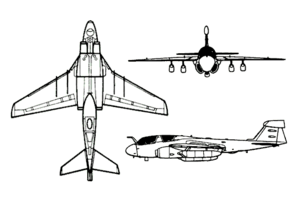

Northrop Grumman EA-6B Prowler

| EA-6B Prowler | |

|---|---|

| |

| A U.S. Navy EA-6B Prowler | |

| Role | Electronic warfare/Attack aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Grumman Northrop Grumman |

| First flight | 25 May 1968[1] |

| Introduction | July 1971 |

| Retired | 2015, U.S. Navy |

| Status | In service (USMC) |

| Primary users | United States Navy (historical) United States Marine Corps |

| Number built | 170 |

| Unit cost | |

| Developed from | Grumman A-6 Intruder |

The Northrop Grumman (formerly Grumman) EA-6B Prowler is a twin-engine, four-seat, mid-wing electronic warfare aircraft derived from the A-6 Intruder airframe. The EA-6A was the initial electronic warfare version of the A-6 used by the United States Marine Corps and United States Navy. Development on the more advanced EA-6B began in 1966. An EA-6B aircrew consists of one pilot and three Electronic Countermeasures Officers, though it is not uncommon for only two ECMOs to be used on missions. It is capable of carrying and firing anti-radiation missiles (ARM), such as the AGM-88 HARM missile.

Prowler has been in service with the U.S. Armed Forces since 1971. It has carried out numerous missions for jamming enemy radar systems, and in gathering radio intelligence on those and other enemy air defense systems. From the 1998 retirement of the United States Air Force EF-111 Raven electronic warfare aircraft, the EA-6B was the only dedicated electronic warfare plane available for missions by the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Marine Corps, and the U.S. Air Force until the fielding of the Navy's EA-18G Growler in 2009. Following its last deployment in late 2014, the EA-6B was withdrawn from U.S. Navy service in June 2015. The USMC plans to operate the Prowler until 2019.

Development

Origins

The EA-6A "Electric Intruder" was developed for the U.S. Marine Corps during the 1960s to replace its EF-10B Skyknights. The EA-6A was a direct conversion of the standard A-6 Intruder airframe, with two seats, equipped with electronic warfare (EW) equipment. The EA-6A was used by three Marine Corps squadrons during the Vietnam War. A total of 27 EA-6As were produced, with 15 of these being newly manufactured ones.[5] Most of these EA-6As were retired from service in the 1970s with the last few being used by the Navy with two electronic attack "aggressor" squadrons, with all examples finally retired in the 1990s.[6] The EA-6A was essentially an interim warplane until the more-advanced EA-6B could be designed and built.

The substantially redesigned and more advanced EA-6B was developed beginning in 1966 as a replacement for EKA-3B Skywarriors for the U.S. Navy. The forward fuselage was lengthened to create a rear area for a larger four-seat cockpit, and an antenna fairing was added to the tip of its vertical stabilizer.[5] Grumman was awarded a $12.7 million contract to develop an EA-6B prototype on 14 November 1966.[7] The Prowler first flew on 25 May 1968, and it entered service on aircraft carriers in July 1971.[8] Three prototype EA-6Bs were converted from A-6As, and five EA-6Bs were developmental airplanes. A total of 170 EA-6B production aircraft were manufactured from 1966 through 1991.[6]

The EA-6B Prowler is powered by two Pratt & Whitney J52 turbojet engines, and it is capable of high subsonic speeds. Due to its extensive electronic warfare operations, and the aircraft's age (produced until 1991), the EA-6B is a high-maintenance aircraft, and has undergone many frequent equipment upgrades. Although designed as an electronic warfare and command-and-control aircraft for air strike missions, the EA-6B is also capable of attacking some surface targets on its own, in particular enemy radar sites and surface-to-air missile launchers. In addition, the EA-6B is capable of gathering electronic signals intelligence.

