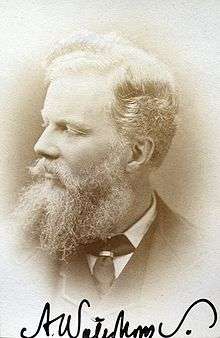

Alfred Waterhouse

| Alfred Waterhouse | |

|---|---|

Alfred Waterhouse | |

| Born |

19 July 1830 Aigburth, Liverpool, Lancashire, England |

| Died |

22 August 1905 (aged 75) Yattendon, Berkshire, England |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings |

Natural History Museum, London Manchester Town Hall Manchester Assize Courts Manchester Museum Clock Tower at Rochdale Town Hall |

Alfred Waterhouse RA (19 July 1830 – 22 August 1905) was an English architect, particularly associated with the Victorian Gothic Revival architecture. He is perhaps best known for his design for Manchester Town Hall and the Natural History Museum in London, although he also built a wide variety of other buildings throughout the country. Financially speaking, Waterhouse was probably the most successful of all Victorian architects. Though expert within Neo-Gothic, Renaissance revival and Romanesque revival styles, Waterhouse never limited himself to a single architectural style.

Early life

Waterhouse was born on 19 July 1830 in Aigburth, Liverpool, Lancashire, the son of wealthy mill-owning Quaker parents. His brothers were accountant Edwin Waterhouse, co-founder of the Price Waterhouse partnership that now forms part of PriceWaterhouseCoopers and solicitor Theodore Waterhouse, who founded the law firm Waterhouse & Co, now part of Field Fisher Waterhouse LLP in the City of London.[1][2]

Alfred Waterhouse was educated at the Quaker Grove House School in Tottenham. He studied architecture under Richard Lane in Manchester, and spent much of his youth travelling in Europe and studying in France, Italy and Germany. On his return to Britain, Alfred set up his own architectural practice in Manchester.[1]

Manchester practice

Waterhouse continued to practise in Manchester for 12 years, until moving his practice to London in 1865. His earliest commissions were for domestic buildings. In executing the commission for the cemetery buildings at Warrington Road, Lower Ince, (1855–56) he began his move towards designing public buildings in his developing Neo-Gothic style, building a lodge for the registrar, and two chapels, one Church of England, and one Non-conformist. His success as a designer of public buildings was assured in 1859 when he won the open competition for the Manchester Assize Courts (now demolished). This work not only showed his ability to plan a complicated building on a large scale, but also marked him out as a champion of the Gothic cause.[3]

In 1860, he married Elizabeth Hodgkin (1834–1918), daughter of John Hodgkin and sister of the historian Thomas Hodgkin. Elizabeth was herself the author of several books, including a collection of verse and some anthologies. Her best known work was The Island of Anarchy, a Utopian story set in the late 20th century, first published in 1887 and more recently re-published by the Reading-based Two Rivers Press.[4][5][6]

Waterhouse had connections with wealthy Quaker industrialist through schooling, marriage and religious affiliation. Many of these Quaker connections commissioned him to design and build country houses, especially in the areas near Darlington. Several were built for members of the Backhouse family, founders of Backhouse's Bank, a forerunner of Barclays Bank. For Alfred Backhouse, Waterhouse built Pilmore Hall (1863), now known as Rockliffe Hall, in Hurworth-on-Tees. In the same village he built the Grange (1875), now the Hurworth Grange Community Centre, which Alfred Backhouse had commissioned as a wedding gift for his nephew, James E. Backhouse. Another Backhouse family mansion designed and built by Waterhouse was Dryderdale Hall (1872), near Hamsterley, used for the home of Cyril Kinnear in the film Get Carter.[7]

London practice

In 1865, Waterhouse was one of the architects selected to compete for the Royal Courts of Justice. The University Club of New York was undertaken in 1866. In 1868 and nine years after his work on the Manchester Assize Courts, another competition secured for Waterhouse the design of Manchester Town Hall where he showed a firmer and more original handling of the Gothic style. The same year he was involved in rebuilding part of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge; this was not his first university work, for he had already worked on Balliol College, Oxford in 1867, and the new buildings of the Cambridge Union Society, in 1866.[3]

At Caius, out of deference to the Renaissance treatment of the older parts of the college, this Gothic element was intentionally mingled with classic detail, while Balliol and Pembroke College, Cambridge, which followed in 1871, are typical of the style of his mid career with Gothic tradition tempered by individual taste and by adaptation to modern needs. Girton College, Cambridge, a building of simpler type, dates originally from the same period (1870), but has been periodically enlarged by further buildings. Two important domestic works were undertaken in 1870 and 1871 respectively — Eaton Hall in Cheshire for the Duke of Westminster, and Heythrop Hall, Oxfordshire, the latter a restoration of a fairly strict classic type.[3]

