worst possible news have arrived from Warsaw: the Polish king has become almost sovereign" was the reaction of one of Russia's chief foreign policy authors, Alexander Bezborodko, when he learned of the new constitution.[111] The contacts of Polish reformers with the Revolutionary French National Assembly were seen by Poland's neighbors as evidence of a revolutionary conspiracy and a threat to the absolute monarchies.[112][113] The Prussian statesman Ewald von Hertzberg expressed the fears of European conservatives: "The Poles have given the coup de grâce to the Prussian monarchy by voting a constitution", elaborating that a strong Commonwealth would likely demand the return of the lands Prussia acquired in the First Partition.[111][114]

Magnates who had opposed the constitution draft from the start, Franciszek Ksawery Branicki, Stanisław Szczęsny Potocki, Seweryn Rzewuski, and Szymon and Józef Kossakowski, asked Tsarina Catherine to intervene and restore their privileges—the Cardinal Laws abolished under the new statute.[70] To that end these magnates formed the Targowica Confederation.[70] The Confederation's proclamation, prepared in St. Petersburg in January 1792, criticized the constitution for contributing to "contagion of democratic ideas" following "the fatal examples set in Paris".[115][116] It asserted that "The parliament ... has broken all fundamental laws, swept away all liberties of the gentry and on the third of May 1791 turned into a revolution and a conspiracy."[117] The Confederates declared an intention to overcome this revolution. We "can do nothing but turn trustingly to Tsarina Catherine, a distinguished and fair empress, our neighboring friend and ally", who "respects the nation's need for well-being and always offers it a helping hand", they wrote.[117]

Russian armies entered Poland and Lithuania, starting the Polish–Russian War of 1792.[70] The Sejm voted to increase the army of the Commonwealth to 100,000 men, but owing to insufficient time and funds this number was never achieved and soon abandoned even as a goal.[70][118] The Polish King and the reformers could field only a 37,000-man army, many of them untested recruits.[119] This army, under the command of Józef Poniatowski and Tadeusz Kościuszko, defeated or fought to a draw the Russians on several occasions, but in the end, a defeat loomed inevitable.[70] Despite Polish requests, Prussia refused to honor its alliance obligations.[120] Stanisław August's attempts at negotiations with Russia proved futile.[121] As the front lines kept shifting to the west and in July 1792 Warsaw was threatened with siege by the Russians, the King came to believe that victory was impossible against the numerically superior enemy, and that surrender was the only alternative to total defeat.[121] Having received assurances from the Russian ambassador Yakov Bulgakov that no territorial changes will occur, the Guardians of the Laws cabinet voted 8:4 to surrender.[121] On July 24, 1792, King Stanisław August Poniatowski joined the Targowica Confederation, as the Empress had demanded.[70] The Polish Army disintegrated.

Many reform leaders, believing their cause was for now lost, went into self-imposed exile. Some hoped that Stanisław August would be able to negotiate an acceptable compromise with the Russians, as he had done in the past.[121] But the King had not saved the Commonwealth and neither had the Targowica Confederates, who governed the country for a short while. To their surprise, the Grodno Sejm, bribed or intimidated by the Russian troops, enacted the Second Partition of Poland.[70][70][116][122] On November 23, 1793, it concluded its deliberations under duress, annulling the constitution and acceding to the Second Partition.[123][124] Russia took 250,000 square kilometres (97,000 sq mi), while Prussia took 58,000 square kilometres (22,000 sq mi).[122] The Commonwealth now comprised no more than 215,000 square kilometres (83,000 sq mi).[125] What was left of the Commonwealth was merely a small buffer state with a puppet king, and Russian garrisons keeping an eye on the reduced Polish army.[125][126]

For a year and a half, Polish patriots waited while planning an insurrection.[122] On March 24, 1794 in Kraków, Tadeusz Kościuszko declared what has come to be known as the Kościuszko Uprising.[122] On May 7, he issued the Proclamation of Połaniec (Uniwersał Połaniecki), granting freedom to the peasants and ownership of land to all who fought in the insurrection. Revolutionary tribunals administered summary justice to those deemed traitors to the Commonwealth.[122] After initial victories at the Battle of Racławice (April 4), the capture of Warsaw (April 18) and the Wilno (April 22)—the Uprising was crushed when the forces of Russia, Austria and Prussia joined in a military intervention.[127] Historians consider the Uprising's defeat to have been a foregone conclusion in face of the superiority in numbers and resources of the three invading powers. The defeat of Kościuszko's forces led in 1795 to the third and final partition of the Commonwealth.[127]