The EA-6B Prowler has been continually upgraded over the years. The first such upgrade was named "expanded capability" (EXCAP) beginning in 1973. Then came "improved capability" (ICAP) in 1976 and ICAP II in 1980. The ICAP II upgrade provided the EA-6B with the capability of firing Shrike missiles and AGM-88 HARM missiles.[6]

Advanced Capability EA-6B

The Advanced Capability EA-6B Prowler (ADVCAP) was a development program initiated to improve the flying qualities of the EA-6B and to upgrade the avionics and electronic warfare systems. The intention was to modify all EA-6Bs into the ADVCAP configuration, however the program was removed from the Fiscal Year 1995 budget due to financial pressure from competing Department of Defense acquisition programs.

The ADVCAP development program was initiated in the late 1980s and was broken into three distinct phases: Full-Scale Development (FSD), Vehicle Enhancement Program (VEP) and the Avionics Improvement Program (AIP).

FSD served primarily to evaluate the new AN/ALQ-149 Electronic Warfare System. The program utilized a slightly modified EA-6B to house the new system.

The VEP added numerous changes to the aircraft to address deficiencies with the original EA-6B flying qualities, particularly lateral-directional problems that hampered recovery from out-of-control flight. Bureau Number 158542 was used. Changes included:

- Leading edge strakes (to improve directional stability)

- Fin pod extension (to improve directional stability)

- Ailerons (to improve slow speed lateral control)

- Re-contoured leading edge slats and trailing edge flaps (to compensate for an increase in gross weight)

- Two additional wing stations on the outer wing panel (for jamming pods only)

- New J52-P-409 engines (increased thrust by 2,000 lbf (8.9 kN) per engine)

- New digital Standard Automatic Flight Control System (SAFCS)

The added modifications increased the aircraft gross weight approximately 2,000 lb (910 kg) and shifted the center of gravity 3% MAC aft of the baseline EA-6B. In previous models, when operating at sustained high angles of attack, fuel migration would cause additional shifts in CG with the result that the aircraft had slightly negative longitudinal static stability. Results of flight tests of the new configuration showed greatly improved flying qualities and the rearward shift of the CG had minimal impact.

The AIP prototype (bureau number 158547) represented the final ADVCAP configuration, incorporating all of the FSD and VEP modifications plus a completely new avionics suite which added multi-function displays to all crew positions, a head-up display for the pilot, and dual Global Positioning/Inertial navigation systems. The initial joint test phase between the contractor and the US Navy test pilots completed successfully with few deficiencies.

After the program was canceled, the three experimental Prowlers, BuNo 156482, 158542 and 158547, were mothballed until 1999. During the next several years, the three aircraft were dismantled and reassembled creating a single aircraft, b/n 158542, which the Navy dubbed "FrankenProwler". It was returned to active service 23 March 2005.[9]

Improved Capability (ICAP)

Northrop Grumman received contracts from the U.S. Navy to deliver new electronic countermeasures gear to Prowler squadrons; the heart of each ICAP III set consists of the ALQ-218 receiver and new software that provides more precise selective-reactive radar jamming and deception and threat location. The ICAP III sets also are equipped with the Multifunction Information Distribution System (MIDS), which includes the Link 16 data link system. Northrop has delivered two lots and will be delivering two more beginning in 2010.[10] The majority of EA-6B Prowlers in service today are the ICAP II version, carrying the ALQ-99 Tactical Jamming System.

Design

Designed for carrier-based and advanced base operations, the EA-6B is a fully integrated electronic warfare system combining long-range, all-weather capabilities with advanced electronic countermeasures.[11] A forward equipment bay and pod-shaped fairing on the vertical fin house the additional avionics equipment. It has been the primary electronic warfare aircraft for the U.S Navy and U.S. Marine Corps. The EA-6B's primary mission is to support ground-attack strikes by disrupting enemy electromagnetic activity. As a secondary mission it can also gather tactical electronic intelligence within a combat zone, and another secondary mission is attacking enemy radar sites with anti-radiation missiles.

