Aldus Manutius

| Aldus Manutius | |

|---|---|

Aldus Pius Manutius | |

| Born |

Aldo Manuzio Fifteenth century |

| Died | 1515 |

| Nationality | Venetian |

| Other names | Aldus Manutius the Elder |

| Occupation | humanist who became a printer and publisher |

| Known for | founding the Aldine Press at Venice |

Aldus Pius Manutius (Italian: Aldo Manuzio; 1449 – February 6, 1515)[1] was an Italian humanist who became a printer and publisher when he founded the Aldine Press at Venice. He is sometimes called "the Elder" to distinguish him from his grandson Aldus Manutius the Younger.

His publishing legacy includes the distinctions of inventing italic type, establishing the modern use of the semicolon, developing the modern appearance of the comma,[2] and introducing inexpensive books in small formats bound in vellum that were read much as modern paperbacks are.[3]

Early life

Manutius was born in Bassiano, in the Papal States, in what is now the province of Latina, some 100 km south of Rome, during the Italian Renaissance period.

His family was well off and Manutius was educated as a humanistic scholar, studying Latin in Rome, under Gasparino da Verona, and Greek at Ferrara, under Guarino da Verona.

In 1482 he went to reside at Mirandola with his old friend and fellow student, the illustrious Giovanni Pico. There he stayed two years, pursuing his studies in Greek literature. Before Pico moved to Florence, he procured for Manutius the post of tutor to his nephews, Alberto and Leonello Pio, princes of Carpi.[4] Alberto Pio supplied Manutius with funds for starting his printing press and gave him lands at Carpi.[5]

Manutius became a tutor to some of the great Italian ducal families during his early career.

Accomplishments as publisher

The leading publisher and printer of the Venetian High Renaissance, Aldus set up a definite scheme of book design, produced the first italic type, introduced small and handy pocket editions (octavos) of the classics, and applied several innovations in binding technique and design for use on a broad scheme.

He commissioned Francesco Griffo to cut a slanted type known today as italic.

He and his grandson Aldus Manutius, the Younger, also a printer, are credited with introducing a standardized system of punctuation.

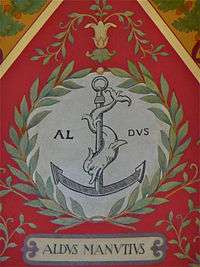

Imprint and motto

In 1501, Aldus began to use, as his publisher's device, the image of a dolphin wrapped around an anchor.[6] His editions of the classics were so highly respected that almost immediately the dolphin-and-anchor device was pirated by French and Italian publishers. More recently, the device has been used by the nineteenth-century London firm of William Pickering, and by Doubleday. Aldus adapted the image from the reverse of ancient Roman coins issued during the reigns of the Emperors Titus and Domitian, AD 80–82.[7] The dolphin and anchor emblem is associated with "Festina lente" (Hasten slowly), a motto that Aldus had begun to use as early as 1499, after receiving a Roman coin from Pietro Bembo, which bore the emblem and motto.[8]

Typefaces

For his series of pocket-sized editions of the classics, Manutius designed a new font in which the letters were inclined which he called "italic" in reference to classical Italy. Despite trying to have the font patented, he could not stop printers outside Venice from copying it, leading to the font's popularity outside of Italy.[9] Type designs based on work designed by Francesco Griffo and commissioned by Aldus Manutius include Bembo, Poliphilus, and Garamond.

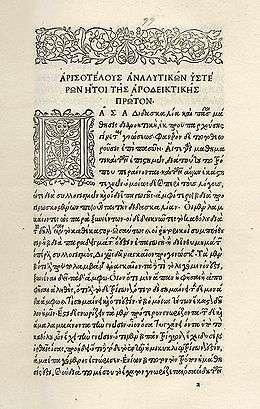

Greek classics

Manutius desired to preserve ancient Greek literature by printing editions of its greatest books. He introduced personal or pocket editions of the classics in Greek and Latin that all could own. Scholars admired his editions and the work that he undertook to edit these ancient texts.