Legacy

Historical significance

The constitution has been both idealized and criticized for either not going far enough or for being too radical.[75] As it remained in force for only 18 months and 3 weeks, its influence was in any case limited.[127] For generations, the memory of the constitution—recognized by political scientists as a progressive document for its time—helped keep alive Polish aspirations for an independent and just society, and continued to inform the efforts of its authors' descendants.[7][33] Bronisław Dembiński, a Polish constitutional scholar, stated a century later that, "The miracle of the Constitution did not save the state but did save the nation."[7] In Poland it is mythologized, and viewed as a national symbol and the culmination of enlightenment in Polish history and culture.[33][46] In the words of two of its co-authors, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj, it was "the last will and testament of the expiring Country."[lower-alpha 1][1] The May 3 anniversary of its adoption has been observed as Poland's most important civil holiday since Poland regained independence in 1918.[128]

The constitution was a milestone in the history of law and the rise of democracy.[5][129] Irish statesman Edmund Burke described it as "the noblest benefit received by any nation at any time ... Stanislas II has earned a place among the greatest kings and statesmen in history."[74][94] It was the first to follow the 1788 ratification of the United States Constitution.[129][130] Poland and the United States, though geographically distant, displayed similarities in their approaches to the design of political systems.[129] The May 3 Constitution has been called the second constitution in world history.[4][59] American expert on constitutional law Albert Blaustein called it the "world's second national constitution",[2] and American journalist Bill Moyers wrote that it was "Europe's first codified national constitution (and the second oldest in the world)".[3] British historian Norman Davies calls it "the first constitution of its type in Europe".[5][lower-alpha 2] Together with the Great Sejm, it has been subject to a large body of works by Polish scholars, starting with the still-often cited 19th-century works of Walerian Kalinka and Władysław Smoleński, and continued in the 20th century by Bogusław Leśnodorski.[46]

The document's official name was Ustawa Rządowa ("Government Act"), where "government" referred to the political system.[59] In the Commonwealth, the term "constitution" (Polish: konstytucja) had denoted all the legislation, of whatever character, that had been passed by a Sejm.[131]

Holiday

May 3 was declared a Polish holiday (Constitution Day—Święto Konstytucji 3 Maja) on May 5, 1791.[132] The holiday was banned during the partitions of Poland but reinstated in April 1919 under the Second Polish Republic—the first holiday officially introduced in the newly independent country.[128][132][133] It was again outlawed during World War II by both the Nazi and Soviet occupiers. It was celebrated in Polish cities in May 1945, although in a mostly spontaneous manner.[128] The 1946 anti-communist demonstrations did not endear it to the Polish communists, and it competed for attention with the communist-endorsed May 1 Labor Day celebrations in the Polish People's Republic; this led to its "rebranding" as Democratic Party Day and removal from the list of national holidays by 1951.[128][132] Until 1989, May 3 was a frequent occasion for anti-government and anti-communist protests.[128] May 3 was restored as an official Polish holiday in April 1990 after the fall of communism.[132] In 2007, May 3 was declared a Lithuanian national holiday.[134] Polish-American pride has been celebrated on the same date, for instance in Chicago, where since 1982 Poles have marked it with festivities and the annual Polish Constitution Day Parade.[135]

Notes

- 1 2 Machnikowski uses the word Fatherland.[1] The English translation of the Constitution of May 3, 1791, by Christopher Kasparek, reproduced in Wikisource, renders "ojczyzna" as "country" (the usual English-language equivalent), e.g. at the end of section II, "The Landed Nobility". The English translation of the Polish "ojczyzna" is "fatherland" – both words are calques of the Latin "patria," itself derived from "pater" ("father").

- 1 2 The claims of "first" and "second constitution" have been disputed, particularly as different scholars define the word constitution differently. Both the U.S. and Polish constitutions were preceded by earlier ones, including some also termed constitutions, for example, the Corsican Constitution of 1755.[6] See history of the constitution.