The Prowler has a crew of four, a pilot and three Electronic Countermeasures Officers (known as ECMOs). Powered by two non-afterburning Pratt & Whitney J52-P-408A turbojet engines, it is capable of speeds of up to 590 mph (950 km/h) with a range of 1,140 miles (1,840 km).

Design particulars include the refueling probe being asymmetrical, appearing bent to the right. It contains an antenna near its root. The canopy has a shading of gold to protect the crew against the radio emissions that the electronic warfare equipment produces.

Operational history

The EA-6B entered service with Fleet Replacement Squadron VAQ-129 in September 1970, and Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 132 (VAQ-132) became the first operational squadron, in July 1971. This squadron began its first combat deployment to Vietnam on America 11 months later, soon followed by VAQ-131 on Enterprise and VAQ-134 on Constellation.[12]

Two squadrons of EA-6B Prowlers flew 720 sorties during the Vietnam War in support of US Navy attack aircraft and USAF B-52 bombers. During the 1983 invasion of Grenada, four Prowlers supported the operation from USS Independence (CV-62). Following the Achille Lauro hijacking, on 10 October 1985 Prowlers from USS Saratoga (CV-60) provided ESM support during the interception of the EgyptAir 737 carrying four of the hijackers.[13]

Prowlers jammed Libyan radar during Operation El Dorado Canyon in April 1986. Prowlers from USS Enterprise (CVN-65) jammed Iranian Ground Control Intercept radars, surface-to-air missile guidance radars and communication systems during Operation Praying Mantis on 18 April 1988.[13]

A total of 39 EA-6B Prowlers were involved in Operation Desert Storm in 1991, 27 from six aircraft carriers and 12 from USMC bases. During 4,600 flight hours, Prowlers fired over 150 HARM missiles. Navy Prowlers flew 1,132 sorties and USMC flew 516 with no losses.[13]

With the retirement of the EF-111 Raven in 1998, the EA-6B was the only dedicated aerial radar jammer aircraft of the U.S. Armed Forces, until the fielding of the Navy's EA-18G Growler in 2009. The EA-6B has been flown in almost all American combat operations since 1972, and is frequently flown in support of the U.S. Air Force missions.

In 2001, 124 Prowlers remained, divided between twelve Navy, four Marine, and four joint Navy-Air Force "Expeditionary" squadrons. A Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) staff study recommended that the EF-111 Raven be retired to reduce the types of aircraft dedicated to the same mission, which led to an Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) program memorandum to establish 4 land based "expeditionary" Prowler squadrons to meet the needs of the Air Force.[14]

Though once considered being replaced by Common Support Aircraft, that plan failed to materialize. In 2009, the Navy EA-6B Prowler community began transitioning to the EA-18G Growler, a new electronic warfare derivative of the F/A-18F Super Hornet. All but one of the active duty Navy EA-6B squadrons were based at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island. VAQ-136 was stationed at Naval Air Facility Atsugi, Japan, as part of Carrier Air Wing 5, the forward deployed naval forces (FDNF) air wing that embarks aboard the Japan-based George Washington. VAQ-209, the Navy Reserve's sole EA-6B squadron, was stationed at Naval Air Facility Washington, Maryland. All Marine Corps EA-6B squadrons are located at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina.

In 2013, the USN planned to fly the EA-6B until 2015, while the USMC expect to phase out the Prowler in 2019.[15] The last Navy deployment was on George H.W. Bush in November 2014, with VAQ-134.[16][17] The last Navy operational flight took place on 27 May 2015.[18] Electronic Attack Wing, U.S. Pacific Fleet (CVWP), hosted a retirement commemoration for the EA-6B from 25 to 27 June 2015 at NAS Whidbey Island.[19]

Operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria

In 2007, it was reported that the Prowler has been used in anti-improvised explosive device operations in the conflict in Afghanistan for several years by jamming remote detonation devices such as garage door openers or cellular telephones.[20] Two Prowler squadrons were also based in Iraq, working with the same mission.[21] According to Chuck Pfarrer in his book SEAL Target Geronimo, an EA-6B was also used to jam Pakistani radar and assist the 2 MH-60 Black Hawk stealth helicopters and 2 Chinook helicopters raiding Osama Bin Laden's compound in Operation Neptune Spear.[22] The Department of Defense disputed certain aspects of his book, though not specifically the mention of EA-6B involvement.

