A Game at Chess

| A Game at Chess | |

|---|---|

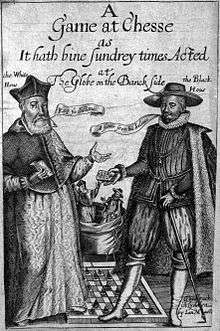

Title page of the first printed edition. It depicts the Fat Bishop saying "Keep your distance", and the Black Knight tempting him with "A letter from his holiness". The characters' faces are caricatures of de Dominis and Gondomar. | |

| Written by | Thomas Middleton |

| Date premiered | August 1624 |

| Place premiered | Globe Theatre, London |

| Original language | English |

| Subject | Anglo-Spanish relations, Protestantism and Catholicism |

| Genre | Satire, allegory |

| Setting | A chessboard |

A Game at Chess is a comic satirical play by Thomas Middleton, first staged in August 1624 by the King's Men at the Globe Theatre, notable for its political content.

The play

The drama seems to be about a chess match, and even contains a genuine chess opening: the Queen's Gambit Declined. Instead of personal names, the characters are known as the White Knight, the Black King, etc. However, audiences immediately recognized the play as an allegory for the stormy relationship between Spain (the black pieces) and Great Britain (the white pieces). King James I of England is the White King; King Philip IV of Spain is the Black King. In particular, the play dramatizes the struggle of negotiations over the proposed marriage of the then Prince Charles with the Spanish princess, the Infanta Maria. It focuses on the journey by Prince Charles (the "White Knight") and George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (the "White Duke", or rook) to Madrid in 1623.

Among the secondary targets of the satire was the former Archbishop of Split, Marco Antonio de Dominis, who was caricatured as the Fat Bishop (played by William Rowley). De Dominis was a famous turncoat of his day: he had left the Roman Catholic Church to join the Anglican Church—and then returned to Rome again. The traitorous White King's Pawn is a composite of several figures, including Lionel Cranfield, 1st Earl of Middlesex, a former Lord Treasurer who was impeached before the House of Lords in April 1624.

The former Spanish ambassador to London, Diego Sarmiento de Acuña, conde de Gondomar, was blatantly satirized and caricatured in the play as the Machiavellian Black Knight. (The King's Men went so far as to buy discarded items of Gondomar's wardrobe for the role.)[1] His successor recognized the satire and complained to King James. His description of the crowd's reaction to the play yields a vivid picture of the scene:

- There was such merriment, hubbub and applause that even if I had been many leagues away it would not have been possible for me not to have taken notice of it.[2]

The play was stopped after nine performances (6–16 August, Sundays omitted), but not before it had become "the greatest box-office hit of early modern London".[3] The Privy Council opened a prosecution against the actors and the author of the play on 18 August (it was then illegal to portray any modern Christian king on the stage). The Globe Theatre was shut down by the prosecution, though Middleton was able to acquit himself by showing that the play had been passed by the Master of the Revels, Sir Henry Herbert. Nevertheless, further performance of the play was forbidden and Middleton and the actors were reprimanded and fined. Middleton never wrote another play.

An obvious question arises: if the play was clearly offensive, why did the Master of the Revels license it on 12 June that summer? Herbert may have been acting in collusion with the "war party" of the day, which included figures as prominent as Prince Charles and the Duke of Buckingham; they were eager for a war with Spain and happy to see public ire roused against the Spanish. If this is true, Middleton and the King's Men were themselves pawns in a geopolitical game of chess.

Characters

The characters are based on real political figures. The identifications below are suggested by Gary Taylor in Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works (OUP, 2007), pp. 1830–1.

Opening sequence

- Prologue

- Ignatius Loyola, ghost of the founder of the Jesuits

- Error, an allegorical personification of religious heresy

White House

- White King. Based on King James I of England.

- White King's Pawn. A spy for the Black House, most often identified as based on Lionel Cranfield, earl of Middlesex.