- ↑ The contemporaneous United States Constitution sanctioned the continuation of slavery. Thus neither of the two constitutions enfranchised all its adult male population: the U.S. Constitution excluded the slaves; the Polish Constitution – the peasants.[82]

- ↑ Stanisław August had been elected as king in 1764 thanks to the significant support of his ex-mistress, Russian Tsarina Catherine the Great.[95] The Russians spent about 2.5 million rubles to support his election, Poniatowski's supporters and opponents engaged in some military posturing and even minor clashes, and in the end, the Russian army was deployed only a few miles from the election sejm, which met at Wola near Warsaw.[96][97]

- ↑ In 1807, Napoleon persuaded Frederic Augustus to become the king of the Duchy of Warsaw established by the French Emperor on lands of the former Commonwealth.[49]

References

- 1 2 Piotr Machnikowski (December 1, 2010). Contract Law in Poland. Kluwer Law International. p. 20. ISBN 978-90-411-3396-0. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- 1 2 Albert P. Blaustein (1993). Constitutions of the world. Wm. S. Hein Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8377-0362-6.

- 1 2 Bill Moyers (May 5, 2009). Moyers on Democracy. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-307-38773-8. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- 1 2 Sandra Lapointe; Jan Wolenski; Mathieu Marion (2009). The Golden Age of Polish Philosophy: Kazimierz Twardowski's Philosophical Legacy. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 978-90-481-2400-8. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Norman Davies (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 699. ISBN 0-19-820171-0.

- ↑ Dorothy Carrington (July 1973). "The Corsican constitution of Pasquale Paoli (1755–1769)". The English Historical Review. 88 (348): 481. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxxviii.cccxlviii.481. JSTOR 564654.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Brzezinski, Mark F. (1991). "Constitutional Heritage and Renewal: The Case of Poland". Virginia Law Review. 77 (1): 49–112. JSTOR 1073115.

- ↑ Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Piotr Stefan Wandycz (2001). The price of freedom: a history of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the present. Psychology Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-415-25491-5. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Norman Davies (March 30, 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Daniel Stone (September 1, 2001). The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386–1795. University of Washington Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Daniel Stone (September 1, 2001). The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386–1795. University of Washington Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ J. K. Fedorowicz; Maria Bogucka; Henryk Samsonowicz (1982). A Republic of nobles: studies in Polish history to 1864. Cambridge University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-521-24093-2. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Rogalewski, Tadeusz (2001). Lumen Marianorum: Stanislaus Papczynski (1631–1701) (PDF). (Paul and Ewa St. Jean (trans. and ed.)). Stockbridge, MA: Marian Press. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1505–1764 [History of Poland, 1505–1764] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 251. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- 1 2 Francis Ludwig Carsten (January 1, 1961). The new Cambridge modern history: The ascendancy of France, 1648–88. Cambridge University Press. pp. 561–562. ISBN 978-0-521-04544-5.

- 1 2 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Tanisha M. Fazal (October 27, 2011). State Death: The Politics and Geography of Conquest, Occupation, and Annexation. Princeton University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-4008-4144-8. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ↑ Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1764–1864 [History of Poland, 1764–1864] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 63, 72. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ↑ Norman Davies (March 30, 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 153–154. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Piotr Stefan Wandycz (2001). The price of freedom: a history of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the present. Psychology Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-415-25491-5. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 Norman Davies (January 20, 1998). Europe: a history. HarperCollins. p. 659. ISBN 978-0-06-097468-8. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1764–1864 [History of Poland, 1764–1864] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 60–63. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1764–1864 [History of Poland, 1764–1864] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 62–63, 72–73. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- 1 2 3 John P. LeDonne (1997). The Russian empire and the world, 1700–1917: the geopolitics of expansion and containment. Oxford University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-19-510927-6. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Krzysztof Bauer (1991). Uchwalenie i obrona Konstytucji 3 Maja [Passing and defense of the Constitution of May 3] (in Polish). Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne. p. 9. ISBN 978-83-02-04615-5.