VMAQ-3 began flying Prowler missions against Islamic State militants over Iraq in June 2014. Once Operation Inherent Resolve began in August, VMAQ-4 took over. The Prowlers were the first Marine Corps aircraft in Syria and support strike packages, air drops, and electronic warfare requirements against militants. By January 2015, the five aircraft of VMAQ-4 had flown 800 hours during 110 sorties in support of operations in both countries, including supporting coalition airstrikes and providing EW support for Iraqi Army forces to degrade enemy systems. Marine Prowlers had not dropped munitions themselves and host nations basing them have not been revealed.[23]

In April 2016, a squadron of EA-6B Prowlers from Marine Corps Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 4, based at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, was deployed to Incirlik Air Base, Turkey for operations over Syria. U.S. European Command confirmed that the deployment was expected to last through September 2016. The Center for Strategic and International Studies suggested that the Prowlers may be used to prevent Russian and Syrian air defense systems from tracking U.S. and coalition aircraft.[24]

Operators

The EA-6B Prowler is operated by the U.S. Armed Forces, and has squadrons in both the U.S. Marine Corps and Navy.

USMC squadrons

VMAQ squadrons operate the EA-6B Prowler.[25] Each of the four squadrons operates five aircraft and are land-based, although they are capable of operating aboard U.S. Navy aircraft carriers and have done so in the past.[26][27]

In 2013, VMAQ-1 converted from an active to a training squadron as the USN stopped training on the Prowler and switched over to the Growler. The Marine Training squadron first received students for training in October 2013 and produced its first training flights in April 2014.[28]

| Squadron Name | Insignia | Nickname | Dates operated | Senior Command | Station |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In 2008, the USMC was investigating an electronic attack role for the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II to replace their Prowlers.[33] The Marines plan to begin retiring the EA-6 in 2016 and replace them with the Marine Air-Ground Task Force Electronic Warfare (MAGTF-EW) concept, which calls for a medium to high-altitude long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicle to off-load at least some of the electronic warfare mission to.[34]

USN squadrons

While in U.S. Navy service four EA-6B Prowlers were typically assigned to a Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron. These Navy Electronic Attack squadrons carried the letters VAQ (V-fixed wing, A-attack, Q-electronic); most of these squadrons were carrier-based, while others were "expeditionary" and deployed to overseas land bases.[11]

| Squadron Name | Insignia | Nickname | Dates Operated | Carrier air wing | Station | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAQ-129 | | Vikings | 1971-2015 | Fleet Replacement Squadron | NAS Whidbey Island[35] | Trained both Marine, Air Force, and Navy crews in the EA-6B and the EA-18G |

| VAQ-130 | | Zappers | 1975–2011 | CVW-3 | NAS Whidbey Island[36] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G |

| VAQ-131 | | Lancers | 1971-2015 | CVW-2 | NAS Whidbey Island[37] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G |

| VAQ-132 | | Scorpions | 1971–2009 | N/A[38] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G | |

| VAQ-133 | | Wizards | 1971-2014 | CVW-9 | NAS Whidbey Island[39] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G |

| VAQ-134 | | Garudas | 1972-2015 | CVW-8 | NAS Whidbey Island[40] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G.[41] |

| VAQ-135 | | Black Ravens | 1973–2010 | NAS Whidbey Island[42] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G | |

| VAQ-136 | | Gauntlets | 1973–2012 | NAS Whidbey Island[43] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G | |

| VAQ-137 | | Rooks | 1973–2012 | CVW-1 | NAS Whidbey Island[44] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G |