Before Manutius, four Italian towns had printed editions of ancient Greek texts: Milan, with the grammar of Constantine Lascaris, Aesop, Theocritus, a Greek Psalter, and Isocrates, between 1476 and 1493; Venice, with the Erotemata of Manuel Chrysoloras in 1484; Vicenza, with reprints of Lascaris' grammar and the Erotemata, in 1488 and 1490; and Florence, with Lorenzo de Alopa's Homer, in 1488. Of these works, only three, the Milanese Theocritus and Isocrates, and the Florentine Homer, were classics.

Manutius settled in Venice in 1490. The city by this time was not only a major printing center but it also had a large library of Greek manuscripts from Constantinople and a population of Greeks who could assist with their translation. He soon afterward printed editions of Hero and Leander by Musaeus Grammaticus, the Galeomyomachia, and the Greek Psalter. He called these "Precursors of the Greek Library." He began gathering Greek scholars and compositors around him, employing as many as 30 Greeks in his print shop and speaking Greek at home. Instructions to typesetters and binders were given in Greek. The prefaces to his editions were written in Greek. Greeks from Crete collated manuscripts, read proofs, and gave samples of calligraphy for casts of Greek type.

In 1495, Manutius issued the first volume of his edition of Aristotle. Four more volumes completed the work in 1497–1498. Nine comedies of Aristophanes appeared in 1498. Thucydides, Sophocles, and Herodotus followed in 1502; Xenophon's Hellenics and Euripides in 1503; Demosthenes in 1504. It is possible that during this period, in his printing works, Hieromonk Makarije was educated, who would later found the Obod printing works of Cetinje and print the first books in Serbian and Romanian.[10]

The Second Italian War, which pressed heavily on Venice at this time, suspended Manutius' labours for a time. In 1508 he resumed his series with an edition of the minor Greek orators, however, and in 1509 appeared the lesser works of Plutarch. Then came another stoppage when the League of Cambrai drove Venice back to her lagoons, and all the forces of the republic were concentrated on a life-or-death struggle with the allied powers of Europe. In 1513 Manutius reappeared with an edition of Plato, which he dedicated to Pope Leo X in a preface that compares the miseries of warfare and the woes of Italy, with the sublime and tranquil objects of the student's life. Pindar, Hesychius, and Athenaeus followed in 1514. At the end of his life, Manutius had begun an edition of the Septuagint, the first to be published; it appeared posthumously in 1518.

In addition to editing Greek classics from manuscripts, Manutius re-printed editions of classics that had originally been published in Florence, Rome, and Milan, at times correcting and improving the texts.

In order to promote Greek studies, Manutius founded an academy of Hellenists in 1502 called the "New Academy." Its rules were written in Greek, its members were obliged to speak Greek, their names were Hellenized, and their official titles were Greek. Members of the "New Academy" included Desiderius Erasmus and the Englishman Thomas Linacre.

When Manutius died in Venice, bequeathing Greek literature as an inalienable possession to the world, he was a poor man. Manutius' successors continued his enthusiasm for Greek literature by printing the first editions of Pausanias, Strabo, Aeschylus, Galen, Hippocrates, and Longinus.