- ↑ Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1764–1864 [History of Poland, 1764–1864] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 64. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Hugh Seton-Watson (February 1, 1988). The Russian empire, 1801–1917. Clarendon Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-19-822152-4. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richard Butterwick (1998). Poland's last king and English culture: Stanisław August Poniatowski, 1732–1798. Clarendon Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-19-820701-6. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 George Sanford (2002). Democratic government in Poland: constitutional politics since 1989. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-333-77475-5. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1764–1864 [History of Poland, 1764–1864] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 65. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Andrzej Jezierski; Cecylia Leszczyńska (2003). Historia gospodarcza Polski [Economic History of Poland] (in Polish). Key Text Wydawnictwo. p. 68. ISBN 978-83-87251-71-0. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ David R. Collins; Larry Nolte (September 1995). Casimir Pulaski: soldier on horseback. Pelican Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-56554-082-8. Retrieved August 24, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jerzy Lukowski; Hubert Zawadzki (2001). A concise history of Poland. Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–99. ISBN 978-0-521-55917-1. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Sharon Korman (1996). The right of conquest: the acquisition of territory by force in international law and practice. Oxford University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-19-828007-1. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ David Lay Williams (August 1, 2007). Rousseau's Platonic Enlightenment. Penn State Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-271-02997-9. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ↑ Matthew P. Romaniello; Charles Lipp (March 1, 2011). Contested spaces of nobility in early modern Europe. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-4094-0551-1. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ↑ Jerzy Lukowski (August 3, 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- 1 2 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Lukowski, Jerzy (February 11, 2009). "Recasting Utopia: Montesquieu, Rousseau and the Polish constitution of 3 May 1791". The Historical Journal. 37 (01): 65. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00014709.

- ↑ Maurice William Cranston (1997). The solitary self: Jean-Jacques Rousseau in exile and adversity. University of Chicago Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-226-11865-9. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 169–171. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Daniel Stone (September 1, 2001). The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386–1795. University of Washington Press. pp. 274–275. ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ↑ Ted Tapper; David Palfreyman (December 23, 2004). Understanding mass higher education: comparative perspectives on access. RoutledgeFalmer. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-415-35491-2. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Norman Davies (May 2005). God's Playground: 1795 to the present. Columbia University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-231-12819-3. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- 1 2 Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1764–1864 [History of Poland, 1764–1864] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 73. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- 1 2 Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1764–1864 [History of Poland, 1764–1864] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ↑ Richard Butterwick (1998). Poland's last king and English culture: Stanisław August Poniatowski, 1732–1798. Clarendon Press. pp. 158–162. ISBN 978-0-19-820701-6.

- ↑ Janusz Justyński (1991). The Origin of human rights: the constitution of 3 May 1791, the French declaration of rights, the Bill of Rights : proceedings at the seminar held at the Nicolaus Copernicus University, May 3–5, 1991. Wydawn. Adam Marszałek. p. 171. ISBN 978-83-85263-24-1. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ↑ Antoni Jan Ostrowski (1873). Żywot Tomasza Ostrowskiego, ministra rzeczypospolitej póżniej,prezesa senatu xięstwa warszawskiego i królestwa polskiego: obejmujacy rys wypadḱow krajowych od 1765 roku do 1817 [The Life of Tomasz Ostrowski ...] (in Polish). Nakł. K. Ostrowskiego. p. 73. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Juliusz Bardach; Bogusław Leśnodorski; Michał Pietrzak (1993). Historia ustroju i prawa polskiego [History of the Polish State and Law] (in Polish). PWN. pp. 304–305. ISBN 978-83-01-11026-0.

- 1 2 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 Robert Bideleux; Ian Jeffries (January 28, 1998). A history of eastern Europe: crisis and change. Psychology Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-415-16111-4.

- 1 2 3 Jerzy Lukowski (August 3, 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ↑ Piotr Stefan Wandycz (2001). The price of freedom: a history of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the present. Psychology Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-415-25491-5. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- 1 2 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Marceli Handelsman (1907). Konstytucja trzeciego Maja r. 1791 [Constitution of May 3] (in Polish). Druk. Narodowa. pp. 50–52. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1764–1864 [History of Poland, 1764–1864] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 83–86. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ↑ Poland; Jerzy Kowecki (1991). Konstytucja 3 Maja 1791 [Constitution of May 3] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 51.

- ↑ Stanisław Grodziski (1999). Polska w czasach przełomu: (1764–1815) [Poland at the Turning point (1764–1815)] (in Polish). Fogra. p. 129. ISBN 978-83-85719-45-8. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Joseph Kasparek-Obst (June 1, 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-881284-09-3.

- 1 2 3 Juliusz Bardach; Bogusław Leśnodorski; Michał Pietrzak (1993). Historia ustroju i prawa polskiego [History of the Polish State and Law] (in Polish). PWN. p. 318. ISBN 978-83-01-11026-0.