| VAQ-138 | | Yellowjackets | 1976–2009 | N/A[45] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G | |

| VAQ-139 | | Cougars | 1983–2011 | CVW-17 | NAS Whidbey Island[46] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G |

| VAQ-140 | | Patriots | 1985-2014 | CVW-7 | NAS Whidbey Island[47] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G |

| VAQ-141 | | Shadowhawks | 1987–2009 | CVW-5 | Naval Air Facility (NAF) Atsugi[48] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G |

| VAQ-142 | | Gray Wolves | 1997-2015 | CVW-11 | NAS Whidbey Island[49] | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G |

| VAQ-209 | | Star Warriors | 1977–2013 | Reserve Tactical Support Wing | NAS Whidbey Island | EA-6B replaced by EA-18G |

Disestablished Squadrons

VAQ-128: Established as an expeditionary squadron in October 1997, utilizing the insignia and heritage of the former A-6 Intruder Fleet Replacement Squadron at NAS Whidbey Island. Disestablished in September 2004 due to budget reductions.

VAQ-309: Established as a Naval Air Reserve Force squadron at NAS Whidbey Island in 1979 with EA-6A aircraft, transitioning to the EA-6B in 1989 as part of Carrier Air Wing Reserve THIRTY (CVWR-30). Disestablished on 31 Dec 1994 following the decommissioning of CVWR-30 due to budget cuts; aircraft returned to the Regular Navy.

Notable accidents

While no Prowler has ever been lost in combat, nearly fifty of the 170 built were destroyed in various accidents as of 2013.[50] In 1998, a memorial at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island was dedicated to 44 crew members lost in EA-6B aircraft accidents.[51]

- On 26 May 1981, a USMC EA-6B crashed onto the flight deck of Nimitz and caused a fire, killing 14 crew men and injuring 45 others.[52][53] The Prowler was running out of fuel after a missed approach ("bolter" in Navy parlance), and its crash and the subsequent fire and explosions destroyed or damaged 11 other aircraft.[54]

- A USMC EA-6B Prowler, BuNo 163045, from VMAQ-2 caused the Cavalese cable car disaster on 3 February 1998, accidentally cutting the cables of a cableway in Italy during a low level flight in mountainous terrain, killing 20 people.

- On 10 November 1998, a USN EA-6B landed on a Lockheed S-3 Viking during night landing qualifications on Enterprise; four crew members were killed.[55]

Aircraft on display

- EA-6A

- 147865 – MCAS Cherry Point, Cherry Point, North Carolina.[56]

- 148618 – NAS Key West, Big Coppitt Key, Florida.[57]

- 149475 - Wisconsin National Guard Memorial Library and Museum, Volk Field, Camp Douglas, Wisconsin.[58]

- 156984 - Warner Museum of Aviation and Transportation, Sioux City, Iowa.[59]

- EA-6B

- One aircraft on display at Hickory Aviation Museum, Hickory, NC from Cherry Point, NC.

- 158542 "FrankenProwler made from three ADVCAP airframes into one craft on display Pima Air & Space Museum, Tucson, Arizona.

- 162935 on display at the USS Midway Museum, San Diego, CA.

Specifications (EA-6B)

Data from US Navy Fact File,[11] US Navy history page[26]

General characteristics

- Crew: four (one pilot, three electronic countermeasures officers)

- Length: 59 ft 10 in (17.7 m)

- Wingspan: 53 ft (15.9 m)

- Height: 16 ft 8 in (4.9 m)

- Wing area: 528.9 ft² (49.1 m²)

- Empty weight: 31,160 lb (15,130 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 61,500 lb (27,900 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney J52-P408A turbojet, 10,400 lbf (46 kN) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 566 knots (651 mph, 1,050 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 418 kt (481 mph, 774 km/h)

- Range: 2,022 mi (tanks kept) / 2,400 mi (tanks dropped) (3,254 km / 3,861 km)

- Service ceiling: 37,600 ft (11,500 m)

- Rate of climb: 12,900 ft/min (65 m/s)