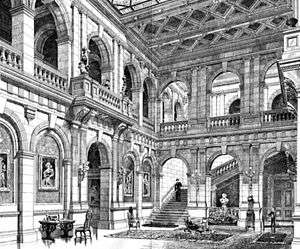

Waterhouse received, without competition, the commission to build the Natural History Museum in South Kensington (1873–1881), a design which marks an epoch in the modern use of architectural terracotta and which was to become his best known work. Waterhouse's other works in London included the National Liberal Club (a study in Renaissance composition), University College London's Cruciform Building, the former site of University College Hospital, the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors in London's Great George Street (1896), and the Jenner Institute of Preventive Medicine in Chelsea (1895).[3]

From the late 1860s, Waterhouse lived in Reading, Berkshire and was responsible for several significant buildings there. These included his own residences of Foxhill House (1868) and Yattendon Court (1877), together with Reading Town Hall (1875) and Reading School (1870). Foxhill House is still in use by the University of Reading, as are his Whiteknights House (built for his father) and East Thorpe House (built in 1880 for Alfred Palmer).[1]

For the Prudential Assurance Company, Waterhouse designed many offices, including their Holborn Bars head office in Holborn and branch offices in Southampton, Nottingham and Leeds. He also designed offices for the National Provincial Bank in Piccadilly (1892) and in Manchester. Liverpool Infirmary was Waterhouse's largest hospital; and St Mary's Hospital, Manchester, the Alexandra Hospital in Rhyl, and extensive additions at the Nottingham General Hospital, also involved him. He was involved in a series of works for the Victoria University of Manchester, of which he was made LL.D. in 1895.[3]

Other educational buildings designed by Waterhouse include High School, Middlesbrough (1875), Yorkshire College, Leeds (1878), the Victoria Building, Liverpool University (now University of Liverpool) (1885), St Paul's School in Hammersmith (1881-4; demolished 1968); and the Central Technical College in London's Exhibition Road (1881).[3]

Among works not already mentioned are the Cambridge Union building and subsequently a similar building for the Oxford Union; Strangeways Prison; St Margaret's School, Bushey; the Metropole Hotel in Brighton; Hove Town Hall; Knutsford Town Hall; Alloa Town Hall; St Elisabeth's Church, Reddish; Heaton Park Congregational Church in Prestwich; Darlington town clock, covered market hall and Backhouse's Bank (now Barclay's Bank); the former District Bank in Nantwich;[8] the King's Weigh House chapel in Mayfair; and Hutton Hall in Yorkshire (1866). St Mary's Church in Twyford, Hampshire (1878) shows interestingly similar patterning to the Natural History Museum and was designed at the same time.[3]

Later life

Waterhouse retired from architecture in 1902, having practised in partnership with his son, Paul Waterhouse, from 1891. He died at Yattendon Court on 22 August 1905.[1][3]

Recognition

Waterhouse became a fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1861, and was president from 1888 to 1891. He obtained a grand prix for architecture at the Paris Exposition of 1867, and a "Rappel" in 1878. In the same year he received the Royal Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and was made an associate of the Royal Academy, of which body he became a full member in 1885 and treasurer in 1898. He was also a member of the academies of Vienna (1869), Brussels (1886), Antwerp (1887), Milan (1888) and Berlin(1889), and a corresponding member of the Institut de France (1893). After 1886 he was constantly called upon to act as assessor in architectural competitions, and was a member of the international jury appointed to adjudicate on the designs for the west front of Milan Cathedral in 1887. In 1890 he served as architectural member of the Royal Commission on the proposed enlargement of Westminster Abbey as a place of burial.[3]

The JD Wetherspoon pub on Princess Street, Manchester, is named "The Waterhouse" after Alfred Waterhouse.[9]

List of architectural work

The names of the buildings and the names of the county they are located in, both in the lists and gallery, are those in use when Waterhouse designed the buildings.[10]

- List of ecclesiastical works by Alfred Waterhouse

- List of domestic works by Alfred Waterhouse

- List of educational buildings by Alfred Waterhouse

- List of commercial buildings by Alfred Waterhouse

- List of public and civic buildings by Alfred Waterhouse

Gallery of architectural work

-

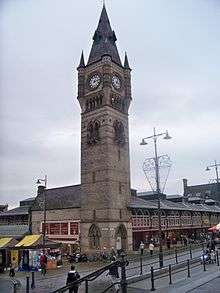

Darlington Market, County Durham (1861–64)

-

Strangeways Prison, Manchester (1861–69)

-

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1807.jpg)

Entrance, Strangeways Prison, Manchester (1861–69)

-

Former Manchester and Liverpool District Bank, Nantwich, Cheshire (1863–66)

-

Former Bassett and Harris Bank, Leighton Buzzard (1865–67)

-

The tower, Goldney House, Bristol, Gloucestershire (1865–68)

-

Easneye Park, Stanstead Abbots, Hertfordshire (1866)

-

Former North Western Hotel, Liverpool (1867)

-

Foxhill House, Reading (1867)