- 1 2 Joseph Kasparek-Obst (June 1, 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-881284-09-3.

- 1 2 Hillar, Marian (1992). "The Polish Constitution of May 3, 1791: Myth and Reality". The Polish Review. 37 (2): 185–207. JSTOR 25778627.

- 1 2 3 4 Jerzy Lukowski (August 3, 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ↑ Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1764–1864 [History of Poland, 1764–1864] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 83. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- 1 2 J. K. Fedorowicz; Maria Bogucka; Henryk Samsonowicz (1982). A Republic of nobles: studies in Polish history to 1864. Cambridge University Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-521-24093-2. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Wagner, W. J. (1991). "May 3, 1791, and the Polish constitutional tradition". The Polish Review. 36 (4): 383–395. JSTOR 25778591.

- ↑ Stanisław Grodziski (1999). Polska w czasach przełomu: (1764–1815) [Poland at the Turning point (1764–1815)] (in Polish). Fogra. p. 157. ISBN 978-83-85719-45-8. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ↑ Stanisław Grodziski (1999). Polska w czasach przełomu: (1764–1815) [Poland at the Turning point (1764–1815)] (in Polish). Fogra. p. 114. ISBN 978-83-85719-45-8. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ↑ Joseph Kasparek-Obst (June 1, 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-881284-09-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Jerzy Lukowski (August 3, 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ↑ Joseph Kasparek-Obst (June 1, 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-881284-09-3.

- ↑ Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jerzy Lukowski (August 3, 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Jerzy Lukowski (August 3, 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ↑ Joseph Kasparek-Obst (June 1, 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. pp. 45–49. ISBN 978-1-881284-09-3.

- ↑ Old Lithuanian texts

- ↑ Joseph Kasparek-Obst (June 1, 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-881284-09-3.

- 1 2 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Jerzy Michalski (2011). "Stanisław August Poniatowski". Polski Słownik Biograficzny (in Polish). 41. Drukarnia Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. p. 616.

- ↑ Norman Davies (March 30, 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Bartłomiej Szyndler (January 2009). RacŁawice 1794. Bellona. p. 64. ISBN 978-83-11-11606-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Jerzy Lukowski (August 3, 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ↑ Jeremy Black (2004). Kings, nobles and commoners: states and societies in early modern Europe, a revisionist history. I.B.Tauris. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-86064-986-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Juliusz Bardach; Bogusław Leśnodorski; Michał Pietrzak (1993). Historia ustroju i prawa polskiego [History of the Polish State and Law] (in Polish). PWN. p. 309. ISBN 978-83-01-11026-0.

- ↑ Poland; Jerzy Kowecki (1991). Konstytucja 3 Maja 1791 [Constitution of May 3] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 105–107. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ Maria Konopka-Wichrowska (August 13, 2003). "My, Litwa" [We, Lithuania] (in Polish). Podkowiański Magazyn Kulturalny. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

Ostatnim było Zaręczenie Wzajemne Obojga Narodów przy Konstytucji 3 Maja, stanowiące część nowych paktów konwentów – zdaniem historyka prawa Bogusława Leśnodorskiego: "zacieśniające unię, ale utrzymujące nadal federacyjny charakter Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów" [The last was the Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations at Constitution of 3 May, forming a part of the new pacta conventa – according to the law historian Bogusław Leśnodorski "tightening the union, but retaining the federal character of the Commonwealth of Both Nations".

- ↑ Bardach, Juliusz (1992). "The Constitution of May Third and the mutual assurance of the Two Nations". The Polish Review. 36 (4): 407–420. JSTOR 25778593.