- White Queen. Based on Elizabeth of Bohemia, daughter of King James

- White Queen's Pawn. A young virgin, former fiancee of the White Bishop's Pawn.

- White Knight. Based on Prince Charles, son of King James

- White Duke. Based on George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, favourite of King James and friend of Charles

- Fat Bishop. Based on Marc Antonio de Dominis, Bishop of Spalato. A former bishop of the Black House who has recanted to join the White House. A comic role, written for the actor William Rowley.

- Fat Bishop's Pawn. A servant.

- White Bishop. Based on the Archbishop of Canterbury.

- White Bishop's Pawn. A Protestant minister; former fiance of the White Queen's Pawn who has been castrated by the Black Bishop's Pawn

- White Pawn. A servant pawn of unspecified allegiance.

Black House

- Black King. Based on King Philip IV of Spain.

- Black Queen. Based on Maria Anna of Spain, proposed bride of the White Knight

- Black Queen's Pawn. A Jesuitess.

- Black Knight. Based on Diego Sarmiento de Acuña, conde de Gondomar, who was the Spanish ambassador to London.

- Black Knight's Pawn. Suitor of the White Queen's Pawn and castrator of the White Bishop's Pawn.

- Black Duke. Based on Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares, a favourite of Felipe IV

- Black Bishop. Based on the Father-General of the Jesuits.

- Black Bishop's Pawn. A Jesuit.

- Black Jesting Pawn. A comic pawn of unspecified allegiance who teases a White Pawn. Does not appear in all versions of the play.

- Black Pawn. A servant pawn of unspecified allegiance.

Texts

A Game at Chess survives in nine different texts, each of which has its own unique characteristics. Gary Taylor thus calls the play "the most complicated editorial problem in the entire corpus of early modern drama, and one of the most complicated in English literature".[4] The play is unique in that it exists in more 17th-century manuscripts than it does printed editions (six extant manuscripts compared to three printed editions). Of the manuscripts, one is an authorial holograph, and three are the work of Ralph Crane, a professional scribe who worked for the King's Men in this era and who is thought to have prepared some of the play texts for the First Folio of Shakespeare's plays.

There are two major studies of the relationship between the texts: that of T.H. Howard Hill (1995), and Gary Taylor (2007); the studies give different names to the texts.

| Name (Howard-Hill) | Name (Taylor) | Current location | Provenance | Created by | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archdall (Ar.) | Crane1 | Folger Shakespeare Library | Once owned by Irish antiquary Mervyn Archdall | Ralph Crane (scribe) | Believed to be the earliest form of the play |

| Bridgewater-Huntington (B-H) | Bridgewater | Huntington Library | Bought from the Earl of Ellesmere's collection at Bridgewater House | Unidentified scribe | |

| Lansdowne (Ln.) | Crane2 | British Library | Lansdowne Collection | Ralph Crane (scribe) | |

| Malone (Ma.) | Crane3 | Bodleian Library | Formerly owned by William Hammond (d.1635) and John Pepys (d.1652) | Ralph Crane (scribe) | |

| First Quarto (Q1) | Okes | n/a | n/a | Nicholas Okes (printer) | |

| Second Quarto (Q2) | Okes2 | n/a | n/a | Nicholas Okes (printer) | A reprint of Q1 |

| Third Quarto (Q3) | Mathews/Allde | n/a | n/a | Augustine Mathews and Edward Allde (printers) | |

| Rosenbach (Rs.) | Rosenbach | Folger Shakespeare Library | Once owned by A.S.W. Rosenbach | Two unidentified scribes | |

| Trinity (Tr.) | MiddletonT | Trinity College, Cambridge | Perh. Patrick Young, librarian to King James I | Thomas Middleton (author) |

Synopsis

(Note: the act and scene divisions of this synopsis follow the edition of the play in "Women Beware Women and Other Plays," edited by Richard Dutton, Oxford 1999).