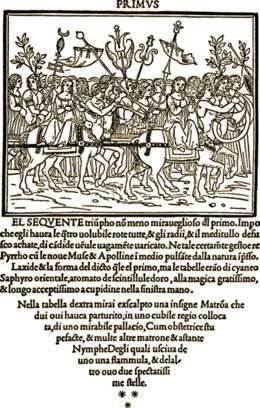

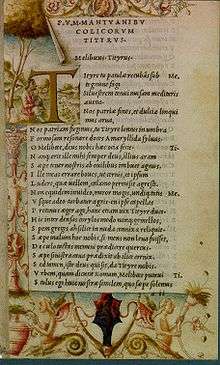

Latin classics

Manutius' press also published Latin and Italian classics. The Asolani of Bembo, the collected writings of Poliziano, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Dante's Divine Comedy, Petrarch's poems, a collection of early Latin poets of the Christian era, the letters of the Pliny the Younger, the poems of Iovianus Pontanus, Jacopo Sannazaro's Arcadia, Quintilian, Valerius Maximus, and the Adagia of Erasmus were printed, either in first editions, or with a beauty of type and paper never reached before, between the years 1495 and 1514. For these Italian and Latin editions, Manutius had the elegant type struck which bears his name. It is said to have been copied from Petrarch's handwriting, and was cast under the direction of Francesco da Bologna, who has been wrongly identified by Antonio Panizzi with Francia the painter.

Manutius strove for excellence in typography and book design while at the same time striving to create inexpensive editions. His great undertaking was carried on under continual difficulties, arising from strikes among his workmen, the piracies of rivals, and the interruptions of war.

The 1501 Virgil, which introduced the use of italic print, was produced in higher-than-normal print runs (1,000 rather than the usual 200 to 500 copies).

Marriage and personal life

In 1505, Manutius married Maria, daughter of Andrea Torresani[11] of Asola. Torresani had already bought the press established by Nicholas Jenson at Venice. Therefore, Manutius' marriage combined two important publishing firms. Henceforth the names Aldus and Asolanus were associated on the title pages of the Aldine publications; and after Manutius' death in 1515, Torresani and his two sons carried on the business during the minority of Manutius' children. The device of the dolphin and the anchor, and the motto festina lente, which indicated quickness combined with firmness in the execution of a great scheme, were never wholly abandoned by the Aldine Press until the expiration of their firm in the third generation.

Innovations

Manutius wanted to create an octavo book format that gentlemen of leisure could easily transport in a pocket or a satchel, the long, narrow libri portatiles of his 1503 catalogue, forerunners of the modern pocket book.[12] Manutius' edition of Virgil's Opera (1501) was the first octavo volume that he produced.

In his prefatory letter to Pietro Bembo in the 1514 Virgil, Aldus recorded that he "took the small size, the pocket book formula, from your library, or rather from that of your most kind father".[13]

Manutius created the italic typeface style, for the exclusive use of which for many years he obtained a patent, though the honour of the invention is more probably due to his typefounder, Francesco Griffo, than to him. His typefaces were all designed and cut by the brilliant Griffo, a punchcutter who created the first Roman type cut from study of classical Roman capitals. He did not use his italic typeface for emphasis as we do today, however, but rather for its narrow and compact letterforms, which allowed for more economical use of space (more words per page, fewer pages, lower production costs), thus enabling the printing of pocket-sized books.

Manutius is also believed to have been the first typographer to use a semicolon.[14] In 1566, his grandson, Aldus Manutius the Younger, produced Orthographiae Ratio, the first book on the principles of punctuation.[15]

Influence in the modern era

Manutius' name is the inspiration for Progetto Manuzio, an Italian free text project similar to Project Gutenberg.

The novel Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore by Robin Sloan features a fictionalized version of Aldus Manutius, as well as a fictional secret society devoted to him. One of the novel's characters, Griffo Gerritszoon, designs a fictitious font called "Gerritszoon" which is preinstalled on every Mac, in allusion to Manutius' associate Francesco Griffo, the designer of italic type.

Aldus, a software company founded in Seattle in 1985, that created PageMaker for the Apple Macintosh, is named after Manutius and used his profile as part of their company logo. Aldus was purchased by Adobe Systems in 1994.

The Aldus Journal of Translation, a publication from Brown University, is named after Aldus Manutius.

See also

- Printing

- Aldine Press

- History of Western typography

- Aldus — a typeface created by Hermann Zapf and named after Aldus Manutius.