- Wing loading: 116 lb/ft² (560 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.34

Armament

- Hardpoints: 5 total: 1× centreline/under-fuselage plus 4× under-wing pylon stations with a capacity of 18,000 pounds (8,164.7 kg) and provisions to carry combinations of:

- Missiles: Up to 4× AGM-88 HARM Anti-radiation missiles (2x typically carried)

- Other:

- Up to 5× 300 US gallons (1,100 L) external drop tanks

- Up to 5× AN/ALQ-99 Tactical Jamming System (TJS) external pods

- AN/ALE-43(V)1&4 Bulk Chaff Dispensing System pod

- AN/AAQ-28(V) LITENING targeting pod (USMC only)

Avionics

- AN/ALQ-218 Tactical Jamming System Receiver

- AN/USQ-113 Communications Jamming System

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

- Notes

- ↑ "EA-6B Prowler". Warfighters Encyclopedia. Naval Air Systems Command. Archived from the original on 5 November 2004.

- ↑ "EA-6B Prowler". Federation of American Scientists. 11 October 1998. Archived from the original on 5 December 1998.

- ↑ "14 Die as Navy jet crashes into planes on USS Nimitz". The Miami News. Miami, Florida. 27 May 1981.

- ↑ "Desert War Proved Need for Improved Arsenal". Gazette Telegraph. Colorado Springs. 5 December 1973. p. 8C.

- 1 2 Frawley, Gerald (2002). "Grumman EA-6B Prowler". The International Directory of Military Aircraft, 2002/2003. Aerospace Publications. ISBN 1-875671-55-2.

- 1 2 3 Eden, Paul (2004). "Grumman EA-6B Prowler". Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. Amber Books. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- ↑ "EA-6B Prototype". Naugatuck Daily News. 17 November 1966. p. 4.

- ↑ Paul Eden and Soph Moeng, eds. (2002). The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. London: Amber Books Ltd. p. 1152. ISBN 0-7607-3432-1.

- ↑ Harvill, Brian (29 April 2005). "VAQ-141 'FrankenProwler' rejoins the fleet". Northwest Navigator. Archived from the original on 24 November 2007.

- ↑ "U.S. Navy Awards Northrop Grumman $125 Million Contract to Produce Fourth Lot of Airborne Electronic Attack Systems" (Press release). Northrop Grumman. 29 September 2008.

- ↑ Bowers, Peter M. United States Navy Aircraft since 1911. Annapolis, Maryland, USA: Naval Institute Press, 1990, p. 274. ISBN 0-87021-792-5.

- 1 2 3 Laur, Timothy M. (July 1998). Encyclopedia of modern us military weapons. Berkley Trade. pp. 63–65. ISBN 0425164373.

- ↑ "Electronic Warfare: EA-6B Aircraft Modernization and Related Issues for Congress". congressionalresearch.com. 3 December 2001.

- ↑ Book, Sue (13 June 2013). "Marines to assume EA-6B Prowler training". Sun Journal. New Bern, North Carolina.

- ↑ "EA-6B PROWLER's FINAL PROWL". Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ↑ http://www.whidbeynewstimes.com/opinion/282766971.html

- ↑ Navy’s EA-6B Prowler Takes Last Active Duty Flight Before Sunset Ceremony - News.USNI.org, 28 May 2015

- ↑ Prowler Retires Following 45 Years of Naval Service, story NNS150630-18 by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class John Hetherington, U.S. Navy Public Affairs Support Element West, Det. Northwest, 30 June 2015.

- ↑ "Navy Takes Aim at Roadside Bombs". Military.com. Military Advantage. Associated Press. 12 June 2007.

- ↑ "Planes on the prowl for roadside bombs". CNN. 13 June 2007. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007.

- ↑ SEAL Target Geronimo: The Inside Story of the Mission to Kill Osama bin Laden. Pfarrer, Chuck. Macmillan, Nov 8, 2011.