Prologue

The Prologue explains that the forthcoming stage play will be based on a game of chess, with chess pieces representing men and states. In the end, he says, "checkmate will be given to virtue’s foes."

Induction

The Ghost of Ignatius Loyola (founder of the Jesuit Order) expresses surprise at finding a rare corner of the world (England) where his order (the Catholic Church) has not been established. His servant, Error (a personification of deviance), who has been sleeping at Ignatius’ feet, wakes up and says that he has been dreaming of a game of chess where "our side"—the Blacks/Catholics—was set against the Whites/English. Ignatius says that he wants to see the dream so he can observe his side’s progress. The "pieces" (actors dressed as chess pieces) enter. Ignatius expresses contempt for his own followers and says that his true aim is to rule the entire world all by himself.

Act I

Scene 1

The Black Queen’s Pawn, a Jesuitess, attempts to corrupt the virginal White Queen’s Pawn (White Virgin). Faking tears, the Black Queen’s Pawn says she pities the White Virgin, whom she says will be "lost eternally," despite her beauty, because she is too "firm" (steadfast, loyal). The Black Bishop’s Pawn, a Jesuit, enters and takes over the attempt to corrupt the White Virgin, encouraging her to confess her sins to him. (Confession was a highly suspect Catholic practice in Renaissance England). The White Virgin confesses that she once considered entering into a love relationship, but didn’t actually follow through with it because the man she loved—the White Bishop’s Pawn—was castrated by the Black Knight’s Pawn. The Black Bishop’s Pawn gives the White Virgin a manual on moral instruction; she exits.

The Black Knight’s Pawn and his castrated victim, the White Bishop’s Pawn enter, exchange insults and exit.

The Black Knight enters. He notes that the "business of the universal monarchy" (i.e., the business of the Catholic Church) is going well, primarily because of his ability to trap souls by means of charm and deception. The White King’s Pawn—a spy, secretly employed by the Blacks—enters and issues a report. Gondomar praises the spy to his face, but calls him a fool after he exits.

Act II

Scene 1

The White Virgin enters reading the book the Black Bishop’s Pawn gave her. The book instructs her to obey her confessor in all things.

The Black Bishop’s Pawn enters reading a letter from the Black King, who says he wants to "capture" (seduce) the White Virgin himself. The Black Bishop’s Pawn says he will help the King, but intends to "taste" the White Virgin himself first.

The White Virgin greets the Black Bishop’s Pawn and begs him to give her an order so she can prove her virtue by obeying him. The Black Bishop’s Pawn commands her to kiss him; she objects; he scolds her disobedience and says that, as punishment for her refusal, she must now offer him her virginity. A noise from offstage provides a distraction, and the White Virgin manages to escape.

The Black Bishop enters with the Black Knight. The Black Bishop scolds his pawn, claiming that news of the fumbled seduction will cause a scandal for the Blacks. The Black Knight makes plans for a cover up. He orders the Black Bishop’s Pawn to flee, and says he will falsify documents to make it look as though the pawn was not in the vicinity when the incident took place. He also orders the Black Bishop to burn all of his files in case the house is searched (the files contain records of various other seductions and misdeeds).

At the end of the scene, the Black Knight’s Pawn enters and expresses remorse for castrating the White Bishop’s Pawn.

Scene 2

The Fat Bishop—a former member of the Black House, now employed by the Whites—gloats about his life: he has the freedom to gorge himself with food and sex on a regular basis. He is the author of several books criticizing the Black House.

The Black Knight Gondomar and the Jesuit Black Bishop enter. They curse the Fat Bishop and swear vengeance.

The White Virgin tells the White King James that the Black Bishop’s Pawn has tried to rape her. Confronted with the charges, the Black Knight calls the White Virgin a liar and produces falsified documents showing that the Black Bishop’s Pawn was out of town while the incident allegedly took place. The White King James reluctantly finds the White Virgin guilty of slander and rules that the Blacks may discipline her as they see fit. The Blacks decree that the White Virgin must fast for four days, kneeling for twelve hours a day in a room filled with Aretine's pictures (erotic Italian images with caption-poems by Pietro Aretino showing classical figures in various sexual positions).