- ↑ Tumelis, Juozas (1978). "Gegužės Trečiosios konstitucijos ir Ketverių metų seimo nutarimų lietuviškas vertimas". Lietuvos istorijos metraštis (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas: 95–105. ISSN 0202-3342. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ↑ Old Lithuanian texts

- ↑ Tomas Baranauskas: Ką Lietuvai reiškė Gegužės 3-osios Konstitucija? "Vienalaikis Konstitucijos vertimas į lietuvių kalbą yra reikšmingas mūsų istorijos faktas – Gegužės 3-osios Konstitucija buvo pirmasis valstybės įstatymas, netrukus po jos priėmimo išverstas į lietuvių kalbą. Nuo čia prasideda lietuvių kalbos kelias į valstybės kanceliariją. Lietuviškai atsišaukimus jau leido Kosciuškos sukilimo vyriausybė, tad lietuvių kalbos vartojimo poreikis tarp Konstitucijos šalininkų buvo akivaizdus." "At the same time, the Constitution was translated into Lithuanian language. The Constitution was the first state law, issued in Lithuanian language. Since then, the journey of Lithuanian language into the State Chancellery began: documents of Kosciuszko uprising [in Vilnius and elsewhere] were issued in Lithuanian and the need of using Lithuanian language among the proponents of the Constitution was obvious".

- 1 2 Joseph Kasparek-Obst (June 1, 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-1-881284-09-3.

- 1 2 Jerzy Michalski (2011). "Stanisław August Poniatowski". Polski Słownik Biograficzny (in Polish). 41. Drukarnia Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. p. 627.

- ↑ Paul W. Schroeder (1996). The transformation of European politics, 1763–1848. Oxford University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-19-820654-5. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Jerzy Lukowski; Hubert Zawadzki (2001). A concise history of Poland. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-521-55917-1. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- 1 2 Krzysztof Bauer (1991). Uchwalenie i obrona Konstytucji 3 Maja [Passing and Fall of the May 3 Constitution] (in Polish). Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne. p. 167. ISBN 978-83-02-04615-5.

- ↑ Francis W. Carter (1994). Trade and urban development in Poland: an economic geography of Cracow, from its origins to 1795. Cambridge University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-521-41239-1.

- ↑ Norman Davies (March 30, 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ↑ Carl L. Bucki (May 3, 1996). "Constitution Day: May 3, 1791". Polish Academic Information Center. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ↑ Robert Howard Lord (1915). The second partition of Poland: a study in diplomatic history. Harvard University Press. p. 275. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- 1 2 Michal Kopeček (2006). Discourses of collective identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945): texts and commentaries. Central European University Press. pp. 282–284. ISBN 978-963-7326-52-3. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- 1 2 Michal Kopeček (2006). Discourses of collective identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945): texts and commentaries. Central European University Press. pp. 284–285. ISBN 978-963-7326-52-3. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- ↑ Józef Andrzej Gierowski (1986). Historia Polski, 1764–1864 [History of Poland, 1764–1864] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 78–82. ISBN 978-83-01-03732-1. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ↑ Juliusz Bardach; Bogusław Leśnodorski; Michał Pietrzak (1993). Historia ustroju i prawa polskiego [History of the Polish State and Law] (in Polish). PWN. p. 317. ISBN 978-83-01-11026-0.

- ↑ Jerzy Łojek (1986). Geneza i obalenie Konstytucji 3 maja [Genesis and Fall of the Constitution of 3 May] (in Polish). Wydawn. Lubelskie. pp. 325–326. ISBN 978-83-222-0313-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Jerzy Michalski (2011). "Stanisław August Poniatowski". Polski Słownik Biograficzny (in Polish). 41. Drukarnia Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. p. 628.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 186–187. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4.

- ↑ Norman Davies (March 30, 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ David Pickus (2001). Dying With an Enlightening Fall: Poland in the Eyes of German Intellectuals, 1764–1800. Lexington Books. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7391-0153-7.

- 1 2 Richard C. Frucht (2005). Eastern Europe: an introduction to the people, lands, and culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ↑ Lynne Olson; Stanley Cloud (September 16, 2003). A question of honor: the Kościuszko Squadron : the forgotten heroes of World War II. Knopf. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-375-41197-7. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rafał Kowalczyk; Łukasz Kamiński (May 3, 2008). "Zakazane święta PRLu" [Forbidden holidays of PRL] (in Polish). Polskie Radio Online. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 John Markoff (1996). Waves of democracy: social movements and political change. Pine Forge Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8039-9019-7. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

The first European country to follow the U.S. example was Poland in 1791.