- ↑ Marine Prowlers fight Islamic State over Iraq, Syria - MarineCorpstimes.com, 18 January 2014

- ↑ "Marine Prowlers deploy to Turkey for fight against ISIS". Marine Corps Times. 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "E/A-6B Prowler". Northrop Grumman. Archived from the original on 17 March 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- 1 2 "EA-6B Prowler". Naval Historical Center. United States Department of the Navy. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ↑ "EA-6B Prowler". Intelligence Resource Program. Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- ↑ Burgess, Richard R. (15 April 2014). "Marine Training Squadron Produces Its First Prowler Crews". www.seapowermagazine.org. SEAPOWER Magazine. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ "Marine Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 1". United States Marine Corps. Retrieved 16 March 2007.

- ↑ "Marine Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 2". United States Marine Corps. Retrieved 16 March 2007.

- ↑ "Marine Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 3". United States Marine Corps. Retrieved 16 March 2007.

- ↑ "Marine Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 4". United States Marine Corps. Retrieved 16 March 2007.

- ↑ "Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Transition Plan" (PDF). USMC. 15 May 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2008.

- ↑ US Marines in market for Reaper-sized UAS - Flightglobal.com, 14 November 2014

- ↑ "VAQ-129 Vikings". United States Navy. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ↑ "History – Electronic Attack Squadron 130". Electronic Attack Squadron 130. United States Navy. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ↑ "VAQ-131 Lancers Command History". VAQ-131 Lancers. United States Navy. Archived from the original on 17 July 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ↑ "VAQ-131 Lancers Command History". VAQ-131 Lancers. United States Navy. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "VAQ-133 official website". United States Navy. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ↑ "VAQ-134 official website". United States Navy. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ↑ BURGESS, RICHARD (25 October 2014). "Navy Delays Formation of Expeditionary EA-18G Squadron". Archived from the original on 25 October 2014.

- ↑ "VAQ-135 official website". United States Navy. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ↑ "Northwest Navigator". United States Navy. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ "VAQ-137 official website". United States Navy. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ↑ "VAQ-138 official website". United States Navy. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "VAQ-139 official website". United States Navy. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ↑ "VAQ-140 official website". United States Navy. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ↑ "EA-18G Growlers to replace EA-6B Prowlers". United States Navy. 3 February 2012. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ "VAQ-142 official website". United States Navy. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ↑ 49 losses from 1971 to 2013 by manual count from a list of bureau numbers with dates.

- ↑ Offley, Ed (28 August 1998). "Memorial honors 44 EA-6B Prowler crewmen". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ↑ Arendes, Ahron (29 May 2003). "Nimitz Remembers Lives Lost During 1981 Flight Deck Crash". USS Nimitz (CVN 68) Navy NewsStand. United States Navy.

- ↑ Anderson, Kurt; Beaty, Jonathan (8 June 1981). "Night of Flaming Terror". TIME in partnership with CNN. Time. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ↑ Gero, David (1999). Military Aviation Disasters. Yeovil: Haynes. pp. 131–132. ISBN 1-85260-574-X.

- ↑ "Navy Flying Accident Leaves at Least 1 Dead". The New York Times. 10 November 1998.

- ↑ "A-6 Intruder/147865." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "A-6 Intruder/148618." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "A-6 Intruder/149475." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "A-6 Intruder/156984." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2015.

- Bibliography

- Donald, David ed. "Northrop Grumman EA-6B Prowler", Warplanes of the Fleet. AIRtime, 2004. ISBN 1-880588-81-1.

- Miska, Kurt H. "Grumman A-6A/E Intruder; EA-6A; EA6B Prowler (Aircraft in Profile number 252)". Aircraft in Profile, Volume 14. Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1974, p. 137–160. ISBN 0-85383-023-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grumman EA-6 Prowler. |

- EA-6B Prowler Fact File and EA-6B history on Navy.mil

- EA-6B Prowler on GlobalSecurity.org

- EA-6B Gondola Mishap, Cavalese, Italy, 3 February 1998, Aviation Safety Consulting Services,