Act III

Scene 1

The Fat Bishop expresses dissatisfaction with the White House; he wants more titles and honors.

The Black Knight gives the Fat Bishop a (fake) letter from Rome. The letter suggests that the Fat Bishop could become the next Pope if he switches back to the Black side. Excited by the letter, the Fat Bishop decides to burn all of the books he has written against the Whites and re-join the Blacks immediately.

The Black Knight’s Pawn enters and tells Gondomar that his plot has been foiled: upon investigation, the White Bishop’s Pawn discovered that the Black Bishop’s Pawn was, indeed, in town when the attempted rape of the White Virgin took place. The White Virgin is acquitted and released.

Angling to regain trust, the Black Queen’s Pawn praises the White Virgin’s virtue and claims responsibility for creating the distraction that enabled her escape during the attempted rape. The White Virgin is grateful.

The Black Knight reveals that the White King’s Pawn is a spy and "captures" him.

The Fat Bishop switches to the Black side and says he will immediately begin writing books against the Whites. In an aside, the Black Knight says he will flatter the Fat Bishop for a while and betray him as soon as he outlives his usefulness.

The (recently captured) White King’s Pawn asks the Black Knight how he will be rewarded for his service. Gondomar answers by sending him to "the bag" (a giant onstage bag for captured chess pieces, symbolic of Hell).

The Black Queen’s Pawn tells the White Virgin that she has seen the White Virgin’s future husband in a magic Egyptian mirror. The White Virgin is intrigued.

Scene 2

This scene is omitted in later versions of the play. It involves a good deal of sexual innuendo and physical action—much of it suggestive of anal intercourse, or "firking"—between a White Pawn, a "Black Jesting Pawn" and another Black Pawn. The following quote from the Black Jesting Pawn is indicative of the scene’s overall tenor: "We draw together now for all the world like three flies with one straw through their buttocks" (apparently, the Second Black Pawn is miming anal intercourse with the White Pawn, who is in turn miming anal intercourse with the Black jesting Pawn).

Scene 3

The Black Queen’s Pawn takes the White Virgin to a room where the magic Egyptian mirror is kept. The Black Bishop’s Pawn enters, disguised as the White Virgin’s rich future husband (the scene is arranged so that the White Virgin is only able to see the Black Bishop’s Pawn in the mirror). The White Virgin is fooled by the ruse.

Act IV

Scene 1

The Black Knight’s Pawn is still feeling guilty for castrating the White Bishop’s Pawn. He asks his confessor, the Black Bishop’s Pawn, for absolution. The Black Bishop’s Pawn says absolution is impossible.

The Black Queen’s Pawn enters with the White Virgin. They notice the Black Bishop’s Pawn, who is still disguised as the White Virgin’s rich future husband. The Black Queen’s Pawn takes the Black Bishop’s Pawn offstage to see the magic Egyptian mirror. When they return, the Black Bishop’s Pawn swears he saw an image of the White Virgin when he looked in the mirror—a sure sign that she will be his wife some day. He suggests that they have sex that very night, since they are destined for each other, rather than wasting time—but the White Virgin protests that she must save herself until she is actually his wife. The Black Bishop’s Pawn is distraught, but the Black Queen’s Pawn tells him not to worry—she will manage everything. In an aside, the Black Queen’s Pawn reveals that she plans to pull some sort of trick on the Black Bishop’s Pawn.

Scene 2

The Black Knight’s Pawn once again expresses remorse for castrating the White Bishop’s Pawn. The Black Knight scolds him for having such a thin skin; in a long speech, he boasts about the wide range of crimes he himself has committed—without compunction.