- ↑ Isaac Kramnick (1987). "Introduction". In James Madison; Alexander Hamilton; John Jay. The Federalist papers. Penguin. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-14-044495-7. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ↑ Jerzy Kowalski (2009). Konstytucja Federacji Rosyjskiej a Rosyjska i Europejska tradycja konstytucyjna [Constitution of the Russian Federation and Russian and European Constitutional Tradition] (in Polish). PWP Iuris. p. 136. ISBN 978-83-89363-69-5. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Konstytucja 3 Maja – rys historyczny" [Constitution of May 3 – Historical Overview] (PDF) (in Polish). City of Warsaw. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ↑ Iwona Pogorzelska (2002). "Prezentacja na podstawie artykułu Romany Guldon "Pamiątki Konstytucji 3 Maja przechowywane w zasobie Archiwum Państwowego w Kielcach."" [Presentation on the basis of Romana Guldon's article "Relics of Constitution of May 3 kept in the collections of National Archives in Kielce] (in Polish). Almanach Historyczny, T. 4, Kielce. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Rok 2007: Przegląd wydarzeń" [Year 2007: Overview of Events] (in Polish). Tygnodnik Wileńszczyzny. February 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Thousands Attend Polish Constitution Day Parade". CBS. May 7, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

Further reading

- Blackburn, Edwin C. (1991). "Stanislaus Leszczynski and the Polish Constitution of May 3, 1791". The Polish Review. 36 (4): 397–405. JSTOR 25778592.

- Butterwick, Richard (2005). "Political Discourses of the Polish Revolution, 1788–92". The English Historical Review. 120 (487): 695–731. doi:10.1093/ehr/cei126. JSTOR 3489412.

- Duzinkiewicz, Janusz. Fateful Transformations: The Four Years' Parliament and the Constitution of May 3, 1791. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-88033-265-4.

- Fiszman, Samuel (1997). Constitution and Reform in Eighteenth-Century Poland: The Constitution of 3 May 1791. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33317-2.

- Fried, Daniel (2009). "Poland, America, and the Arc of History". The Polish Review. 54 (2): 141–146. JSTOR 25779807.

- Gierowski, Józef Andrzej (1996). The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the XVIIIth Century: From Anarchy to Well-Organised State. Translated from Polish by Henry Leeming. Krakow: Polish Academy of Sciences. ISBN 83-86956-15-1.

- Hoskins, Janina W. (1976). "'A Lesson Which All Our Countrymen Should Study': Jefferson Views Poland". The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress. 33 (1): 29–46. JSTOR 29781662.

- Kadziela, Łukasz; Strybel, Robert (1994). "The 1794 Kościuszko Insurrection". The Polish Review. 39 (4): 387–392. JSTOR 27920649.

- Lukowski, Jerzy (1999). The Partitions of Poland: 1772, 1793, 1795. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-29274-3.

- Lukowski, Jerzy (2004). "Political Ideas among the Polish Nobility in the Eighteenth Century (To 1788)". The Slavonic and East European Review. 82 (1): 1–26. JSTOR 4213847.

- Murphy, Curtis G. (2012). "Burghers versus Bureaucrats: Enlightened Centralism, the Royal Towns, and the Case of the Propinacja Law in Poland-Lithuania, 1776–1793". Slavic Review. 71 (2): 385–409. doi:10.5612/slavicreview.71.2.0385. JSTOR 10.5612/slavicreview.71.2.0385.

- Polska (1985). Ustawodawstwo Sejmu Wielkiego z 1791 r [Legislation of the Great Sejm of 1791] (in Polish). Polska Akad. Nauk, Bibl. Kórnicka. Retrieved June 18, 2012. – compilation of facsimile reprints of 1791 legislation pertinent to the Constitution of May 3, 1791.

- Emanuel Rostworowski (1985). Maj 1791-maj 1792—rok monarchii konstytucyjnej [May 1791 – May 1792: the Year of Constitutional Monarchy] (in Polish). Zamek Królewski w Warszawie. ISBN 978-83-00-00961-9. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- Stone, Daniel (1981). "Daniel Hailes and the Polish Constitution of May 3, 1791". The Polish Review. 26 (2): 51–63. JSTOR 25777821.

- Stone, Daniel (1993). "The First (and Only) Year of the May 3 Constitution". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 35 (1/2): 69–86. JSTOR 40869459.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Constitution of May 3, 1791 |

- Photos of original document

- Polishconstitution.org — about the May 3 1791 Constitution, includes a partial English translation by Christopher Kasparek.

- Collection of digitized versions of the May 3 1791 Constitution and various related documents in the Digital National Library Polona.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Constitution of the 3rd May 1791. |