-

Foxhill House, Reading (1867)

-

.jpg)

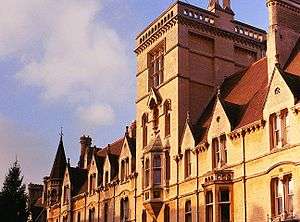

Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge (1867–76)

-

.jpg)

Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge (1867–76)

-

Reading School, Reading, Berkshire (1868–72)

-

Manchester Town Hall, from Albert Square (1868–77)

-

Clock tower, Manchester Town Hall (1868–77)

-

Manchester Town Hall, from Princess Street (1868–77)

-

Entrance front, Eaton Hall in 1907, Cheshire (1869–83) demolished apart from the chapel and stable court

-

Garden front, Eaton Hall in c.1880, Cheshire (1869–83) demolished apart from the chapel and stable court

-

The Chapel, Eaton Hall, Cheshire (1869–83)

-

Eaton Hall, with Waterhouse's chapel (1869–83) on the right

-

Golden Gates (1880), Eaton Hall, Cheshire (1869–83)

-

Natural History Museum, London (1870–80)

-

The main hall, Natural History Museum, London (1870–80)

-

The main hall, Natural History Museum, London (1870–80)

-

Windows, Natural History Museum, London (1870–80)

-

Detail of main hall, Natural History Museum, London (1870–80)

-

Pembroke College, Cambridge, Waterhouse's work on left (1870–73)

-

The Liverpool Seamen's Orphan Institution (1870–75)

-

The Liverpool Seamen's Orphan Institution (1870–75)

-

Market hall, Knutsford, Cheshire (1871–72)

-

The Saloon, Heythrop Hall, Oxfordshire (1871–72)

-

Municipal buildings, Reading, Berkshire (1871–76) & (1881)

-

The Chapel, Reading School, Reading, Berkshire (1873–74)

-

Pierremont clock tower, Darlington, County Durham (1873–75)

-

Balliol College. Oxford (1873–78)

-

Balliol College. Oxford (1873–78)

-

Girton College, Cambridge University (1875–77) &(1898–1902)

-

_20040228.png)

Oxford Union, Oxford University (1878–80)

-

Former East Thorpe House, Reading, Berkshire (1880–82)

-

Crimplesham Hall, Norfolk (1880–81)

-

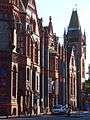

Owen's College, now Manchester University (1882–96)

-

St. Elizabeth's Church, Reddish, Stockport (1883–85)

-

New tower, Rochdale Town Hall (1885–88)

-

Prudential Assurance, Liverpool (1885–88)

-

Royal Infirmary, Liverpool (1886–92)

-

Royal Infirmary, Liverpool (1886–92)

-

National Liberal Club, London (1887)

-

Victoria Building, now Liverpool University (1888)

-

Former King's Weigh House Chapel, London (1889–93)

-

Former Refuge Assurance Building, Manchester (1891–96)

-

_022.jpg)

Baines Wing, Yorkshire College, now Leeds University (1892)

-

Exterior Great Hall, Yorkshire College, now Leeds University (1892)

-

Prudential Assurance, Nottingham (1893–98)

-

Prudential Assurance, Edinburgh (1895–96)

-

Former University College Hospital, London (1894–1903)

-

The main entrance, former University College Hospital, London (1894–1903)

-

Prudential Building, Holborn, London (1895–1905)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Royal Berkshire History — Alfred Waterhouse (1830–1905)". David Nash Ford. 2003. Archived from the original on 5 July 2005. Retrieved 2005-06-29.

- ↑ Waterhouse, Edwin (1988). Edgar Jones, ed. The Memoirs of Edwin Waterhouse. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-5579-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Waterhouse, Alfred". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Waterhouse, Alfred". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ "Natural History Museum Archive Catalogue - Alfred Waterhouse". Natural History Museum. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ↑ "Waterhouse Collection". University of Reading. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ↑ Waterhouse, Elizabeth. The Island of Anarchy. Two Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0952370185.

- ↑ "'Get Carter' mansion up for sale". BBC. 2008-04-01. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ↑ "District Bank, 1 and 3 Churchyard Side", Images of England, English Heritage, retrieved 23 June 2010

- ↑ "The Waterhouse". Manchester History. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ pages 207–275, Alfred Waterhouse 1830–1905 Biography of a Practice, Colin Cunningham & Prudence Waterhouse, 1992, Oxford University Press

External links

- Photograph of Backhouse Bank, High Row, Darlington

- Photograph of The Town Clock, Darlington

- Waterhouse images from the NHM picture library

- Waterhouse - the firm of architects still survives today

- St. Mary's Church, Twyford

- page=gr&GSln=waterhouse&GSfn=alfred&GSbyrel=all&GSdyrel=all&GScntry=5&GSob=n&GRid=21021919&df=all& His grave at Yattendon

- Profile on Royal Academy of Arts Collections