The Fat Bishop enters leafing through a book that list the fines to be paid in recompense for various sins (a couple of shillings for adultery, fivepence for fornication, etc.); he says he cannot find any fine for castration, which means that the Black Knight’s Pawn cannot be forgiven. The Black Knight’s Pawn is distraught; his conscience is plaguing him; he feels a strong desire for absolution. The Fat Bishop suggests that the only course of action is for the Black Knight’s Pawn to kill the White Bishop’s Pawn—then he would be guilty of murder, a crime that is forgivable because it is listed in the book. The Black Knight’s Pawn exits vowing to kill the White Bishop’s Pawn as soon as possible.

Scene 3

In this scene, which is performed in dumbshow, the Black Queen’s Pawn orchestrates a "bed trick"—she tricks the Black Bishop’s Pawn into having sex with her by leading him to believe that he is going to bed with the White Virgin.

Scene 4

The White Knight goes to the Black House for negotiations. (This represents Charles’ trip to Spain; Middleton implies that the trip was made for purely strategic purposes). The Black Knight Gondomar tells the White Knight Charles that he will do anything to please him.

The Fat Bishop attempts to capture the unprotected White Queen, but his attack is prevented by the White Bishop and the White King, who capture the Fat Bishop and send him to "the bag" (Hell).

Act V

Scene 1

The White Knight and the White Duke enter the Black court, which is decorated with statues and candles (indicative of Catholicism).

Scene 2

The Black Bishop’s Pawn—no longer in his "rich future husband" disguise—tells the White Virgin that he is the man she has spent the night with. The White Virgin insists (truthfully) that she spent the night alone. The Black Queen’s Pawn enters and reveals her bed trick: she was the Black Bishop’s Pawn’s bed partner, which means that the White Virgin’s virginity is, indeed, still intact.

The White Bishop’s Pawn and the White Queen capture the Black Bishop’s Pawn and the Jesuitess Black Queen’s Pawn and send them to the bag.

The Black Knight’s Pawn tries to murder the White Bishop’s Pawn, but his attempt is foiled by the White Virgin, who captures him and sends him to the bag.

Scene 3

The White Knight and the White Duke have just finished a decadent meal at the Black court. The Black Knight delivers a long speech boasting about the extravagancies of the meal. The White Knight says that the meal has not fully satisfied him; there are two things that he truly hungers for. The Black Knight says he will provide anything Charles desires if he agrees to switch to the Black side. Charles says the two things he desires are ambition and sex. The Black Knight makes two long speeches boasting about the Blacks’ sexual licentiousness and ambition to rule the world (at one point, he brags that six thousand skulls of babies, aborted by nuns, were found at the ruins of a nunnery—a testament to the Blacks’ sexual appetite). As soon as these crimes have been admitted, the White Knight reveals that he has only been stringing the Black Knight along in order draw him out. Thus, the game is won.

The White King appears with the rest of the White court; all of the remaining Blacks are sent to the bag.

Notes

- ↑ Melissa D. Aaron, Global Economics: A History of the Theatre Business, the Chamberlain's/King's Men, and Their Plays, 1599–1642, Newark, DE, University of Delaware Press, 2003; p. 120.

- ↑ Edward M. Wilson and Olga Turner, "The Spanish Protest Against A Game at Chesse," Modern Language Review 44 (1949), p. 480.

- ↑ "The Oxford Middleton Project". Thomas Middleton. The English Department at Florida State University. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Gary Taylor, 'A Game at Chess: General Textual Introduction', in Thomas Middleton and Early Modern Textual Culture: A Companion to the Collected Works (OUP, 2007), p. 712.

References

- Middleton, Thomas. A Game at Chess, edited by J. W. Harper. London: Ernest Behn Ltd., 1966 (Mermaid edition).

- Keenan, Siobhan. Acting Companies and Their Plays in Shakespeare's London. London: Arden, 2014.183–93.