- Aldus — a software company in Seattle named after Manutius that created PageMaker for the Apple Macintosh

Notes

- ↑ "Pay attention: it's important!". The Telegraph. Retrieved November 9, 2010. "This is a celebration of punctuation, full of jokes and anecdotes and information. It also introduces us to a new hero, and, as a fitting act of deference, I am going to put down a colon before writing his name: Aldus Manutius the Elder. This Venetian printer, who lived from 1450 to 1515, was the inventor of the italic typeface and also the first to use the semicolon."

- ↑ Truss 2004, p. foreword.

- ↑ Schuessler, Jennifer (February 26, 2015). "A Tribute to the Printer Aldus Manutius, and the Roots of the Paperback". The New York Times.

- ↑ Herbermann 1913.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ H. George Fletcher, In praise of Aldus Manutius (New York: Morgan Library, 1995), pp. 26–27.

- ↑ I. A. Carradice and T. V. Buttrey, The Imperial Roman Coinage: Volume II – Part 1; 2nd fully revised edition (London: Spink, 2007); see Titus nos. 110–114 and Domitian nos. 2, 12–13, 25–26, 51–55, and 96.

- ↑ Brian Richardson, Print Culture in Renaissance Italy: The Editor and the Vernacular Text (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 16.

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. p. 78. ISBN 9781606060834.

- ↑ Slobodan and Miodrag Nedeljkovic: Графичко обликовање и писмо

- ↑ Helen Barolini, Aldus and His Dream Book (New York: Italica Press, 1992), p. 84.

- ↑ The modern portable pocket book has become synonymous with the inexpensive paperback.

- ↑ Bembo's father Bernardo Bembo (1433–1519) was a distinguished Venetian patrician, a senator, and an ambassador for the Republic of Venice. Manutius' octavo format and its models in manuscripts of unglossed verses, is discussed by Nicolas Barker, Aldus Manutius and the Development of Greek Script & Type in the Fifteenth Century (Fordham University Press) 2nd ed. 1992, pp. 114ff.

- ↑ Truss 2004, p. 7.

- ↑ "Punctuation – Orthographiae ratio (work by Manutius)". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2014. Retrieved 2014-03-02. (subscription needed)

References

- Lyons, Martyn (2011), Books: A Living History (2nd ed.), Getty Publications, ISBN 9781606060834

- Truss, Lynn (2004), Eats, Shoot & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation, New York: Gotham Books, ISBN 1-59240-087-6

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Aldus Manutius". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Aldus Manutius". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Barker, N., Aldus Manutius and the Development of Greek Script and Type in the Fifteenth Century (2nd. ed., 1973)

- Barolini, Helen, Aldus and His Dream Book (New York: Italica Press, 1992)

- Braida, L., Stampa e Cultura in Europa (2003)

- Davies, Martin, Aldus Manutius, Printer and Publisher of Renaissance Venice (1995)

- Febvre, L. & Martin, H., La nascita del libro (2001. Roma-Bari: Laterza)

- Fletcher, H. G., New Aldine Studies: documentary essays on the life and work of Aldus Manutius (1988)

- Lowry, Martin J. C. (1979). The World of Aldus Manutius: Business and Scholarship in Renaissance Venice. Oxford: Blackwell. (Italian translation, Il Mondo di Aldo Manuzio (1984); 'con aggiornamento bibliografico', 2000)

- Norton, F. J., Italian Printers 1501–20 (1958)

- Nuovo, Angela (2016). "Aldo Manuzio a Los Angeles. La collezione Ahmanson-Murphy all'University of California Los Angeles". JLIS.it. 7 (1): 1–24. doi:10.4403/jlis.it-11426.

- Renouard, A. A., Annales de l'Imprimerie des Alde, ou L'Histoire des Trois Manuce et de leurs Editions (3me ed. 1834)

- Rives, Bruno, Aldo Manuzio, passions et secrets d'un venitien de genie (2008. Librii)

External links

Media related to Aldus Manutius at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Aldus Manutius at Wikimedia Commons- Exhibit on Aldus Manutius and his press at the Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University